The Contemplative Life – Most Revered Swami Atmasthanandaji Maharaj

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sage of Vasishtha Guha - the Last Phase

THE SAGE OF VASISHTHA GUHA - THE LAST PHASE by SWAMI NIRVEDANANDA THE SAGE OF VASISHTHA GUHA - THE LAST PHASE by SWAMI NIRVEDANANDA Published By SWAMI NIRVEDANANDA VILLAGE : KURTHA, GHAZIPUR - - 233 001. (C) SHRI PURUSHOTTAMANANDA TRUST First Edition 1975 Copies can be had from : SHRI M. P. SRIVASTAVA, 153 RAJENDRANAGAR, LUCKNOW - 226 004. Printed at SEVAIi PRESS, Bombay-400 019 (India) DEDICATION What is Thine own, 0 Master! F offer unto Thee alone c^'-q R;q q^ II CONTENTS Chapter. Page PREFACE 1 THE COMPASSIONATE GURU 1 II A SANNYASA CEREMONY ... ii 111 PUBLICATION OF BIOGRAPHY ... ... 6 IV ARDHA-KUMBHA AT PRAYAG ... ... 8 V A NEW KUTIR ... 12 VI ON A TOUR TO THE SOUTH 13 VII OMKARASHRAMA 10 VIII TOWARDS KANYAKUMARI ... ... 18 IX THE RETURN JOURNEY ... ... 23 X THE CRUISE ON THE PAMPA ... ... 24 XI VISIT TO THE HOUSE OF BIRTH ... ... 27 XII GOOD-BYE TO THE SOUTH ... ... 28 XLII RISHIKESH - VASISHTHA GUHA ... ... 29 XIV TWO SANNYASA CEREMONIES ... 30 XV AT THE DEATH-BED OF A DISCIPL E ... 32 XVI THE LAST TOUR ... 35 XVII MAHASAMADHI & AFTER ... 30 XVIII VASISHTHA GUHA ASHRAMA TODAY ... 48 APPENDIX ... 50 Tre lace T HE Sage of Vasishtha Guha, the Most Revered Skvami Puru- shottamanandaji Maharaj, attained Mahasamadhi in the year 1961. This little volume covers the last two years of his sojourn on earth and is being presented to the readers as a com- plement to "The Life of Swami Purushottamananda," published in 1959. More than twelve years have elapsed since Swamiji's Mahasamadhi and it is only now that details could be collected and put in the form of a book. -

Sri Ramakrishna Math

Sri Ramakrishna Math 31, Ramakrishna Math Road, Mylapore, Chennai - 600 004, India & : 91-44-2462 1110 / 9498304690 email: [email protected] / website: www.chennaimath.org Catalogue of some of our publications… Buy books online at istore.chennaimath.org & ebooks at www.vedantaebooks.org Some of Our Publications... Sri Ramakrishna the Great Master Swami Saradananda / Tr. Jagadananda This book is the most comprehensive, authentic and critical estimate of the life, sadhana, and teachings of Sri Ramakrishna. It is an English translation of Sri Sri Ramakrishna Lila-prasanga written in Bengali by Swami Saradananda, a direct disciple of Sri Ramakrishna and who is deemed an authority both as a philosopher and as a biographer. His biographical narrative of Sri Ramakrishna Volume 1 is based on his firsthand observations, assiduous collection of material from Pages 788 | Price ` 200 different authentic sources, and patient sifting of evidence. Known for his vast Volume 2 erudition, spirit of rational enquiry and far-reaching spiritual achievements, Pages 688 | Price ` 225 he has interspersed the narrative with lucid interpretations of various religious cults, mysticism, philosophy, and intricate problems connected with the theory and practice of religion. Translated faithfully into English by Swami Jagadananda, who was a disciple of the Holy Mother, this book may be ranked as one of the best specimens in hagiographic literature. The book also contains a chronology of important events in the life of Sri Ramakrishna, his horoscope, and a short but beautiful article by Swami Nirvedananda on the book and its author. This firsthand, authentic book is a must- read for everyone who wishes to know about and contemplate on the life of Sri Ramakrishna. -

