Atomic Theory & the Periodic Table

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neutron Stars

Chandra X-Ray Observatory X-Ray Astronomy Field Guide Neutron Stars Ordinary matter, or the stuff we and everything around us is made of, consists largely of empty space. Even a rock is mostly empty space. This is because matter is made of atoms. An atom is a cloud of electrons orbiting around a nucleus composed of protons and neutrons. The nucleus contains more than 99.9 percent of the mass of an atom, yet it has a diameter of only 1/100,000 that of the electron cloud. The electrons themselves take up little space, but the pattern of their orbit defines the size of the atom, which is therefore 99.9999999999999% Chandra Image of Vela Pulsar open space! (NASA/PSU/G.Pavlov et al. What we perceive as painfully solid when we bump against a rock is really a hurly-burly of electrons moving through empty space so fast that we can't see—or feel—the emptiness. What would matter look like if it weren't empty, if we could crush the electron cloud down to the size of the nucleus? Suppose we could generate a force strong enough to crush all the emptiness out of a rock roughly the size of a football stadium. The rock would be squeezed down to the size of a grain of sand and would still weigh 4 million tons! Such extreme forces occur in nature when the central part of a massive star collapses to form a neutron star. The atoms are crushed completely, and the electrons are jammed inside the protons to form a star composed almost entirely of neutrons. -

The Periodic Electronegativity Table

The Periodic Electronegativity Table Jan C. A. Boeyens Unit for Advanced Study, University of Pretoria, South Africa Reprint requests to J. C. A. Boeyens. E-mail: [email protected] Z. Naturforsch. 2008, 63b, 199 – 209; received October 16, 2007 The origins and development of the electronegativity concept as an empirical construct are briefly examined, emphasizing the confusion that exists over the appropriate units in which to express this quantity. It is shown how to relate the most reliable of the empirical scales to the theoretical definition of electronegativity in terms of the quantum potential and ionization radius of the atomic valence state. The theory reflects not only the periodicity of the empirical scales, but also accounts for the related thermochemical data and serves as a basis for the calculation of interatomic interaction within molecules. The intuitive theory that relates electronegativity to the average of ionization energy and electron affinity is elucidated for the first time and used to estimate the electron affinities of those elements for which no experimental measurement is possible. Key words: Valence State, Quantum Potential, Ionization Radius Introduction electronegative elements used to be distinguished tra- ditionally [1]. Electronegativity, apart from being the most useful This theoretical notion, in one form or the other, has theoretical concept that guides the practising chemist, survived into the present, where, as will be shown, it is also the most bothersome to quantify from first prin- provides a precise definition of electronegativity. Elec- ciples. In historical context the concept developed in a tronegativity scales that fail to reflect the periodicity of natural way from the early distinction between antag- the L-M curve will be considered inappropriate. -

An Alternate Graphical Representation of Periodic Table of Chemical Elements Mohd Abubakr1, Microsoft India (R&D) Pvt

An Alternate Graphical Representation of Periodic table of Chemical Elements Mohd Abubakr1, Microsoft India (R&D) Pvt. Ltd, Hyderabad, India. [email protected] Abstract Periodic table of chemical elements symbolizes an elegant graphical representation of symmetry at atomic level and provides an overview on arrangement of electrons. It started merely as tabular representation of chemical elements, later got strengthened with quantum mechanical description of atomic structure and recent studies have revealed that periodic table can be formulated using SO(4,2) SU(2) group. IUPAC, the governing body in Chemistry, doesn‟t approve any periodic table as a standard periodic table. The only specific recommendation provided by IUPAC is that the periodic table should follow the 1 to 18 group numbering. In this technical paper, we describe a new graphical representation of periodic table, referred as „Circular form of Periodic table‟. The advantages of circular form of periodic table over other representations are discussed along with a brief discussion on history of periodic tables. 1. Introduction The profoundness of inherent symmetry in nature can be seen at different depths of atomic scales. Periodic table symbolizes one such elegant symmetry existing within the atomic structure of chemical elements. This so called „symmetry‟ within the atomic structures has been widely studied from different prospects and over the last hundreds years more than 700 different graphical representations of Periodic tables have emerged [1]. Each graphical representation of chemical elements attempted to portray certain symmetries in form of columns, rows, spirals, dimensions etc. Out of all the graphical representations, the rectangular form of periodic table (also referred as Long form of periodic table or Modern periodic table) has gained wide acceptance. -

