Tolerance in Swami Vivekānanda's Neo-Hinduism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REL 3337 Religions in Modern India Vasudha Narayanan

1 REL 3337 Religions in Modern India Vasudha Narayanan, Distinguished Professor, Religion [email protected] (Please use email for all communications) Office hours: Wednesdays 2:00-3:00 pm and by appointment Credits: 3 credit hours Course Term: Fall 2018 Class Meeting Time: M Period 9 (4:05 PM - 4:55 PM) AND 0134 W Period 8 - 9 (3:00 PM - 4:55 PM) In this course, you will learn about the religious and cultural diversity in the sub-continent, and understand the history of religion starting with the colonial period. We will study the major religious thinkers, many of whom had an impact on the political history of India. We will study the rites-of-passage, connections between food and religion, places of worship, festivals, gurus, as well as the close connections between religion and politics in many of these traditions. The religious traditions we will examine and intellectually engage with are primarily Hinduism, Jainism, Sikhism, as well as Christianity and Islam in India. We will strike a balance between a historical approach and a thematic one whereby sacraments, rituals, and other issues and activities that are religiously important for a Hindu family can be explained. This will include discussion of issues that may not be found in traditional texts, and I will supplement the readings with short journal and magazine articles, videos, and slides. The larger questions indirectly addressed in the course will include the following: Are the Indian concepts of "Hinduism" and western concepts of "religion" congruent? How ha colonial scholarship and assumptions shaped our understanding of South Asian Hindus and the "minority traditions" as distinct religious and social groups, blurring regional differences? How are gender issues made manifest in rituals? How does religious identity influence political and social behavior? How do Hindus in South Asia differentiate among themselves? Course Goals When you complete this course, you will be able to: 1. -

Hinduism Around the World

Hinduism Around the World Numbering approximately 1 billion in global followers, Hinduism is the third-largest religion in the world. Though more than 90 percent of Hindus live on the Indian subcontinent (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Bhutan), the Hindu diaspora’s impact can still be felt today. Hindus live on every continent, and there are three Hindu majority countries in the world: India, Nepal, and Mauritius. Hindu Diaspora Over Centuries Hinduism began in the Indian subcontinent and gradually spread east to what is now contemporary Southeast Asia. Ancient Hindu cultures thrived as far as Cambodia, Thailand, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Indonesia. Some of the architectural works (including the famous Angkor Wat temple in Cambodia) still remain as vestiges of Hindu contact. Hinduism in Southeast Asia co-worshipped with Buddhism for centuries. However, over time, Buddhism (and later Islam in countries such as Indonesia) gradually grew more prominent. By the 10th century, the practice of Hinduism in the region had waned, though its influence continued to be strong. To date, Southeast Asia has the two highest populations of native, non-Indic Hindus: the Balinese Hindus of Indonesia and the Cham people of Vietnam. The next major migration took place during the Colonial Period, when Hindus were often taken as indentured laborers to British and Dutch colonies. As a result, Hinduism spread to the West Indies, Fiji, Copyright 2014 Hindu American Foundation Malaysia, Mauritius, and South Africa, where Hindus had to adjust to local ways of life. Though the Hindu populations in many of these places declined over time, countries such as Guyana, Mauritius, and Trinidad & Tobago, still have significant Hindu populations. -

Hindu Responses to Religious Diversity and the Nature of Post-Mortem Progress

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo Hindu Responses to Religious Diversity and the Nature of Post-Mortem Progress The last two hundred years of Hindu–Christian encounters have produced distinctive forms of Hindu thought which, while often rooted in the broad philosophical-cultural continuities of Vedic outlooks, grappled with, on the one hand, the colonial pressures of European modernity, and, on the other hand, the numerous critiques by Christian theologians and missionaries on the Hindu life-worlds. Thus, the spectrum of Hindu responses from Raja Rammohun Roy through Swami Vivekananda to S. Radhakrishnan demonstrates attempts to creatively engage with Christian representations of Hindu belief and practice, by accepting their prima facie validity at one level while negating their adequacy at another. For instance, these figures of neo-Hinduism accepted that such ‘corruptions’ as Hinduism’s alleged idol- worship, anti-worldly ethic, caste-based distinctions and the like were all too visible on the socio-cultural domain, while they formulated revamped Vedic or Vedantic visions within which these were to be either rejected as excrescences or given demythologised interpretations. In Swami Vivekananda, we find on some occasions a more strident rejection of certain aspects of western civilization as steeped in materialist ‘excesses’ which needed to be purged through the light of Vedantic wisdom. Through such hermeneutical processes of retrieval, often carried out within contexts structured by British colonialism, these figures were able to offer forms of Hinduism that were signifiers not of the Oriental depravity that the British administrators, scholars and missionaries had claimed to perceive on the Indian landscapes but of a spiritual depth that transcended national, cultural and ethnic boundaries. -

