UNDERSTANDING MANUMISSION, SELF-PURCHASE, and FREEDOM in 19Th CENTURY BERMUDA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Mexico New Mexico

NEW MEXICO NEWand MEXICO the PIMERIA ALTA THE COLONIAL PERIOD IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEst edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves NEW MEXICO AND THE PIMERÍA ALTA NEWand MEXICO thePI MERÍA ALTA THE COLONIAL PERIOD IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEst edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO Boulder © 2017 by University Press of Colorado Published by University Press of Colorado 5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C Boulder, Colorado 80303 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of Association of American University Presses. The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University. ∞ This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). ISBN: 978-1-60732-573-4 (cloth) ISBN: 978-1-60732-574-1 (ebook) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Douglass, John G., 1968– editor. | Graves, William M., editor. Title: New Mexico and the Pimería Alta : the colonial period in the American Southwest / edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves. Description: Boulder : University Press of Colorado, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016044391| ISBN 9781607325734 (cloth) | ISBN 9781607325741 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Spaniards—Pimería Alta (Mexico and Ariz.)—History. | Spaniards—Southwest, New—History. | Indians of North America—First contact with Europeans—Pimería Alta (Mexico and Ariz.)—History. -

American Eel Anguilla Rostrata

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the American Eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the American eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 71 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge V. Tremblay, D.K. Cairns, F. Caron, J.M. Casselman, and N.E. Mandrak for writing the status report on the American eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada, overseen and edited by Robert Campbell, Co-chair (Freshwater Fishes) COSEWIC Freshwater Fishes Species Specialist Subcommittee. Funding for this report was provided by Environment Canada. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur l’anguille d'Amérique (Anguilla rostrata) au Canada. Cover illustration: American eel — (Lesueur 1817). From Scott and Crossman (1973) by permission. ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2004 Catalogue No. CW69-14/458-2006E-PDF ISBN 0-662-43225-8 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – April 2006 Common name American eel Scientific name Anguilla rostrata Status Special Concern Reason for designation Indicators of the status of the total Canadian component of this species are not available. -

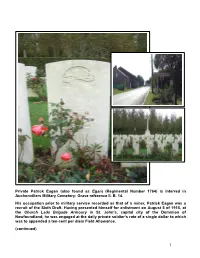

Private Patrick Eagan (Also Found As Egan) (Regimental Number 1764) Is Interred in Auchonvillers Military Cemetery: Grave Reference II

Private Patrick Eagan (also found as Egan) (Regimental Number 1764) is interred in Auchonvillers Military Cemetery: Grave reference II. B. 14. His occupation prior to military service recorded as that of a miner, Patrick Eagan was a recruit of the Sixth Draft. Having presented himself for enlistment on August 5 of 1915, at the Church Lads Brigade Armoury in St. John’s, capital city of the Dominion of Newfoundland, he was engaged at the daily private soldier’s rate of a single dollar to which was to appended a ten-cent per diem Field Allowance. (continued) 1 Just one day after having enlisted, on August 6 he was to return to the CLB Armoury on Harvey Road. On this second occasion Patrick Eagan was to undergo a medical examination, a procedure which was to pronounce him as being…Fit for Foreign Service. And it must have been only hours afterwards again that there then came the final formality of his enlistment: attestation. On the same August 6 he pledged his allegiance to the reigning monarch, George V, at which moment Patrick Eagan thus became…a soldier of the King. A further, and lengthier, waiting-period was now in store for the recruits of this draft, designated as ‘G’ Company, before they were to depart from Newfoundland for…overseas service. Private Eagan, Regimental Number 1764, was not to be again called upon until October 27, after a period of twelve weeks less two days. Where he was to spend this intervening time appears not to have been recorded although he possibly returned temporarily to his work and perhaps would have been able to spend time with family and friends in the Bonavista Bay community of Keels – but, of course, this is only speculation. -

American Eel (Anguilla Rostrata )

American Eel (Anguilla rostrata ) Abstract The American eel ( Anguilla rostrata ) is a freshwater eel native in North America. Its smooth, elongated, “snake-like” body is one of the most noted characteristics of this species and the other species in this family. The American Eel is a catadromous fish, exhibiting behavior opposite that of the anadromous river herring and Atlantic salmon. This means that they live primarily in freshwater, but migrate to marine waters to reproduce. Eels are born in the Sargasso Sea and then as larvae and young eels travel upstream into freshwater. When they are fully mature and ready to reproduce, they travel back downstream into the Sargasso Sea,which is located in the Caribbean, east of the Bahamas and north of the West Indies, where they were born (Massie 1998). This species is most common along the Atlantic Coast in North America but its range can sometimes even extend as far as the northern shores of South America (Fahay 1978). Context & Content The American Eel belongs in the order of Anguilliformes and the family Anguillidae, which consist of freshwater eels. The scientific name of this particular species is Anguilla rostrata; “Anguilla” meaning the eel and “rostrata” derived from the word rostratus meaning long-nosed (Ross 2001). General Characteristics The American Eel goes by many common names; some names that are more well-known include: Atlantic eel, black eel, Boston eel, bronze eel, common eel, freshwater eel, glass eel, green eel, little eel, river eel, silver eel, slippery eel, snakefish and yellow eel. Many of these names are derived from the various colorations they have during their lifetime. -

