Book of Common Prayer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holy Communion

The Book of Common Prayer, as printed by John Baskerville This document is intended to exactly reproduce The 1662 Book of Common Prayer as printed by John Baskerville in 1762. This particular printing appears in David Griffiths' “Bibliography of the Book of Common Prayer” as 1762/4; and is #19 in Phillip Gaskell's bibliography of Baskerville's works. The font used is John Baskerville, from Storm Foundries, which is very close to the original and includes all the characters used in this book. The original pages are slightly larger than half of an 8½ x 11" piece of paper, so all dimensions of the original were reduced by about 8% to fit (e. g., the typeface is 13 point, rather than the original 14 point). Line and page breaks may be slightly different than in the original. You may redistribute this document electronically provided no fee is charged and this header remains part of the document. While every attempt was made to ensure accuracy, certain errors may exist in the text. Please contact us if any errors are found. This document was created as a service to the community by Satucket Software: Web Design & computer consulting for small business, churches, & non-profits Contact: Charles Wohlers P. O. Box 227 East Bridgewater, Mass. 02333 USA [email protected] http://satucket.com The O R D E R for the The COMMUNION. U R Father, which art in heaven, Hal- Administration of the LORD’s SUPPER, O lowed be thy Name; Thy kingdom come; OR Thy will be done in earth, as it is in heaven: Give us this day our daily bread; And forgive HOLY COMMUNION. -

The Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church Church Publishing Incorporated, New York Certificate I certify that this edition of The Book of Common Prayer has been compared with a certified copy of the Standard Book, as the Canon directs, and that it conforms thereto. Gregory Michael Howe Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer January, 2007 Table of Contents The Ratification of the Book of Common Prayer 8 The Preface 9 Concerning the Service of the Church 13 The Calendar of the Church Year 15 The Daily Office Daily Morning Prayer: Rite One 37 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite One 61 Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two 75 Noonday Prayer 103 Order of Worship for the Evening 108 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite Two 115 Compline 127 Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families 137 Table of Suggested Canticles 144 The Great Litany 148 The Collects: Traditional Seasons of the Year 159 Holy Days 185 Common of Saints 195 Various Occasions 199 The Collects: Contemporary Seasons of the Year 211 Holy Days 237 Common of Saints 246 Various Occasions 251 Proper Liturgies for Special Days Ash Wednesday 264 Palm Sunday 270 Maundy Thursday 274 Good Friday 276 Holy Saturday 283 The Great Vigil of Easter 285 Holy Baptism 299 The Holy Eucharist An Exhortation 316 A Penitential Order: Rite One 319 The Holy Eucharist: Rite One 323 A Penitential Order: Rite Two 351 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two 355 Prayers of the People -

Holy Communion, Anglican Standard Text, 1662 Order FINAL

Concerning the Service Holy Communion is normally the principal service of Christian worship on the Lord’s Day, and on other appointed Feasts and Holy Days. Two forms of the liturgy, commonly called the Lord’s Supper or the Holy Eucharist, are provided. The Anglican Standard Text is essentially that of the Holy Communion service of the Book of Common Prayer of 1662 and successor books through 1928, 1929 and 1962. The Anglican Standard Text is presented in contemporary English and in the order for Holy Communion that is common, since the late twentieth century, among ecumenical and Anglican partners worldwide. The Anglican Standard Text may be conformed to its original content and ordering, as in the 1662 or subsequent books; the Additional Directions give clear guidance on how this is to be accomplished. Similarly, there are directions given as to how the Anglican Standard Text may be abbreviated where appropriate for local mission and ministry. The Renewed Ancient Text is drawn from liturgies of the Early Church, reflects the influence of twentieth century ecumenical consensus, and includes elements of historic Anglican piety. A comprehensive collection of Additional Directions concerning Holy Communion is found after the Renewed Ancient Text: The order of Holy Communion according to the Book of Common Prayer 1662 The Anglican Standard Text may be re-arranged to reflect the 1662 ordering as follows: The Lord’s Prayer The Collect for Purity The Decalogue The Collect of the Day The Lessons The Nicene Creed The Sermon The Offertory The Prayers of the People The Exhortation The Confession and Absolution of Sin The Comfortable Words The Sursum Corda The Sanctus The Prayer of Humble Access The Prayer of Consecration and the Ministration of Communion (ordered according to the footnote) The Lord’s Prayer The Post Communion Prayer The Gloria in Excelsis The Blessing The precise wording of the ACNA text and rubrics are retained as authorized except in those places where the text would not make grammatical sense. -