The Development of the Periodic Table and Its Consequences Citation: J

Firenze University Press www.fupress.com/substantia The Development of the Periodic Table and its Consequences Citation: J. Emsley (2019) The Devel- opment of the Periodic Table and its Consequences. Substantia 3(2) Suppl. 5: 15-27. doi: 10.13128/Substantia-297 John Emsley Copyright: © 2019 J. Emsley. This is Alameda Lodge, 23a Alameda Road, Ampthill, MK45 2LA, UK an open access, peer-reviewed article E-mail: [email protected] published by Firenze University Press (http://www.fupress.com/substantia) and distributed under the terms of the Abstract. Chemistry is fortunate among the sciences in having an icon that is instant- Creative Commons Attribution License, ly recognisable around the world: the periodic table. The United Nations has deemed which permits unrestricted use, distri- 2019 to be the International Year of the Periodic Table, in commemoration of the 150th bution, and reproduction in any medi- anniversary of the first paper in which it appeared. That had been written by a Russian um, provided the original author and chemist, Dmitri Mendeleev, and was published in May 1869. Since then, there have source are credited. been many versions of the table, but one format has come to be the most widely used Data Availability Statement: All rel- and is to be seen everywhere. The route to this preferred form of the table makes an evant data are within the paper and its interesting story. Supporting Information files. Keywords. Periodic table, Mendeleev, Newlands, Deming, Seaborg. Competing Interests: The Author(s) declare(s) no conflict of interest. INTRODUCTION There are hundreds of periodic tables but the one that is widely repro- duced has the approval of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and is shown in Fig.1. -

The Periodic Table of Elements

The Periodic Table of Elements 1 2 6 Atomic Number = Number of Protons = Number of Electrons HYDROGENH HELIUMHe 1 Chemical Symbol NON-METALS 4 3 4 C 5 6 7 8 9 10 Li Be CARBON Chemical Name B C N O F Ne LITHIUM BERYLLIUM = Number of Protons + Number of Neutrons* BORON CARBON NITROGEN OXYGEN FLUORINE NEON 7 9 12 Atomic Weight 11 12 14 16 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 SODIUMNa MAGNESIUMMg ALUMINUMAl SILICONSi PHOSPHORUSP SULFURS CHLORINECl ARGONAr 23 24 METALS 27 28 31 32 35 40 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 POTASSIUMK CALCIUMCa SCANDIUMSc TITANIUMTi VANADIUMV CHROMIUMCr MANGANESEMn FeIRON COBALTCo NICKELNi CuCOPPER ZnZINC GALLIUMGa GERMANIUMGe ARSENICAs SELENIUMSe BROMINEBr KRYPTONKr 39 40 45 48 51 52 55 56 59 59 64 65 70 73 75 79 80 84 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 RUBIDIUMRb STRONTIUMSr YTTRIUMY ZIRCONIUMZr NIOBIUMNb MOLYBDENUMMo TECHNETIUMTc RUTHENIUMRu RHODIUMRh PALLADIUMPd AgSILVER CADMIUMCd INDIUMIn SnTIN ANTIMONYSb TELLURIUMTe IODINEI XeXENON 85 88 89 91 93 96 98 101 103 106 108 112 115 119 122 128 127 131 55 56 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 CESIUMCs BARIUMBa HAFNIUMHf TANTALUMTa TUNGSTENW RHENIUMRe OSMIUMOs IRIDIUMIr PLATINUMPt AuGOLD MERCURYHg THALLIUMTl PbLEAD BISMUTHBi POLONIUMPo ASTATINEAt RnRADON 133 137 178 181 184 186 190 192 195 197 201 204 207 209 209 210 222 87 88 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 FRANCIUMFr RADIUMRa RUTHERFORDIUMRf DUBNIUMDb SEABORGIUMSg BOHRIUMBh HASSIUMHs MEITNERIUMMt DARMSTADTIUMDs ROENTGENIUMRg COPERNICIUMCn NIHONIUMNh -

TEK 8.5C: Periodic Table

Name: Teacher: Pd. Date: TEK 8.5C: Periodic Table TEK 8.5C: Interpret the arrangement of the Periodic Table, including groups and periods, to explain how properties are used to classify elements. Elements and the Periodic Table An element is a substance that cannot be separated into simpler substances by physical or chemical means. An element is already in its simplest form. The smallest piece of an element that still has the properties of that element is called an atom. An element is a pure substance, containing only one kind of atom. The Periodic Table of Elements is a list of all the elements that have been discovered and named, with each element listed in its own element square. Elements are represented on the Periodic Table by a one or two letter symbol, and its name, atomic number and atomic mass. The Periodic Table & Atomic Structure The elements are listed on the Periodic Table in atomic number order, starting at the upper left corner and then moving from the left to right and top to bottom, just as the words of a paragraph are read. The element’s atomic number is based on the number of protons in each atom of that element. In electrically neutral atoms, the atomic number also represents the number of electrons in each atom of that element. For example, the atomic number for neon (Ne) is 10, which means that each atom of neon has 10 protons and 10 electrons. Magnesium (Mg) has an atomic number of 12, which means it has 12 protons and 12 electrons. -

