The COVID-19 Mirror: Reflecting Science-Society J Relationships Across 11 Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COVID-19 and Political Polarization: Notes on International Studies Australia’S Chinese Communities Vol

PORTAL Journal of ESSAY Multidisciplinary COVID-19 and Political Polarization: Notes on International Studies Australia’s Chinese Communities Vol. 17, No. 1/2 Jan 2021 Mobo Gao Corresponding author: Professor Mobo Gao, School of Social Sciences, University of Adelaide, South Australia 5005 Australia. [email protected] DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/pjmis.v17i1-2.7365 Article History: Received 12/08/2020; Accepted 07/12/2020; Published 28/01/2021 © 2021 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Abstract Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https:// In this article I draw from my personal observations as a participant in two WeChat creativecommons.org/ groups; a group with my university classmates most of whom are now residents of licenses/by/4.0/), allowing Australia, and the other a skilled migrant group based in South Australia. I explore the third parties to copy and main narrative threads of these two groups in relation to their responses to the COVID-19 redistribute the material in any medium or format and to pandemic during the first half of 2020. I argue that the COVID-19 pandemic sharpened the remix, transform, and build political polarization that exists between denouncers of the People’s Republic of China upon the material for any [PRC] and their detractors, and also underlined particular moral dilemmas. purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its Keywords license. COVID-19; China; Chinese Australians; Emotions; Political Polarization Citation: Gao, M. 2021. -

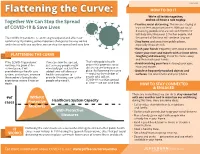

Flattening the Curve: 3/9/2020 We’Re All in This Together, Together We Can Stop the Spread and We All Have a Role to Play

3/23/2020 HOW TO DO IT Flattening the Curve: 3/9/2020 We’re all in this together, Together We Can Stop the Spread and we all have a role to play. • Practice social distancing. This means staying at of COVID-19 & Save Lives least six feet away from others. Without social distancing, people who are sick with COVID-19 will likely infect between 2-3 other people, and The COVID-19 pandemic is continuing to expand and affect our the spread of the virus will continue to grow. community. By making some important changes to the way we live • Stay home and away from public places, and interact with one another, we can stop the spread and save lives. especially if you are sick. • Wash your hands frequently with soap and water. • Cover your nose and mouth with a tissue when FLATTENING THE CURVE coughing and sneezing, throw the tissue away and then wash your hands. If the COVID-19 pandemic If we can slow the spread, That’s why public health orders that promote social • Avoid touching your face including your eyes, continues to grow at the just as many people might nose and mouth. current pace, it will eventually get sick, but the distancing are being put in overwhelm our health care added time will allow our place. By flattening the curve • Disinfect frequently touched objects and system, and in-turn, increase health care system to — reducing the number of surfaces, like door knobs and your phone. the number of people who provide lifesaving care to the people who will get experience severe illness or people who need it. -

Pandemic.Pdf.Pdf

1 PANDEMICS: Past, Present, Future Published in 2021 by the Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Education for Peace and Challenges & Opportunities Sustainable Development, 35 Ferozshah Road, New Delhi 110001, India © UNESCO MGIEP This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike Coordinating Lead Authors: 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ ANANTHA KUMAR DURAIAPPAH by-sa/3.0/ igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be Director, UNESCO MGIEP bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (http:// www.unesco.org/openaccess/terms-use-ccbysa-en). KRITI SINGH Research Officer, UNESCO MGIEP The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they Lead Authors: NANDINI CHATTERJEE SINGH are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Senior Programme Officer, UNESCO MGIEP The publication can be cited as: Duraiappah, A. K., Singh, K., Mochizuki, Y. YOKO MOCHIZUKI (Eds.) (2021). Pandemics: Past, Present and Future Challenges and Opportunities. Head of Policy, UNESCO MGIEP New Delhi. UNESCO MGIEP. SHAHID JAMEEL Coordinating Lead Authors: Director, Trivedi School of Biosciences, Ashoka University Anantha Kumar Duraiappah, Director, UNESCO MGIEP Kriti Singh, Research Officer, UNESCO MGIEP Lead Authors: Nandini Chatterjee Singh, Senior Programme Officer, UNESCO MGIEP Contributing Authors: CHARLES PERRINGS Yoko Mochizuki, Head of Policy, UNESCO MGIEP Global Institute of Sustainability, Arizona State University Shahid Jameel, Director, Trivedi School of Biosciences, Ashoka University W. -

WHO COVID-19 Database Search Strategy (Updated 26 May 2021)

