Austria and Hungary 1850

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BURGENLAND Than Samplinglocal and Youhave Region

© Lonely Planet Publications 188 Burgenland Often given a wide berth by tourists, Burgenland is all but the typical Austria you hear of or read about. It has neither bombastic architecture nor deep lakes and soaring mountains. On the contrary, it is small and sleepy, and in large sections a flat province situated on the border with Hungary. Even the jewel in its crown – Neusiedler See – has dried up and disappeared several times in its natural history – most recently in the mid-19th century. This is the kind of place where everyday life takes precedence, but it is precisely this ‘every- day’ aspect that makes it interesting. The province receives a reputed 300 days of sunshine a year; couple this with a rich soil base and a wine history dating back to pre-Roman times, and you have Austria’s best wine-producing region. What better way to spend an afternoon than sampling local Weine (wines) in a Heuriger (wine tavern) under a warm sun? Throw in the shallow Neusiedler See and a section of it that is now the Neusiedler See-Seewinkel National Park, tack on a bike path that leads into the park and through Hungary before re- emerging in Austria, and add a swampy, medieval town such as Rust, and you might find yourself fascinated by Burgenland’s charms. Stork-spotters will be in their element here in summer, when feathered friends populate the roofs of several towns near the lake – including Rust, one of the nicest places to observe BURGENLAND BURGENLAND them. Although it does have a handful of interesting cultural sights, such as Schloss Ester- házy in Eisenstadt, the province’s small capital, Burgenland is more a place where people are content to enjoy good wine and food, and relax in the great outdoors. -

Report for Austria– Questionnaire Related the Administration Control

ADMINISTRATIVE JUSTICE IN EUROPE – Report for Austria– Questionnaire related the administration control list and typology in the 25 Member States of the European Union Preliminary. 1. Administration jurisdictional control was one typical concern of the liberal streams in the 19th century. In Austria, “the Reichsgericht”, a precursor of the Constitutional Court, was created by the December 1867 constitution which also planned creation of a Supreme Administrative Court (hereafter “the Verwaltungsgerichtshof”). However, this project was only fulfilled in 1876. Following this, the Verwaltungsgerichtshof played a decisive role in developing the legal protection system in Austria, establishing fundamental principles for administrative procedural law. Between 1934 and 1938, the Constitutional Court and the Verwaltungsgerichtshof merged to become “the Bundesgerichtshof”. Several judges were retired for political reasons. The introductions of Chambers with extended composition and of actions for administrative failure to act were significant reforms. After 1938, “the Bundesgerichtshof” lost its authority as Constitutional Court as well as several of its administrative jurisdiction authorities. Several judges were retired for political reasons. In 1940 “the Bundesgerichtshof” became “the Verwaltungsgerichtshof in Vienna” which was an administrative authority of the Reich. In 1941, the Verwaltungsgerichtshof became the “Vienna Außensenat” of the “Reichsverwaltungsgericht” by forming an organisational association with other German administrative courts. A few weeks after the Austrian declaration of independence in 1945, Chancellor Renner commissioned Mr. Coreth to revive the Verwaltungsgerichtshof which took up its duties again on 7th December 1945. The legal text on the Verwaltungsgerichtshof was amended and reissued several times but, in substance, it is still in force today. In 1945, the Constitutional Court was re-established with the same capacities as 1933 and it began carrying out its duties again in 1946. -

