'Rage Against the Machist'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Platform Feminism: Feminist Protest Space and the Politics of Spatial Organization

Platform Feminism: Feminist Protest Space and the Politics of Spatial Organization by Rianka Singh A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Information University of Toronto © Copyright by Rianka Singh 2020 Platform Feminism: Feminist Protest Space and the Politics of Spatial Organization Rianka Singh Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Information University of Toronto 2020 Abstract Platform Feminism: Feminist Protest Space and the Politics of Spatial Organization examines the relationship between platforms and feminist politics. This dissertation proposes a new feminist media theory of the platform that positions the platform as a media object that elevates and amplifies some voices over others and renders marginal resistance tactics illegible. This dissertation develops the term “Platform Feminism” to describe an emerging view of digital platforms as always-already politically useful media for feminist empowerment. I argue that Platform Feminism has come to structure and dominate popular imaginaries of what a feminist politics is. In the same vein, the contemporary focus on digital platforms within media studies negates attention to the strategies of care, safety and survival that feminists who resist on the margins employ in the digital age. If we take seriously the imperative to survive rather than an overbearing commitment to speak up, then the platform’s role in feminism is revealed as limited in scope and potential. Through a mixed methodological approach via interviews with feminist activists, critical discourse analysis of platform protest materials, critical discourse analysis of news coverage and popular cultural responses to transnational feminist protests and participant observation within sites of feminist protest in Toronto, this dissertation argues that the platform is a media object that is over-determined in its political utility for Feminist politics and action. -

De /Constructing Internationalism

DE /CONSTRUCTING INTERNATIONALISM FEMINIST PRACTICES IN CONVERSATION DE /CONSTRUCTING INTERNATIONALISM FEMINIST PRACTICES IN CONVERSATION A FEMINIST INTERNATIONAL IN A MOMENT OF RADICAL OPENNESS As I write these lines, we are still in the midst of the global Corona pandemic whose consequences for our personal lives, our societies and international relations are still completely unresolved. On the one hand, the crisis and, in parti- cular, the governmental measures responding to it are aggravating pre-existing inequalities and oppression. Exposure to danger and access to support is determined by class, race and gender, as well as one’s position in the global economy. On the other hand, feminists continue to organize worldwide to make these problems visible and to increase the atten- tion currently paid to caring work and sustaining life and to use this for progressive initiatives. The contributions collected in this volume have emerged from a debate on feminist expectations of internationalism at the Feminist Futures Festival in September 2019 in Essen, Germany. That debate took place in a context in which feminist movements in different countries of the world were becoming increasingly loud and numerous and were also internationally connected to one other. Is this debate still relevant in the current situation? The answer is clearly yes. The contributions show that even in the past, of so-called normality, feminist struggles never took place without resis- tance and opposition, and yet movements and networks have developed that are no longer easily destroyed. That is why they continue to work even during this global pandemic. In these times, when the nation state is reappearing as it has not done for a long time and yet does not help many people, numerous feminist movements are exchanging experiences about local practices and are thus also giving impulses, inspiration and strength to more and more feminists. -