Search purpose: Systematic search of the COVID-19 literature performed Monday through Friday for the WHO Database. Search strategy as of 26 May 2021. Searches performed by Tomas Allen, Kavita Kothari, and Martha Knuth. Use following commands to pull daily new entries: Entry_date:( [20210101 TO 20210120]) Entry_date:( 20210105) Duplicates: Duplicates are found in EndNote and Distillr using the Wichor method. Further screening is done by expert reviewers but some duplicates may still be in the database. Daily Search Strategy: Database Daily Search Strategy Medline (coronavir* OR corona virus* OR corona pandemic* OR betacoronavir* OR covid19 OR covid OR (Ovid) nCoV OR novel CoV OR CoV 2 OR CoV2 OR sarscov2 OR sars2 OR 2019nCoV OR wuhan virus* OR 1946- NCOV19 OR solidarity trial OR operation warp speed OR COVAX OR "ACT-Accelerator" OR BNT162b2 OR comirnaty OR "mRNA-1273" OR CoviShield OR AZD1222 OR Sputnik V OR CoronaVac OR "BBIBP-CorV" OR "Ad26.CoV2.S" OR "JNJ-78436735" OR Ad26COVS1 OR VAC31518 OR EpiVacCorona OR Convidicea OR "Ad5-nCoV" OR Covaxin OR CoviVac OR ZF2001 OR "NVX-CoV2373" OR "ZyCoV-D" OR CIGB 66 OR CVnCoV OR "INO-4800" OR "VIR-7831" OR "UB-612" OR BNT162 OR Soberana 1 OR Soberana 2 OR "B.1.1.7" OR "VOC 202012/01" OR "VOC202012/01" OR "VUI 202012/01" OR "VUI202012/01" OR "501Y.V1" OR UK Variant OR Kent Variant OR "VOC 202102/02" OR "VOC202102/02" OR "B.1.351" OR "VOC 202012/02" OR "VOC202012/02" OR "20H/501.V2" OR "20H/501Y.V2" OR "501Y.V2" OR "501.V2" OR South African Variant OR "B.1.1.28.1" OR "B.1.1.28" OR "B.1.1.248" OR -

Creating the Fastest Economic Recovery

x Chapter 1 Creating the Fastest Economic Recovery The beginning of 2020 ushered in a strong U.S. economy that was delivering job, income, and wealth gains to Americans of all backgrounds. By February 2020, the unemployment rate had fallen to 3.5 percent—the lowest in 50 years— and unemployment rates for minority groups and historically disadvantaged Americans were at or near their lowest points in recorded history. Wages were rising faster for workers than for managers, income and wealth inequality were on the decline, and median incomes for minority households were experienc- ing especially rapid gains. The fruits of this strong labor market expansion from 2017 to 2019 also included lifting 6.6 million people out of poverty, which is the largest three-year drop to start any presidency since the War on Poverty began in 1964. These accomplishments highlight the success of the Trump Administration’s pro-growth, pro-worker policies. The robust state of the U.S. economy in the three years through 2019 led almost all forecasters to expect continued healthy growth through 2020 and beyond. However, in late 2019 and the early months of 2020, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, with origins in the People’s Republic of China, began spreading around the globe and eventually within the United States, causing a pandemic and bringing with it an unprecedented economic and public health crisis. Both the demand and supply sides of the economy suffered sudden and massive shocks due to the pandemic. During the springtime lockdowns aimed at “flattening the curve,” the labor market lost 22.2 million jobs, and the unemployment rate jumped 11.2 percentage points, to 14.7 percent—the largest monthly changes in the series’ histories. -

COVID-19 & the Swedish Conundrum: Part I Why Did Sweden Not Lock

COVID-19 & The Swedish Conundrum: Part I Why did Sweden not lock down? What were they trying to achieve? Prathap Tharyan The world is cautiously trying to emerge from lockdowns People enjoying the sun in Stockholm on April 21, 2020 Jonathan Nackstrand /AFP via Getty images (Business Insider May 4 2020) No Lockdown: Do the Swedes know something the rest of the world does not know? Or are they playing “Russian Roulette” with their “Herd Immunity” strategy? SWEDEN’S RELAXED CORONAVIRUS RESPONSE NO LOCKDOWN IN SWEDEN: A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT IN COMBATING COVID-19 Cafes, bars, restaurants, elementary schools and most businesses, including hair salons and gyms are open and people are allowed to exercise outdoors Parks and public spaces are open Pubs and bars remain open https://edition.cnn.com/2020/04/28/europe/sweden- Photograph: Ali Lorestani/EPA (The Guardian March 23) coronavirus-lockdown-strategy-intl/index.html WHY IS SWEDEN IS ‘DOING NOTHING’? Advice from the Public Health Agency Sweden has recommended good hygiene as part of infection control “Face masks are meant for Sweden’s Public Health Agency healthcare staff and not needed in in does not recommend face masks the community. for the public The best way to protect oneself and others in daily life is to maintain social distancing and good hand hygiene” SWEDISH PUBLIC HEALTH AGENCY RECOMMENDS SOCIAL DISTANCING No large gatherings (50 people max.) Does not apply to schools, public transport, gyms Work from home if possible Keep arms-length distance from others in all public spaces including -

