Cramerdearmersot17.Pdf (533.6Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Choral Evensong the 18Th Sunday After Trinity

ST EDMUND HALL Choral Evensong The 18th Sunday after Trinity Speaker: The Revd Anthony Buckley Being oneself, changing the world 11 October 2020 6.30 pm What is Evensong? Evensong is one of the Church of England’s ancient services. It provides an open and generous space for quiet and reflection, for song and speech and prayer, as it draws from biblical readings, canticles, and the Church’s long tradition of hymns. All are welcome. Many have said, “Prayer is the key to the day and the lock to the night.” In the Anglican tradition, daily prayer is set at morning and evening for precisely this purpose: to give the opportunity to greet each new day as a divine gift and to prepare our hearts and minds for rest each night. It is founded in a sense of gratitude and wonder, and centred on the faith of Jesus Christ. We invite everyone to join in, as they are able, by listening attentively to the choir, readers, and ministers, and by saying together with us those prayers that are marked in bold: the Lord’s Prayer, the Grace, and the Amens. This year, we are meeting in many locations, not just in the Chapel. Space is primarily limited to the choir, readers, and speaker, but contact the chaplain to enquire about seating. Those who cannot join us in person may do so by Zoom at: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/87112377996?pwd=bm9zMWZreEl4M1RiK2to OXNvNW9aZz09 Please join us for drinks after the service. Speaker Our speaker this evening is the Revd Anthony Buckley, Vicar of St Michael at the North Gate. -

Choral Evensong with Carols

THE CATHEDRAL AND METROPOLITICAL CHURCH OF CHRIST, CANTERBURY Choral Evensong with Carols Christmas Eve Thursday 24th December 2020 5.30pm Welcome to Canterbury Cathedral for this Service For your safety Please keep social distance at all times Please stay in your seat as much as possible Please use hand sanitiser on the way in and out Please avoid touching your face and touching surfaces Cover Image: The Nativity (Christopher Whall) South West Transept, Canterbury Cathedral Transept As part of our commitment to the care of the environment in our world, this Order of Service is printed on unbleached 100% recycled paper Please ensure that mobile phones are switched off. No form of visual or sound recording, or any form of photography, is permitted during Services. Thank you for your co-operation. An induction loop system for the hard of hearing is installed in the Cathedral. Hearing aid users should adjust their aid to T. Large print orders of service are available from the stewards and virgers. Please ask. Some material included in this service is copyright: © The Archbishops' Council 2000 © The Crown/Cambridge University Press: The Book of Common Prayer (1662) Hymns and songs reproduced under CCLI number: 1031280 Produced by the Music & Liturgy Department: [email protected] 01227 865281 www.canterbury-cathedral.org ORDER OF SERVICE All stand as the choir and clergy enter the Nave Welcome The Dean Please remain standing Introit O little one sweet, O little one sweet, O little one mild, O little one mild, thy Father’s purpose thou hast fulfilled; with joy thou hast the whole world filled; thou cam’st from heav’n to mortal ken thou camest here from heaven’s domain equal to be with us poor men, to bring men comfort in their pain, O little one sweet, O little one sweet, O little one mild. -

CHORAL EVENSONG World Without End

Then shall the earth bring forth her increase: and God, even our own God, shall give us his blessing. God shall bless us: and all the ends of the world shall fear him. Glory be to the Father, and to the Son: and to the Holy Ghost; As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be: CHORAL EVENSONG world without end. Amen. Tuesday 29 May 2018 The FIRST LESSON is read Exodus 2: 11–end (NRSV p. 47) Welcome to this service of Choral Evensong All stand for the MAGNIFICAT sung by The Choir of Trinity College Cambridge Tonus peregrinus Plainsong Please ensure that all electronic devices, My soul doth magnify the Lord, and my spirit hath rejoiced including cameras, are switched off in God my Saviour. For he hath regarded the lowliness of his handmaiden. For behold, from henceforth all generations VOLUNTARY shall call me blessed. For he that is mighty hath magnified me: and holy is his Name. And his mercy is on them that Flûtes, Op. 91/4 Langlais fear him throughout all generations. He hath shewed strength with his arm; he hath scattered the proud in the INTROIT sung from the Ante-Chapel imagination of their hearts. He hath put down the mighty Benedicta sit from their seat, and hath exalted the humble and meek. Blessed be the Holy Trinity and the undivided Unity: He hath filled the hungry with good things; and the rich we will praise and glorify him, because he hath showed he hath sent empty away. He remembering his mercy hath his mercy upon us. -