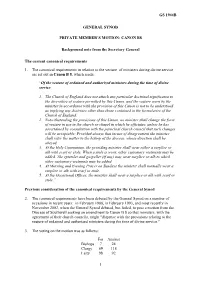

Gs 1944B General Synod Private Member's Motion

GS 1944B GENERAL SYNOD PRIVATE MEMBER’S MOTION: CANON B8 Background note from the Secretary General The current canonical requirements 1. The canonical requirements in relation to the vesture of ministers during divine service are set out in Canon B 8, which reads: “Of the vesture of ordained and authorized ministers during the time of divine service 1. The Church of England does not attach any particular doctrinal significance to the diversities of vesture permitted by this Canon, and the vesture worn by the minister in accordance with the provision of this Canon is not to be understood as implying any doctrines other than those contained in the formularies of the Church of England. 2. Notwithstanding the provisions of this Canon, no minister shall change the form of vesture in use in the church or chapel in which he officiates, unless he has ascertained by consultation with the parochial church council that such changes will be acceptable: Provided always that incase of disagreement the minister shall refer the matter to the bishop of the diocese, whose direction shall be obeyed. 3. At the Holy Communion, the presiding minister shall wear either a surplice or alb with scarf or stole. When a stole is worn, other customary vestments may be added. The epistoler and gospeller (if any) may wear surplice or alb to which other customary vestments may be added. 4. At Morning and Evening Prayer on Sundays the minister shall normally wear a surplice or alb with scarf or stole. 5. At the Occasional Offices, the minister shall wear a surplice or alb with scarf or stole.” Previous consideration of the canonical requirements by the General Synod 2. -

The Monastic Rules of Visigothic Iberia: a Study of Their Text and Language

THE MONASTIC RULES OF VISIGOTHIC IBERIA: A STUDY OF THEIR TEXT AND LANGUAGE By NEIL ALLIES A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham July 2009 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis is concerned with the monastic rules that were written in seventh century Iberia and the relationship that existed between them and their intended, contemporary, audience. It aims to investigate this relationship from three distinct, yet related, perspectives: physical, literary and philological. After establishing the historical and historiographical background of the texts, the thesis investigates firstly the presence of a monastic rule as a physical text and its role in a monastery and its relationship with issues of early medieval literacy. It then turns to look at the use of literary techniques and structures in the texts and their relationship with literary culture more generally at the time. Finally, the thesis turns to issues of the language that the monastic rules were written in and the relationship between the spoken and written registers not only of their authors, but also of their audiences. -

Building on a Rickety Foundation: “An Evangelical Agenda”

BUILDING ON A RICKETY FOUNDATION: “AN EVANGELICAL AGENDA” James McPherson During one of the meal adjournments from Synod 2001, the Revd Phillip Jensen addressed the Anglican Church League. It was a “missionary” address, titled “An Evangelical Agenda”.1 He promoted “church-planting” and outlined a putative justification for his proposed strategy. His address was notable for its sweeping generalisations and innuendo, eg about “revisionism” and the alleged evils of Tractarianism. Putting to one side all matters of rhetorical technique, the logic of Mr Jensen’s address was that • “the parish system” was working well; • until the Tractarians damaged the parish system irreparably; • so the remedy is to bypass existing parishes damaged by Tractarian and other revisions, and restore authentic Anglicanism. He went further, concluding his address by urging ACL members to campaign so that the churches planted by those who have been forced outside the denomination (ie, by collateral damage to its theology and institutional structures) should be embraced as part of the Anglican family. It is clear from his address that he is promoting competitive rather than collaborative church- planting. That is, this church-planting is not undertaken with the full knowledge and willing cooperation of an existing Anglican parish, but because the existing parish is judged to be defective and thus for the cause of the gospel should be challenged, exposed, and perhaps even extinguished. I intend to show first that Mr Jensen’s proposal bristles with practical difficulties; and second, that it is based on a theologically prejudiced reading of history. Such a view of the past does not commend those who hold it as reliable guides for the future. -

