Building on a Rickety Foundation: “An Evangelical Agenda”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

29Th April 2001

A MOUNTAIN The Australian OUT OF MOW LL’SHI LL CHURCH Deborah Russell n many ways the gospel of spread of the gospel. throughout the 1960s. The Billy Graham I Christ is at the crossroads Mowll placed key people in teaching Crusade was the place where Phillip and “ in our society. Will our and training positions early in his tenure as Peter Jensen, and Robert Forsyth, all nation turn to Christ or continue to turn Archbishop. Foremost among them was possible candidates for archbishop in this its back on him? Clearly it is important T.C. Hammond as principal of Moore election, were converted. RECORD that we elect a Bishop for the Diocese College. Mowll also saved the Church By the time Harry Goodhew was and the Province who will be the right Missionary Society from an untimely elected archbishop in 1993, the Anglican leader at this critical time”. death: refusing to support breakaway ele - church was again struggling to deal with The Bishop of North Sydney, cur - ments in England, he instead gave extra the ever-present conflict between the lib - April 29, 2001 Issue 1883 rently the administrator of the diocese resources and leaders to the CMS in eral and conservative evangelical elements until the new archbishop takes over the Sydney. The Mowlls were also active in in the church. The problem of falling or reins, made these comments as part of an aged care; Mowll Village in Castle Hill’s static church membership and a host of “There was a greater belief from the open letter to Synod members who will Anglican retirement complex bears his other social and spiritual questions con - meet in early June (see part of the letter name in honour of their contribution. -

Communicative Action: a Way Forward For

45 Communicative Action: A Way Forward for InterReligious Dialogue By Brian Douglas Abstract This article explores the theory of communicative action of the philosopher Jurgen Habermas as a way forward for inter‐religious dialogue. Communicative action based on the intersubjectivity, rationality and force of argumentative speech stands in contrast to the boundary marking of hermeneutic idealism. Communicative action distinguishes between the particularity of one’s lifeworld and the universality of a system paradigm. Communicative action is seen as a way for inter‐religious dialogue to explore the importance of various religious traditions. Whilst arguing that communicative action requires an individual to step outside the solipsism of her own lifeworld, this article also acknowledges the importance of an individual’s particular religious interests. Early in 2008, Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury and leader of the worldwide Anglican Communion, made headlines throughout the world following a lecture he delivered at the Royal Courts of Justice in London (Williams 2008a). The Archbishop suggested that aspects of sharia law should be used by Muslims in the United Kingdom to resolve personal and domestic issues such as marriage and property disputes. The Archbishop said he thought that the use of sharia law was an inevitable development in Britain. Media reaction to the Archbishop’s speech was extreme, with some commentators saying that he was giving heart to Muslim terrorists (The Sun 2008). The Archbishop did receive support -

Two Ways Ministries - the First Five Years 2015-2019

Two Ways Ministries - The First Five Years 2015-2019 Two Ways Ministries has developed a network of the next generation of Christians who plan to live boldly and single mindedly for Christ, while Phillip has continued to engage in and demonstrate evangelistic preaching in Australia and overseas. To live is Christ and to die is gain Two Ways Ministries Preaching the gospel by teaching the Bible Our Programs and Preaching Three Programs and Preaching Trajectory weekends Queen’s Birthday Conferences • 413 different people attended one of the 15 • Two Ways Ministries Launch was May 2015 Trajectory conferences, over the last four • From 2016– 2019 we ran four Queen’s years. Some have attended every year. Birthday Conferences and an extra conference • Our weekend topics have included Thorns and in November 2017. Thistles, Avoiding the Spirit in the Work of the Spirit and Rejoice in Youth. Phillip’s Public Preaching Over the last five years Phillip has crisscrossed Forums both Australia, but mainly Sydney, preaching in • 681 different people have attended one of our churches, universities, colleges and schools. He regular Forums. These run twice a week, has spoken at numerous conferences for students, Thursday and Friday for about six months families, clergy and congregations. annually. His overseas speaking tours have taken him to • From 2016 – 2019 we’ve covered three broad • 2015 Dubai, England, Scotland, South topics all related to evangelism and involving Africa and Singapore Two Ways to Live: • 2016 USA o The gospel According to David (Psalms) • 2018 Malaysia, New Zealand o Evangelism in a Post Christian World • 2018-19 Dubai, UK, Singapore o Worldview Evangelism • 2019 Argentina and Chile • Over five years we’ve covered 46 topics. -