Newfoundland and Labrador

Clean Fuel Standard CASE STUDY: NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR Snapshot of macro effects for Newfoundland and Labrador: Direct compliance costs: $264 million ($1,040 per employed person) Capital removed from economy: $0.7 billion Job losses: 1,261 Increase in cost of gasoline: 10.5% Increase in cost of natural gas: n/a Main sectors affected: Wholesale and retail sales (221 jobs) Banking, Finance and Professional Services (227 jobs) Entertainment, including Restaurants (136 jobs) Other Manufacturing (191 jobs) Construction (117 jobs) Household Effects Due to Newfoundland and Labrador's (NL) unique geographic location, all import and export goods must be transported via cargo boats and planes (Transportation Directory of NFL, 2003), making the island particularly fuel-dependent. Thus transportation fuels like gasoline are an essential energy source for providing goods and services to the majority of residents of NL. Figure 1. Nominal gasoline price in Newfoundland and Labrador, 1993-2019. Source: Statistics Canada 2020c Figure 1 shows the historical price of gasoline in St. John’s since 1993.1 According to Statistics 1Due to the availability of gasoline price data by major cities, the cost estimate for households of additional gasoline expenses at the provincial level uses major city-level average prices as a proxy for the corresponding province. 1 Canada, 2016 Census of Population, there were 218,675 households in NL. The average annual gasoline price in St. John’s was $1.27 per litre in 2018 (Statistics Canada, 2020c). Our model estimates that of the17% increase in production costs about 10.5% would be passed on to consumers in NL which implies the average purchase price would have been $1.40 per litre of gasoline in 2018. -

Alien Love- Passing, Race, and the Ethics of the Neighbor in Postwar

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Alien Love: Passing, Race, and the Ethics of the Neighbor in Postwar African American Novels, 1945-1956 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy In English By Hannah Wonkyung Nahm 2021 © Copyright by Hannah Wonkyung Nahm 2021 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Alien Love: Passing, Race, and the Ethics of the Neighbor in Postwar African American Novels, 1945-1956 by Hannah Wonkyung Nahm Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2021 Professor King-Kok Cheung, Co-Chair Professor Richard Yarborough, Co-Chair This dissertation examines Black-authored novels featuring White (or White-passing) protagonists in the post-World War II decade (1945-1956). Published during the fraught postwar political climate of agitation for integration and the continual systematic racism, many novels by Black authors addressed the urgent topic of interracial relationality, probing the tabooed question of whether Black and White can abide in love and kinship. One of the prominent—and controversial—literary strategies sundry Black novelists used in this decade was casting seemingly raceless or ambiguously-raced characters. Collectively, these novels generated a mixture of critical approval and dismissal in their time and up until recently, marginalized from the African American literary tradition. Even more critically overlooked than the ostensibly raceless project was the strategic mobilization of the trope of passing by some midcentury Black ii writers to imagine the racial divide and possible reconciliation. This dissertation intersects passing with postwar Black fiction that features either racially-anomalous or biracial central characters. Examining three novels from this historical period as my case studies, I argue that one of the ways in which Black writers of this decade have imagined the possibility of interracial love—with all its political pitfalls and ethical imperatives —is through the trope of passing. -