Llfltfits Paul Stanek, MST-6

COAJF- 9 50cDo/-~^0 LA-UR- 9 5-1666 Title: AGE HARDENING IN RAPIDLY SOLIDIFIED AND HOT ISOSTATICALLY PRESSED BERYLLIUM-ALUM1UM SILVER ALLOYS HVAUli Author(s): David H. Carter, MST-6 Andrew McGeorge, MST-6 Loren A. Jacobson, MST-6 llfltfits Paul Stanek, MST-6 IflllS,Ic 8-o° ,S8 si Proceedings of TMS Annual Meeting, Las Vegas, jJffilJSif—- Nevada, February 1995 as-IVUiS' i in Los Alamos NATIONAL LABORATORY Los Alamos National Laboratory, an affirmative action/equal opportunity employer, is operated by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy under contract W-7405-ENG-36. By acceptance of this article, the publisher recognizes that the U.S. Government retains a nonexclusive, royalty-free license to publish or reproduce the published form of this contribution, or to allow others to do so, for U.S. Government purposes. The Los Alamos National Laboratory requests that the publisher identify this article as work performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy* FotmNo.B36R5 MCTOIQimnM f\c mie hAMMr&T 10 i mi in ST26291M1 DISCLAIMER Portions of this document may be illegible in electronic image products. Images are produced from the best available original document. Age Hardening in Rapidly Solidified and Hot Isostatically Pressed Beryllium-Aluminum-Silver Alloys David H. Carter, Andrew C. McGeorge,* Loren A. Jacobson, and Paul W. Stanek Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos NM 87545 Abstract Three different alloys of beryllium, aluminum and silver were processed to powder by centrifugal atomization in a helium atmosphere. Alloy com• positions were, by weight, 50% Be, 47.5% Al, 2.5% Ag, 50% Be, 47% Al, 3% Ag, and 50% Be, 46% Al, 4% Ag. -

Centripetal Force Is Balanced by the Circular Motion of the Elctron Causing the Centrifugal Force

STANDARD SC1 b. Construct an argument to support the claim that the proton (and not the neutron or electron) defines the element’s identity. c. Construct an explanation based on scientific evidence of the production of elements heavier than hydrogen by nuclear fusion. d. Construct an explanation that relates the relative abundance of isotopes of a particular element to the atomic mass of the element. First, we quickly review pre-requisite concepts One of the most curious observations with atoms is the fact that there are charged particles inside the atom and there is also constant spinning and Warm-up 1: List the name, charge, mass, and location of the three subatomic circling. How does atom remain stable under these conditions? Remember particles Opposite charges attract each other; Like charges repel each other. Your Particle Location Charge Mass in a.m.u. Task: Read the following information and consult with your teacher as STABILITY OF ATOMS needed, answer Warm-Up tasks 2 and 3 on Page 2. (3) Death spiral does not occur at all! This is because the centripetal force is balanced by the circular motion of the elctron causing the centrifugal force. The centrifugal force is the outward force from the center to the circumference of the circle. Electrons not only spin on their own axis, they are also in a constant circular motion around the nucleus. Despite this terrific movement, electrons are very stable. The stability of electrons mainly comes from the electrostatic forces of attraction between the nucleus and the electrons. The electrostatic forces are also known as Coulombic Forces of Attraction. -

Of the Periodic Table

of the Periodic Table teacher notes Give your students a visual introduction to the families of the periodic table! This product includes eight mini- posters, one for each of the element families on the main group of the periodic table: Alkali Metals, Alkaline Earth Metals, Boron/Aluminum Group (Icosagens), Carbon Group (Crystallogens), Nitrogen Group (Pnictogens), Oxygen Group (Chalcogens), Halogens, and Noble Gases. The mini-posters give overview information about the family as well as a visual of where on the periodic table the family is located and a diagram of an atom of that family highlighting the number of valence electrons. Also included is the student packet, which is broken into the eight families and asks for specific information that students will find on the mini-posters. The students are also directed to color each family with a specific color on the blank graphic organizer at the end of their packet and they go to the fantastic interactive table at www.periodictable.com to learn even more about the elements in each family. Furthermore, there is a section for students to conduct their own research on the element of hydrogen, which does not belong to a family. When I use this activity, I print two of each mini-poster in color (pages 8 through 15 of this file), laminate them, and lay them on a big table. I have students work in partners to read about each family, one at a time, and complete that section of the student packet (pages 16 through 21 of this file). When they finish, they bring the mini-poster back to the table for another group to use. -

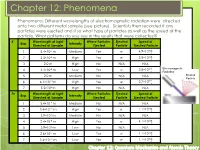

Chapter 12: Phenomena

Chapter 12: Phenomena Phenomena: Different wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation were directed onto two different metal sample (see picture). Scientists then recorded if any particles were ejected and if so what type of particles as well as the speed of the particle. What patterns do you see in the results that were collected? K Wavelength of Light Where Particles Ejected Speed of Exp. Intensity Directed at Sample Ejected Particle Ejected Particle -7 - 4 푚 1 5.4×10 m Medium Yes e 4.9×10 푠 -8 - 6 푚 2 3.3×10 m High Yes e 3.5×10 푠 3 2.0 m High No N/A N/A 4 3.3×10-8 m Low Yes e- 3.5×106 푚 Electromagnetic 푠 Radiation 5 2.0 m Medium No N/A N/A Ejected Particle -12 - 8 푚 6 6.1×10 m High Yes e 2.7×10 푠 7 5.5×104 m High No N/A N/A Fe Wavelength of Light Where Particles Ejected Speed of Exp. Intensity Directed at Sample Ejected Particle Ejected Particle 1 5.4×10-7 m Medium No N/A N/A -11 - 8 푚 2 3.4×10 m High Yes e 1.1×10 푠 3 3.9×103 m Medium No N/A N/A -8 - 6 푚 4 2.4×10 m High Yes e 4.1×10 푠 5 3.9×103 m Low No N/A N/A -7 - 5 푚 6 2.6×10 m Low Yes e 1.1×10 푠 -11 - 8 푚 7 3.4×10 m Low Yes e 1.1×10 푠 Chapter 12: Quantum Mechanics and Atomic Theory Chapter 12: Quantum Mechanics and Atomic Theory o Electromagnetic Radiation o Quantum Theory o Particle in a Box Big Idea: The structure of atoms o The Hydrogen Atom must be explained o Quantum Numbers using quantum o Orbitals mechanics, a theory in o Many-Electron Atoms which the properties of particles and waves o Periodic Trends merge together. -

Introduction to Chemistry

Introduction to Chemistry Author: Tracy Poulsen Digital Proofer Supported by CK-12 Foundation CK-12 Foundation is a non-profit organization with a mission to reduce the cost of textbook Introduction to Chem... materials for the K-12 market both in the U.S. and worldwide. Using an open-content, web-based Authored by Tracy Poulsen collaborative model termed the “FlexBook,” CK-12 intends to pioneer the generation and 8.5" x 11.0" (21.59 x 27.94 cm) distribution of high-quality educational content that will serve both as core text as well as provide Black & White on White paper an adaptive environment for learning. 250 pages ISBN-13: 9781478298601 Copyright © 2010, CK-12 Foundation, www.ck12.org ISBN-10: 147829860X Except as otherwise noted, all CK-12 Content (including CK-12 Curriculum Material) is made Please carefully review your Digital Proof download for formatting, available to Users in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution/Non-Commercial/Share grammar, and design issues that may need to be corrected. Alike 3.0 Unported (CC-by-NC-SA) License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- sa/3.0/), as amended and updated by Creative Commons from time to time (the “CC License”), We recommend that you review your book three times, with each time focusing on a different aspect. which is incorporated herein by this reference. Specific details can be found at http://about.ck12.org/terms. Check the format, including headers, footers, page 1 numbers, spacing, table of contents, and index. 2 Review any images or graphics and captions if applicable. -

Heavy Metals'' with ``Potentially Toxic Elements'

It’s Time to Replace the Term “Heavy Metals” with “Potentially Toxic Elements” When Reporting Environmental Research Olivier Pourret, Andrew Hursthouse To cite this version: Olivier Pourret, Andrew Hursthouse. It’s Time to Replace the Term “Heavy Metals” with “Potentially Toxic Elements” When Reporting Environmental Research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, MDPI, 2019, 16 (22), pp.4446. 10.3390/ijerph16224446. hal-02889766 HAL Id: hal-02889766 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02889766 Submitted on 5 Jul 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Letter It’s Time to Replace the Term “Heavy Metals” with “Potentially Toxic Elements” When Reporting Environmental Research Olivier Pourret 1,* and Andrew Hursthouse 2,* 1 UniLaSalle, AGHYLE, 19 rue Pierre Waguet, 60000 Beauvais, France 2 School of Computing, Engineering & Physical Sciences, University of the West of Scotland, Paisley PA1 2BE, UK * Correspondence: [email protected] (O.P.); [email protected] (A.H.) Received: 28 October 2019; Accepted: 12 November 2019; Published: date Abstract: Even if the Periodic Table of Chemical Elements is relatively well defined, some controversial terms are still in use.