Sri Ramakrishna & His Disciples in Orissa

Preface Pilgrimage places like Varanasi, Prayag, Haridwar and Vrindavan have always got prominent place in any pilgrimage of the devotees and its importance is well known. Many mythological stories are associated to these places. Though Orissa had many temples, historical places and natural scenic beauty spot, but it did not get so much prominence. This may be due to the lack of connectivity. Buddhism and Jainism flourished there followed by Shaivaism and Vainavism. After reading the lives of Sri Chaitanya, Sri Ramakrishna, Holy Mother and direct disciples we come to know the importance and spiritual significance of these places. Holy Mother and many disciples of Sri Ramakrishna had great time in Orissa. Many are blessed here by the vision of Lord Jagannath or the Master. The lives of these great souls had shown us a way to visit these places with spiritual consciousness and devotion. Unless we read the life of Sri Chaitanya we will not understand the life of Sri Ramakrishna properly. Similarly unless we study the chapter in the lives of these great souls in Orissa we will not be able to understand and appreciate the significance of these places. If we go on pilgrimage to Orissa with same spirit and devotion as shown by these great souls, we are sure to be benefited spiritually. This collection will put the light on the Orissa chapter in the lives of these great souls and will inspire the devotees to read more about their lives in details. This will also help the devotees to go to pilgrimage in Orissa and strengthen their devotion. -

Indian Political Thaught Unit Iii

INDIAN POLITICAL THAUGHT UNIT III Paper Code – 18MPO22C Class – I M.A POLITICAL SCIENCE Faculty Name – M.Deepa Contact No. 9489345565 RAJA RAM MOHAN ROY LIFE AND TIME OF RAJA RAM MOHAN ROY ✓ He was born in 1772, in Radhanagar village in Murshidabad District of West Bengal. ✓ Bengal, after 1765, came under British East India company, Colonial rule, centred in Kolkata, was expanding in all parts of India. Limited constitutional reforms, capitalist economy, English education, etc were being introduced. ✓ Studied Arbic & Persian in Patna, Sanskrit in Banaras, English later on a company official, Besides Bengali and Sanskrit, Roy had mastered Arabic, Persian, Hebrew, Greek, Latin and many other leading language. ✓ Besides Hinduism, he learnt Islam, Buddhism, and Christianity. Through this he developed belief in unity of God, and Religion. INFLUENCE ✓ John Locke, Bentham , David Hume, ✓ 1830 he went to England with many purposes-one was requesting more pension to Mughal King Akkbar-II Who gave him the title of Raja. He died there on 1833. HIS RELIGIOUS THOUGHT ✓ Influenced by Enlightenment spirit and Utilitarian Liberalism. ✓ Human have God gifted sense of reason and intellect to assess the trust and social utility in religious doctrine, no need for any intermediary-priest, Pandit UNITY IN ALL RELIGION ✓ Universal Supreme being, Existence of soul, Life after death ✓ But, all religion suffer from dogmas, ritualism, irrational beliefs & Practices; to benefit the intermediaries and keep people in dark ✓ Hinduism suffered from polytheism, idolatry, superstitions, ritualism. ✓ Ancient purity of Hindu religion-as contained in Veda & Upanishad-lost in faulty interpretation, orthodoxy, conservatism in the wake of tyrannical and despotic Muslim and Rajput Rules. -