This Chapter Will Demonstrate How Anglo-Catholicism Sought to Deploy

Building community: Anglo-Catholicism and social action Jeremy Morris Some years ago the Guardian reporter Stuart Jeffries spent a day with a Salvation Army couple on the Meadows estate in Nottingham. When he asked them why they had gone there, he got what to him was obviously a baffling reply: “It's called incarnational living. It's from John chapter 1. You know that bit about 'Jesus came among us.' It's all about living in the community rather than descending on it to preach.”1 It is telling that the phrase ‘incarnational living’ had to be explained, but there is all the same something a little disconcerting in hearing from the mouth of a Salvation Army officer an argument that you would normally expect to hear from the Catholic wing of Anglicanism. William Booth would surely have been a little disconcerted by that rider ‘rather than descending on it to preach’, because the early history and missiology of the Salvation Army, in its marching into working class areas and its street preaching, was precisely about cultural invasion, expressed in language of challenge, purification, conversion, and ‘saving souls’, and not characteristically in the language of incarnationalism. Yet it goes to show that the Army has not been immune to the broader history of Christian theology in this country, and that it too has been influenced by that current of ideas which first emerged clearly in the middle of the nineteenth century, and which has come to be called the Anglican tradition of social witness. My aim in this essay is to say something of the origins of this movement, and of its continuing relevance today, by offering a historical re-description of its origins, 1 attending particularly to some of its earliest and most influential advocates, including the theologians F.D. -

The Fabians Could Only Have Happened in Britain....In a Thoroughly Admirable Study the Mackenzies Have Captured the Vitality of the Early Years

THE famous circle of enthusiasts, reformers, brilliant eccentrics-Sha\y the Webbs, Wells-whose ideas and unconventional attitudes fashioned our modern world by Norman C&Jeanne MacKenzie AUTHORS OF H.G. Wells: A Biography PRAISE FOR Not quite a political party, not quite a pressure group, not quite a debating society, the Fabians could only have happened in Britain....In a thoroughly admirable study the MacKenzies have captured the vitality of the early years. Since much of this is anecdotal, it is immensely fun to read. Most im¬ portant, they have pinpointed (with¬ out belaboring) all the internal para¬ doxes of F abianism. —The Kirkus Reviews H. G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw, Sidney and Beatrice Webb, Bertrand Russell, part of the outstandingly talented and paradoxical group that led the way to socialist Britain, are brought into brilliant human focus in this marvelously detailed and anecdote-filled por¬ trait of the original members of the Fabian Society—with a fresh assessment of their contributions to social thought. “The first Fabians,” said Shaw, were “missionaries among the savages,” who laid the ground¬ work for the Labour Party, and whose mis¬ sionary zeal and passionate enthusiasms carried them from obscurity to fame. This voluble and volatile band of middle-class in¬ tellectuals grew up in a period of liberating ideas and changing morals, influenced by (continued on back flap) c A / c~ 335*1 MacKenzie* Norman Ian* Ml99f The Fabians / Norman and Jeanne MacKenzie* - New York : Simon and Schuster, cl977* — 446 p** [8] leaves of plates : ill* - ; 24 cm* Includes bibliographical references and index* ISBN 0—671—22347—X : $11.95 1* Fabian Society, London* I* Title. -

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms Liturgical Objects Used in Church The chalice: The The paten: The vessel which golden “plate” that holds the wine holds the bread that that becomes the becomes the Sacred Precious Blood of Body of Christ. Christ. The ciborium: A The pyx: golden vessel A small, closing with a lid that is golden vessel that is used for the used to bring the distribution and Blessed Sacrament to reservation of those who cannot Hosts. come to the church. The purificator is The cruets hold the a small wine and the water rectangular cloth that are used at used for wiping Mass. the chalice. The lavabo towel, The lavabo and which the priest pitcher: used for dries his hands after washing the washing them during priest's hands. the Mass. The corporal is a square cloth placed The altar cloth: A on the altar beneath rectangular white the chalice and cloth that covers paten. It is folded so the altar for the as to catch any celebration of particles of the Host Mass. that may accidentally fall The altar A new Paschal candles: Mass candle is prepared must be and blessed every celebrated with year at the Easter natural candles Vigil. This light stands (more than 51% near the altar during bees wax), which the Easter Season signify the and near the presence of baptismal font Christ, our light. during the rest of the year. It may also stand near the casket during the funeral rites. The sanctuary lamp: Bells, rung during A candle, often red, the calling down that burns near the of the Holy Spirit tabernacle when the to consecrate the Blessed Sacrament is bread and wine present there. -