Chilean and Transnational Performances of Disobedience

Bulletin of Latin American Research, 2021 DOI:10.1111/blar.13215 Chilean and Transnational Performances of Disobedience: LasTesis and the Phenomenon of Un violador en tu camino DEBORAH MARTIN UCL, London, UK DEBORAH SHAW University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, UK This article analyses the performance Un violador en tu camino created by Chilean feminist theatre collective LasTesis, shared by millions and re-staged across the globe. It explores the relationship between the orig- inal piece and theorist Rita Segato’s insights on rape culture, and how it counters aspects of this culture. It examines how the transnational spread of Un violador counters tendencies of MeToo, and examines four cases of the performance’s re-staging in Latin America and beyond, showing how they make manifest the pervasiveness of rape culture as well as how groups have adapted them to speak to local issues. Keywords: activism, feminism, MeToo, protest, rape, Rita Laura Segato. On 20 November 2019, Chilean feminist theatre collective LasTesis staged a powerful street performance, Un violador en tu camino, in Valparaíso, calling out rape culture and indicting the state and wider society for women’s oppression. The performance went on to be shared and re-staged in Spanish-speaking countries including Argentina, Ecuador, Mexico, Paraguay, Spain, Nicaragua, Colombia, Peru, and Santo Domingo, and it has been reinterpreted in over 200 locations around the world (Cuffe, 2019). The original piece incorporates a powerful and catchy chant, references to Chilean national songs and accusations of rape against the instruments of the state, including the president. A dance routine recalls the humiliating poses women are required to adopt when detained by Chilean state forces, as well as utilising blindfolds and tight, stereotypically feminine clothing in a re-significatory way (Tesis, 2019). -

Social Protest Folklore and Student Critical Consciousness

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 22 Issue 1 Article 29 February 2021 Social Protest Folklore and Student Critical Consciousness Elise M. Brenner Bridgewater State University Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Brenner, Elise M. (2021). Social Protest Folklore and Student Critical Consciousness. Journal of International Women's Studies, 22(1), 504-522. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol22/iss1/29 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2021 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Social Protest Folklore and Student Critical Consciousness By Elise M. Brenner1 Abstract Bridgewater State University undergraduate Introduction to Folklore students, overwhelmingly young and white, with little to no experience with folklore, found a voice to honor and highlight liberatory and social justice-oriented protest folklore in and around the world and in their own experiences. Students in the fall 2020 Introduction to Folklore classes were confronted in life-altering ways with a global pandemic that endangered them and their loved ones and shone a light on hideous health inequities. The relentless killings of black people stripped away any illusions that systemic racism and white supremacy were not daily, ever- present forces. At the same time, Bridgewater State University was making purposeful and intentional efforts to being a social justice university. -

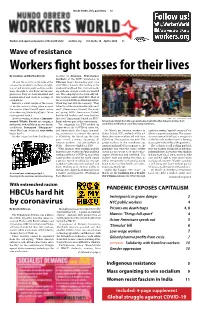

Workers Fight Bosses for Their Lives by Sue Davis and Martha Grevatt Months at Amazon

Desde dentro de la pandemia 12 Workers and oppressed peoples of the world unite! workers.org Vol. 62, No. 14 April 2, 2020 $1 Wave of resistance Workers fight bosses for their lives By Sue Davis and Martha Grevatt months at Amazon. Warehouse workers at the DCH1 warehouse in All over the country, in the wake of the Chicago began demanding paid time coronavirus pandemic, workers are fight- off (PTO) in January after reading in the ing for and winning safer working condi- employee handbook that everyone work- tions, the right to stay home and income ing 20 hours or more a week was entitled protection. They are both unionized and to it. The company tried to claim only full- nonunionized and work in a range of time workers could collect PTO. Most of occupations. the workers at DCH1 are Black and Latinx. Below is a small sample of the scores When they met with the company, “They of worker actions taking place around talked to us like stupid workers who can’t the country. (Read the full report online read.” (Amazonians United) The work- at workers.org/2020/03/47342/. More ers’ group, DCH1 Amazonians United, coverage next week.) distributed leaflets and wore buttons As we are writing, workers at Amazon- that read “Amazonians United for PTO.” CREDIT: DCH1 AMAZONIANS UNITED owned Whole Foods are waging a Strike talk was part of the conversation. Amazonians United from Chicago warehouse meet with other Amazon workers from nationwide sickout March 31 over unsafe The campaign for PTO picked up around the world before social distancing restrictions. -

