Abbreviations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Apologetics of Tertullian by John

Identity and Religion in Roman North Africa: the apologetics of Tertullian by John Elmer P. Abad A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Graduate Department of Classics University of Toronto @ copyright by John Elmer Abad (2018) John Elmer Abad Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics University of Toronto 2018 Abstract This dissertation examines the strategies employed by Tertullian in the construction and articulation of Christian identity in the pluralistic Roman North African society. The focus will be the apologetic works of Tertullian, the Ad Martyras, the Ad Nationes and the Apologeticum written around 197 A.D. Popular biases against Christians, the Romanizing tendencies of local elites in North Africa, the marginalization of sub-elites, the influence of cultural and intellectual revolution known as the Second Sophistic Movement, and the political ideologies and propaganda of emperor Septimius Severus – all these influenced Tertullian’s attempt to construct and articulate a Christian identity capable of engaging the ever changing socio- political landscape of North African at the dawn of the third century A.D. I shall examine select areas in antiquity where identities were explored, contested and projected namely, socio- cultural, religious, and political. I have identified four spheres which I refer to as “sites” of identity construction, namely paideia, the individual, community and “religion”. Chapter One provides a brief survey of the various contexts of Tertullian’s literary production. It includes a short description of the socio-political landscape during the reign of Emperor Septimius Severus, a brief history of Christianity in Roman North Africa, an introduction to the person of Tertullian, and his place within the “apologetic” tradition. -

Life and Works of Saint Bernard, Abbot of Clairvaux

J&t. itfetnatto. LIFE AND WORKS OF SAINT BERNARD, ABBOT OF CLA1RVAUX. EDITED BY DOM. JOHN MABILLON, Presbyter and Monk of the Benedictine Congregation of S. Maur. Translated and Edited with Additional Notes, BY SAMUEL J. EALES, M.A., D.C.L., Sometime Principal of S. Boniface College, Warminster. SECOND EDITION. VOL. I. LONDON: BURNS & OATES LIMITED. NEW YORK, CINCINNATI & CHICAGO: BENZIGER BROTHERS. EMMANUBi A $ t fo je s : SOUTH COUNTIES PRESS LIMITED. .NOV 20 1350 CONTENTS. I. PREFACE TO ENGLISH EDITION II. GENERAL PREFACE... ... i III. BERNARDINE CHRONOLOGY ... 76 IV. LIST WITH DATES OF S. BERNARD S LETTERS... gi V. LETTERS No. I. TO No. CXLV ... ... 107 PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION. THERE are so many things to be said respecting the career and the writings of S. Bernard of Clairvaux, and so high are view of his the praises which must, on any just character, be considered his due, that an eloquence not less than his own would be needed to give adequate expression to them. and able labourer He was an untiring transcendently ; and that in many fields. In all his manifold activities are manifest an intellect vigorous and splendid, and a character which never magnetic attractiveness of personal failed to influence and win over others to his views. His entire disinterestedness, his remarkable industry, the soul- have been subduing eloquence which seems to equally effective in France and in Italy, over the sturdy burghers of and above of Liege and the turbulent population Milan, the all the wonderful piety and saintliness which formed these noblest and the most engaging of his gifts qualities, and the actions which came out of them, rendered him the ornament, as he was more than any other man, the have drawn him the leader, of his own time, and upon admiration of succeeding ages. -

Qualia NICHOLAS HARKNESS Harvard University, USA

Qualia NICHOLAS HARKNESS Harvard University, USA Qualia (singular, quale) are cultural emergents that manifest phenomenally as sensuous features or qualities. The anthropological challenge presented by qualia is to theorize elements of experience that are semiotically generated but apperceived as non-signs. Qualia are not reducible to a psychology of individual perceptions of sensory data, to a cultural ontology of “materiality,” or to philosophical intuitions about the subjective properties of consciousness. The analytical solution to the challenge of qualia is to con- sider tone in relation to the familiar linguistic anthropological categories of token and type. This solution has been made methodologically practical by conceptualizing qualia, in Peircean terms, as “facts of firstness” or firstness “under its form of secondness.” Inthephilosophyofmind,theterm“qualia”hasbeenusedtodescribetheineffable, intrinsic, private, and directly or immediately apprehensible experiences of “the way things seem,” which have been taken to constitute the atomic subjective properties of consciousness. This concept was challenged in an influential paper by Daniel Dennett, who argued that qualia “is a philosophers’ term which fosters nothing but confusion, and refers in the end to no properties or features at all” (Dennett 1988, 387). Dennett concluded, correctly, that these diverse elements of feeling, made sensuously present atvariouslevelsofattention,wereactuallyidiosyncraticresponsestoapperceptions of “public, relational” qualities. Qualia were, in effect, -