Long-Term Exposure to PM2.5, Facemask Mandates, Stay Home Orders and COVID-19 Incidence in the United States

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Long-Term Exposure to PM2.5, Facemask Mandates, Stay Home Orders and COVID-19 Incidence in the United States Fang Fang 1, Lina Mu 2, Yifang Zhu 3,4, Jianyu Rao 1,5, Jody Heymann 6 and Zuo-Feng Zhang 1,7,8,* 1 Department of Epidemiology, Fielding School of Public Health, University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA; [email protected] (F.F.); [email protected] (J.R.) 2 Department of Epidemiology and Environmental Health, School of Public Health and Health Professions, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York, Buffalo, NY 14214, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Environmental Health Science, University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA; [email protected] 4 Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA 5 Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA 6 WORLD Policy Analysis Center, University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA; [email protected] 7 Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA 8 Center for Human Nutrition, Department of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Long-term PM2.5 exposure might predispose populations to SARS-CoV-2 infection and Citation: Fang, F.; Mu, L.; Zhu, Y.; intervention policies might interrupt SARS-CoV-2 transmission and reduce the risk of COVID-19. -

To the Pandemic Cases of China, Iran, Russia, Belarus and Hungary

AUTHORITARIAN RESPONSE TO THE PANDEMIC CASES OF CHINA, IRAN, RUSSIA, BELARUS AND HUNGARY Edited by Vladislav Inozemtsev AUTHORITARIAN RESPONSE TO THE PANDEMIC CASES OF CHINA, IRAN, RUSSIA, BELARUS AND HUNGARY FREE RUSSIA FOUNDATION JUNE, 2020 Free Russia Foundation Editor Vladislav Inozemtsev Authors Elizabeth Chen Clément Therme Vladislav Inozemtsev Arseny Sivitsky Bálint Madlovics Proofreading Courtney Dobson, Blue Bear Editing Layout Free Russia Designs CONTENTS Introduction 5 Elizabeth Chen. China 7 Clément Therme. Iran 27 Vladislav Inozemtsev. Russia 38 Arseny Sivitsky. Belarus 58 Bálint Madlovics. Hungary 77 Conclusion 94 economic disruptions; China’s GDP contracted by 6.8% INTRODUCTION in the first quarter;6 all major airlines cut up to 90% of their regular flights by April 1;7 the American economy virtually stalled with 38.6 million jobless by the end of 8 The global pandemic caused by a coronavirus, May. In June 2020, the IMF predicted that the American widely known as COVID-19, officially broke out in the economy would contract by 5.9% in 2020 and the EU 9 city of Wuhan in China in late 2019, but most probably it projection stood at 6.7%. While it is difficult to calculate originated from the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Wu- the overall economic effect of the crisis, even the most conservative estimates begin at $6 trillion with an addi- han-based Institute of Virology1 aauthorized to conduct the most sophisticated experiments with different viruses. tional $15 trillion in assets expected to evaporate due to It is also widely believed that the outbreak started three the declining prices of stocks, real estate, and produc- to four months before it was confirmed by the Chinese of- tion facilities. -

Social Media and China's Virus Outbreak

Volume 18 | Issue 14 | Number 6 | Article ID 5418 | Jul 15, 2020 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Social Media and China's Virus Outbreak Anonymous China rules the world” (2009). In an interview Abstract: In the early stage of the coronavirus with the state media CCTV, Jacques praised the outbreak in China, social media were bursting Chinese government’s crisis management with anger and desperation. Many pleaded for capacity in the wake of the pandemic, saying medical help, called for public attention to the that this, “can be a historic moment where unattended and asked for accountability for people come to see what the strengths of the local officials who failed to respond to the Chinese system are.” (Tuwen Ouni 2020) public health crisis in time. But with the epicenter shifting to Europe and NorthThis marked a dramatic turnaround from the America, a series of social media tactics, early stages of the pandemic when there was highlighting China’s successful containment speculation about whether the Chinese efforts, while disparaging foreign countries’ government’s legitimacy might be undermined responses, and spinning the origin of the by the pandemic. Public opinion in China on the coronavirus outbreak, facilitated a nationalist government’s handling of the crisis has also takeover of social media sites in China. experienced a rollercoaster ride, dipping to the bottom in early February and gradually recovering as the pandemic was contained. The state emerged from the crisis stronger than How China rewrites the narrative of the ever, trumpeting that it had led the Chinese coronavirus pandemic on social media people to victory in the war against COVID-19. -