2020 Abstracts

Abstracts for the Annual SECAC Conference Host Institution: Virginia Commonwealth University Convened Virtually November 30th - December 11th, 2020 Conference Chair: Carly Phinizy, Virginia Commonwealth University Hallie Abelman, University of Iowa The Home Lives of Animal Objects Ducks give pause to the DeafBlind poet John Lee Clark, who encounters them in rubber, stone, and wood while scanning aisles of gift shops and flea markets. Always perplexed by their flat bottoms, Clark notes how this perplexing design decision maintains visual (over tactile) privilege. The portal opened by this reflection exemplifies the precise intersection of animals, material culture, and disability driving Abelman’s performance-lecture at SECAC2020. Abelman treats each animal object she encounters as a prop and every mundane interaction with it as a performance, so Abelman demonstrates how the performativity of these obJects can elicit necessary humor, irony, and satire often missing from mainstream environmentalist narratives. Be they tchotchkes, souvenirs, commodities, or toys, each of these obJects has a culturally specific relationship to the species it portrays, a unique material makeup, and a history of being touched by human hands. Attending to the social construction of these realities aids an essential reconciliation between commodified animals and real animal livelihoods. Overall, the audience gains a better sense of how animal obJects can not only misrepresent a species but also contribute to that very species’s demise, be instrumentalized for the perpetuation of racist ideologies, and mobilize ableist fears. Rachel Allen, University of Delaware Nocturnes without Sky (World): FreDeric Remington Pushes Indigenous Cosmologies Out of the Frame This paper examines Frederic Remington’s (American, 1861–1909) The Gossips (1909) and the impact of his final paintings on Indigenous people and our cosmologies. -

Feminist Worldmaking and Musical Practice in Chile By

Resonance and Resistance: Feminist Worldmaking and Musical Practice in Chile by Christina Marie Azahar Folgar A dissertation in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Jocelyne Guilbault, Chair Professor T. Carlis Roberts Professor Charles L. Briggs Professor Daniel Party Spring 2021 Resonance and Resistance: Feminist Worldmaking and Musical Practice in Chile © 2021 by Christina Marie Azahar Folgar Abstract Resonance and Resistance: Feminist Worldmaking and Musical Practice in Chile by Christina Marie Azahar Folgar Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Jocelyne Guilbault, Chair This dissertation engages the concept of resonance in order to explore how Chilean feminist activists, musicians, industry leaders, and audiences have used popular musical practices to create space for themselves and their communities. Centrally, this study asks, how are feminist organizers in Chile engaging music to mobilize artists, audiences, and industries to end patterns of patriarchal oppression? To what extent do feminist musical practices allow participants to navigate, re-sound, and re-envision the physical, social, industrial, and virtual spaces of which they are a part? By examining a diversity of feminist musical practices from the mid-twentieth century to the present, I explain how musical and interpersonal resonances shape feminist coalition-building while also reconfiguring the gender politics of social and geophysical space. Each chapter in this dissertation makes audible distinct feminist understandings of Chilean music history, spatial politics, and the patriarchal systems that shape these. In Chapters Two and Three, I examine the role of cantautoras (women singer-songwriters) across generations of political movements, specifically addressing the feminist legacies, activism, and travels of folklorist Violeta Parra (b. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Dance in the Era of #Metoo THESIS Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for Th