View a List of Commonwealth Visits Since 1952

COMMONWEALTH VISITS SINCE 1952 Kenya (visiting Sagana Lodge, Kiganjo, where The 6 February 1952 Queen learned of her Accession) 24-25 November 1953 Bermuda 25-27 November 1953 Jamaica 17-19 December 1953 Fiji 19-20 December 1953 Tonga 23 December 1953 - 30 January 1954 New Zealand Australia (New South Wales (NSW), Australian Capital Territory (ACT), Tasmania, Victoria, South Australia, 3 February - 1 April 1954 Queensland, Western Australia) 5 April 1954 Cocos Islands 10-21 April 1954 Ceylon 27 April 1954 Aden 28-30 April 1954 Uganda 3-7 May 1954 Malta 10 May 1954 Gibraltar 28 January - 16 February 1956 Nigeria 12-16 October 1957 Canada (Ontario) Canada (opening of St. Lawrence Seaway, Newfoundland, Quebec, Ontario, Alberta, British Columbia, Yukon, Northwest Territories, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Prince 18 June - 1 August 1959 Edward Island, Nova Scotia) 21 January - 1 February 1961 India 1-16 February 1961 Pakistan 16-26 February 1961 India 1-2 March 1961 India 9-20 November 1961 Ghana 25 November - 1 December 1961 Sierra Leone 3-5 December 1961 Gambia Canada (refuelling in Edmonton and overnight stop in 30 January - 1 February 1963 Vancouver) 2-3 February 1963 Fiji 6-18 February 1963 New Zealand Australia (ACT, South Australia, Victoria, Tasmania, NSW, Queensland, Northern Territory, Western 18 February - 27 March 1963 Australia) 5-13 October 1964 Canada (Prince Edward Island, Quebec, Ottawa) 1 February 1966 Canada (refuelling in Newfoundland) 1 February 1966 Barbados 4-5 February 1966 British Guiana 7-9 February 1966 Trinidad 10 February 1966 Tobago 11 February 1966 Grenada 13 February 1966 St. -

Self-Reliance: the Role of Anti-Industrial Individualism in Abolitionism

Self-Reliance: The Role of Anti-Industrial Individualism in Abolitionism Mid-nineteenth century America witnessed an explosion of civil unrest; changes in political rhetoric, religious revivals, economic revolutions, and unparalleled reforms combined to make the period one of the most volatile in U.S. history. Unmitigated industrialization left Americans confused and restless, and countless reform movements emerged as they attempted to control their surroundings. Many historians contribute these reforms to mass movements such as the Second Great Awakening and the homogenization of the middle class, arguing that large movements gave confused Americans a sense of community. However, in the wake of post-industrial confusion, Americans looked to themselves for security from their constantly changing world, and they saw the impact that they alone could make on society. Americans decried the state of society’s forgotten- including slaves- and the individualism of the post-industrial U.S. inspired a militant abolitionism that led the nation into the bloodiest war in its history. The true source of nineteenth-century reforms thus lies not in mass movements but in a new birth of anti- industrial American individualism. At the turn of the eighteenth century, America was relatively tranquil; picturesque yeoman farmers dominated the countryside, and self-employed artisans filled the cities. However, over the next fifty years, the northern economy underwent an incredible industrial transformation. Steamboats, canals, railways, and other new technologies halved overland This 1839 engraving by W.H. Bartlett features a view of the Erie Canal as it passes through Lockport, New shipping costs and connected previously remote York (Bartlett). The Erie Canal was one of the areas through commerce (McPherson, p. -

1 Final Draft Prior to Minor Editorial Changes and Type Setting. Published In: Nature Geoscience, V. 5, P. 676-677 (2012) Proble

Final draft prior to minor editorial changes and type setting. Published in: Nature Geoscience, v. 5, p. 676-677 (2012) Problematic plate reconstruction Brian E. Tucholke and Jean-Claude Sibuet To the Editor – As has been previously proposed1,2, Bronner et al.3 suggest that opening of the rift between Newfoundland and Iberia involved exhumation of mantle rocks until 112 million years ago, subsequent seafloor spreading, and crustal thickening along the high-amplitude J magnetic anomaly by magma that propagated from the Southeast Newfoundland Ridge area. Conventionally, the anomalous magnetism and basement ridges associated with the J anomaly north of the Newfoundland-Gibraltar Fracture Zone are thought to have formed about 125 million years ago at chron M02,3 (Fig. 1a), although the crust probably experienced some later magmatic overprinting4. The M0 age would make their formation simultaneous with that of the similar J anomaly and basement ridges (the J Anomaly Ridge and Madeira Tore Rise) along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge to the south5,6 and place them within a zone of exhumed mantle in the Newfoundland-Iberia rift2,3. In contrast, Bronner et al.3 propose that the J anomaly and associated basement ridges were formed by later magmatism (about 112 million years ago) that marked the end of mantle exhumation in the rift. We argue here that constraints from plate tectonic reconstructions render this possibility untenable. The magnetic model central to the Bronner et al.3 paper is plausible (although no more so than models based on M-series geomagnetic reversal data2,7-9), but it is problematic in terms of plate reconstructions. -