Reminiscences of Swami Prabuddhananda

Reminiscences of Swami Prabuddhananda India 2010 These precious memories of Swami Prabuddhanandaji are unedited. Since this collection is for private distribution, there has been no attempt to correct or standardize the grammar, punctuation, spelling or formatting. The charm is in their spontaneity and the heartfelt outpouring of appreciation and genuine love of this great soul. May they serve as an ongoing source of inspiration. Memories of Swami Prabuddhananda MEMORIES OF SWAMI PRABUDDHANANDA RAMAKRISHNA MATH Phone PBX: 033-2654- (The Headquarters) 1144/1180 P.O. BELUR MATH, DIST: FAX: 033-2654-4346 HOWRAH Email: [email protected] WEST BENGAL : 711202, INDIA Website: www.belurmath.org April 27, 2015 Dear Virajaprana, I am glad to receive your e-mail of April 24, 2015. Swami Prabuddhanandaji and myself met for the first time at the Belur Math in the year 1956 where both of us had come to receive our Brahmacharya-diksha—he from Bangalore and me from Bombay. Since then we had close connection with each other. We met again at the Belur Math in the year 1960 where we came for our Sannyasa-diksha from Most Revered Swami Sankaranandaji Maharaj. I admired his balanced approach to everything that had kept the San Francisco centre vibrant. In 2000 A.D. he had invited me to San Francisco to attend the Centenary Celebrations of the San Francisco centre. He took me also to Olema and other retreats on the occasion. Once he came just on a visit to meet the old Swami at the Belur Math. In sum, Swami Prabuddhanandaji was an asset to our Order, and his leaving us is a great loss. -

Swami Vivekananda's Mission and Teachings

LIFE IS A VOYAGE1: Swami Vivekananda’s Mission and Teachings – A Cognitive Linguistic Analysis with Reference to the Theme of HOMECOMING Suren Naicker Abstract This study offers an in-depth analysis of the well-known LIFE AS A JOURNEY conceptual metaphor, applied to Vivekananda’s mission as he saw it, as well as his teachings. Using conceptual metaphor theory as a framework, Vivekananda’s Complete Works were manually and electronically mined for examples of how he conceptualized his own mission, which culminated in the formation of the Ramakrishna Math and Mission, a world-wide neo-Hindu organization. This was a corpus-based study, which starts with an overview of who Vivekananda was, including a discussion of his influence on other neo- Hindu leaders. This study shows that Vivekananda had a very clear understanding of his life’s mission, and saw himself almost in a messianic role, and was glad when his work was done, so he could return to his Cosmic ‘Home’. He uses these key metaphors to explain spiritual life in general as well as his own life’s work. Keywords: Vivekananda; neo-Hinduism; Ramakrishna; cognitive linguistics; conceptual metaphor theory 1 As is convention in the field of Cognitive Semantics, conceptual domains are written in UPPER CASE. Alternation Special Edition 28 (2019) 247 – 266 247 Print ISSN 1023-1757; Electronic ISSN: 2519-5476; DOI https://doi.org/10.29086/2519-5476/2019/sp28.4a10 Suren Naicker Introduction This article is an exposition of two conceptual metaphors based on the Complete Works2 of Swami Vivekananda. Conceptual metaphor theory is one of the key theories within the field of cognitive linguistics. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Adi Sankaracharya's VIVEKACHUDAMANI

Adi Sankaracharya's VIVEKACHUDAMANI Translated by Swami Madhavananda Published by Advaita Ashram, Kolkatta 1. I bow to Govinda, whose nature is Bliss Supreme, who is the Sadguru, who can be known only from the import of all Vedanta, and who is beyond the reach of speech and mind. 2. For all beings a human birth is difficult to obtain, more so is a male body; rarer than that is Brahmanahood; rarer still is the attachment to the path of Vedic religion; higher than this is erudition in the scriptures; discrimination between the Self and not-Self, Realisation, and continuing in a state of identity with Brahman – these come next in order. (This kind of) Mukti (Liberation) is not to be attained except through the well- earned merits of a hundred crore of births. 3. These are three things which are rare indeed and are due to the grace of God – namely, a human birth, the longing for Liberation, and the protecting care of a perfected sage. 4. The man who, having by some means obtained a human birth, with a male body and mastery of the Vedas to boot, is foolish enough not to exert himself for self-liberation, verily commits suicide, for he kills himself by clinging to things unreal. 5. What greater fool is there than the man who having obtained a rare human body, and a masculine body too, neglects to achieve the real end of this life ? 6. Let people quote the Scriptures and sacrifice to the gods, let them perform rituals and worship the deities, but there is no Liberation without the realisation of one’s identity with the Atman, no, not even in the lifetime of a hundred Brahmas put together. -