Vocabulary of European Philosophies, Part 2

DOSSIER Vocabulary of European Philosophies, Part 2 Following the publication of ʻSubjectʼ in RP 138, we as ʻobjectʼ. Yet as Dominique Pradelle shows, the dis- present here a trio of related entries from Barbara tinction involves ʻan etymological reawakeningʼ upon Cassin (ed.), Vocabulaire Européen des Philosophies: which Kantʼs critical revolution depended. Like that Dictionnaire des Intraduisibles (Editions du Seuil/ revolution itself, however, the precise contours of the Dictionnaires Le Robert, 2004): ʻGegenstand/Objektʼ, distinction remain in dispute. Pradelle argues that ʻter- ʻObjectʼ and ʻResʼ. Within the Vocabularyʼs reconstruc- minologically the distinction between appearance and tion of the complex, multilingual translational history thing-in-itself corresponds to the distinction between underlying the diversity of modern philosophical uses Gegenstand and Objekt in the original textʼ, thereby of ʻsubjectʼ – at once philologically meticulous and directly aligning Objekt with Ding, on the basis of philosophically polemical – the opposition of subject Kantʼs use of the expression ʻobject in itselfʼ. Others to object appears as part of only one of three main have placed more emphasis on the threefold nature of groups of meanings associated with the term ʻsubjectʼ. the chain, Gegenstand– Objekt –Ding, and hence upon Furthermore, in its most basic sense of subjectness the intermediate status of Objekt in Kantʼs discourse. ( subjectité in French, Subjektheit in German) – derived Nonetheless, this intermediate status is given its from Aristotleʼs hupokeimenon via the Latin subjec- due in Pradelleʼs brilliant exposition of the ʻdegrees of tum – the meanings of ʻsubjectʼ are shown to overlap phenomenal objectivityʼ in Kant. This also functions as with those of ʻthingʼ and ʻpragmaʼ (res and causa). -

Carroll-March-MEMHS-Meeting-1

Dear members of MEMHS, I’ve attached a chapter of my dissertation for our discussion on March 23. I am considering either revising the chapter for a book manuscript or dividing it up into several articles. Given my current career trajectory at the Sheridan Center, I am unsure which of these publication formats makes the most sense for me professionally, so I invite feedback on the paper’s potential in either of these formats (along with any other feedback you may wish to provide). I look forward to discussing the paper, and the project as a whole, with you all next Tuesday. Sincerely, Charlie Carroll CHAPTER 4 TO KNOW THE ORDINANCES OF THE HEAVENS: PREACHING MANLINESS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF PARIS When Guillaume d’Auvergne, bishop of Paris, began his sermon on the Vigil of All Saints in 1230, his words likely echoed around an empty nave. Looking up from the pulpit, he would have glanced out at a much-depleted audience, an audience likely comprised largely of students and clergy.1 This was more than a year and a half since a drunken brawl between a band of students and an innkeeper over the price of wine led to an immediate strike of students and masters, thereby endangering both the establishment of the University and the economy of the city of Paris. The dispute, which had begun in the faubourg of Saint-Marcel on Shrove Tuesday in 1229, had quickly escalated from pulling hair and striking blows to, on the following day, an all-out street riot with students armed with wooden clubs.2 The bishop, along with the prior of Saint-Marcel and 1 The sermon is included in Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS nouv. -

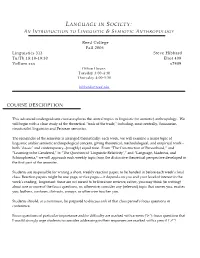

Language in Society: an Introduction to Linguistic & Semiotic Anthropology

LANGUAGE IN SOCIETY: AN INTRODUCTION TO LINGUISTIC & SEMIOTIC ANTHROPOLOGY Reed College Fall 2006 Linguistics 313 Steve Hibbard Tu/Th 18:10‐19:30 Eliot 409 Vollum xxx x7489 Office Hours: Tuesday 3:00‐4:30 Thursday 4:00‐5:30 [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION This advanced undergraduate course explores the central topics in linguistic (or semiotic) anthropology. We will begin with a close study of the theoretical ʺtools of the trade,ʺ including, most centrally, Saussurian structuralist linguistics and Peircean semiotics. The remainder of the semester is arranged thematically: each week, we will examine a major topic of linguistic and/or semiotic anthropological concern, giving theoretical, methodological, and empirical work‐‐ both ʺclassicʺ and contemporary‐‐(roughly) equal time. From “The Construction of Personhood,” and “Learning to be Gendered,” to “The Question of ‘Linguistic Relativity’,” and “Language, Madness, and Schizophrenia,” we will approach each weekly topic from the distinctive theoretical perspective developed in the first part of the semester. Students are responsible for writing a short, weekly reaction paper, to be handed in before each week’s final class. Reaction papers might be one page, or five pages—it depends on you and your level of interest in the week’s reading. Important: these are not meant to be literature reviews; rather, you may think (in writing) about one or more of the focus questions, or, otherwise, consider any (relevant) topic that moves you, excites you, bothers, confuses, distracts, annoys, or otherwise touches you. Students should, at a minimum, be prepared to discuss each of that class period’s focus questions in conference. -