The Falkland Islands & Their Adjacent Maritime Area

International Boundaries Research Unit MARITIME BRIEFING Volume 2 Number 3 The Falkland Islands and their Adjacent Maritime Area Patrick Armstrong and Vivian Forbes Maritime Briefing Volume 2 Number 3 ISBN 1-897643-26-8 1997 The Falkland Islands and their Adjacent Maritime Area by Patrick Armstrong and Vivian Forbes Edited by Clive Schofield International Boundaries Research Unit Department of Geography University of Durham South Road Durham DH1 3LE UK Tel: UK + 44 (0) 191 334 1961 Fax: UK +44 (0) 191 334 1962 E-mail: [email protected] www: http://www-ibru.dur.ac.uk The Authors Patrick Armstrong teaches biogeography and environmental management in the Geography Department of the University of Western Australia. He also cooperates with a colleague from that University’s Law School in the teaching of a course in environmental law. He has had a long interest in remote islands, and has written extensively on this subject, and on the life and work of the nineteenth century naturalist Charles Darwin, another devotee of islands. Viv Forbes is a cartographer, map curator and marine geographer based at the University of Western Australia. His initial career was with the Merchant Navy, and it was with them that he spent many years sailing the waters around Australia, East and Southeast Asia. He is the author of a number of publications on maritime boundaries, particularly those of the Indian Ocean region. Acknowledgements Travel to the Falkland Islands for the first author was supported by a grant from the National Geographic Society Committee for Research and Exploration. Part of the material in this Briefing was presented as a paper at the 4th International Boundaries Conference, IBRU, Durham, July 1996; travel by PHA to this conference was supported by the Faculty of Science of the University of Western Australia. -

White Writers, Race Matters Fictions of Racial Liberalism from Stowe to Stockett

White Writers, Race Matters fictions of racial liberalism from stowe to stockett Gregory S. Jay 1 0003185048.INDD 3 Dictionary: NOAD 8/1/2017 9:35:46 PM { Contents } Introduction: Toward a Literary History of Racial Liberalism 3 1. Sympathy in Action: Stowe, Twain, and the Origins of Liberal Race Fiction 42 2. How Does It Feel to Be a Trademark?: Fannie Hurst’s Imitation 93 of Life 3. Jew Like Me: Empathy and Antisemitism in Laura Zametkin 142 Hobson’s Gentleman’s Agreement 4. Desegregating Liberalism: Radical Identifications in Lillian 185 Smith’s Strange Fruit and Killers of the Dream 5. Queer Children and Representative Men: Harper Lee’s 236 To Kill a Mockingbird 6. Speaking of Abjection: White Writing and Black Resistance in 286 Kathryn Stockett’s The Help 327 7. Afterword Notes 331 339 Works Cited 353 Index 0003185048.INDD 11 Dictionary: NOAD 8/1/2017 9:35:46 PM Introduction toward a literary history of racial liberalism The “protest” novel, so far from being disturbing, is an accepted and comforting aspect of the American scene, ramifying that framework we believe to be so necessary. Whatever unsettling questions are raised are evanescent, titillating; remote, for this has nothing to do with us, it is safely ensconced in the social arena, where, indeed, it has nothing to do with anyone, so that finally we receive a very definite thrill of virtue from the fact that we are reading such a book at all. This report from the pit reassures us of its reality and its darkness and of our own salvation; and “As long as such books are being published,” an American liberal once said to me, “everything will be all right.” —james baldwin, “Everybody’s Protest Novel” What explains the enduring popularity of white-authored protest fiction about racism in America? This book began with that seem- ingly simple question some years ago, following the spectacular suc- cess of Kathryn Stockett’s 2009 novel The Help and its Hollywood film adaptation. -

Back to the Future: Taking a Trip Back in Order to Move Forward in Octavia Butler’S Kindred Zakary H

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Undergraduate Honors Theses Student Works 5-2014 Back to the Future: Taking a Trip Back in Order to Move Forward in Octavia Butler’s Kindred Zakary H. LaFaver East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/honors Part of the Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons Recommended Citation LaFaver, Zakary H., "Back to the Future: Taking a Trip Back in Order to Move Forward in Octavia Butler’s Kindred" (2014). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 215. https://dc.etsu.edu/honors/215 This Honors Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Back to the Future: Taking a Trip Back in Order to Move Forward in Octavia Butler’s Kindred Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of Honors By Zakary LaFaver The Honors College English Honors-in-Discipline East Tennessee State University May 8, 2014 Zakary LaFaver, Author Michael Cody, Faculty Mentor Karen Kornweibel, Faculty Reader Leslie McCallister, Faculty Reader LaFaver 2 Introduction Although Octavia Butler’s 1979 novel Kindred is often classified as science fiction, Butler says, “Kindred is fantasy. I mean literally, it is fantasy. There’s no science in Kindred” (qtd. in Kenan 495). The central character of the novel is Dana, an African American woman living in Los Angeles, California, in 1976.