P. 1 Prop. 12.9 CONSIDERATION of PROPOSALS FOR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Miombo Ecoregion Vision Report

MIOMBO ECOREGION VISION REPORT Jonathan Timberlake & Emmanuel Chidumayo December 2001 (published 2011) Occasional Publications in Biodiversity No. 20 WWF - SARPO MIOMBO ECOREGION VISION REPORT 2001 (revised August 2011) by Jonathan Timberlake & Emmanuel Chidumayo Occasional Publications in Biodiversity No. 20 Biodiversity Foundation for Africa P.O. Box FM730, Famona, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe PREFACE The Miombo Ecoregion Vision Report was commissioned in 2001 by the Southern Africa Regional Programme Office of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF SARPO). It represented the culmination of an ecoregion reconnaissance process led by Bruce Byers (see Byers 2001a, 2001b), followed by an ecoregion-scale mapping process of taxa and areas of interest or importance for various ecological and bio-physical parameters. The report was then used as a basis for more detailed discussions during a series of national workshops held across the region in the early part of 2002. The main purpose of the reconnaissance and visioning process was to initially outline the bio-physical extent and properties of the so-called Miombo Ecoregion (in practice, a collection of smaller previously described ecoregions), to identify the main areas of potential conservation interest and to identify appropriate activities and areas for conservation action. The outline and some features of the Miombo Ecoregion (later termed the Miombo– Mopane Ecoregion by Conservation International, or the Miombo–Mopane Woodlands and Grasslands) are often mentioned (e.g. Burgess et al. 2004). However, apart from two booklets (WWF SARPO 2001, 2003), few details or justifications are publically available, although a modified outline can be found in Frost, Timberlake & Chidumayo (2002). Over the years numerous requests have been made to use and refer to the original document and maps, which had only very restricted distribution. -

Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and Its Islands Conservation, Management and Sustainable Use

Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and its Islands Conservation, Management and Sustainable Use Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 6 IUCN - The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biologi- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna cal diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- of fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their vation of species or biological diversity. conservation, and for the management of other species of conservation con- cern. Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: sub-species and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintaining biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of bio- vulnerable species. logical diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conservation Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitoring 1. To participate in the further development, promotion and implementation the status of species and populations of conservation concern. of the World Conservation Strategy; to advise on the development of IUCN's Conservation Programme; to support the implementation of the • development and review of conservation action plans and priorities Programme' and to assist in the development, screening, and monitoring for species and their populations. -

The Miombo Ecoregion

The Dynamic of the Conservation Estate (DyCe) Summary Report: The Miombo Ecoregion Prepared by UNEP-WCMC and the University of Edinburgh for the Luc Hoffmann Institute Authors: Vansteelant, N., Lewis, E., Eassom, A., Shannon-Farpón, Y., Ryan C.M, Pritchard R., McNicol I., Lehmann C., Fisher J. and Burgess, N. Contents Summary ....................................................................................................................................2 The Luc Hoffmann Institute and the Dynamics of the Conservation Estate project .................3 The Miombo ecoregion ..............................................................................................................3 The Social-Ecological System ...................................................................................................6 The Social System......................................................................................................................7 The Ecological System ..............................................................................................................9 Forest Cover .............................................................................................................................12 Vegetation types.......................................................................................................................13 Biodiversity values...................................................................................................................15 Challenges for conservation .....................................................................................................16 -

List of National Parks of Zambia

Sl. No Name Notes 1 Blue Lagoon National Park A small park in the north of the Kafue Flats west of Lusaka, known chiefly for bird life; one lodge 2 Isangano National Park East of the Bangweulu Swamps, no facilities, little wildlife 3 Kafue National Park World-famous for its animals, one of the world's largest national parks, several lodges 4 Kasanka National Park Privately operated, south of the Bangweulu Swamps, one lodge 5 Lavushi Manda National Park South-east of the Bangweulu Swamps, no facilities, little wildlife 6 Liuwa Plain National Park In the remote far west, no facilities but some large herds of animals 7 Lochinvar National Park A small park south of the Kafue Flats world-famous for bird life and herds of lechwe, one lodge 8 Lower Zambezi National Park East of Lusaka, offers good wildlife viewing on the Zambezi River; one lodge 9 Luambe National Park A small park, close to South Luangwa National Park, recovering after previous neglect, one new lodge 10 Lukusuzi National Park East of Luambe, undeveloped but with potential 11 Lusaka National Park Opened in 2015, a small park on the south-east side of the capital city Lusaka 12 Lusenga Plain National Park East of Lake Mweru, no facilities, no easy access, little wildlife The small park for Victoria Falls on the edge of the city of Livingstone (where accommodation is available), 13 Mosi-oa-Tunya National Park (Victoria Falls National Park) includes a small 'safari park' 14 Mweru Wantipa National Park No facilities, neglected, little wildlife but has potential for redevelopment 15 -