The Development of the Book of Common Prayer

Summary Document by Rev. David Peer Diocese of Fredericton The Development of the Book of Common Prayer The purpose of this document is to trace the development of the Canadian Book of Common Prayer from its origins in England to today. A great resource for anyone interested in the Canadian Book of Common Prayer is the Prayer Book Society website http://prayerbook.ca/the-prayer-book, where you can find the 1962 Canadian Prayer Book online. Another great resource online is a site hosted by the Society of Archbishop Justus incorporated in 1997 as a non-profit corporation in the State of New York http://justus.anglican.org/resources/bcp/. It has a number of Anglican historical publications concerning the Prayer Book. What is the Book of Common Prayer, how does it function for the Church of England and other Anglican Churches? The 1962 Canadian revision of The Book of Common Prayer is the official prayer book of the Anglican Church of Canada. It is the second Canadian edition in a line of Books of Common Prayer, originating in the sixteenth century English Reformation. The Book of Common Prayer includes official doctrinal positions, such as the Creeds, the Solemn Declaration of 1893, and the 39 Articles of Religion. It is also the source for the forms for administering: Holy Communion (along with the Collects, Epistles, and Gospels used at Communion and other services), Baptism, Matrimony, and Burials. It also contains the ordination rites of the Anglican Church. The Book of Common Prayer also includes the offices, services of morning and evening prayer, along with tables for reading through the Bible yearly and Psalms monthly as a part of the offices. -

PRI Chalice Lessons-All Units

EPISCOPAL CHILDREN’S CURRICULUM PRIMARY CHALICE Chalice Year Primary Copyright © 2009 Virginia Theological Seminary i Locke E. Bowman, Jr., Editor-in-Chief Amelia J. Gearey Dyer, Ph.D., Associate Editor The Rev. George G. Kroupa III, Associate Editor Judith W. Seaver, Ph.D., Managing Editor (1990-1996) Dorothy S. Linthicum, Managing Editor (current) Consultants for the Chalice Year, Primary Charlie Davey, Norfolk, VA Barbara M. Flint, Ruxton, MD Martha M. Jones, Chesapeake, VA Burleigh T. Seaver, Washington, DC Christine Nielsen, Washington, DC Chalice Year Primary Copyright © 2009 Virginia Theological Seminary ii Primary Chalice Contents BACKGROUND FOR TEACHERS The Teaching Ministry in Episcopal Churches..................................................................... 1 Understanding Primary-Age Learners .................................................................................. 8 Planning Strategies.............................................................................................................. 15 Session Categories: Activities and Resources ................................................................... 21 UNIT I. JUDGES/KINGS Letter to Parents................................................................................................................... I-1 Session 1: Joshua................................................................................................................. I-3 Session 2: Deborah............................................................................................................. -

The Catholic University of America A

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA A Manual of Prayers for the Use of the Catholic Laity: A Neglected Catechetical Text of the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By John H. Osman Washington, D.C. 2015 A Manual of Prayers for the Use of the Catholic Laity: A Neglected Catechetical Text of the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore John H. Osman, Ph.D. Director: Joseph M. White, Ph.D. At the 1884 Third Plenary Council of Baltimore, the US Catholic bishops commissioned a national prayer book titled the Manual of Prayers for the Use of the Catholic Laity and the widely-known Baltimore Catechism. This study examines the Manual’s genesis, contents, and publication history to understand its contribution to the Church’s teaching efforts. To account for the Manual’s contents, the study describes prayer book genres developed in the British Isles that shaped similar publications for use by American Catholics. The study considers the critiques of bishops and others concerning US-published prayer books, and episcopal decrees to address their weak theological content. To improve understanding of the Church’s liturgy, the bishops commissioned a prayer book for the laity containing selections from Roman liturgical books. The study quantifies the text’s sources from liturgical and devotional books. The book’s compiler, Rev. Clarence Woodman, C.S.P., adopted the English manual prayer book genre while most of the book’s content derived from the Roman Missal, Breviary, and Ritual, albeit augmented with highly regarded English and US prayers and instructions. -

