Perception and Complicity in Octavia Butler's Kindred and J.M. Coetzee's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Mexico New Mexico

NEW MEXICO NEWand MEXICO the PIMERIA ALTA THE COLONIAL PERIOD IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEst edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves NEW MEXICO AND THE PIMERÍA ALTA NEWand MEXICO thePI MERÍA ALTA THE COLONIAL PERIOD IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEst edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO Boulder © 2017 by University Press of Colorado Published by University Press of Colorado 5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C Boulder, Colorado 80303 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of Association of American University Presses. The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University. ∞ This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). ISBN: 978-1-60732-573-4 (cloth) ISBN: 978-1-60732-574-1 (ebook) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Douglass, John G., 1968– editor. | Graves, William M., editor. Title: New Mexico and the Pimería Alta : the colonial period in the American Southwest / edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves. Description: Boulder : University Press of Colorado, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016044391| ISBN 9781607325734 (cloth) | ISBN 9781607325741 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Spaniards—Pimería Alta (Mexico and Ariz.)—History. | Spaniards—Southwest, New—History. | Indians of North America—First contact with Europeans—Pimería Alta (Mexico and Ariz.)—History. -

Vaclav Havel's “The Power of the Powerless”

Vaclav Havel’s “The Power of the Powerless” "The Power of the Powerless" (October 1978) was originally written as a discussion piece for a projected joint Polish Czechoslovak volume of essays on the subject of freedom and power. All the participants were to receive Havel's essay, and then respond to it in writing. Twenty participants were chosen on both sides, but only the Czechoslovak side was completed. Meanwhile, in May 1979, some of the Czechoslovak contributors, including Havel, were arrested, and it was decided to go ahead and "publish" the Czechoslovak contributions separately. Havel's essay has had a profound impact on Eastern Europe. Zbygniew Bujak, a Solidarity activist, said: "This essay reached us in the Ursus factory in 1979 at a point when we felt we were at the end of the road. Inspired by KOR [the Polish Workers' Defense Committee], we had been speaking on the shop floor, talking to people, participating in public meetings, trying to speak the truth about the factory, the country, and politics. There came a moment when people thought we were crazy. Why were we doing this? Why were we taking such risks? Not seeing any immediate and tangible results, we began to doubt the purposefulness of what we were doing. Shouldn’t we be coming up with other methods, other ways? Then came the essay by Havel. Reading it gave us the theoretical underpinnings for our activity. It maintained our spirits; we did not give up, and a year later - in August 1980 - it became clear that the party apparatus and the factory management were afraid of us. -

Father Heinrich As Kindred Spirit

father heinrich as kindred spirit or, how the log-house composer of kentucky became the beethoven of america betty e. chmaj Thine eyes shall see the light of distant skies: Yet, COLE! thy heart shall bear to Europe's strand A living image of their own bright land Such as on thy glorious canvas lies. Lone lakes—savannahs where the bison roves— Rocks rich with summer garlands—solemn streams— Skies where the desert eagle wheels and screams— Spring bloom and autumn blaze of boundless groves. Fair scenes shall greet thee where thou goest—fair But different—everywhere the trace of men. Paths, homes, graves, ruins, from the lowest glen To where life shrinks from the fierce Alpine air, Gaze on them, till the tears shall dim thy sight, But keep that earlier, wilder image bright. —William Cullen Bryant, "To Cole, the Painter, Departing for Europe" (1829) More than any other single painting, Asher B. Durand's Kindred Spirits of 1849 has come to speak for mid-nineteenth-century America (Figure 1). FIGURE ONE (above): Asher B. Durand, Kindred Spirits (1849). The painter Thomas Cole and the poet William Cullen Bryant are shown worshipping wild American Nature together from a precipice high in the CatskiJI Mountains. Reprinted by permission of the New York Public Library. 0026-3079/83/2402-0035$0l .50/0 35 The work portrays three kinds of kinship: the American's kinship with Nature, the kinship of painting and poetry, and the kinship of both with "the wilder images" of specifically American landscapes. Commissioned by a patron at the time of Thomas Cole's death as a token of gratitude to William Cullen Bryant for his eulogy at Cole's funeral, the work shows Cole and Bryant admiring together the kind of images both had commem orated in their art. -