Collaborative Management Models for Conservation Areas In

COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT MODELS FOR CONSERVATION AREAS IN MOZAMBIQUE Regional Best Practices, Current Models in Mozambique and a Framework for Enhancing Partnerships to Protect Biodiversity Assets and Promote Development Supporting the Policy Environment for Economic Development (SPEED+) MAY 2018 DISCLAIMER This document was produced by the USAID SPEED+ Project under Contract AID-656-TO-16-00005 at the request of the United States Agency for International Development Mozambique Mission. The document is made possible by the support of the American people through USAID. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the author or authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States government. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the collaboration of ANAC, Biofund, SPEED+, and Nathan Associates Inc., as well as all interviewees and respondents who graciously offered their time, insights, and recommendations. We are especially grateful to ANAC (Bartolomeu Soto, Felismina Langa, Agostinho Nazare, Raimundo Matusse, and all others who contributed their time), Biofund (including Luis Bernardo Honwana, Sean Nazerali, and Alexandra Jorge), SPEED+ (including Sergio Chitara, Ashok Menon, Afonso Madope, Vera Julien), and USAID (in particular, Amanda Fong, Danielle Tedesco, Olivia Gilmore), for their support and the three park wardens and their staff who hosted us during our site visits (Baldeu Chande, Cornelio Miguel, and Mateus Mutemba), for their support and insights in developing the work presented in this report. -

Resource, Protection and Tourism of Kafue National Park, Zambia

PARKS VOL 24.1 MAY 2018 ‘THE GIANT SLEEPS AGAIN?’ ‐ RESOURCE, PROTECTION AND TOURISM OF KAFUE NATIONAL PARK, ZAMBIA Francis X. Mkanda1*, Simon Munthali 2, James Milanzi3, Clive Chifunte4, Chaka Kaumba4, Neal Muswema4, Anety Milimo4 and Ausn Mwakifwamba4 *Corresponding author: [email protected] 1 Mzuzu, Malawi 2 Lilongwe, Malawi 3 African Parks, Johannesburg, Republic of South Africa 4 Department of Naonal Parks and Wildlife, Lusaka, Zambia ABSTRACT The phasing out of the Kafue Programme that aimed to secure critical habitats and species in the Kafue National Park and adjacent Game Management Areas was greeted with mixed reactions. Some stakeholders, particularly tour operators, were despondent; they postulated that the park would revert to the previous state of neglect. Other stakeholders, however, contended that the programme had achieved its purpose. Moreover, such despondency merely risked discouraging potential investors in tourism, the main source of revenue for the park. This study attempts to verify if the despondency was justified. It examines the resource, resource-protection effectiveness and tourism during and after the programme. The results are varied. While populations of ‘key’ wildlife species continued to grow, and numbers of tourists and the associated revenue had increased four years after the programme, illegal activity also increased to the level of the pre-programme period. Therefore, to a certain extent the concern was justified, the giant sleeps again and its potential remains untapped. It is essential for the Department of National Parks and Wildlife to take measures to curb the poaching of all species affected. Key words: challenges, concern, resource, resource protection, tourism, revenue INTRODUCTION great photo opportunities and trips to hot springs. -

Zambian Game Management Areas

ZAMBIAN GAME MANAGEMENT AREAS The reasons why they are not functioning as ecologically or economically productive buffer zones and what needs to change for them to fulfil that role Lindsey, P., Nyirenda, V., Barnes, J., Becker, M., Tambling, C., Taylor, A., Watson, F. Photo: C. Masterson A study commissioned and funded by the Wildlife Producers Association of Zambia Contents Executive summary ................................................................................................................................. 4 Potential benefits associated with CWCs ............................................................................................... 8 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 10 Methods ................................................................................................................................................ 12 Literature survey ............................................................................................................................... 12 Stakeholder survey ........................................................................................................................... 12 Estimating current earnings from Game Management Areas .......................................................... 13 Estimating rates of human population growth rate and encroachment in GMAs ........................... 13 Estimating mammalian biomass in GMAs, national parks and extensive -