16Th December 1985

Introducing Kippy Koala JAN 6 1986 FIRST PUBLISHED New Australian children's book released Mfll Y fIBOUT PEOPLE The Australian x 1880 DIOCESE OF MELBOURNE Diocese of Melbourne to Assistant Chaplain CitURCII Anderson, Neville From assistant curate at St and Director of Outdoor Education at St 105 years serving the Gospel and Michael's Grammar School from 1st February, Andrew's Brighton to assistant curate St its ministry Matthew's Cheltenham from 1st November, 1986. 1985. Wood, David G. Fron incumbency St John's Beaumont, Gerald From Priest-in-Charge All Sort en to to incumbency St. John's Croydon. Saints' Kooyong to incumbent of Holy Trinity East Melbourne. Induction to be in February, Resignations. RECORD 1986. 50 CENTS Costigan, Gerard F. From Priest-in-Charge St. 1840 DECEMBER 16, 1985 Registered by Australia Post Publication No. NAR1 678 Telephone 264 8349 PRICE Benfield, Desmond From incumbent of Holy Alban's North Melbourne to become Rector of Advent Malvern to incumbent St. Eanswyth's Alice Springs in the Diocese of the Northern Altona. Territory, from January, 1986. Cohen, Vernon From incumbent of St Bede's Gaden, John R. From Director of Trinity Elwood to Minor Canon and Associate Priest Theological School, Chaplain to the How's that .. for a book launching of St. Paul's Cathedral, Melbourne, from 15th Canterbury Fellowship and Archbishop's October. Consultant Theologian — to become Warden Archbishop Farrer, R. David of St Barnabas' College, Adelaide, from Elected as Canon of St. Paul's February, 1986. Cathedral, Melbourne, October, 1985. Goldsworthy, John I.. Induction to St Paul's Retirements: Boronia. -

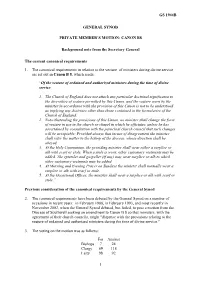

Gs 1944B General Synod Private Member's Motion

GS 1944B GENERAL SYNOD PRIVATE MEMBER’S MOTION: CANON B8 Background note from the Secretary General The current canonical requirements 1. The canonical requirements in relation to the vesture of ministers during divine service are set out in Canon B 8, which reads: “Of the vesture of ordained and authorized ministers during the time of divine service 1. The Church of England does not attach any particular doctrinal significance to the diversities of vesture permitted by this Canon, and the vesture worn by the minister in accordance with the provision of this Canon is not to be understood as implying any doctrines other than those contained in the formularies of the Church of England. 2. Notwithstanding the provisions of this Canon, no minister shall change the form of vesture in use in the church or chapel in which he officiates, unless he has ascertained by consultation with the parochial church council that such changes will be acceptable: Provided always that incase of disagreement the minister shall refer the matter to the bishop of the diocese, whose direction shall be obeyed. 3. At the Holy Communion, the presiding minister shall wear either a surplice or alb with scarf or stole. When a stole is worn, other customary vestments may be added. The epistoler and gospeller (if any) may wear surplice or alb to which other customary vestments may be added. 4. At Morning and Evening Prayer on Sundays the minister shall normally wear a surplice or alb with scarf or stole. 5. At the Occasional Offices, the minister shall wear a surplice or alb with scarf or stole.” Previous consideration of the canonical requirements by the General Synod 2. -