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Dance in the Era of #MeToo THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS in Dance by Kiara Justine Kinghorn Thesis Committee: Professor Jennifer Fisher, Ph.D., Chair Professor Mary Corey Professor S. Ama Wray, Ph.D. 2020 © 2020 Kiara Justine Kinghorn DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to all the working women whose #MeToo story will never be heard because they are too busy cleaning your house or serving you food; And to anyone who is currently facing harassment and assault, or who is triggered by this work: It’s okay to log off. It’s okay to not participate. It’s okay. “I’ve only known for ten years that no is a full sentence.” —Jane Fonda ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv ABSTRACT OF THESIS: Dance in the Era of #MeToo v CHAPTER ONE: Volatility Introduction 1 #MeToo Ignites Online 3 #MeToo and Dance 4 Methods and Literature 6 CHAPTER TWO: Vulnerability Culture of Silence 10 Power Dynamics 14 Authoritarian Pedagogical Legacies 16 Outdated Patriarchal Systems 17 Echoes of Rape Culture in Dance 20 The “Disembodied Experience” of Dance Pedagogy 24 Touching 26 Consent 28 CHAPTER THREE: Visibility Whistle While You Work 32 Historical Perspectives on Putting the Body Back Together 34 Urban Bush Women 36 CHAPTER FOUR: Voice Choreographing a Dance Concert 38 The Three Fates 42 Nevertheless She Persisted 46 Beginning in the Middle 49 The Aggressor Solo 53 “A Rapist in Your Path” 54 iii Finishing in the Beginning 57 Harmful if Swallowed 59 Conclusion 59 WORKS CITED 62 APPENDIX : Concert Poster, Publicity Photos 66 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my Master of Fine Arts chair, Dr. -

THERE IS POWER in a PLAZA: SOCIAL MOVEMENTS, DEMOCRACY, and SPATIAL POLITICS by Kaitlin Kelly-Thompson

THERE IS POWER IN A PLAZA: SOCIAL MOVEMENTS, DEMOCRACY, AND SPATIAL POLITICS by Kaitlin Kelly-Thompson A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science West Lafayette, Indiana August 2020 THE PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL STATEMENT OF COMMITTEE APPROVAL Dr. S. Laurel Weldon, Chair Department of Political Science Dr. Valeria Sinclair-Chapman Department of Political Science Dr. Rachel L. Einwohner Department of Sociology Dr. Mary Scudder Department of Political Science Approved by: Dr. Cherie D. Maestas 2 For my sister, Stryker, for being my reason to try to make a better world, and for doing more than I ever could to get us there. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Just as cities can facilitate the development of inclusive social movements, my community provided both the material and intellectual support for me while I developed and wrote this dissertation. From the colleagues and mentors who pushed me to develop my theoretical framework to the friends and family who let me couch surf while conducting fieldwork, I could not have finished this without your support and solidarity. First and foremost, this dissertation would not have come into being without the support of my advisor S. Laurel Weldon. Your guidance led me to find my intellectual home, and your inspiring chaos has taught me to think big. Throughout this process, you have modelled the best kind of productive critique pushing both me and the project to become the best it could possibly be, while reminding me to not bury important findings with my own tendency to downplay the positives. -

International Annual Report 2019

International Annual Report 2019 Defending Freedom of Expression and Information around the World Economic inequalities continue to gape, discrimination continues unchecked, technology companies continue to hold extraordinary levels of power, and our environment continues to be degraded in the name of economic growth. Our need to know and understand, to refuse and to protest, are more urgent than ever – in this moment of history, the price of silence is higher than any of us can afford.” The Global Expression Report 2018/2019 Indigenous women take part in a protest against right-wing President Bolsonaro's environmental policies and the loss of their traditional settlements. Bolsonaro wants to make greater economic use of the Amazon region in particular and allow further deforestation. 13 August 2019, Brazil. (Photo: Tuane Fernandes/dpa) Contents Civic Space Digital Media Protection Transparency 6 From the Executive 30 #FreeToProtest 35 #SpeakingUp About Tech- 41 Social Media Councils: 47 Uniting for Protection: The 54 The World is Watching: Director: Quinn McKew /#LivreParaProtestar related VAW Protecting Freedom of Power of Coalitions Global Review of the RTI Expression in the “Online 7 From the Chair of 32 Unprecedented Progress 37 “Brazil’s GDPR” Finally 49 Solidarity with Journalists 55 Defending the Defenders in Public Square” the Board: Paddy on LGBTQI+ “Hate Speech” Passed in Turkey Latin America Coulter in Belarus 43 Media Plurality in Mexico 38 Punitive and Damaging: 50 “Offence Against Honour” 56 Kenya Sets a High Bar for 8 -