An Argument for the Wider Adoption and Use of Traditional Academic Attire Within Roman Catholic Church Services

Transactions of the Burgon Society Volume 17 Article 7 10-21-2018 An Argument for the Wider Adoption and Use of Traditional Academic Attire within Roman Catholic Church Services Seamus Addison Hargrave [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/burgonsociety Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Higher Education Commons, History of Christianity Commons, and the Religious Education Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License Recommended Citation Hargrave, Seamus Addison (2018) "An Argument for the Wider Adoption and Use of Traditional Academic Attire within Roman Catholic Church Services," Transactions of the Burgon Society: Vol. 17. https://doi.org/10.4148/2475-7799.1150 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Transactions of the Burgon Society by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Transactions of the Burgon Society, 17 (2017), pages 101–122 An Argument for the Wider Adoption and Use of Traditional Academic Attire within Roman Catholic Church Services By Seamus Addison Hargrave Introduction It has often been remarked that whilst attending Church of England or Church of Scotland services there is frequently a rich and widely used pageantry of academic regalia to be seen amongst the ministers, whilst among the Catholic counterparts there seems an almost near wilful ignorance of these meaningful articles. The response often returned when raising this issue with various members of the Catholic clergy is: ‘well, that would be a Protestant prac- tice.’ This apparent association of academic dress with the Protestant denominations seems to have led to the total abandonment of academic dress amongst the clergy and laity of the Catholic Church. -

Lutheran Identity and Regional Distinctiveness

Lutheran Identity and Regional Distinctiveness Essays and Reports 2006 Containing the essays and reports of the 23rd biennial meeting of the Lutheran Historical Conference Columbia, South Carolina October 12-14, 2006 Russell C. Kleckley, Editor Issued by The Lutheran Historical Conference Volume 22 Library of Congress Control Number 72079103 ISSN 0090-3817 The Lutheran Historical Conference is an association of Lutheran his torians, librarians and archivists in the United States and Canada. It is also open to anyone interested in the serious study of North Ameri can Lutheran history. The conference is incorporated according to the laws of the State of Missouri. Its corporate address is: 804 Seminary Place St. Louis, MO 63105-3014 In-print publications are available at the address above. Phone: 314-505-7900 email: [email protected] ©Lutheran Historical Conference 2010 An Analysis of the Changing View of the Relation ship of Doctrine and Liturgy within the WELS or The Black Geneva Piety of the Wisconsin Synod Mark Braun The topic for this paper was prompted by a comment recorded in my 2003 book, A Tale of Two Synods: Events That Led to the Split between Wjsconsjn and Mjssouri Asked in a 1997 survey what indi cators suggested that a change was taking place in The Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod, one veteran Wisconsin Synod pastor said he had observed "a growing high church tendency" in Missouri which, he said, "almost inevitably breeds doctrinal indifference."1 A 1993 grad uate of Wisconsin Lutheran Seminary called that comment "a strik ing observation in view of the current voices within our synod which advocate the liturgy as a connection with the ancient church and as a kind of bulwark against false doctrine and human innovation."2 But the comment made by that veteran pastor would not have been regarded as such a "striking observation" at all by a 1947 grad uate of Wisconsin Lutheran Seminary, or a 1958 graduate, or even a 1978 graduate. -

Vestments and Sacred Vessels Used at Mass

Vestments and Sacred Vessels used at Mass Amice (optional) This is a rectangular piece of cloth with two long ribbons attached to the top corners. The priest puts it over his shoulders, tucking it in around the neck to hide his cassock and collar. It is worn whenever the alb does not completely cover the ordinary clothing at the neck (GI 297). It is then tied around the waist. It symbolises a helmet of salvation and a sign of resistance against temptation. 11 Alb This long, white, vestment reaching to the ankles and is worn when celebrating Mass. Its name comes from the Latin ‘albus’ meaning ‘white.’ This garment symbolises purity of heart. Worn by priest, deacon and in many places by the altar servers. Cincture (optional) This is a long cord used for fastening some albs at the waist. It is worn over the alb by those who wear an alb. It is a symbol of chastity. It is usually white in colour. Stole A stole is a long cloth, often ornately decorated, of the same colour and style as the chasuble. A stole traditionally stands for the power of the priesthood and symbolises obedience. The priest wears it around the neck, letting it hang down the front. A deacon wears it over his right shoulder and fastened at his left side like a sash. Chasuble The chasuble is the sleeveless outer vestment, slipped over the head, hanging down from the shoulders and covering the stole and alb. It is the proper Mass vestment of the priest and its colour varies according to the feast. -