23Rd July 1984

s "Marriage like gardening" says Flo Bjelke-Petersen Australian Eddy Waxer, incredulity cont The Australian FIRST PUBLISHED pro-tennis and IN MO christian CHURCH Birth narratives less important Eddy Waxer of 'SPORTS & RECREATION Rev. Dr. John Gaden, Canon Theologian THROUGH THE 20th CENTURY CHURCH' of the Diocese of Melbourne and from Miami Florida, USA, visited Sydney in Archbishop's Consultant Theologian, was June and met with a number of the unwilling to comment directly on the Australian Christian Sports Fellowship. reported poll conducted by London Waxer 38, has been set aside by his home RECORD Weekend Television. This, he said, was partly due to the distance between us and church, the Key Biscayne Presbyterian 1806 JULY 23, 1984 Registered by Australia Post Publication No NAR1678 Telephone 264 8349 PRICE 50 CENTS Britain, and also because he had knowledge Church, to minister to sports people of the English bishops' beliefs from their throughout the world. writings, and from personal contacts. "It is He is a man who has been given a L to Mrs. Diane Stein (HMS Women's Auxiliary Sec-t, d1n. it,. actually hard to believe that they said what 'vision' of God to utilise sports as a means 13(elke-Petersen, Mrs. Robinson. they were reported to say". to bring people into a living relationship "If I was asked, 'Is Jesus God?' ", Dr. with Jesus Christ. "Marriage is like gardening — it takes time, Senator Bjelke-Petersen told her audience Increase Gospel, by popular demand! Gaden continued, "I would not be able to A former international tennis circuit care, nourishment and love," Senator Flo that 1984 in Queensland is 'The Year of the give a blank, unqualified 'yes. -

Ttbe ©Rnaments 1Rubric. the BISHOP of MANCHESTER and the E.C.U

THE ORNAMENTS RUBRIC ttbe ©rnaments 1Rubric. THE BISHOP OF MANCHESTER AND THE E.C.U. BY THE REV. c. SYDNEY CARTER, M.A., Chaplain of St. Mary Magdalen, Bath. E suppose that the Bishop of Manchester is to be com W plimented on having been considered a sufficiently com petent authority to engage the attention of the legal committee of the English Church Union. Their Council have issued a "Criticism. and Reply" 1 to his lordship's recent "Open Letter" to the Primate, in which he seriously challenged the exparte con clusions contained in the " Report of the Five Bishops " of Canterbury Convocation on the Ornaments Rubric. This curiously worded pamphlet certainly reflects far more credit on the ingenuity and casuistry than on the ability and accurate knowledge of the legal committee of the E.C. U. It abounds in unwarrantable assumptions, glaring inaccuracies, flagrant misrepresentations, and careful suppression of facts ; and the Bishop of Manchester is certainly to be congratulated if his weighty contention encounters no more serious or damaging opposition than is afforded in these twenty-four pages. One or two examples will sufficiently illustrate the style of argument employed throughout. The natural conclusion stated in the '' Report," that the omission in prayers and rubrics of a cere mony or ornament previously used was '' the general method employed" by the compilers of the Prayer-Books for its aboli tion or prohibition, is contemptuously dismissed in this pamphlet as an " untenable theory." Thus, not only are we told that the Ornaments Rubric was definitely framed as "the controlling guide" of what ornaments were to be retained and used and as "a guide for the interpretation of other rubrics," but that it is also "a directory to supply omissions as to ceremonies which 1 " The Ornaments Rubric and the Bishop of Manchester's Letter : A Criticism and .a Reply." Published by direction of the Council of the English Church Union. -