On Burgenland Croatian Isoglosses Peter

Dutch Contributions to the Fourteenth International Congress of Slavists, Ohrid: Linguistics (SSGL 34), Amsterdam – New York, Rodopi, 293-331. ON BURGENLAND CROATIAN ISOGLOSSES PETER HOUTZAGERS 1. Introduction Among the Croatian dialects spoken in the Austrian province of Burgenland and the adjoining areas1 all three main dialect groups of central South Slavic2 are represented. However, the dialects have a considerable number of characteris- tics in common.3 The usual explanation for this is (1) the fact that they have been neighbours from the 16th century, when the Ot- toman invasions caused mass migrations from Croatia, Slavonia and Bos- nia; (2) the assumption that at least most of them were already neighbours before that. Ad (1) Map 14 shows the present-day and past situation in the Burgenland. The different varieties of Burgenland Croatian (henceforth “BC groups”) that are spoken nowadays and from which linguistic material is available each have their own icon. 5 1 For the sake of brevity the term “Burgenland” in this paper will include the adjoining areas inside and outside Austria where speakers of Croatian dialects can or could be found: the prov- ince of Niederösterreich, the region around Bratislava in Slovakia, a small area in the south of Moravia (Czech Republic), the Hungarian side of the Austrian-Hungarian border and an area somewhat deeper into Hungary east of Sopron and between Bratislava and Gyǡr. As can be seen from Map 1, many locations are very far from the Burgenland in the administrative sense. 2 With this term I refer to the dialect continuum formerly known as “Serbo-Croatian”. -

Sources for Genealogical Research at the Austrian War Archives in Vienna (Kriegsarchiv Wien)

SOURCES FOR GENEALOGICAL RESEARCH AT THE AUSTRIAN WAR ARCHIVES IN VIENNA (KRIEGSARCHIV WIEN) by Christoph Tepperberg Director of the Kriegsarchiv 1 Table of contents 1. The Vienna War Archives and its relevance for genealogical research 1.1. A short history of the War Archives 1.2. Conditions for doing genealogical research at the Kriegsarchiv 2. Sources for genealogical research at the Kriegsarchiv 2. 1. Documents of the military administration and commands 2. 2. Personnel records, and records pertaining to personnel 2.2.1. Sources for research on military personnel of all ranks 2.2.2. Sources for research on commissioned officers and military officials 3. Using the Archives 3.1. Regulations for using personnel records 3.2. Visiting the Archives 3.3. Written inquiries 3.4. Professional researchers 4. Relevant publications 5. Sources for genealogical research in other archives and institutions 5.1. Sources for genealogical research in other departments of the Austrian State Archives 5.2. Sources for genealogical research in other Austrian archives 5.3. Sources for genealogical research in archives outside of Austria 5.3.1. The provinces of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and its “successor states” 5.3.2. Sources for genealogical research in the “successor states” 5.4. Additional points of contact and practical hints for genealogical research 2 1. The Vienna War Archives and its relevance for genealogical research 1.1. A short history of the War Archives Today’s Austrian Republic is a small country, but from 1526 to 1918 Austria was a great power, we can say: the United States of Middle and Southeastern Europe. -

The Empire in the Provinces: the Case of Carinthia

religions Article The Empire in the Provinces: The Case of Carinthia Helmut Konrad Institut für Geschichte, Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz, Attemsgasse 8/II, [505] 8010 Graz, Austria; [email protected] Academic Editors: Malachi Hacohen and Peter Iver Kaufman Received: 16 May 2016; Accepted: 1 August 2016; Published: 5 August 2016 Abstract: This article examines the legacy of the Habsburg Monarchy in the First Austrian Republic, both in the capital, Vienna, and in the province of Carinthia. It concludes that Social Democracy, often cited as one of the six ingredients that held the old Empire together, took on distinct forms in the Republic’s different federal states. The scholarly literature on the post-1918 “heritage” of the Monarchy therefore needs to move beyond monolithic generalizations and toward regionally focused comparative studies. Keywords: empire; socialism; Jews; Habsburg Monarchy; Austria; Vienna; Carinthia; German Nationalism; Sprachenkampf 1. Introduction Which forms did the ideas take that allowed the Habsburg monarchy to persist, despite the diversity of nationalisms present in the small Republic of German-Austria, for so long after the end of the First World War? What was the “glue” that held this multiethnic empire together, when its collapse had been predicted since 1848, and which of its elements continued to exist beyond 1918? How was this heritage expressed in the different regions of the new republic? At least six factors can be identified as ingredients of the “glue” that held the monarchy together: first, the Emperor, a figure who symbolized the fusion of the complex linguistic, ethnic and religious components of the Habsburg state; second, the administrative officials, who were loyal to the Emperor and worked in the ubiquitous and even architecturally similar buildings of the Monarchy’s district authorities and train stations; third, the army, whose members promoted the imperial ideals through their long terms of service and acknowledged linguistic diversity. -