Metro Railway Kolkata Presentation for Advisory Board of Metro Railways on 29.6.2012

METRO RAILWAY KOLKATA PRESENTATION FOR ADVISORY BOARD OF METRO RAILWAYS ON 29.6.2012 J.K. Verma Chief Engineer 8/1/2012 1 Initial Survey for MTP by French Metro in 1949. Dum Dum – Tollygunge RTS project sanctioned in June, 1972. Foundation stone laid by Smt. Indira Gandhi, the then Prime Minister of India on December 29, 1972. First train rolled out from Esplanade to Bhawanipur (4 km) on 24th October, 1984. Total corridor under operation: 25.1 km Total extension projects under execution: 89 km. June 29, 2012 2 June 29, 2012 3 SEORAPFULI BARRACKPUR 12.5KM SHRIRAMPUR Metro Projects In Kolkata BARRACKPUR TITAGARH TITAGARH 10.0KM BARASAT KHARDAH (UP 17.88Km) KHARDAH 8.0KM (DN 18.13Km) RISHRA NOAPARA- BARASAT VIA HRIDAYPUR PANIHATI AIRPORT (UP 15.80Km) (DN 16.05Km)BARASAT 6.0KM SODEPUR PROP. NOAPARA- BARASAT KONNAGAR METROMADHYAMGRAM EXTN. AGARPARA (UP 13.35Km) GOBRA 4.5KM (DN 13.60Km) NEW BARRACKPUR HIND MOTOR AGARPARA KAMARHATI BISARPARA NEW BARRACKPUR (UP 10.75Km) 2.5KM (DN 11.00Km) DANKUNI UTTARPARA BARANAGAR BIRATI (UP 7.75Km) PROP.BARANAGAR-BARRACKPORE (DN 8.00Km) BELGHARIA BARRACKPORE/ BELA NAGAR BIRATI DAKSHINESWAR (2.0Km EX.BARANAGAR) BALLY BARANAGAR (0.0Km)(5.2Km EX.DUM DUM) SHANTI NAGAR BIMAN BANDAR 4.55KM (UP 6.15Km) BALLY GHAT RAMKRISHNA PALLI (DN 6.4Km) RAJCHANDRAPUR DAKSHINESWAR 2.5KM DAKSHINESWAR BARANAGAR RD. NOAPARA DAKSHINESWAR - DURGA NAGAR AIRPORT BALLY HALT NOAPARA (0.0Km) (2.09Km EX.DMI) HALDIRAM BARANAGAR BELUR JESSOR RD DUM DUM 5.0KM DUM DUM CANT. CANT 2.60KM NEW TOWN DUM DUM LILUAH KAVI SUBHAS- DUMDUM DUM DUM ROAD CONVENTION CENTER DUM DUM DUM DUM - BELGACHIA KOLKATA DASNAGAR TIKIAPARA AIRPORT BARANAGAR HOWRAH SHYAM BAZAR RAJARHAT RAMRAJATALA SHOBHABAZAR Maidan BIDHAN NAGAR RD. -

