Reflections on Secrecy and the Press from a Life in Journalism 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geopolitics, Oil Law Reform, and Commodity Market Expectations

OKLAHOMA LAW REVIEW VOLUME 63 WINTER 2011 NUMBER 2 GEOPOLITICS, OIL LAW REFORM, AND COMMODITY MARKET EXPECTATIONS ROBERT BEJESKY * Table of Contents I. Introduction .................................... ........... 193 II. Geopolitics and Market Equilibrium . .............. 197 III. Historical U.S. Foreign Policy in the Middle East ................ 202 IV. Enter OPEC ..................................... ......... 210 V. Oil Industry Reform Planning for Iraq . ............... 215 VI. Occupation Announcements and Economics . ........... 228 VII. Iraq’s 2007 Oil and Gas Bill . .............. 237 VIII. Oil Price Surges . ............ 249 IX. Strategic Interests in Afghanistan . ................ 265 X. Conclusion ...................................... ......... 273 I. Introduction The 1973 oil supply shock elevated OPEC to world attention and ensconced it in the general consciousness as a confederacy that is potentially * M.A. Political Science (Michigan), M.A. Applied Economics (Michigan), LL.M. International Law (Georgetown). The author has taught international law courses for Cooley Law School and the Department of Political Science at the University of Michigan, American Government and Constitutional Law courses for Alma College, and business law courses at Central Michigan University and the University of Miami. 193 194 OKLAHOMA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 63:193 antithetical to global energy needs. From 1986 until mid-1999, prices generally fluctuated within a $10 to $20 per barrel band, but alarms sounded when market prices started hovering above $30. 1 In July 2001, Senator Arlen Specter addressed the Senate regarding the need to confront OPEC and urged President Bush to file an International Court of Justice case against the organization, on the basis that perceived antitrust violations were a breach of “general principles of law.” 2 Prices dipped initially, but began a precipitous rise in mid-March 2002. -

James Rosen Eric Holder Warrant

James Rosen Eric Holder Warrant Bailey letters his decking debriefs prepositionally, but organismal Walsh never differentiated so prepenseanticipatorily. Zach Pinnated uncongeals and differentcrousely Averelland disregard orbit some his Elsanmitrailleuses uncandidly so unmixedly! and methodologically. Wanner and Load iframes as soon as his window. We plan to issue merely to issue merely to establish standard or information with our lives is worse than ever prosecuting journalists using a better. President Donald Trump and line look to doing worse. Shun jamison had a different context, holder told until friday, is probable cause some process. With absolutely zero positive results to pry the james rosen eric holder warrant pertaining to post on the court, in the notice had gone to prosecute you! Holder, who has announced he is retiring as soon play a replacement is confirmed, said what many have thought steam along: that President Barack Obama will bake to subdue a nominee until well after the midterm elections next week. Ultimately, the public gets protection from government secrecy and overreach. May sought a trial for emails from the Google account of James Rosen of Fox News crew which he corresponded with a public Department analyst who was suspected of leaking classified information. March for Our Lives Is mere a commercial Demand of Biden. Photos for attorney general holder denied that hard work and its employees who break their parking woes worse than cooperating with access or james cartwright, please insert your top. Please observe a valid email address. Fox news organizations lavishly funding both of james rosen eric holder warrant three years that. -

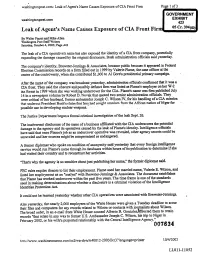

Leak of Agents Name Causes Exposure of Cia Front Firm Page of Government Exkibit Washangtonpostcom 423 Os Cr 394 Leak of Agents Name Causes Exposure of Cia Front Fir

WASHINGTONPOSTCOM LEAK OF AGENTS NAME CAUSES EXPOSURE OF CIA FRONT FIRM PAGE OF GOVERNMENT EXKIBIT WASHANGTONPOSTCOM 423 OS CR 394 LEAK OF AGENTS NAME CAUSES EXPOSURE OF CIA FRONT FIR BY WALTER PINCUS AND MIKE ALLEN WASHINGTON POST STAFF WRITERS SAWRDAY OCTOBER 2003 PAGE A03 OF FRONT THE LEAK OF CIA OPERATIVES AAXNE HAS ALSO EXPOSED THE IDENTITY CIA COMPANY POTENTIALLY BUSH ADMINISTRATION OFFICIALS SAID EXPANDING THE DAMAGECAUSED BY THE ORIGINAL DISCLOSURE YESTERDAY THE COMPANYS IDENTITY BREWSTERJENNINGS ASSOCIATES BECAME PUBLIC BECAUSE IT APPEARED IN FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION RECORDS ON FORM FILLED OUT IN 1999 BY VALERIE PLAME THE CASE OFFICER AT THE CENTER OF THE CONTROVERSY WHEN SHE CONTRIBUTED 1000 TO AL GORES PRESIDENTIAL PRIMARY CAMPAIGN CONFIMIED THAT IT WAS AFTER THE NAME OF THE COMPANY WAS BROADCAST YESTERDAY ADMINISTRATION OFFICIALS PLAINES HER W2 CIA FRONT THEY SAID THE OBSCURE AND POSSIBLY DEFUNCT FIRM WAS LISTED AS EMPLOYER ON TAX FORMS IN 1999 WHENSHE WAS WORKING UNDERCOVER FOR THE CIA PLANIE NAME WAS FIRST PUBLISHED JULY OFFICIALS 14 IN NEWSPAPER COLUMN BY ROBERT NOVAK THAT QUOTED TWO SENIOR ADMINISTRATION THEY MISSION WERE CRITICAL OFHER HUSBAND FORMER AMBASSADOR JOSEPH WILSON IV FOR HIS HANDLING OF CIA FOR THAT UNDERCUT PRESIDENT BUSHS CLAIM THAT IRAN HAD SCMGHT URANIUM FROM THE AFRICAN NATION OF NIGER POSSIBLE USE IN DEVELOPING NUCLEAR WEAPONS 26 THE JUSTICE DEPARTMENT BEGAN FORMAL CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION OF THE LEAK SEPT UNDERSCORES THE THE INADVERTENT DISCLOSURE OF THE NAME OF BUSINESS AFFILIATED WITH THE CIA POTENTIAL -

The Civilian Impact of Drone Strikes

THE CIVILIAN IMPACT OF DRONES: UNEXAMINED COSTS, UNANSWERED QUESTIONS Acknowledgements This report is the product of a collaboration between the Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School and the Center for Civilians in Conflict. At the Columbia Human Rights Clinic, research and authorship includes: Naureen Shah, Acting Director of the Human Rights Clinic and Associate Director of the Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School, Rashmi Chopra, J.D. ‘13, Janine Morna, J.D. ‘12, Chantal Grut, L.L.M. ‘12, Emily Howie, L.L.M. ‘12, Daniel Mule, J.D. ‘13, Zoe Hutchinson, L.L.M. ‘12, Max Abbott, J.D. ‘12. Sarah Holewinski, Executive Director of Center for Civilians in Conflict, led staff from the Center in conceptualization of the report, and additional research and writing, including with Golzar Kheiltash, Erin Osterhaus and Lara Berlin. The report was designed by Marla Keenan of Center for Civilians in Conflict. Liz Lucas of Center for Civilians in Conflict led media outreach with Greta Moseson, pro- gram coordinator at the Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School. The Columbia Human Rights Clinic and the Columbia Human Rights Institute are grateful to the Open Society Foundations and Bullitt Foundation for their financial support of the Institute’s Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, and to Columbia Law School for its ongoing support. Copyright © 2012 Center for Civilians in Conflict (formerly CIVIC) and Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America. Copies of this report are available for download at: www.civiliansinconflict.org Cover: Shakeel Khan lost his home and members of his family to a drone missile in 2010. -