Ttbe ©Rnaments 1Rubric. the BISHOP of MANCHESTER and the E.C.U

THE ORNAMENTS RUBRIC ttbe ©rnaments 1Rubric. THE BISHOP OF MANCHESTER AND THE E.C.U. BY THE REV. c. SYDNEY CARTER, M.A., Chaplain of St. Mary Magdalen, Bath. E suppose that the Bishop of Manchester is to be com W plimented on having been considered a sufficiently com petent authority to engage the attention of the legal committee of the English Church Union. Their Council have issued a "Criticism. and Reply" 1 to his lordship's recent "Open Letter" to the Primate, in which he seriously challenged the exparte con clusions contained in the " Report of the Five Bishops " of Canterbury Convocation on the Ornaments Rubric. This curiously worded pamphlet certainly reflects far more credit on the ingenuity and casuistry than on the ability and accurate knowledge of the legal committee of the E.C. U. It abounds in unwarrantable assumptions, glaring inaccuracies, flagrant misrepresentations, and careful suppression of facts ; and the Bishop of Manchester is certainly to be congratulated if his weighty contention encounters no more serious or damaging opposition than is afforded in these twenty-four pages. One or two examples will sufficiently illustrate the style of argument employed throughout. The natural conclusion stated in the '' Report," that the omission in prayers and rubrics of a cere mony or ornament previously used was '' the general method employed" by the compilers of the Prayer-Books for its aboli tion or prohibition, is contemptuously dismissed in this pamphlet as an " untenable theory." Thus, not only are we told that the Ornaments Rubric was definitely framed as "the controlling guide" of what ornaments were to be retained and used and as "a guide for the interpretation of other rubrics," but that it is also "a directory to supply omissions as to ceremonies which 1 " The Ornaments Rubric and the Bishop of Manchester's Letter : A Criticism and .a Reply." Published by direction of the Council of the English Church Union. -

Book of Common Prayer Which

November/December 1998 Volume 17, Numbers THE BI-MONTHLY MAGAZINE OF THE SOCIETY FOR THE PRESERVATION OF THE BOOK OF COMMON PRAYER WHICH U TOJlllllllKWIIMffllfm B.C.P.. ORDINAL & 39 ARTICLES CONTENTS 3. Reflections from the Editor's Desk; Am I inconsistent on Formularies? 4. Common Prayer and the Book of Common Prayer: How are they related? 5. FORMULARIES 1. Forms, Formulas and Formularies of the Anglican Way. 7. FORMULARIES 2. The present agony of the Anglican Way. 8. FORMULARIES 3. God's creation: Existence with Forms. 9. FORMULARIES 4. Jesus Christ, form of God and form of Man. 10. The Common Prayer and the Renewal Movement. 11. The first American Book of Common Prayer (1789). 13. The '79 Rehgion of the American Episcopal Church. 15. Archbishop Cranmer, Midwife or Father. 16. An Intemet Mission for an Anglican Future. What is the Prayer Book Society? First of all, what it is not: 1. It is not a historical society — though it does take history seriously. 2. It is not merely a preservation society — though it does seek to preserve what is good. 3. It is not merely a traditionalist society — though it does receive holy tradition gratefully. 4. It is not a reactionary society, existing only by opposing modem trends. 5. It is not a synod or council, organized as a church within the Church. In the second place, what it is: 1. It is composed of faithful Episcopalians who seek to keep alive in the Church the classic Common Prayer Tradition of the Anglican Way, which began within the Church of England in 1549. -

Book of Common Prayer

the book of common prayer and administration of the s a c r a m e n t s with other rites and ceremonies of the church According to the use of the anglican church in north america Together with the new coverdale psalter anno domini 2019 anglican liturgy press the book of common prayer (2019) Copyright © 2019 by the Anglican Church in North America The New Coverdale Psalter Copyright © 2019 by the Anglican Church in North America Published by Anglican Liturgy Press an imprint of Anglican House Media Ministry, Inc. 16332 Wildfire Circle Huntington Beach, CA 92649 Publication of the Book of Common Prayer (2019), including the New Coverdale Psalter, is authorized by the College of Bishops of the Anglican Church in North America. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except as provided for by USA copyright law, and except as indicated below for the incorporation of selections (liturgies) in bulletins or other materials for use in church worship services. First printing, June 2019 Second (corrected) printing, November 2019 Third printing, November 2019 Quotations of Scripture in the Book of Common Prayer (2019) normally follow the ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®) except for the Psalms, Canticles, and citations marked with the symbol (T), which indicates traditional prayer book language. The ESV Bible copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. ESV Text Edition: 2016.