Austerity and the Rise of the Nazi Party Gregori Galofré-Vilà, Christopher M

Austerity and the Rise of the Nazi party Gregori Galofré-Vilà, Christopher M. Meissner, Martin McKee, and David Stuckler NBER Working Paper No. 24106 December 2017, Revised in September 2020 JEL No. E6,N1,N14,N44 ABSTRACT We study the link between fiscal austerity and Nazi electoral success. Voting data from a thousand districts and a hundred cities for four elections between 1930 and 1933 shows that areas more affected by austerity (spending cuts and tax increases) had relatively higher vote shares for the Nazi party. We also find that the localities with relatively high austerity experienced relatively high suffering (measured by mortality rates) and these areas’ electorates were more likely to vote for the Nazi party. Our findings are robust to a range of specifications including an instrumental variable strategy and a border-pair policy discontinuity design. Gregori Galofré-Vilà Martin McKee Department of Sociology Department of Health Services Research University of Oxford and Policy Manor Road Building London School of Hygiene Oxford OX1 3UQ & Tropical Medicine United Kingdom 15-17 Tavistock Place [email protected] London WC1H 9SH United Kingdom Christopher M. Meissner [email protected] Department of Economics University of California, Davis David Stuckler One Shields Avenue Università Bocconi Davis, CA 95616 Carlo F. Dondena Centre for Research on and NBER Social Dynamics and Public Policy (Dondena) [email protected] Milan, Italy [email protected] Austerity and the Rise of the Nazi party Gregori Galofr´e-Vil`a Christopher M. Meissner Martin McKee David Stuckler Abstract: We study the link between fiscal austerity and Nazi electoral success. -

Austria FULL Constitution

AUSTRIA THE FEDERAL CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF 1920 as amended in 1929 as to Law No. 153/2004, December 30, 2004 Table of Contents CHAPTER I General Provisions European Union CHAPTER II Legislation of the Federation CHAPTER III Federal Execution CHAPTER IV Legislation and Execution by the Länder CHAPTER V Control of Accounts and Financial Management CHAPTER VI Constitutional and Administrative Guarantees CHAPTER VII The Office of the People’s Attorney ( Volksanwaltschaft ) CHAPTER VIII Final Provisions CHAPTER I General Provisions European Union A. General Provisions Article 1 Austria is a democratic republic. Its law emanates from the people. Article 2 (1) Austria is a Federal State. (2) The Federal State is constituted from independent Länder : Burgenland, Carinthia, Lower Austria, Upper Austria, Salzburg, Styria, Tirol, Vorarlberg and Vienna. Article 3 (1) The Federal territory comprises the territories ( Gebiete ) of the Federal Länder . (2) A change of the Federal territory, which is at the same time a change of a Land territory (Landesgebiet ), just as the change of a Land boundary inside the Federal territory, can—apart from peace treaties—take place only from harmonizing constitutional laws of the Federation (Bund ) and the Land , whose territory experiences change. Article 4 (1) The Federal territory forms a unitary currency, economic and customs area. (2) Internal customs borders ( Zwischenzollinien ) or other traffic restrictions may not be established within the Federation. Article 5 (1) The Federal Capital and the seat of the supreme bodies of the Federation is Vienna. (2) For the duration of extraordinary circumstances the Federal President, on the petition of the Federal Government, may move the seat of the supreme bodies of the Federation to another location in the Federal territory. -

Dismantled Once, Diverged Forever? a Quasi-Natural Experiment of Red Army’ Disassemblies in Post-WWII Europe