Plautus, with an English Translation by Paul Nixon

^-< THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY I FOUKDED BY JAMES IXtEB, liL.D. EDITED BY G. P. GOOLD, PH.D. FORMEB EDITOBS t T. E. PAGE, C.H., LiTT.D. t E. CAPPS, ph.d., ii.D. t W. H. D. ROUSE, LITT.D. t L. A. POST, l.h.d. E. H. WARMINGTON, m.a., f.b.hist.soc. PLAUTUS IV 260 P L A U T U S WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY PAUL NIXON DKAK OF BOWDODf COLUDOB, MAin IN FIVE VOLUMES IV THE LITTLE CARTHAGINIAN PSEUDOLUS THE ROPE T^r CAMBRIDOE, MASSACHUSETTS HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD MCMLXXX American ISBN 0-674-99286-5 British ISBN 434 99260 7 First printed 1932 Reprinted 1951, 1959, 1965, 1980 v'Xn^ V Wbb Printed in Great Britain by Fletcher d- Son Ltd, Norwich CONTENTS I. Poenulus, or The Little Carthaginian page 1 II. Pseudolus 144 III. Rudens, or The Rope 287 Index 437 THE GREEK ORIGINALS AND DATES OF THE PLAYS IN THE FOURTH VOLUME In the Prologue^ of the Poenulus we are told that the Greek name of the comedy was Kapx^Sdvios, but who its author was—perhaps Menander—or who the author of the play which was combined with the Kap;^8ovios to make the Poenulus is quite uncertain. The time of the presentation of the Poenulus at ^ Rome is also imcertain : Hueffner believes that the capture of Sparta ' was a purely Plautine reference to the war with Nabis in 195 b.c. and that the Poenulus appeared in 194 or 193 b.c. The date, however, of the Roman presentation of the Pseudolus is definitely established by the didascalia as 191 b.c. -

Linguistic Anthropology in 2013: Super-New-Big

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST Linguistic Anthropology Linguistic Anthropology in 2013: Super-New-Big Angela Reyes ABSTRACT In this essay, I discuss how linguistic anthropological scholarship in 2013 has been increasingly con- fronted by the concepts of “superdiversity,” “new media,” and “big data.” As the “super-new-big” purports to identify a contemporary moment in which we are witnessing unprecedented change, I interrogate the degree to which these concepts rely on assumptions about “reality” as natural state versus ideological production. I consider how the super-new-big invites us to scrutinize various reconceptualizations of diversity (is it super?), media (is it new?), and data (is it big?), leaving us to inevitably contemplate each concept’s implicitly invoked opposite: “regular diversity,” “old media,” and “small data.” In the section on “diversity,” I explore linguistic anthropological scholarship that examines how notions of difference continue to be entangled in projects of the nation-state, the market economy, and social inequality. In the sections on “media” and “data,” I consider how questions about what constitutes lin- guistic anthropological data and methodology are being raised and addressed by research that analyzes new and old technologies, ethnographic material, semiotic forms, scale, and ontology. I conclude by questioning the extent to which it is the super-new-big itself or the contemplation about the super-new-big that produces perceived change in the world. [linguistic anthropology, superdiversity, new media, big data, -

Skeeling 1.Pdf

Musicking Tradition in Place: Participation, Values, and Banks in Bamiléké Territory by Simon Robert Jo-Keeling A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Judith T. Irvine, Chair Emeritus Professor Judith O. Becker Professor Bruce Mannheim Associate Professor Kelly M. Askew © Simon Robert Jo-Keeling, 2011 acknowledgements Most of all, my thanks go to those residents of Cameroon who assisted with or parti- cipated in my research, especially Theophile Ematchoua, Theophile Issola Missé, Moise Kamndjo, Valerie Kamta, Majolie Kwamu Wandji, Josiane Mbakob, Georges Ngandjou, Antoine Ngoyou Tchouta, Francois Nkwilang, Epiphanie Nya, Basil, Brenda, Elizabeth, Julienne, Majolie, Moise, Pierre, Raisa, Rita, Tresor, Yonga, Le Comité d’Etudes et de la Production des Oeuvres Mèdûmbà and the real-life Association de Benskin and Associa- tion de Mangambeu. Most of all Cameroonians, I thank Emanuel Kamadjou, Alain Kamtchoua, Jules Tankeu and Elise, and Joseph Wansi Eyoumbi. I am grateful to the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research for fund- ing my field work. For support, guidance, inspiration, encouragement, and mentoring, I thank the mem- bers of my dissertation committee, Kelly Askew, Judith Becker, Judith Irvine, and Bruce Mannheim. The three members from the anthropology department supported me the whole way through my graduate training. I am especially grateful to my superb advisor, Judith Irvine, who worked very closely and skillfully with me, particularly during field work and writing up. Other people affiliated with the department of anthropology at the University of Michigan were especially helpful or supportive in a variety of ways. -