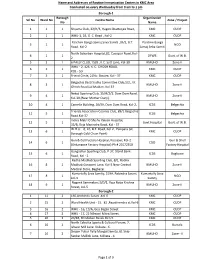

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area Conducted on every Wednesday from 9 am to 1 pm Borough-1 Borough Organization Srl No Ward No Centre Name Zone / Project No Name 1 1 1 Shyama Club, 22/H/3, Hagen Chatterjee Road, KMC CUDP 2 1 1 WHU-1, 1B, G. C. Road , Kol-2 KMC CUDP Paschim Banga Samaj Seva Samiti ,35/2, B.T. Paschim Banga 3 1 1 NGO Road, Kol-2 Samaj Seba Samiti North Subarban Hospital,82, Cossipur Road, Kol- 4 1 1 DFWB Govt. of W.B. 2 5 2 1 6 PALLY CLUB, 15/B , K.C. Sett Lane, Kol-30 KMUHO Zone-II WHU - 2, 126, K. C. GHOSH ROAD, 6 2 1 KMC CUDP KOL - 50 7 3 1 Friend Circle, 21No. Bustee, Kol - 37 KMC CUDP Belgachia Basti Sudha Committee Club,1/2, J.K. 8 3 1 KMUHO Zone-II Ghosh Road,Lal Maidan, Kol-37 Netaji Sporting Club, 15/H/2/1, Dum Dum Road, 9 4 1 KMUHO Zone-II Kol-30,(Near Mother Diary). 10 4 1 Camelia Building, 26/59, Dum Dum Road, Kol-2, ICDS Belgachia Friends Association Cosmos Club, 89/1 Belgachia 11 5 1 ICDS Belgachia Road.Kol-37 Indira Matri O Shishu Kalyan Hospital, 12 5 1 Govt.Hospital Govt. of W.B. 35/B, Raja Manindra Road, Kol - 37 W.H.U. - 6, 10, B.T. Road, Kol-2 , Paikpara (at 13 6 1 KMC CUDP Borough Cold Chain Point) Gun & Cell Factory Hospital, Kossipur, Kol-2 Gun & Shell 14 6 1 CGO (Ordanance Factory Hospital) Ph # 25572350 Factory Hospital Gangadhar Sporting Club, P-37, Stand Bank 15 6 1 ICDS Bagbazar Road, Kol - 2 Radha Madhab Sporting Club, 8/1, Radha 16 8 1 Madhab Goswami Lane, Kol-3.Near Central KMUHO Zone-II Medical Store, Bagbazar Kumartully Seva Samity, 519A, Rabindra Sarani, Kumartully Seva 17 8 1 NGO kol-3 Samity Nagarik Sammelani,3/D/1, Raja Naba Krishna 18 9 1 KMUHO Zone-II Street, kol-5 Borough-2 1 11 2 160,Arobindu Sarani ,Kol-6 KMC CUDP 2 15 2 Ward Health Unit - 15. -

SWAMI YOGANANDA and the SELF-REALIZATION FELLOWSHIP a Successful Hindu Countermission to the West

STATEMENT DS213 SWAMI YOGANANDA AND THE SELF-REALIZATION FELLOWSHIP A Successful Hindu Countermission to the West by Elliot Miller The earliest Hindu missionaries to the West were arguably the most impressive. In 1893 Swami Vivekananda (1863 –1902), a young disciple of the celebrated Hindu “avatar” (manifestation of God) Sri Ramakrishna (1836 –1886), spoke at the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago and won an enthusiastic American following with his genteel manner and erudite presentation. Over the next few years, he inaugurated the first Eastern religious movement in America: the Vedanta Societies of various cities, independent of one another but under the spiritual leadership of the Ramakrishna Order in India. In 1920 a second Hindu missionary effort was launched in America when a comparably charismatic “neo -Vedanta” swami, Paramahansa Yogananda, was invited to speak at the International Congress of Religious Liberals in Boston, sponsored by the Unitarian Church. After the Congress, Yogananda lectured across the country, spellbinding audiences with his immense charm and powerful presence. In 1925 he established the headquarters for his Self -Realization Fellowship (SRF) in Los Angeles on the site of a former hotel atop Mount Washington. He was the first Eastern guru to take up permanent residence in the United States after creating a following here. NEO-VEDANTA: THE FORCE STRIKES BACK Neo-Vedanta arose partly as a countermissionary movement to Christianity in nineteenth -century India. Having lost a significant minority of Indians (especially among the outcast “Untouchables”) to Christianity under British rule, certain adherents of the ancient Advaita Vedanta school of Hinduism retooled their religion to better compete with Christianity for the s ouls not only of Easterners, but of Westerners as well. -

Downloads\0673558-Eq-130916-Theology of Religions Instrument Ja__Ljf Final 22 Dec 2015.Doc 20/09/2016 ASTLEY-FRANCIS THEOLOGY of RELIGIONS INDEX 2