What They Wear the Observer | FEBRUARY 2020 | 1 in the Habit

SPECIAL SECTION FEBRUARY 2020 Inside Poor Clare Colettines ....... 2 Benedictines of Marmion Abbey What .............................. 4 Everyday Wear for Priests ......... 6 Priests’ Vestments ...... 8 Deacons’ Attire .......................... 10 Monsignors’ They Attire .............. 12 Bishops’ Attire ........................... 14 — Text and photos by Amanda Hudson, news editor; design by Sharon Boehlefeld, features editor Wear Learn the names of the everyday and liturgical attire worn by bishops, monsignors, priests, deacons and religious in the Rockford Diocese. And learn what each piece of clothing means in the lives of those who have given themselves to the service of God. What They Wear The Observer | FEBRUARY 2020 | 1 In the Habit Mother Habits Span Centuries Dominica Stein, PCC he wearing n The hood — of habits in humility; religious com- n The belt — purity; munities goes and Tback to the early 300s. n The scapular — The Armenian manual labor. monks founded by For women, a veil Eustatius in 318 was part of the habit, were the first to originating from the have their entire rite of consecrated community virgins as a bride of dress alike. Belt placement Christ. Using a veil was Having “the members an adaptation of the societal practice (dress) the same,” says where married women covered their Mother Dominica Stein, hair when in public. Poor Clare Colettines, “was a Putting on the habit was an symbol of unity. The wearing of outward sign of profession in a the habit was a symbol of leaving religious order. Early on, those the secular life to give oneself to joining an order were clothed in the God.” order’s habit almost immediately. -

The Tractarians' Political Rhetoric

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar English Faculty Research English 9-2008 The rT actarians' Political Rhetoric Robert Ellison Marshall University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/english_faculty Part of the History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Ellison, Robert H. “The rT actarians’ Political Rhetoric.” Anglican and Episcopal History 77.3 (September 2008): 221-256. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “The Tractarians’ Political Rhetoric”1 Robert H. Ellison Published in Anglican and Episcopal History 77.3 (September 2008): 221-256 On Sunday 14 July 1833, John Keble, Professor of Poetry at the University of Oxford,2 preached a sermon entitled “National Apostasy” in the Church of St Mary the Virgin, the primary venue for academic sermons, religious lectures, and other expressions of the university’s spiritual life. The sermon is remembered now largely because John Henry Newman, who was vicar of St Mary’s at the time,3 regarded it as the beginning of the Oxford Movement. Generally regarded as stretching from 1833 to Newman’s conversion to Rome in 1845, the movement was an effort to return the Church of England to her historic roots, as expressed in 1 Work on this essay was made possible by East Texas Baptist University’s Faculty Research Grant program and the Jim and Ethel Dickson Research and Study Endowment. -

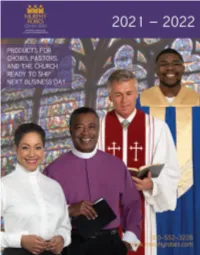

Murphycatalog.Pdf

® Welcome to our Qwick-Ship catalog of Visit www.MurphyRobes.com for our entire GUARANTEED SATISFACTION ready-to-ship items for choirs, pastors, and the collection containing hundreds of items Every item in this catalog is backed by our church - an unbelievable selection of quality available custom made. Qwick-Ship® Guarantee of Satisfaction. If you products in an incredible range of sizes you are not completely satisfied, return it, unused won't find anywhere else. and unworn, within 30 days of receipt for exchange or refund. READY TO SHIP Items in this catalog are available exactly as shown and described in sizes on referenced size chart, ready to ship next business day following receipt of order. Shipping costs vary based on speed. WHITE GLOVE® PACKAGING SERVICE With our exclusive White Glove® Packaging Service, all apparel is placed on a deluxe hanger, individually bagged and packed in a specially designed shipping container to minimize wrinkling at no extra charge. STANDARD SIZING Qwick-Ship® sizing patterns have been carefully developed to fit "average" body types with non-exceptional proportions. Order by size using item specific size charts. EXTRA SAVINGS Qwick-Ship® items are specially priced to offer extra savings over identical custom made items. Savings are shown throughout this catalog on items available custom made. AVAILABLE CUSTOM MADE To order an item in sizes, fabrics, colors or with other details than shown, ask us for assistance with custom made ordering. Allow a minimum of 8 weeks for manufacture and shipment of custom made items. We make every attempt to show fabric colors as accurately as possible.