Colleague, Critic, and Sometime Counselor to Thomas Becket

JOHN OF SALISBURY: COLLEAGUE, CRITIC, AND SOMETIME COUNSELOR TO THOMAS BECKET By L. Susan Carter A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of History–Doctor of Philosophy 2021 ABSTRACT JOHN OF SALISBURY: COLLEAGUE, CRITIC, AND SOMETIME COUNSELOR TO THOMAS BECKET By L. Susan Carter John of Salisbury was one of the best educated men in the mid-twelfth century. The beneficiary of twelve years of study in Paris under the tutelage of Peter Abelard and other scholars, John flourished alongside Thomas Becket in the Canterbury curia of Archbishop Theobald. There, his skills as a writer were of great value. Having lived through the Anarchy of King Stephen, he was a fierce advocate for the liberty of the English Church. Not surprisingly, John became caught up in the controversy between King Henry II and Thomas Becket, Henry’s former chancellor and successor to Theobald as archbishop of Canterbury. Prior to their shared time in exile, from 1164-1170, John had written three treatises with concern for royal court follies, royal pressures on the Church, and the danger of tyrants at the core of the Entheticus de dogmate philosophorum , the Metalogicon , and the Policraticus. John dedicated these works to Becket. The question emerges: how effective was John through dedicated treatises and his letters to Becket in guiding Becket’s attitudes and behavior regarding Church liberty? By means of contemporary communication theory an examination of John’s writings and letters directed to Becket creates a new vista on the relationship between John and Becket—and the impact of John on this martyred archbishop. -

Chapter 2 Style

Chapter 2 Style "Every apparition can be experienced in two ways. The two ways are not at random, but they are attached to the apparitions – they are derived from the nature of the apparition, from two of their characteristics: exterior – interior.” Wassily Kandinsky1 “Le style c’est l’homme même.” Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon2 Although people find it difficult to define the concept of style spontaneously, they classify each other as belonging or not belonging together by respective styles. They always do so when they see others as punk, nerd, hipster, hippie, yuppie, emo, or belonging to hip hop or the mainstream. Which succeeds more fre- quently than not! Yet, the question is how this works and why. Sociology asserts style to be either representative or constitutive of social groups, or else both.3 However, there is consensus in all of sociology that social 1 Kandinsky 1973 (1926), p. 13, my translation. 2 Cited after Saisselin 1958. 3 Modernist sociology regards differences in endowment (financial and cultural capital) as being constitutive for forming social groups; style is merely representative of social groups (for exam- ple, the Birmingham School in its analysis of British youth cultures [Hebdige 1988]). In contrast, in the postmodern variant of sociology, the group style is understood as the constituent charac- teristic of the group; it is only by showing a style, that groups can come into being and are able to persist; other socio-cultural characteristics, for example the endowment with capital, play no or only a secondary role. Bourdieu (1982) marks the transition from modernism to postmodernism, 48 Part 1: Culture of Dissimiarity groups and their style form an inseparable entity. -

Black Semiosis: Young Liberian Transnationals Mediating Black Subjectivity and Black Heterogeneity Krystal A

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 1-1-2015 Black Semiosis: Young Liberian Transnationals Mediating Black Subjectivity and Black Heterogeneity Krystal A. Smalls University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the African American Studies Commons, Anthropological Linguistics and Sociolinguistics Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Smalls, Krystal A., "Black Semiosis: Young Liberian Transnationals Mediating Black Subjectivity and Black Heterogeneity" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2022. http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2022 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2022 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Black Semiosis: Young Liberian Transnationals Mediating Black Subjectivity and Black Heterogeneity Abstract From the colonization of the “Dark Continent,” to the global industry that turned black bodies into chattel, to the total absence of modern Africa from most American public school curricula, to superfluous representations of African primitivity in mainstream media, to the unflinching state-sanctioned murders of unarmed black people in the Americas, antiblackness and anti-black racism have been part and parcel to modernity, swathing centuries and continents, and seeping into the tiny spaces and moments that constitute social reality for most black-identified