The Economics of a Pandemic: the Case of Covid-19

The economics of a pandemic: the case of Covid-19 Paolo Surico and Andrea Galeotti Professors of Economics at London Business School london.edu Financial support from the European Research Council and the Wheeler Institute is gratefully acknowledged. This Lecture 1. Science 2. Health policies 3. Economics 4. Macroeconomic policies london.edu The economics of a pandemic: The case of Covid-19 2 The enemy Source: The Economist, 14th March 2020 london.edu The economics of a pandemic: The case of Covid-19 3 The basics about Covid-19: what it is • The cause: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) • The disease: Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) • Possible origin in wet animal market in Wuhan, China, early Dec 2019 • A strain of the same virus as SARS-CoV-1, which affected 8,000 people in 2002/03 • 96% DNA match between bat coronavirus and human found in a study from February; suggests link to humans is not direct but through intermediate host • Initially pangolins were suspected, but now seems to not be so; still unclear • Made of 4 proteins and a strand of RNA (molecule which can store genetic information) • One protein is the spike, which gives the crown-like appearance • Two proteins sit in the membrane between the spikes to provide structural integrity • In the membrane, the fourth protein is a scaffold around the genetic material Source: The Economist, 23rd January 2020; Nature: “Mystery deepens over animal source of coronavirus” https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00548-w london.edu The economics of a pandemic: The case of Covid-19 4 The basics about Covid-19: how it works • Enters through nose, mouth, or eyes. -

Flattening the Curve”

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) WHO Thailand Situation Report – 19 March 2020 Data as reported by the Thai Ministry of Public Health on 19 March 2020 HIGHLIGHTS THAILAND SITUATION • On the 19th of March 2020, 60 new cases of laboratory-confirmed COVID- IN NUMBERS 19 were announced by the Ministry of Public Health of Thailand (MoPH), total and new cases in bringing the total number of cases in Thailand to 272. last 24 hours • The new cases announced today include 12 cases related to drinking 272 confirmed (60 new) venue clusters (57 total cases to date) and 14 cases related to boxing 1 death, 3 severe cases stadium clusters (52 total cases to date). These cases include 3,572 persons under waiters/waitresses, managerial staff, spectators and relatives. Investigation / treatment • Twelve new cases are close contacts of other previously reported cases, five cases are related to attendance at a religious event in Malaysia, 13 cases are related to travel or contact with travelers, while four cases are still under investigation. • Of the 272 COVID-19 cases reported in Thailand, 42 have recovered, 229 are receiving treatment in healthcare settings and one has died. • There is now a cumulative total of 8,157 Patients Under Investigation (PUIs) in Thailand since the COVID- 19 outbreak began, including 3,572 people being actively investigated or treated. This group includes people being treated for other conditions who are no longer suspected of having COVID-19 infection. • Thailand has announced it will join the WHO Solidarity trial, a multi-country clinical study for potential treatments for Covid-19, part of a rapid global search for drugs to treat COVID-19. -

ACHD Flattening the Curve COVID-19

FLATTENING THE CURVE: Mitigation Strategies to Lessen the Impact of COVID-19 Rev. 3/12/20 Moving From Containment to Mitigation Based on the current spread of COVID-19 and the shift from containment (i.e. preventing the novel coronavirus from entering a community) to mitigation (i.e. lessening the impact of the novel coronavirus), it is important to introduce social distancing measures. These measures will help ensure that everybody comes into close contact with fewer people each day, thus slowing the transmission of COVID-19. This slowed transmission is essential for saving lives. Implementing social distancing measures before the virus has gained a strong foothold in a community makes them more effective. In public health, we refer to these measures as “flattening the curve.” Flattening the curve refers to the idea that in an ideal outbreak situation, there would not be more people who are sick than the healthcare system could treat at any one time. If COVID-19 spreads quickly throughout our community and many people are ill at the same time, the healthcare system will not be able to provide all the life sustaining measures required to help all those who are seriously ill (see the blue curve in the graph below). A slower spread of the illness through our community over a longer period of time will reduce the amount of people who are seriously ill at any given time thus putting less strain on our healthcare system that has finite resources (see yellow curve below). WHAT YOU CAN DO NOW Social distancing measures may see extreme, particularly before the virus is spreading in our community, but putting these measures in place will result in fewer deaths and severe illness due to COVID-19.