Original citation: Astley, Jeff and Francis, Leslie J.. (2016) Introducing the Astley–Francis Theology of Religions Index : construct validity among 13- to 15-year-old students. Journal of Beliefs & Values, 37 (1). pp. 29-39. Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/81708 Copyright and reuse: The Warwick Research Archive Portal (WRAP) makes this work by researchers of the University of Warwick available open access under the following conditions. Copyright © and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in WRAP has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. Publisher’s statement: “This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in International . Journal of Beliefs & Values on 07/03/2016 available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/13617672.2016.1141527 A note on versions: The version presented here may differ from the published version or, version of record, if you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the ‘permanent WRAP URL’ above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. -

Introduction

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction The Invention of an Ethnic Nationalism he Hindu nationalist movement started to monopolize the front pages of Indian newspapers in the 1990s when the political T party that represented it in the political arena, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP—which translates roughly as Indian People’s Party), rose to power. From 2 seats in the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Indian parliament, the BJP increased its tally to 88 in 1989, 120 in 1991, 161 in 1996—at which time it became the largest party in that assembly—and to 178 in 1998. At that point it was in a position to form a coalition government, an achievement it repeated after the 1999 mid-term elections. For the first time in Indian history, Hindu nationalism had managed to take over power. The BJP and its allies remained in office for five full years, until 2004. The general public discovered Hindu nationalism in operation over these years. But it had of course already been active in Indian politics and society for decades; in fact, this ism is one of the oldest ideological streams in India. It took concrete shape in the 1920s and even harks back to more nascent shapes in the nineteenth century. As a movement, too, Hindu nationalism is heir to a long tradition. Its main incarnation today, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS—or the National Volunteer Corps), was founded in 1925, soon after the first Indian communist party, and before the first Indian socialist party. -

The Inner Light: the Beatles, India, Gurus, and the Legacy

The Inner Light: The Beatles, India, Gurus, and the Legacy John Covach Institute for Popular Music, University of Rochester Arthur Satz Department of Music Eastman School of Music Main Points The Beatles’ “road to India” is mostly navigated by George Harrison John Lennon was also enthusiastic, Paul somewhat, Ringo not so much Harrison’s “road to India” can be divided into two kinds of influence: Musical influences—the actual sounds and structures of Indian music Philosophical and spiritual influences—elements that influence lyrics and lifestyle The musical influences begin in April 1965, become focused in fall 1966, and extend to mid 1968 The philosophical influences begin in late 1966 and continue through the rest of Harrison’s life Note: Harrison began using LSD in the spring of 1965 and discontinued in August 1967 Songs by other Beatles, Lennon especially, also reflect Indian influences The Three “Indian” songs of George Harrison “Love You To” recorded April 1966, released on Revolver, August 1966 “Within You Without You” recorded March, April 1967, released on Sgt Pepper, June 1967 “The Inner Light” recorded January, February 1968, released as b-side to “Lady Madonna,” March 1968 Three Aspects of “Indian” characteristics Use of some aspect of Indian philosophy or spirituality in the lyrics Use of Indian musical instruments Use of Indian musical features (rhythmic patterns, drone, texture, melodic elements) Musical Influences Ravi Shankar is principal influence on Harrison, though he does not enter the picture until mid 1966 April 1965: Beatles film restaurant scene for Help! Harrison falls in love with the sitar, buys one cheap Summer 1965: Beatles in LA hear about Shankar from McGuinn, Crosby (meet Elvis, discuss Yogananda) October 1965: “Norwegian Wood” recorded, released in December on Rubber Soul. -

Shri Sai Baba

Sai Mandir USA 1889 Grand Avenue, Baldwin, NY 11510, USA Designed & Developed by : Praveen Batchu http://www.imagicapps.com SHRI SAI SATCHARITA OR THE WONDERFUL LIFE AND TEACHINGS OF SHRI SAI BABA Adapted from the original Marathi book by Hemadpant by Nagesh Vasudev Gunaji, B.A., L.L.B. 227, Thalakwadi, Belgaum. changes to the current version to make a easy reading experience to American devotees. This book is available for free to all devotees. Published by Kashinath Sitaram Pathak, Court Receiver, Shri Sai Baba Sansthan, Shirdi, ‘Sai Niketan’, 804-B, Dr. Ambedkar Road, Dadar, Bombay 400 014. This book will be available for sale at the following places: (1) Court Receiver, Shri Sai Sansthan, Shirdi, P.O. Shirdi, (Dist. Ahmednagar). (2) Shri Kashinath Sitaram Pathak, Court Receiver, Shri Sai Baba Sansthan, Shirdi, “Sai Niketan”, 804-B, Dr. Ambedkar Road, Dadar, Bombay 400 014. Copyright reserved by the Sansthan Printed by N.D. Rege, at Mohan Printery, 425-A Mogul Lane, Mahim, Bombay 400 016 and Published by Shri Kashinath Sitaram Pathak, Court Receiver, Shri Sai Baba Sansthan, Shirdi, “Sai Niketan”, 804-B, Dr. Ambedkar Road, Dadar, Bombay 400 014. DEDICATION “Whosoever offers to me, with love or devotion, a leaf, a flower, a fruit or water, that offering of love of the pure and self-controlled man is willingly and readily accepted by me.” Lord Shri Krishna in Bhagavad Gita, IX - 26 To Shri Sai Baba The Antaryamin This work with myself Editor : Laura Keller New York, USA SHRI SAI SATCHARITA CONTENTS Preface by the author Preface to the second edition Preface by Shri N.A. -

The Contemplative Life – Most Revered Swami Atmasthanandaji Maharaj

The Contemplative Life – Most Revered Swami Atmasthanandaji Maharaj. Most Revered Swami Atmasthanandaji Maharaj was the 15th President of the world -wide Ramakrishna Math and Ramakrishna Mission. In this article Most Revered Maharaj provides guidelines on how to lead a contemplative life citing many personal reminiscences of senior monks of the Ramakrishna tradition who lead inspiring spiritual lives. Source : Prabuddha Bharata – Jan 2007 SADHAN-BHAJAN or spiritual practice – japa, prayer and meditation – should play a very vital role in the lives of all. This is a sure way to peace despite all the hindrances that one has to face in daily life. The usual complaint is that it is very difficult to lead an inward life of sadhana or contemplation amidst the rush and bustle of everyday life. But with earnestness and unshakable determination one is sure to succeed. Sri Ramakrishna has said that a devotee should hold on to the feet of the Lord with the right hand and clear the obstacles of everyday life with the other. There are two primary obstacles to contemplative life. The first one is posed by personal internal weaknesses. One must have unswerving determination to surmount these. The second one consists of external problems. These we have to keep out, knowing them to be harmful impediments to our goal. For success in contemplative life, one needs earnestness and regularity. Study of the scriptures, holy company, and quiet living help develop our inner lives. I have clearly seen that all the great swamis of our Order have led a life of contemplation even in the midst of great distractions. -

"Paã±Ca Viveka" and Thomas Aquinas' "Quinque Viae" in the Light of Today's

Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 23 Article 9 January 2010 Vidyaranya Swami's "pañca viveka" and Thomas Aquinas' "quinque viae" in the Light of Today's Science Klaus K. Klostermaier Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Klostermaier, Klaus K. (2010) "Vidyaranya Swami's "pañca viveka" and Thomas Aquinas' "quinque viae" in the Light of Today's Science," Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies: Vol. 23, Article 9. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1461 The Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies is a publication of the Society for Hindu-Christian Studies. The digital version is made available by Digital Commons @ Butler University. For questions about the Journal or the Society, please contact [email protected]. For more information about Digital Commons @ Butler University, please contact [email protected]. Klostermaier: Vidyaranya Swami's "pañca viveka" and Thomas Aquinas' "quinque viae" in the Light of Today's Science 1 Vidyara:Q.ya SwamI's paiica viveka and Thomas Aquinas' quinque viae in the Light of Today's Science Klaus K. Klostermaier Professor Emeritus, University of Manitoba "Brahman cannot be seen, but through entries under the term 'proofs of god.' Its reasoning1 and revelatio~ its extremely long Wikipedia article ranges widely existence can be ascertained. " and includes Christian and Hindu proofs of the Vidyara:r;tya (1268- 1350), Pancadasi VI, existence of God as well as traditional and 1673 contemporary arguments against it. It is not my intention in this paper to roll out "From the effects of God it can be the entire problematic connected with the issue of demonstrated that God is." 'proofs of god' or to deal with the historical Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), Summa contexts to the Pancadasf and the Summa theologica I, 2, 2 ad 34 .