Book of Common Prayer

The History of the Book of Common Prayer BY THE REV. J. H. MAUDE, M.A. FORMERLY FELLOW AND DEAN OF HERTFORD COLLEGE, OXFORD TENTH IMPRESSION SIXTH EDITION RIVINGTONS 34 KING STREET, COVENT GARDEN LONDON 1938 Printed in Great Britain by T. AND A.. CoNSTABLE L'PD. at the University Press, Edinburgh CONTENTS ORAl'. I. The Book of Common Prayer, 1 11. The Liturgy, 16 In•• The Daily Office, 62 rv. The Occasional Offices~ 81 v. The Ordinal, 111 VI. The Scottish Liturgy, • 121 ADDITIONAL NoTES Note A. Extracts from Pliny and Justin Ma.rtyr•• 1.26 B. The Sarum Canon of the Mass, m C. The Doctrine of the Eucharist, 129 D. Books recommended for further Study, • 131 INDBX, 133 THE BOOK OF COMMON PRAYER CHAPTER I THE BOOK OF COl\IMON PRAYER The Book of Common Prayer.-To English churchmen of the present day it appears a most natural arrangement that all the public services of the Church should be included in a single book. The addition of a Bible supplies them with everything that forms part of the authorised worship, and the only unauthorised supple ment in general use, a hymn book, is often bound up with the other two within the compass of a tiny volume. It was, however, only the invention of printing that rendered such compression possible, and this is the only branch of the Church that has effected it. In the Churches of the West during the Middle Ages, a great number of separate books were in use; but before the first English Prayer Book was put out in 1549, a process of combination had reduced the most necessary books to five, viz. -

Newsletter O

newsletter o )( &uly '%,- ISSN 1836-511 WEBSITE: www.anglicantogether.org ST PAUL’S BURWOOD WON THIS YEAR’S NATIONAL TRUST HERITAGE AWARD FOR THE 2017 ANNUAL DINNER CATEGORY “CONSERVATION INTERIORS”. FRIDAY 25TH AUGUST - 7 PM The Awards Ceremony, on 28th February 2017 Guest Speaker – was attended by three hundred and thirty people who were there to witness the presentation of the Professor Martyn Percy, Awards in very many dfferent categories. Dean of Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford Mrs Pam Brock and Dr Jane Wood, Church Wardens received the Award Certificate. In accepting the Award, Pam Brock thanked the architects, those who gained the grant application, and all “WHY BE AN ANGLICAN?” parishioners who, not only dealt with VENUE: Cello’s Restaurant, the inconveniences of not having a church building, Castlereagh Boutique Hotel but also generously donated monies to bring the 169 Castlereagh Street, Sydney Restoration Project to fruition. The judges unanimously described the Project COST: $70 pp ($65 conc) as one of "sheer joy." Pay on line: www.anglicanstogther.org OR Payment with Response Form - see back page by 14 August 2017 to Anglicans Together, Level 1, St James Hall, 169-171 Phillip St, Sydney Telephone 01 8227 1300 ANGLICANS TOGETHER ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING & DISCUSSION SUNDAY, 24th SEPTEMBER 2017 This prestigious Award recognizes the value of the 2.00 PM work done to restore the beautiful St Paul’s church St James’ Hall, to Blacket's original vision. It stands as a beacon of 169-171 Phillip Street, Sydney heritage in the inner west, and creates an aesthetic that enhances the worship of God. -