Ramakrishna-Vedanta in Southern California: from Swami Vivekananda to the Present

Ramakrishna-Vedanta in Southern California: From Swami Vivekananda to the Present Appendix I: Ramakrishna-Vedanta Swamis in Southern California and Affiliated Centers (1899-2017) Appendix II: Ramakrishna-Vedanta Swamis (1893-2017) Appendix III: Presently Existing Ramakrishna-Vedanta Centers in North America (2017) Appendix IV: Ramakrishna-Vedanta Swamis from India in North America (1893-2017) Bibliography Alphabetized by Abbreviation Endnotes Appendix 12/13/2020 Page 1 Ramakrishna-Vedanta in Southern California: From Swami Vivekananda to the Present Appendix I: Ramakrishna Vedanta Swamis Southern California and Affiliated Centers (1899-2017)1 Southern California Vivekananda (1899-1900) to India Turiyananda (1900-02) to India Abhedananda (1901, 1905, 1913?, 1914-18, 1920-21) to India—possibly more years Trigunatitananda (1903-04, 1911) Sachchidananda II (1905-12) to India Prakashananda (1906, 1924)—possibly more years Bodhananda (1912, 1925-27) Paramananda (1915-23) Prabhavananda (1924, 1928) _______________ La Crescenta Paramananda (1923-40) Akhilananda (1926) to Boston _______________ Prabhavananda (Dec. 1929-July 1976) Ghanananda (Jan-Sept. 1948, Temporary) to London, England (Names of Assistant Swamis are indented) Aseshananda (Oct. 1949-Feb. 1955) to Portland, OR Vandanananda (July 1955-Sept. 1969) to India Ritajananda (Aug. 1959-Nov. 1961) to Gretz, France Sastrananda (Summer 1964-May 1967) to India Budhananda (Fall 1965-Summer 1966, Temporary) to India Asaktananda (Feb. 1967-July 1975) to India Chetanananda (June 1971-Feb. 1978) to St. Louis, MO Swahananda (Dec. 1976-2012) Aparananda (Dec. 1978-85) to Berkeley, CA Sarvadevananda (May 1993-2012) Sarvadevananda (Oct. 2012-) Sarvapriyananda (Dec. 2015-Dec. 2016) to New York (Westside) Resident Ministers of Affiliated Centers: Ridgely, NY Vivekananda (1895-96, 1899) Abhedananda (1899) Turiyananda (1899) _______________ (Horizontal line means a new organization) Atmarupananda (1997-2004) Pr. -

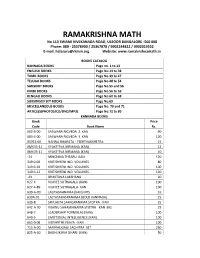

Halasuru Math Book List

RAMAKRISHNA MATH No.113 SWAMI VIVEKANADA ROAD, ULSOOR BANGALORE -560 008 Phone: 080 - 25578900 / 25367878 / 9902244822 / 9902019552 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ramakrishnamath.in BOOKS CATALOG KANNADA BOOKS Page no. 1 to 13 ENGLISH BOOKS Page No.14 to 38 TAMIL BOOKS Page No.39 to 47 TELUGU BOOKS Page No.48 to 54 SANSKRIT BOOKS Page No.55 and 56 HINDI BOOKS Page No.56 to 59 BENGALI BOOKS Page No.60 to 68 SUBSIDISED SET BOOKS Page No.69 MISCELLANEOUS BOOKS Page No. 70 and 71 ARTICLES(PHOTOS/CD/DVD/MP3) Page No.72 to 80 KANNADA BOOKS Book Price Code Book Name Rs. 002-6-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 2 KAN 90 003-4-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 3 KAN 120 05951-00 NANNA BHARATA - TEERTHAKSHETRA 15 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 12 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 10 -24 MINCHINA THEARU KAN 120 349.0-00 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 80 349.0-10 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 100 349.0-12 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 120 -43 BHAKTANA LAKSHANA 20 627-4 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALU (KAN) 100 627-4-89 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALA- KAN 100 639-A-00 LALITASAHNAMA (KAN) MYS 16 639A-01 LALTASAHASRANAMA (BOLD KANNADA) 25 639-B SRI LALITA SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN 25 642-A-00 VISHNU SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN BIG 25 648-7 LEADERSHIP FORMULAS (KAN) 100 649-5 EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE (KAN) 100 663-0-08 VIDYARTHI VIJAYA - KAN 100 715-A-00 MAKKALIGAGI SACHITRA SET 250 825-A-00 BADHUKUVA DHARI (KAN) 50 840-2-40 MAKKALA SRI KRISHNA - 2 (KAN) 40 B1039-00 SHIKSHANA RAMABANA 6 B4012-00 SHANDILYA BHAKTI SUTRAS 75 B4015-03 PHIL. -