Celebrating 50 Years of Gender, Women & Sexuality Studies

PERSISTENCE IS RESISTANCE: CELEBRATING 50 YEARS OF GENDER, WOMEN & SEXUALITY STUDIES JULIE SHAYNE University of Washington libraries Seattle Persistence is Resistance: Celebrating 50 Years of Gender, Women & Sexuality Studies by Julie Shayne is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. As alAs always,ways, dedicated to my beloved father Barry (1945-2001) The night I received my MA in Women’s Studies. Photo taken before the San Francisco State University graduation. 1995. Contents Detailed contents, authors & artists included xiii Part I. Welcome Acknowledgements 3 About the cover 5 Preface: Context, Organization, and Non- 7 traditional publishing Introduction: Fifty Years of Women’s Studies 15 Part II. Section one: The History of Gender, Women, and Sexuality Studies 1. The History of San Diego State University’s 23 Women’s Studies Program Photos from SDSU library exhibit 37 2. The Praxis of Africana Women’s Studies: 39 Lessons from Clark Atlanta University 3. The Enduring Struggle: Findings from the 49 History of Women’s and Gender Studies in the Global South Untitled (student art) 62 4. Women’s-Gender-Sexuality-Feminist Studies: 64 The Politics of Departmental Naming 5. An Annotated Bibliography on the History of 72 Gender, Women, and Sexuality Studies in the Americas Untitled (student art) 89 Students answer: Why Gender, Women, and 91 Sexuality Studies? 6. Why GWSS Still Matters 93 Part III. Section two: The Praxis of Gender, Women, and Sexuality Studies 7. Bridging the Academy and the Community, 107 One Breath at a Time: The Healing Power of Africana Women’s Studies Students answer: Why Gender, Women, and 119 Sexuality Studies? 8. -

Political Journal of the Socialist Party Issue 11 Winter 2020 €3 / £3

S cialiSt Political Journal of the Socialist Party Issue 11 l Winter 2020 l €3 / £3 alternative trump DefeateD What Next? l Covid crisis exposes a rotten system – 10-point socialist programme l Global uprisings against oppression – socialist feminism now INSIDE l Engels @ 200 – a revolutionary thinker for a world in turmoil S cialiSt Political Journal of the Socialist Party Issue 11 l Winter 2020 alternative iN thiS iSSuE No.11 SOCIALIST ALTERNATIVE is the political and theoretical journal of the Socialist Party. FEaturE Editors: Kevin Henry, Eddie Covid Crisis Exposes A Rotten System McCabe, Conor Payne EDITORIAL 2 Design: Eddie McCabe Trump’s Out: Socialist Analysis & Next Steps SOCIALIST ALTERNATIVE (USA) 6 SubScribE Now! Get a subscription to Socialist Economic & Social Crisis of American Capitalism Alternative and The Socialist, the BY HARPER CLEVES 10 monthly newspaper of the Roots & Realities of Racism in Irish Society Socialist Party. Text “Subscribe” to 087 2400331 BY MYRIAM POIZAT & MANUS LENIHAN 12 Lessons & Legacy of the Debenhams Struggle coNtact thE BY MICHAEL O’BRIEN 16 SocialiSt party North: 07821058319 John Hume – A Critical Assessment South: 0873141986 BY DANIEL WALDRON 20 [email protected] Global Uprisings Against Oppression BY EMMA QUINN 24 iNtErNatioNal The Socialist Party is the Irish Friedrich Engels @ 200 – A Revolutionary Thinker section of International BY KATIA HANCKE 28 Socialist Alternative (ISA), a socialist organisation linking Engels, Marx & the ‘Irish Question’ together groups in over 30 BY KEVIN HENRY 34 countries. rEviEw internationalocialist.net carries reports of struggles, The Return of Nature by John Bellamy Foster analysis and a programme for REVIEWED BY KEISHIA TAYLOR 36 the fight against capitalism.