Gender, Ritual and Social Formation in West Papua

Gender, ritual Pouwer Jan and social formation Gender, ritual in West Papua and social formation A configurational analysis comparing Kamoro and Asmat Gender,in West Papua ritual and social Gender, ritual and social formation in West Papua in West ritual and social formation Gender, This study, based on a lifelong involvement with New Guinea, compares the formation in West Papua culture of the Kamoro (18,000 people) with that of their eastern neighbours, the Asmat (40,000), both living on the south coast of West Papua, Indonesia. The comparison, showing substantial differences as well as striking similarities, contributes to a deeper understanding of both cultures. Part I looks at Kamoro society and culture through the window of its ritual cycle, framed by gender. Part II widens the view, offering in a comparative fashion a more detailed analysis of the socio-political and cosmo-mythological setting of the Kamoro and the Asmat rituals. These are closely linked with their social formations: matrilineally oriented for the Kamoro, patrilineally for the Asmat. Next is a systematic comparison of the rituals. Kamoro culture revolves around cosmological connections, ritual and play, whereas the Asmat central focus is on warfare and headhunting. Because of this difference in cultural orientation, similar, even identical, ritual acts and myths differ in meaning. The comparison includes a cross-cultural, structural analysis of relevant myths. This publication is of interest to scholars and students in Oceanic studies and those drawn to the comparative study of cultures. Jan Pouwer (1924) started his career as a government anthropologist in West New Guinea in the 1950s and 1960s, with periods of intensive fieldwork, in particular among the Kamoro. -

A Retrospective of Sculpture by CLOSE PROXIMITY: Neil Goodman

PRESENTS CLOSE PROXIMITY: A Retrospective of Sculpture by Neil Goodman Contents Introduction ............................. 10 Foreword ..................................19 Artist’s Statement ..................... 33 PRESENTS Interview ................................. 38 Neil Goodman Biography .......... 48 CLOSE PROXIMITY: Artwork Plates ......................... 50 A Retrospective of Sculpture by Founded in 1981 with the mission of “making art a part of everyday life”, the Museum of Outdoor Arts (MOA) is a forerunner in the placement of site-specific sculpture in Colorado. Our art collection is located at public locations throughout the Denver metro area. From commercial office parks to botanic gardens, city parks and traditional sculpture gardens; art is placed to interpret space as Neil Goodman “a museum without walls.” MOA also curates indoor galleries and hosts world-class art exhibitions and educational programs. Please visit our website to learn more about MOA. MOAonline.org MOA INDOOR GALLERY Follow Us @OutdoorArts 1000 Englewood Parkway, Second Floor, Englewood, CO 80110 Exhibiting September 15 – November 17, 2018 OUTDOOR INSTALLATION AT WESTLANDS PARK All photography by 5701 South Quebec Street, Greenwood Village, CO 80111 Heather Longway Exhibiting September 2018 – August 2019 2 CLOSE PROXIMITY: A Retrospective of Sculpture by Neil Goodman MOA, September 15 - November 17, 2018 3 4 CLOSE PROXIMITY: A Retrospective of Sculpture by Neil Goodman MOA, September 15 - November 17, 2018 5 6 CLOSE PROXIMITY: A Retrospective of Sculpture by Neil Goodman MOA, September 15 - November 17, 2018 7 8 CLOSE PROXIMITY: A Retrospective of Sculpture by Neil Goodman MOA, September 15 - November 17, 2018 9 INTRODUCTION retrospective exhibition. We all became fast the massive sculptures frame the landscape. friends and enthusiastic collaborators. -

Revised for Release Feb. 19, 2016 Media Contact: Laura Carpenter

625 C Street, Anchorage AK 99501 Revised for release Feb. 19, 2016 Media Contact: Laura Carpenter, (907) 929-9227, [email protected] SCHEDULE OF PROGRAMS AND EXHIBITIONS MARCH/APRIL 2016 *EDITORS PLEASE NOTE: This release replaces previous schedules. Download related media images at www.anchoragemuseum.org/media. Information provided below is subject to change. To confirm details and dates, call the Marketing and Public Relations Department at (907) 929-9227. News page 1 March Events page 2 April Events page 5 Planetarium page 6 Classes and Workshops page 8 Upcoming Exhibitions page 9 Current Exhibitions page 10 Partner Programs page 11 Visitor Information page 12 NEWS Artists invited to apply for exhibitions at the Anchorage Museum The Anchorage Museum is accepting submissions until March 10 for project proposals for solo and group exhibitions. The Anchorage Museum’s Patricia B. Wolf Solo Exhibition Series supports the work and development of Alaska artists, highlighting new bodies of work by individual artists. Alaska artists are invited to submit applications to a selection committee comprised of museum staff and art professionals. These solo art exhibitions will be scheduled starting in 2017. The Anchorage Museum is currently accepting proposals from Alaska residents and all tribally enrolled Alaska Natives. Works in all media will be considered. The Anchorage Museum is also accepting curatorial and group proposals featuring more than one artist. These proposals will not be part of the Patricia B. Wolf exhibition series but will be brought before the museum’s Exhibition Review Committee for consideration. Applicants for group and curatorial proposals do not need to be from Alaska, but successful proposals will support the museum’s mission to connect people, expand perspectives and encourage global dialogue about the North and its distinct environment. -