Oak Hill College Ask the Lord of the Harvest

Commentary SPECIAL EDITION 2017 In thanksgiving for the life and ministry of The goal of Mike’s work was a new MIKE OVEY reformation, and 1958-2017 his significance is as a reformer, says Don Carson With tributes from Page 4 colleagues, Oak Hill alumni and fellow church leaders Mark Thompson pays tribute to Mike’s educational vision, while John Stevens is grateful for the way he brought Independent and Anglican students together Pages 16 and 19 Oak Hill College Ask the Lord of the harvest The testimonies in these pages give us an opportunity to thank God for the life of his servant Mike Ovey, and to pray for the partnership of Oak he would want anyone to do would be to stop praying for Hill and the churches to proclaim the the Lord of the harvest to send fresh workers into the field. gospel in our time, says Dan Strange, And in fact, this is exactly what God has been doing, and Acting Principal of Oak Hill continues to do, through the ministry of Oak Hill. God has been sending gospel ministers, youth leaders, church planters, women’s workers, and cross-cultural In the middle of his ministry, Jesus was besieged by missionaries, who come to the college community to learn large crowds who came to him for healing, teaching and how to become servants of the word of God and of the leadership. Seeing the people, who were like sheep without a people of God. Now is the time for the church and the shepherd, Jesus turned to his disciples and said, ‘The harvest college to step up their partnership in order to flood our is plentiful but the workers are few. -

The Oxford Movement in the Southern Presbyterian Church

THE UNION SEMINARY MAGAZINE , NO. 3–JAN.-FEB., 1897. \ i t I.—LITERARY. THE OXFORD MOVEMENT IN THE SOUTHERN PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH. The Oxford Movement in the Church of England began about 1833. It was a reaction against liberalism in politics, latitudinarianism in theology, and the government of the Church by the State. It was, at the same time, a return to Mediaeval theology and worship. The doctrines of Apostoli cal Succession, and the Real Presence—a doctrine not to be distinguished from the Roman Catholic doctrine of transub stantiation—were revived. And along with this return to Mediaeval theology, Mediaeval architecture was restored; temples for a stately service were prepared; not teaching halls. Communion tables were replaced by altar's. And the whole paraphernalia of worship was changed ; so that, except for the English tongue and the mustaches of the priests, the visitor could hardly have told whether the worship were that of the English Church or that of her who sitteth on “the seven hills.” It must be admitted that there was some good in the move ment. The Erastian theory as to the proper relation of Church and State is wrong. The kingdom of God should not be sub ordinate to any “world-power.” No state should control the Church. And certainly such latitudinarianism in doctrine as that of Bishop Coleuso and others called for a protest. But the return to Mediaeval theology and Mediaeval worship was all wrong. We have no good ground for doubting the sincerity of many of the apostles of the movement. Unfortunately, more than 146 THE UNION SEMINARY MAGAZINE. -

GS Misc 1133 HOUSE of BISHOPS CONSULTATION on VESTURE 1

GS Misc 1133 HOUSE OF BISHOPS CONSULTATION ON VESTURE CANON B 8 (VESTURE) CONSULTATION PAPER FOR MEMBERS OF GENERAL SYNOD FROM THE HOUSE OF BISHOPS Summary 1. At its meeting in December 2015, the House of Bishops agreed to consult Synod members to seek their views on whether the House should promote the introduction of draft legislation to amend Canon B 8 (‘Of the vesture of ordained and authorized ministers during the time of divine service’). The House will consider the responses received at their meeting on 23 – 24 May and will decide then whether and, if so, when legislation on the subject should be introduced. 2. Synod members are asked to send their responses to the questions set out in the Conclusions to the Clerk to the Synod by 5pm on Friday 15 April. Background 3. At the July 2014 group of sessions, the General Synod resolved, on a Private Member’s Motion (PMM) from the Rev’d Canon Christopher Hobbs (London), as follows: ‘That this Synod call on the Business Committee to introduce draft legislation to amend the law relating to the vesture of ministers so that, without altering the principles set out in paragraphs 1 and 2 of Canon B.8., the wearing of forms of vesture referred to in paragraphs 3,4 and 5 of that Canon becomes optional rather than mandatory.’ 4. Canon B 8 currently reads as follows: 1. The Church of England does not attach any particular doctrinal significance to the diversities of vesture permitted by this Canon, and the vesture worn by the minister in accordance with the provision of this Canon is not to be understood as implying any doctrines other than those now contained in the formularies of the Church of England.