Dismantled once, diverged forever? A quasi-natural experiment of Red Army’ disassemblies in post-WWII Europe – EXTENDED ABSTRACT WITH PRELIMINARY RESULTS – I identify the long-run spatial effects of an exogenous decline in the capital stock on population growth and sectoral change. After WWII, South Austria has been the only region in entire Europe that was initially liberated but not permanently occupied by the Red Army. The demarcation line between the liberation forces was fully exogenous, solely driven by the respective velocity of their jeeps. I use the liberation and the 77 days lasting temporary occupation of Styria after WWII to estimate causal inferences of dismantling and pillaging activities by both the Red Army and its soldiers. First estimates with a sample of direct demarcation line border municipalities indicate a relative population decline of Red Army liberated municipalities of around 15% compared to direct adjacent municipalities. In contrast, pre-WWII population growth shows no differences. A panel from 1934 to 2011 with demographic and economic variables will be constructed. A Re- gression Discontinuity approach will be employed to estimate discontinuities across the tempo- rary demarcation line on population dynamics and on sectoral change during the last eight dec- ades. JEL-Codes: J11, N14, N94, R12, R23 Keywords: Regional Economic Activity, Regional Spillovers, Dismantling, Austria Christian Ochsner Ifo Institute – Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich Dresden Branch Einsteinstr. 3 01069 Dresden, Germany Phone: +49(0)351/26476-26 [email protected] This version: March 2017 1 1. Introduction (and first results) Economic activity is unequally distributed across space. -

Austria: Vienna

Guide to Catholic-Related Records outside the U.S. about Native Americans See User Guide for help on interpreting entries Archdiocese of Vienna new 2004 AUSTRIA, VIENNA Archdiocese of Vienna Archives AT- 2 A-1010 Wollzeile 2 Wien, Oesterreich Phone 43 1 51552 http://stephanscom.at/ Hours: Monday, Tuesday, and Thursday, 8:30-1:00, 2:00-4:00; and Friday, 8:30-12:00 Access: Some restrictions apply Copying facilities: Yes History of the Leopoldine Society 1827 Bishop Edward D. Fenwick, O.P. of Cincinnati, Ohio sent Reverend John Fréderic Résé to Europe to recruit German- speaking priests and financial assistance for the Cincinnati Diocese; Reverend Samuel Mazzuchelli, O.P. (1806-1864) was among those recruited 1829 In response, the Leopoldine Society (Leopoldinen Stetiftung) was established in Vienna with headquarters at the Augustinian monastery; it solicited German- speaking priests and financial assistance from the dioceses of the Austrian Empire for needy dioceses in the United States, some of which had American Indian missions 1830-1910 The Leopoldine Society donated about $680,500 (3,402,000 kronen) to U.S. dioceses; those with Indian missions that received notable funding included Boise, Cincinnati, Detroit, Grand Rapids, Green Bay, Lead (later renamed Rapid City), Marquette, Nesqually (later renamed Seattle), Oregon (later renamed Portland in Oregon), and Tucson Before 1850 Due to efforts by the Leopoldine Society, several priests from the Austrian Empire emigrated to the United States; those who became missionaries to American Indians include Reverend Frederic I. Baraga (first bishop of the Diocese of Marquette, Michigan), Reverend Joseph F. Buh, Reverend Ignatius Mrak (second bishop of the Diocese of Marquette, Michigan), Reverend Francis Pierz, and Reverend Otto Skolla, O.F.M. -