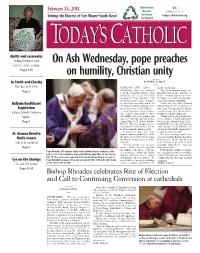

On Ash Wednesday, Pope Preaches on Humility, Christian Unity

February 24, 2013 Think Green 50¢ Recycle Volume 87, No. 8 Go Green todayscatholicnews.org Serving the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend Go Digital TTODAYODAY’’SS CCATHOLICATHOLIC Quilts and casseroles Finding fulfillment with On Ash Wednesday, pope preaches interests, service to others Pages 8-10 on humility, Christian unity In Truth and Charity BY FRANCIS X. ROCCA The Chair of St. Peter VATICAN CITY (CNS) — ing the vast basilica. Page 2 Celebrating what was expected The Ash Wednesday liturgy, tra- to be the last public liturgy of his ditionally held in two churches on pontificate two weeks before his Rome’s Aventine Hill, was moved to resignation, Pope Benedict XVI St. Peter’s to accommodate the great- preached on the virtues of humil- est possible number of faithful. Indiana healthcare ity and Christian unity and heard At the end of the Mass, Cardinal his highest-ranking aide pay trib- Tarcisio Bertone, who as secretary of legislation ute to his service to the Church. state is the Vatican’s highest official, Jesus “denounces religious hypoc- voiced gratitude for Pope Benedict’s Indiana Catholic Conference risy, behavior that wants to show pontificate of nearly eight years. update off, attitudes that seek applause and “Thank you for giving us the lumi- approval,” the pope said in his homily nous example of a simple and humble Page 5 during Mass in St. Peter’s Basilica laborer in the vineyard of the Lord,” Feb. 13. “The true disciple does not Cardinal Bertone said, invoking the serve himself or the ‘public,’ but his same metaphor Pope Benedict had Lord, in simplicity and generosity.” used in his first public statement fol- Coming two days after Pope lowing his election in 2005. -

Myth, the Marvelous, the Exotic, and the Hero in the Roman D'alexandre

Myth, the Marvelous, the Exotic, and the Hero in the Roman d’Alexandre Paul Henri Rogers A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Languages (French) Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: Dr. Edward D. Montgomery Dr. Frank A. Domínguez Dr. Edward D. Kennedy Dr. Hassan Melehy Dr. Monica P. Rector © 2008 Paul Henri Rogers ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract Paul Henri Rogers Myth, the Marvelous, the Exotic, and the Hero in the Roman d’Alexandre Under the direction of Dr. Edward D. Montgomery In the Roman d’Alexandre , Alexandre de Paris generates new myth by depicting Alexander the Great as willfully seeking to inscribe himself and his deeds within the extant mythical tradition, and as deliberately rivaling the divine authority. The contemporary literary tradition based on Quintus Curtius’s Gesta Alexandri Magni of which Alexandre de Paris may have been aware eliminates many of the marvelous episodes of the king’s life but focuses instead on Alexander’s conquests and drive to compete with the gods’ accomplishments. The depiction of his premature death within this work and the Roman raises the question of whether or not an individual can actively seek deification. Heroic figures are at the origin of divinity and myth, and the Roman d’Alexandre portrays Alexander as an essentially very human character who is nevertheless dispossessed of the powerful attributes normally associated with heroic protagonists. -

Frank O'hara's Oranges : Poetry, Painters and Painting

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-2001 Frank O'Hara's oranges : poetry, painters and painting. Karen Ware 1973- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ware, Karen 1973-, "Frank O'Hara's oranges : poetry, painters and painting." (2001). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1531. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1531 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FRANK O'HARA'S ORANGES: Poetry, Painters and Painting By Karen Ware B.A., Spalding University, 1994 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Department of English University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky August 2001 FRANK O'HARA'S ORANGES: Poetry, Painters and Painting By Karen Ware B.A., Spalding University, 1994 A Thesis Approved on by the following Reading Committee: Thesis MrectO'r 11 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to Clare Pearce, because I promised, and to Kyle, through all things. III ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many amazing individuals have taken a seat in the roller coaster construction of this long-awaited project. -

Alien Love- Passing, Race, and the Ethics of the Neighbor in Postwar

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Alien Love: Passing, Race, and the Ethics of the Neighbor in Postwar African American Novels, 1945-1956 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy In English By Hannah Wonkyung Nahm 2021 © Copyright by Hannah Wonkyung Nahm 2021 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Alien Love: Passing, Race, and the Ethics of the Neighbor in Postwar African American Novels, 1945-1956 by Hannah Wonkyung Nahm Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2021 Professor King-Kok Cheung, Co-Chair Professor Richard Yarborough, Co-Chair This dissertation examines Black-authored novels featuring White (or White-passing) protagonists in the post-World War II decade (1945-1956). Published during the fraught postwar political climate of agitation for integration and the continual systematic racism, many novels by Black authors addressed the urgent topic of interracial relationality, probing the tabooed question of whether Black and White can abide in love and kinship. One of the prominent—and controversial—literary strategies sundry Black novelists used in this decade was casting seemingly raceless or ambiguously-raced characters. Collectively, these novels generated a mixture of critical approval and dismissal in their time and up until recently, marginalized from the African American literary tradition. Even more critically overlooked than the ostensibly raceless project was the strategic mobilization of the trope of passing by some midcentury Black ii writers to imagine the racial divide and possible reconciliation. This dissertation intersects passing with postwar Black fiction that features either racially-anomalous or biracial central characters. Examining three novels from this historical period as my case studies, I argue that one of the ways in which Black writers of this decade have imagined the possibility of interracial love—with all its political pitfalls and ethical imperatives —is through the trope of passing. -

Fiestas and Fervor: Religious Life and Catholic Enlightenment in the Diocese of Barcelona, 1766-1775

FIESTAS AND FERVOR: RELIGIOUS LIFE AND CATHOLIC ENLIGHTENMENT IN THE DIOCESE OF BARCELONA, 1766-1775 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Andrea J. Smidt, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2006 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Dale K. Van Kley, Adviser Professor N. Geoffrey Parker Professor Kenneth J. Andrien ____________________ Adviser History Graduate Program ABSTRACT The Enlightenment, or the "Age of Reason," had a profound impact on eighteenth-century Europe, especially on its religion, producing both outright atheism and powerful movements of religious reform within the Church. The former—culminating in the French Revolution—has attracted many scholars; the latter has been relatively neglected. By looking at "enlightened" attempts to reform popular religious practices in Spain, my project examines the religious fervor of people whose story usually escapes historical attention. "Fiestas and Fervor" reveals the capacity of the Enlightenment to reform the Catholicism of ordinary Spaniards, examining how enlightened or Reform Catholicism affected popular piety in the diocese of Barcelona. This study focuses on the efforts of an exceptional figure of Reform Catholicism and Enlightenment Spain—Josep Climent i Avinent, Bishop of Barcelona from 1766- 1775. The program of “Enlightenment” as sponsored by the Spanish monarchy was one that did not question the Catholic faith and that championed economic progress and the advancement of the sciences, primarily benefiting the elite of Spanish society. In this context, Climent is noteworthy not only because his idea of “Catholic Enlightenment” opposed that sponsored by the Spanish monarchy but also because his was one that implicitly condemned the present hierarchy of the Catholic Church and explicitly ii advocated popular enlightenment and the creation of a more independent “public sphere” in Spain by means of increased literacy and education of the masses. -

Days & Hours for Social Distance Walking Visitor Guidelines Lynden

53 22 D 4 21 8 48 9 38 NORTH 41 3 C 33 34 E 32 46 47 24 45 26 28 14 52 37 12 25 11 19 7 36 20 10 35 2 PARKING 40 39 50 6 5 51 15 17 27 1 44 13 30 18 G 29 16 43 23 PARKING F GARDEN 31 EXIT ENTRANCE BROWN DEER ROAD Lynden Sculpture Garden Visitor Guidelines NO CLIMBING ON SCULPTURE 2145 W. Brown Deer Rd. Do not climb on the sculptures. They are works of art, just as you would find in an indoor art Milwaukee, WI 53217 museum, and are subject to the same issues of deterioration – and they endure the vagaries of our harsh climate. Many of the works have already spent nearly half a century outdoors 414-446-8794 and are quite fragile. Please be gentle with our art. LAKES & POND There is no wading, swimming or fishing allowed in the lakes or pond. Please do not throw For virtual tours of the anything into these bodies of water. VEGETATION & WILDLIFE sculpture collection and Please do not pick our flowers, fruits, or grasses, or climb the trees. We want every visitor to be able to enjoy the same views you have experienced. Protect our wildlife: do not feed, temporary installations, chase or touch fish, ducks, geese, frogs, turtles or other wildlife. visit: lynden.tours WEATHER All visitors must come inside immediately if there is any sign of lightning. PETS Pets are not allowed in the Lynden Sculpture Garden except on designated dog days.