VII. the Swami Swahananda Era (1976-2012)

Ramakrishna-Vedanta in Southern California: From Swami Vivekananda to the Present VII. The Swami Swahananda Era (1976-2012) 1. Swami Swahananda’s Background 2. Swami Swahananda’s Major Objectives 3. Swami Swahananda at the Vedanta Society of Southern California 4. The Assistant Swamis 5. Functional Departments of the Vedanta Society 6. Charitable Organizations 7. Santa Barbara Temple and Convent 8. Ramakrishna Monastery, Trabuco Canyon 9. Vivekananda House, South Pasadena (1955-2012) 1. Swami Swahananda’s Background* fter Swami Prabhavananda passed away on July 4, 1976, Swami Chetanananda was assigned the position of head of the A Vedanta Society of Southern California (VSSC). Swamis Vireswarananda and Bhuteshananda, President and Vice- President of the Ramakrishna Order, urged Swami Swahananda to take over the VSSC. They realized that a man with his talents and capabilities should be in charge of a large center. Swahananda agreed to leave the quiet life of Berkeley for the more challenging work in the Southland. Having previously been in charge of the large New Delhi Center in the capital of India, he was up to the task and assumed leadership of the VSSC on December 15, 1976. He was enthusiastically welcomed, and soon became well established in the life of the Society. Swami Swahananda was born on June 29, 1921 in Habiganj, Sylhet in Bengal (now in Bangladesh). His father had been a government official and an initiated disciple of Holy Mother. He had wanted to renounce the world and become a monk, but Holy Mother reportedly had told him, “No, my child, but from your family two shall come.” (As well as Swahananda, a nephew also later joined the Ramakrishna Order). -

Balancing Inner and Outer

Editorial Balancing Inner and Outer As the Holy Mother Sesquicentennial Year nears its conclusion, this is perhaps a good time to take stock of what we have learned from Holy Mother’s life and teachings. As spiritual aspirants, we gain a great deal of inspiration for our interior life from her teachings on devotion, work, knowledge, self-effort and self-surrender. From her life, we see how a person living in domestic circumstances can be pure and non-attached as well as loving and concerned. She played her part faultlessly, showing how the highest ideals can be made practical in the workaday world. In some ways her workaday world was a very different place from ours. She did not face the stress of the modern workplace or such a dizzying pace of technological change. But Holy Mother’s world did include terrorism, including state terror, political upheaval, and social stress. Great teachers do not always give us specific answers to specific external challenges. Rather, they give us examples and principles that help us to make the right decisions as we respond to our own particular challenges. We have to engage in our own struggle in our own circumstances. One thing is clear: Holy Mother never attempted to escape or run away from difficulties. Think of her life in the cramped, stuffy Nahabat, without toilet facilities, with fish for her husband’s delicate stomach splashing water all night from a pot hung from the ceiling. Think of her difficulties in Kamarpukur after the Master’s passing, with hardly enough to eat or wear and the constant criticism of her neighbors.