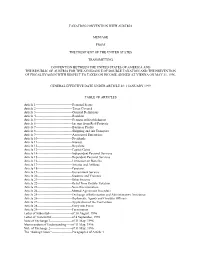

Taxation Convention with Austria Message from The

TAXATION CONVENTION WITH AUSTRIA MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES TRANSMITTING CONVENTION BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE REPUBLIC OF AUSTRIA FOR THE AVOIDANCE OF DOUBLE TAXATION AND THE PREVENTION OF FISCAL EVASION WITH RESPECT TO TAXES ON INCOME, SIGNED AT VIENNA ON MAY 31, 1996. GENERAL EFFECTIVE DATE UNDER ARTICLE 28: 1 JANUARY 1999 TABLE OF ARTICLES Article 1----------------------------------Personal Scope Article 2----------------------------------Taxes Covered Article 3----------------------------------General Definitions Article 4----------------------------------Resident Article 5----------------------------------Permanent Establishment Article 6----------------------------------Income from Real Property Article 7----------------------------------Business Profits Article 8----------------------------------Shipping and Air Transport Article 9----------------------------------Associated Enterprises Article 10--------------------------------Dividends Article 11--------------------------------Interest Article 12--------------------------------Royalties Article 13--------------------------------Capital Gains Article 14--------------------------------Independent Personal Services Article 15--------------------------------Dependent Personal Services Article 16--------------------------------Limitation on Benefits Article 17--------------------------------Artistes and Athletes Article 18--------------------------------Pensions Article 19--------------------------------Government Service Article 20--------------------------------Students -

Bezirk Oberpullendorf Ärzte Für Allgemeinmedizin

Ärzte für Allgemeinmedizin Bezirk Oberpullendorf Dr. Reinhold DINHOPEL 7312 Horitschon Mo 07.30 bis 11.00 und 14.30 bis 17.00 Schulgasse 19 Di 10.00 bis 14.00 (02610) 422 29 Do 07.30 bis 11.30 Fr 07.30 bis 11.00 und 14.30 bis 17.00 Dr. Hans-Christian FILZ 7301 Deutschkreutz Mo 07.30 bis 12.00 Neugasse 22 A Mi 07.30 bis 11.30 und 15.00 bis 16.30 (02613) 801 72 Do 07.30 bis 11.30 Fr 07.30 bis 11.30 und 14.30 bis 16.30 Dr. Andreas FISCHER 7444 Mannersdorf/Rabnitz Mo 07.00 bis 12.00 und 16.00 bis 18.00 Hauptstraße 68 Di 07.00 bis 12.00 (02611) 221 40 Mi 07.00 bis 12.00 Fr 07.00 bis 12.00 und 16.00 bis 18.00 Dr. Wolfgang FUCHS, MSC 7304 Großwarasdorf Mo 07.30 bis 12.30 Schulstraße 3B Di 14.00 bis 18.00 (02614) 202 66 Mi 07.30 bis 12.30 Fr 10.00 bis 16.00 Dr. Eva GALUSKA 7361 Lutzmannsburg Mo 07.00 bis 11.30 Schulgasse 13 Di 07.00 bis 11.30 (02615) 873 90 Do 07.00 bis 11.30 Fr 07.00 bis 11.30 und 16.00 bis 17.00 2. Ordination 7452 Unterpullendorf Di 16.00 bis 17.00 Hauptstraße 53 Fr 07. 00 bis 09.00 (0664) 250 26 15 Dr. Silvia GEBHARDT 7453 Steinberg-Dörfl Mo 07.30 bis 12.00 Untere Hauptstraße 10 Di 15.00 bis 16.00 (02612) 8500 Mi 07.30 bis 12.00 Fr 07.30 bis 12.00 und 15.00 bis 17.00 2. -

Low Fertility in Austria and the Czech Republic: Gradual Policy Adjustments

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Sobotka, Tomáš Working Paper Low fertility in Austria and the Czech Republic: Gradual policy adjustments Vienna Institute of Demography Working Papers, No. 2/2015 Provided in Cooperation with: Vienna Institute of Demography (VID), Austrian Academy of Sciences Suggested Citation: Sobotka, Tomáš (2015) : Low fertility in Austria and the Czech Republic: Gradual policy adjustments, Vienna Institute of Demography Working Papers, No. 2/2015, Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW), Vienna Institute of Demography (VID), Vienna This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/110987 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten