Keiretsu, Competition, and Market Access

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustainability Report 2015 Report Sustainability (April 2014–March 2015) 2014–March (April

Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation http://www.nssmc.com/en/ NSSMC’s Logotype Sustainability Report 2015 (April 2014–March 2015) The central triangle in the logo represents a blast furnace and the people who create steel. It symbolizes steel, indispensable to the advance- ment of civilization, brightening all corners of the world. The center point can be viewed as a summit, reflecting our strong will to become the world’s leading steelmaker. It can also be viewed as depth, with the vanishing point rep- resenting the unlimited future potential of steel as a material. The cobalt blue and sky blue color palette represents innovation and reliability. Image provided by Toyota Motor Corporation Image provided by East Japan Railway Company Image provided by Yamaha Motor Co., Ltd. Image provided by Yamaha Motor Co., Ltd. Sustainability Report ecoPROCESSecoecoPROCESSPROCESS ecoPRODUCTSecoPRODUCTSecoPRODUCTS ecoSOLUTIONecoSOLUTIONecoSOLUTION NSSMC and its printing service support Green Procurement Initiatives. Eco-friendly vegetable oil ink is used Printed in Japan for this report. +++ 革新的な技術の開発革新的な技術の開発革新的な技術の開発 eco PROCESSecoPROCESSecoPROCESS ecoPRODUCTSecoPRODUCTSecoPRODUCTS ecoSOLUTIONecoSOLUTIONecoSOLUTION NIPPON STEEL & SUMITOMO METAL CORPORATION Sustainability Report 2015 01 Corporate Philosophy Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation Group will pursue world-leading technologies and manufacturing capabilities, and contribute to society by providing excellent products and services. Structure of the Report Management Principles Editorial policy This Sustainability Report is the 18th since the former 1. We continue to emphasize the importance of integrity and reliability in our actions. Nippon Steel Corporation issued what is the first sus- 2. We provide products and services that benefit society, and grow in partnership with our customers. NSSMC’s Businesses tainability report by a Japanese steel manufacturer, in 3. -

Foreign Direct Investment and Keiretsu: Rethinking U.S. and Japanese Policy

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: The Effects of U.S. Trade Protection and Promotion Policies Volume Author/Editor: Robert C. Feenstra, editor Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-23951-9 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/feen97-1 Conference Date: October 6-7, 1995 Publication Date: January 1997 Chapter Title: Foreign Direct Investment and Keiretsu: Rethinking U.S. and Japanese Policy Chapter Author: David E. Weinstein Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c0310 Chapter pages in book: (p. 81 - 116) 4 Foreign Direct Investment and Keiretsu: Rethinking U.S. and Japanese Policy David E. Weinstein For twenty-five years, the U.S. and Japanese governments have seen the rise of corporate groups in Japan, keiretsu, as due in part to foreign pressure to liberal- ize the Japanese market. In fact, virtually all works that discuss barriers in a historical context argue that Japanese corporations acted to insulate themselves from foreign takeovers by privately placing shares with each other (See, e.g., Encarnation 1992,76; Mason 1992; and Lawrence 1993). The story has proved to be a major boon for the opponents of a neoclassical approach to trade and investment policy. Proponents of the notion of “Japanese-style capitalism” in the Japanese government can argue that they did their part for liberalization and cannot be held responsible for private-sector outcomes. Meanwhile, pro- ponents of results-oriented policies (ROPs) can point to yet another example of how the removal of one barrier led to the formation of a second barrier. -

Sumitomo Corporation's Dirty Energy Trade

SUMITOMO CORPORATION’S DIRTY ENERGY TRADE Biomass, Coal and Japan’s Energy Future DECEMBER 2019 SUMITOMO CORPORATION’S DIRTY ENERGY TRADE Biomass, Coal and Japan’s Energy Future CONTRIBUTORS Authors: Roger Smith, Jessie Mannisto, Ryan Cunningham of Mighty Earth Translation: EcoNetworks Co. Design: Cecily Anderson, anagramdesignstudio.com Any errors or inaccuracies remain the responsibility of Mighty Earth. 2 © Jan-Joseph Stok / Greenpeace CONTENTS 4 Introduction 7 Japan’s Embrace of Dirty Energy 7 Coal vs the Climate 11 Biomass Burning: Missing the Forest for the Trees 22 Sumitomo Corporation’s Coal Business: Unrepentant Polluter 22 Feeding Japan’s Coal Reliance 23 Building Dirty Power Plants Abroad and at Home 27 Sumitomo Corporation, climate laggard 29 Sumitomo Corporation’s Biomass Business: Trashing Forests for Fuel 29 Global Forests at Risk 34 Sumitomo and Southeastern Forests 39 Canadian Wood Pellet Production 42 Vietnam 44 Sumitomo Corporation and Japanese Biomass Power Plants 47 Sumitomo Corporation and You 47 TBC Corporation 49 National Tire Wholesale 50 Sumitomo Corporation: Needed Policy Changes 3 Wetland forest logging tied to Enviva’s biomass plant in Southampton, North Carolina. Dogwood Alliance INTRODUCTION SUMITOMO CORPORATION’S DIRTY ENERGY TRADE—AND ITS OPPORTUNITY TO CHANGE While the rest of the developed world accelerates its deployment of clean, renewable energy, Japan is running backwards. It is putting in place policies which double down on its reliance on coal, and indiscriminately subsidize biomass power technologies that accelerate climate change. Government policy is not the only driver of Japan’s dirty energy expansion – the private sector also plays a pivotal role in growing the country’s energy carbon footprint. -

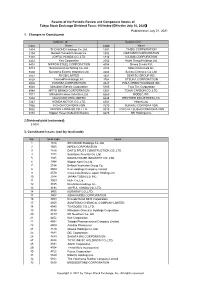

Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents 2

Results of the Periodic Review and Component Stocks of Tokyo Stock Exchange Dividend Focus 100 Index (Effective July 30, 2021) Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents Addition(18) Deletion(18) CodeName Code Name 1414SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 1801 TAISEI CORPORATION 2154BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 1802 OBAYASHI CORPORATION 3191JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. 1812 KAJIMA CORPORATION 4452Kao Corporation 2502 Asahi Group Holdings,Ltd. 5401NIPPON STEEL CORPORATION 4004 Showa Denko K.K. 5713Sumitomo Metal Mining Co.,Ltd. 4183 Mitsui Chemicals,Inc. 5802Sumitomo Electric Industries,Ltd. 4204 Sekisui Chemical Co.,Ltd. 5851RYOBI LIMITED 4324 DENTSU GROUP INC. 6028TechnoPro Holdings,Inc. 4768 OTSUKA CORPORATION 6502TOSHIBA CORPORATION 4927 POLA ORBIS HOLDINGS INC. 6503Mitsubishi Electric Corporation 5105 Toyo Tire Corporation 6988NITTO DENKO CORPORATION 5301 TOKAI CARBON CO.,LTD. 7011Mitsubishi Heavy Industries,Ltd. 6269 MODEC,INC. 7202ISUZU MOTORS LIMITED 6448 BROTHER INDUSTRIES,LTD. 7267HONDA MOTOR CO.,LTD. 6501 Hitachi,Ltd. 7956PIGEON CORPORATION 7270 SUBARU CORPORATION 9062NIPPON EXPRESS CO.,LTD. 8015 TOYOTA TSUSHO CORPORATION 9101Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha 8473 SBI Holdings,Inc. 2.Dividend yield (estimated) 3.50% 3. Constituent Issues (sort by local code) No. local code name 1 1414 SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 2 1605 INPEX CORPORATION 3 1878 DAITO TRUST CONSTRUCTION CO.,LTD. 4 1911 Sumitomo Forestry Co.,Ltd. 5 1925 DAIWA HOUSE INDUSTRY CO.,LTD. 6 1954 Nippon Koei Co.,Ltd. 7 2154 BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 8 2503 Kirin Holdings Company,Limited 9 2579 Coca-Cola Bottlers Japan Holdings Inc. 10 2914 JAPAN TOBACCO INC. 11 3003 Hulic Co.,Ltd. 12 3105 Nisshinbo Holdings Inc. 13 3191 JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. -

World's First Mass Production of Difficult-To-Form Automotive Body

May 18, 2018 World’s First Mass Production of Difficult-to-Form Automotive Body Structural Parts Using Super High Formability 980MPa Ultra High Tensile Steel - Contributing to Reduction in Body Weight of Nissan’s New Crossover - Company name: Unipres Corporation Representative: Masanobu Yoshizawa, President and Representative Director Securities code: 5949 (Tokyo Stock Exchange, First Section) Contact: Yoshio Ito, Executive Vice President Tel. +81-45-470-8755 Website: https://www.unipres.co.jp/ UNIPRES CORPORATION (Head Office: Yokohama, Kanagawa Pref., Japan; President: Masanobu Yoshizawa; hereinafter “UNIPRES”) has succeeded in the world’s first mass production of difficult-to-form car body structural parts using super high formability 980MPa (megapascal) ultra high tensile strength steel(hereinafter SHF 980MPa steel) and began supplying parts for Nissan Motor Co., Ltd.’s luxury mid-size Crossover launched in the North American market in 2018. Across the automobile industry in recent years, while weight saving of car body has been advanced due to growing demand for reductions in CO2 emissions (improving fuel efficiency) in light of preserving the global environment, higher car body strength is also desired for greater occupant protection in the event of a collision. As a result, automobile manufacturers have accelerated the use of ultra high tensile strength steel that enhances weight saving and collision safety through thickness reduction and greater strength of materials. The SHF 980MPa steel that is used for those parts ordered by Nissan Motor Co., Ltd., this time, is a new material developed by Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation, and is applied to front side members, rear side members, and other under-body structural parts that are difficult to form. -

Keiretsu Divergence in the Japanese Automotive Industry Akira Takeishi, Yoshihisa Noro

Keiretsu Divergence in the Japanese Automotive Industry Akira Takeishi, Yoshihisa Noro To cite this version: Akira Takeishi, Yoshihisa Noro. Keiretsu Divergence in the Japanese Automotive Industry: Why Have Some, But Not All, Gone?. 2017. hal-02952225 HAL Id: hal-02952225 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02952225 Preprint submitted on 29 Sep 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - ShareAlike| 4.0 International License CEAFJP Discussion Paper Series 17-04 CEAFJPDP Keiretsu Divergence in the Japanese Automotive Industry: Why Have Some, But Not All, Gone? Akira Takeishi Graduate School of Economics, Kyoto University CEAFJP Visiting Researcher Yoshihisa Noro Mitsubishi Research Institute, Inc. August 2017 http://ffj.ehess.fr KEIRETSU DIVERGENCE IN THE JAPANESE AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY: WHY HAVE SOME, BUT NOT ALL, GONE? August 2, 2017 Akira Takeishi Graduate School of Economics, Kyoto University; Visiting Researcher (October 2015- July 2016), Fondation France-Japon de l’École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales e-mail address: [email protected] Yoshihisa Noro Mitsubishi Research Institute, Inc. ABSTRACT The keiretsu relationship in the Japanese automotive industry was once admired as a source of competitive advantage. -

Business Groups, Networks, and Embeddedness: Innovation and Implementation Alliances in Japanese Electronics, 1985–1998

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title Business groups, networks, and embeddedness: innovation and implementation alliances in Japanese electronics, 1985–1998 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3dq9f64q Journal Industrial and Corporate Change, 26(3) Authors Lincoln, James R Guillot, Didier Sargent, Matthew Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Industrial and Corporate Change Advance Access published September 10, 2016 Industrial and Corporate Change, 2016, 1–22 doi: 10.1093/icc/dtw037 Original article Business groups, networks, and embeddedness: innovation and implementation alliances in Japanese electronics, 1985–1998 James R. Lincoln,1,* Didier Guillot,2 and Matthew Sargent3 1Walter A. Haas School of Business, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA. e-mail: [email protected], 2Fukui Prefectural University, Fukui 910-1195, Japan. e-mail: [email protected] Downloaded from and 3USC Digital Humanities Program, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089, USA. e-mail: [email protected] *Main author for correspondence. http://icc.oxfordjournals.org/ Abstract This paper examines the changing process of strategic alliance formation in the Japanese electronics industry between 1985 and 1998. With data on 123–135 Japanese electronics/electrical machinery makers, we use a dyad panel regression methodology to address hypotheses drawn largely from em- beddedness theory on how the firms’ horizontal and vertical keiretsu business group affiliations and prior alliance networks supported and constrained partner choice in new R&D (innovation) and nonR&D (implementation) domestic economy alliances. We find that in the first half of our series (1985–1991; the “preburst” period), keiretsu served as infrastructure for new strategic alliances that by guest on September 11, 2016 had both innovation (R&D) and implementation (nonR&D) goals. -

JP Morgan and the Money Trust

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF ST. LOUIS ECONOMIC EDUCATION The Panic of 1907: J.P. Morgan and the Money Trust Lesson Author Mary Fuchs Standards and Benchmarks (see page 47) Lesson Description The Panic of 1907 was a financial crisis set off by a series of bad banking decisions and a frenzy of withdrawals caused by public distrust of the banking system. J.P. Morgan, along with other wealthy Wall Street bankers, loaned their own funds to save the coun- try from a severe financial crisis. But what happens when a single man, or small group of men, have the power to control the finances of a country? In this lesson, students will learn about the Panic of 1907 and the measures Morgan used to finance and save the major banks and trust companies. Students will also practice close reading to analyze texts from the Pujo hearings, newspapers, and reactionary articles to develop an evidence- based argument about whether or not a money trust—a Morgan-led cartel—existed. Grade Level 10-12 Concepts Bank run Bank panic Cartel Central bank Liquidity Money trust Monopoly Sherman Antitrust Act Trust ©2015, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Permission is granted to reprint or photocopy this lesson in its entirety for educational purposes, provided the user credits the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, www.stlouisfed.org/education. 1 Lesson Plan The Panic of 1907: J.P. Morgan and the Money Trust Time Required 100-120 minutes Compelling Question What did J.P. Morgan have to do with the founding of the Federal Reserve? Objectives Students will • define bank run, bank panic, monopoly, central bank, cartel, and liquidity; • explain the Panic of 1907 and the events leading up to the panic; • analyze the Sherman Antitrust Act; • explain how monopolies worked in the early 20th-century banking industry; • develop an evidence-based argument about whether or not a money trust—a Morgan-led cartel—existed • explain how J.P. -

International Trading Companies: Building on the Japanese Model Robert W

Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business Volume 4 Issue 2 Fall Fall 1982 International Trading Companies: Building on the Japanese Model Robert W. Dziubla Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njilb Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert W. Dziubla, International Trading Companies: Building on the Japanese Model, 4 Nw. J. Int'l L. & Bus. 422 (1982) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business International Trading Companies: Building On The Japanese Model Robert W. Dziubla* Passageof the Export Trading Company Act of 1982provides new op- portunitiesfor American business to organize and operate general trading companies. Afterpresenting a thorough history and description of the Japa- nese sogoshosha, Mr. Dziubla gives several compelling reasonsfor Ameri- cans to establish export trading companies. He also examines the changes in United States banking and antitrust laws that have resultedfrom passage of the act, and offers suggestionsfor draftingguidelines, rules, and regula- tionsfor the Export Trading Company Act. For several years, American legislators and businessmen have warned that if America is to balance its international trade-and in particular offset the cost of importing billions of dollars worth of oil- she must take concrete steps to increase her exporting capabilities., On October 8, 1982, the United States took just such a step when President Reagan signed into law the Export Trading Company Act of 1982,2 which provides for the development of international general trading companies similar to the ones used so successfully by the Japanese. -

Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group CSR Report Digest Version

Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group CSR Report Digest version www.smfg.co.jp/english Today, Tomorrow and Beyond First,First, I wouldwould likelike toto extendextend ourour deepestdeepest sympathiessympathies andand heartfeltheartfelt condolencescondolences toto allall thosethose whowho havehave sufferedsuffered andand INDEX toto tthehe ffamiliesamilies andand ffriendsriends ooff tthosehose wwhoho ttragicallyragically llostost ttheirheir llivesives iinn thethe devastatingdevastating earthquakeearthquake andand tsunamitsunami Foreword 1 thatthat struckstruck northeasternnortheastern JapanJapan onon MarchMarch 11,11, 2011.2011. WeWe praypray forfor thethe earlyearly recoveryrecovery ofof thethe affectedaffected peoplepeople andand areas.areas. Commitment from the Top 3 A Conversation with Tadao Ando, SMFGSMFG isis dedicateddedicated toto seamlesslyseamlessly respondingresponding toto clients’clients’ needsneeds byby leveragingleveraging ourour group-widegroup-wide capabilities,capabilities, Takeshi Kunibe and Koichi Miyata What can we do now to spur the reconstruction and revitalization of Japan, offeringoffering optimaloptimal pproductsroducts aandnd sservices,ervices, aandnd eensuringnsuring tthathat eeveryvery employeeemployee andand thethe overalloverall groupgroup areare capablecapable ofof and help resolve global issues? respondingresponding ttoo tthehe challengeschallenges ooff gglobalization.lobalization. I bbelieveelieve tthathat throughthrough thesethese measures,measures, Measures to Support Reconstruction after the March 11 President -

Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone?

IRLE IRLE WORKING PAPER #188-09 September 2009 Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone? James R. Lincoln, Masahiro Shimotani Cite as: James R. Lincoln, Masahiro Shimotani. (2009). “Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone?” IRLE Working Paper No. 188-09. http://irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/188-09.pdf irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers Institute for Research on Labor and Employment Institute for Research on Labor and Employment Working Paper Series (University of California, Berkeley) Year Paper iirwps-- Whither the Keiretsu, Japan’s Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone? James R. Lincoln Masahiro Shimotani University of California, Berkeley Fukui Prefectural University This paper is posted at the eScholarship Repository, University of California. http://repositories.cdlib.org/iir/iirwps/iirwps-188-09 Copyright c 2009 by the authors. WHITHER THE KEIRETSU, JAPAN’S BUSINESS NETWORKS? How were they structured? What did they do? Why are they gone? James R. Lincoln Walter A. Haas School of Business University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720 USA ([email protected]) Masahiro Shimotani Faculty of Economics Fukui Prefectural University Fukui City, Japan ([email protected]) 1 INTRODUCTION The title of this volume and the papers that fill it concern business “groups,” a term suggesting an identifiable collection of actors (here, firms) within a clear-cut boundary. The Japanese keiretsu have been described in similar terms, yet compared to business groups in other countries the postwar keiretsu warrant the “group” label least. -

Case Studies in Change from the Japanese Automotive Industry

UC Berkeley Working Paper Series Title Keiretsu, Governance, and Learning: Case Studies in Change from the Japanese Automotive Industry Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/43q5m4r3 Authors Ahmadjian, Christina L. Lincoln, James R. Publication Date 2000-05-19 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Institute of Industrial Relations University of California, Berkeley Working Paper No. 76 May 19, 2000 Keiretsu, governance, and learning: Case studies in change from the Japanese automotive industry Christina L. Ahmadjian Graduate School of Business Columbia University New York, NY 10027 (212)854-4417 fax: (212)316-9355 [email protected] James R. Lincoln Walter A. Haas School of Business University of California at Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720 (510) 643-7063 [email protected] We are grateful to Nick Argyres, Bob Cole, Ray Horton, Rita McGrath, Atul Nerkar, Toshi Nishiguchi, Joanne Oxley, Hugh Patrick, Eleanor Westney, and Oliver Williamson for helpful comments. We also acknowledge useful feedback from members of the Sloan Corporate Governance Project at Columbia Law School. Research grants from the Japan – U. S. Friendship Commission, the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and the Clausen Center for International Business and Policy of the Haas School of Business at UC Berkeley are also gratefully acknowledged. Keiretsu, governance, and learning: Case studies in change from the Japanese automotive industry ABSTRACT The “keiretsu” structuring of assembler-supplier relations historically enabled Japanese auto assemblers to remain lean and flexible while enjoying a level of control over supply akin to that of vertical integration. Yet there is much talk currently of breakdown in keiretsu networks.