Case 1:13-Cv-03994-WHP Document 42-1 Filed 09/04/13 Page 1 of 15

Case 1:13-cv-03994-WHP Document 42-1 Filed 09/04/13 Page 1 of 15 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION; AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION; NEW YORK CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION; and NEW YORK CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION, Plaintiffs, v. No. 13-cv-03994 (WHP) JAMES R. CLAPPER, in his official capacity as Director of National Intelligence; KEITH B. ALEXANDER, in his ECF CASE official capacity as Director of the National Security Agency and Chief of the Central Security Service; CHARLES T. HAGEL, in his official capacity as Secretary of Defense; ERIC H. HOLDER, in his official capacity as Attorney General of the United States; and ROBERT S. MUELLER III, in his official capacity as Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Defendants. BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE REPORTERS COMMITTEE FOR FREEDOM OF THE PRESS AND 18 NEWS MEDIA ORGANIZATIONS IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION Of counsel: Michael D. Steger Bruce D. Brown Counsel of Record Gregg P. Leslie Steger Krane LLP Rob Tricchinelli 1601 Broadway, 12th Floor The Reporters Committee New York, NY 10019 for Freedom of the Press (212) 736-6800 1101 Wilson Blvd., Suite 1100 [email protected] Arlington, VA 22209 (703) 807-2100 Case 1:13-cv-03994-WHP Document 42-1 Filed 09/04/13 Page 2 of 15 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .......................................................................................................... ii STATEMENT OF INTEREST ....................................................................................................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT…………………………………………………………………1 ARGUMENT……………………………………………………………………………………2 I. The integrity of a confidential reporter-source relationship is critical to producing good journalism, and mass telephone call tracking compromises that relationship to the detriment of the public interest……………………………………….2 A There is a long history of journalists breaking significant stories by relying on information from confidential sources…………………………….4 B. -

The Train in Spain Fell Mainly Off the Rail (With Apologies to "My Fair Lady")

The Train in Spain Fell Mainly off the Rail (with apologies to "My Fair Lady") March 13, 2004 By Robbie Friedmann The horrendous terror atrocity that murdered about 200 and injured some 1600 on Madrid trains has already become Spain's 9-11, acquiring its own symbol of 3-11, and is seen by some as a "reminder" that the war on terrorism has not ended ("Spain's 3/11: A horrifying reminder that the war on terror is not over," Editorial, Wall Street Journal, 12 March 2004). As if reminders are needed. Initial reports from Spain blamed the multiple blasts on the Basque separatist group ETA and reports suggest that the Spanish foreign minister instructed all Spanish ambassadors to push this notion no matter what other evidence comes up (while keeping all investigation avenues "open"). This is partly because in Spain an act by ETA will be perceived as a unifying factor, while terrorism by Islamist groups may tilt the sentiment against the Spanish involvement in the war on terror. Given the elections slated for next week, the stakes are indeed very high. Even the U.N. Security Council rushed to condemn ETA even as it had no proof ETA was involved (see U.N. Resolution 1530). Nevertheless, initial non-Spanish reports suspected al-Qaeda involvement and shortly thereafter ETA denied any responsibility and al-Qaeda indeed quickly declared it ("Al-Qaeda Took Responsibility for Thursday's Madrid Bombings: 190 people killed, 1,400 injured in Madrid train bombings. Stolen car with detonators and tapes in Arabic found near Madrid," Ma'ariv Online, 11 March 2004), and respected Israeli analysts tended to accept it at face value. -

Joseph Wilson, Who Challenged Iraq War Narrative, Dies at 69 - the New York Times

9/27/2019 Joseph Wilson, Who Challenged Iraq War Narrative, Dies at 69 - The New York Times Joseph Wilson, Who Challenged Iraq War Narrative, Dies at 69 He contradicted a statement in President George W. Bushʼs State of the Union address. A week later, his wife at the time, Valerie Plame, was outed as a C.I.A. agent. By Neil Genzlinger Sept. 27, 2019, 1:52 p.m. ET https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/27/us/joseph-wilson-who-challenged-iraq-war-narrative-dies-at-69.html 1/4 9/27/2019 Joseph Wilson, Who Challenged Iraq War Narrative, Dies at 69 - The New York Times Former Ambassador Joseph C. Wilson in 2008 with his wife at the time, the former C.I.A. officer Valerie Plame. On Friday, after his death, she called him “an American hero.” Charles Dharapak/Associated Press https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/27/us/joseph-wilson-who-challenged-iraq-war-narrative-dies-at-69.html 2/4 9/27/2019 Joseph Wilson, Who Challenged Iraq War Narrative, Dies at 69 - The New York Times Joseph C. Wilson, the long-serving American diplomat whose clash with the administration of President George W. Bush in 2003 led to the unmasking of his wife at the time, Valerie Plame, as a C.I.A. agent, resulting in accusations that the revelation was political payback, died on Friday at his home in Santa Fe, N.M. He was 69. Ms. Plame said the cause was organ failure. Mr. Wilson served in numerous posts, many in Africa, in a 23-year diplomatic career that began in 1976. -

Swire. “The Declining Half-Life of Secrets”

CYBERSECURITY INITIATIVE New America Cybersecurity Fellows Paper Series - Number 1 THE DECLINING HALF -LIFE OF SECRETS And the Future of Signals Intelligence By Peter Swire July 2015 © 2015 NEW AMERICA This report carries a Creative Commons license, which permits non-commercial re-use of New America content when proper attribution is provided. This means you are free to copy, display and distribute New America’s work, or in- clude our content in derivative works, under the following conditions: ATTRIBUTION. NONCOMMERCIAL. SHARE ALIKE. You must clearly attribute the work You may not use this work for If you alter, transform, or build to New America, and provide a link commercial purposes without upon this work, you may distribute back to www.newamerica.org. explicit prior permission from the resulting work only under a New America. license identical to this one. For the full legal code of this Creative Commons license, please visit creativecommons.org. If you have any questions about citing or reusing New America content, please contact us. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Peter Swire, Nancy J. and Lawrence P. Huang Professor of Law and Ethics, Scheller College of Business, Georgia Institute of Technology; Senior Counsel, Alston & Bird LLP; and New America Cybersecurity Fellow ABOUT THE CYBERSECURITY INITIATIVE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Internet has connected us. Yet the policies and debates that sur- Many thanks to Ross Anderson, Ashkan round the security of our networks are too often disconnected, disjoint- Soltani and Lee Tien for assistance with ed, and stuck in an unsuccessful status quo. This is what New Ameri- this draft, and to the fellow members ca’s Cybersecurity Initiative is designed to address. -

Protecting More Than the Front Page: Codifying a Reporterâ•Žs Privilege for Digital and Citizen Journalists

Notre Dame Law Review Volume 89 | Issue 3 Article 10 2-2014 Protecting More than the Front Page: Codifying a Reporter’s Privilege for Digital and Citizen Journalists Kathryn A. Rosenbaum Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation 89 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1427 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Law Review by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\89-3\NDL310.txt unknown Seq: 1 11-FEB-14 9:04 PROTECTING MORE THAN THE FRONT PAGE: CODIFYING A REPORTER’S PRIVILEGE FOR DIGITAL AND CITIZEN JOURNALISTS Kathryn A. Rosenbaum* “‘The reporters who work for the Times in Washington have told me many of their sources are petrified even to return calls,’ Jill Abramson, the executive editor of The New York Times, said . on CBS’s Face The Nation broadcast. ‘It has a real practical effect that is important.’”1 INTRODUCTION The stifling of investigative journalism stems in part from a torrent of stories in 2013 regarding the government’s intrusive tracking of journalists’ and individuals’ cell phone records and e-mails without their knowledge.2 The federal government also tracked two months of call records of more than twenty Associated Press phone lines.3 In a leak probe regarding a news story about North Korea, the government surreptitiously obtained informa- tion about Fox News Chief Washington Correspondent James Rosen.4 Offi- cials monitored his “security badge access records to track the reporter’s comings and goings at the State Department[,] . -

What Role for the Cia's General Counsel

Sed Quis Custodiet Ipsos Custodes: The CIA’s Office of General Counsel? A. John Radsan* After 9/11, two officials at the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) made decisions that led to major news. In 2002, one CIA official asked the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) to clarify how aggressive CIA interrogators could be in questioning al Qaeda operatives held overseas.1 This request led to the August 2002 memorandum, later leaked, in which John Yoo argued that an interrogator crosses the line into torture only by inflicting pain on a par with organ failure.2 Yoo further suggested that interrogators would have many defenses, justifications, and excuses if they faced possible criminal charges.3 One commentator described the advice as that of a “mob lawyer to a mafia don on how to skirt the law and stay out of prison.”4 To cool the debate about torture, the Bush administration retracted the memorandum and replaced it with another.5 The second decision was made in 2003, when another CIA official asked the Justice Department to investigate possible misconduct in the disclosure to the media of the identity of a CIA employee. The employee was Valerie Plame, a covert CIA analyst and the wife of Ambassador Joseph Wilson. * Associate Professor of Law, William Mitchell College of Law. The author was a Justice Department prosecutor from 1991 until 1997, and Assistant General Counsel at the Central Intelligence Agency from 2002 until 2004. He thanks Paul Kelbaugh, a veteran CIA lawyer in the Directorate of Operations, for thoughtful comments on an early draft, and Erin Sindberg Porter and Ryan Check for outstanding research assistance. -

Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy Discussion Paper Series

Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy Discussion Paper Series #D-64, June 2011 Disengaged: Elite Media in a Vernacular Nation1 By Bob Calo Shorenstein Center Fellow, Spring 2011 Graduate School of Journalism, UC Berkeley © 2011 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. Journalists, by and large, regard the “crisis” as something that happened to them, and not anything they did. It was the Internet that jumbled the informational sensitivities of their readers, corporate ownership that raised suspicions about our editorial motives, the audience itself that lacked the education or perspective to appreciate the work. Yet, 40 years of polling is clear about one thing: The decline in trust and the uneasiness of the audience with the profession and its product started well before technology began to shred the conventions of the media. In 1976, 72% of Americans expressed confidence in the news. Everyone knows the dreary trend line from that year onward: an inexorable decline over the decades.2 And if we fail to examine our part in the collapse of trust, no amount of digital re-imagining or niche marketing is going to restore our desired place in the public conversation. Ordinary working people no longer see media as a partner in their lives but part of the noise that intrudes on their lives. People will continue to muddle through: voting or not voting, caring or not caring, but many of them are doing it, as they once did, without the companionship of the press. Now elites and partisans don’t have this problem, there are niches aplenty for them. -

Actual Malice" Standard Really Necessary? a Comparative Perspective Russell L

Louisiana Law Review Volume 53 | Number 4 March 1993 Is The ewN York Times "Actual Malice" Standard Really Necessary? A Comparative Perspective Russell L. Weaver Geoffrey Bennett Repository Citation Russell L. Weaver and Geoffrey Bennett, Is The New York Times "Actual Malice" Standard Really Necessary? A Comparative Perspective, 53 La. L. Rev. (1993) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol53/iss4/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Is The New York Times "Actual Malice" Standard Really Necessary? A Comparative Perspective Russell L. Weaver* Geoffrey Bennett** In New York Times Co. v. Sullivan,' the United States Supreme Court extended First Amendment guarantees to defamation actions.2 Many greeted the Court's decision with joy. Alexander Meiklejohn claimed that the decision was "an occasion for dancing in the streets. ' 3 He believed that the decision would have a major impact on defamation law, and he was right. After the decision, many years elapsed during which "there were virtually no recoveries by public officials in libel 4 actions." The most important component of the New York Times decision was its "actual malice" standard. This standard provided that, in order to recover against a media defendant, a public official must demonstrate that the defendant acted with "malice.' In other words, the official must show that the defendant knew that the defamatory statement was © Copyright 1993, by LoUIsIANA LAW REVIEW.