(1997). the African Wild Dog: Status Survey and Conservation

Donors to the SCC Conservation Communications Fund and The African Wild Dog Action Plan The IUCN/Species Survival Commission is committed to communicate important species conservation information to natural resource managers, decision-makers and others whose actions affect the conservation of biodiversity. The SSC’s Action Plans, Occasional Papers, news magazine (Species), Membership Directory and other publications are supported by a wide variety of generous donors including: The Sultanate of Oman established the Peter Scott IUCN/SSC Action Plan Fund in 1990. The Fund supports Action Plan development and implementation; to date, more than 80 grants have been made from the Fund to Specialist Groups. As a result, the Action Plan Programme has progressed at an accelerated level and the network has grown and matured significantly. The SSC is grateful to the Sultanate of Oman for its confidence in and support for species conservation worldwide. The Chicago Zoological Society (CSZ) provides significant in-kind and cash support to the SSC, including grants for special projects, editorial and design services, staff secondments, and related support services. The mission of CSZ is to help people develop a sustainable and harmonious relationship with nature. The Zoo carries out its mission by informing and inspiring 2,000,OOO annual visitors, serving as a refuge for species threatened with extinction, developing scientific approaches to manage species successfully in zoos and in the wild, and working with other zoos, agencies, and protected areas around the world to conserve habitats and wildlife. The Council of Agriculture (COA), Taiwan has awarded major grants to the SSC’s Wildlife Trade Programme and Conservation Communications Programme. -

Cop14 Prop. 6

CoP14 Prop. 6 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Fourteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties The Hague (Netherlands), 3-15 June 2007 CONSIDERATION OF PROPOSALS FOR AMENDMENT OF APPENDICES I AND II A. Proposal 1. Amendment of the annotation regarding the populations of Loxodonta africana of Botswana, Namibia and South Africa to: a) include the following provision: "No trade in raw or worked ivory shall be permitted for a period of 20 years except for: 1) raw ivory exported as hunting trophies for non-commercial purposes; and 2) ivory exported pursuant to the conditional sale of registered government-owned ivory stocks agreed at the 12th meeting of the Conference of the Parties."; and b) remove the following provision: "6) trade in individually marked and certified ekipas incorporated in finished jewellery for non-commercial purposes for Namibia". 2. Amendment of the annotation regarding the population of Loxodonta africana of Zimbabwe to read: "For the exclusive purpose of allowing: 1) export of live animals to appropriate and acceptable destinations; 2) export of hides; and 3) export of leather goods for non-commercial purposes. All other specimens shall be deemed to be specimens of species included in Appendix I and the trade in them shall be regulated accordingly. No trade in raw or worked ivory shall be permitted for a period of 20 years. To ensure that where a) destinations for live animals are to be appropriate and acceptable and/or b) the purpose of the import -

Cop18 Prop. 10

Original language: English CoP18 Prop. 10 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Eighteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Colombo (Sri Lanka), 23 May – 3 June 2019 CONSIDERATION OF PROPOSALS FOR AMENDMENT OF APPENDICES I AND II A. Proposal Zambia proposes that the population of African elephant (Loxodonta africana) of Zambia be downlisted from Appendix I to Appendix II subject to 1. Trade in registered raw ivory (tusks and pieces) for commercial purposes only to CITES approved trading partners who will not re-export. 2. Trade in hunting trophies for non-commercial purposes; 3. Trade in hides and leather goods. 4. All other specimens shall be deemed to be specimens of species in Appendix I and the trade in them shall be regulated accordingly B. Proponent Zambia*: C. Supporting statement 1. Taxonomy 1.1 Class: Mammalia 1.2 Order: Proboscidea 1.3 Family: Elephantidae 1.4 Genus, species or subspecies, including author and year: Loxodonta africana africana 1.5 Scientific synonyms: None 1.6 Common names: English: African elephant French: Elephant d’Afrique Spanish: Elefante africano 1.7 Code numbers: CITES A115.001.002.001 2. Overview This proposal is intended to advance sustainable conservation practices for the African elephant population in the Republic of Zambia. The Zambian population of the African elephant no longer meets the biological * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

2019 ZCP Annual Report

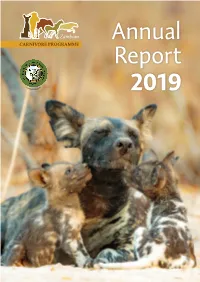

Annual Report “C ” ON IFE SERVE WILDL 2019 i ANNA KUSLER A cheetah cub eyes its surroundings in the Greater Liuwa Ecosystem of Western Zambia. A transboundary ecosystem with connectivity to Angola, Liuwa hosts Zambia’s second-largest cheetah population. Table of Contents The Year in Review . 1 Our Approach . .2 . Where We work . 4 . Field Reports . 5 Luangwa Valley . 5 . Greater Kafue . 10 . Greater Liuwa . 15 . Greater Kabompo and Greater Nsumbu . .21 . Conservation Action . .23 . Empowerment . .30 . The Science of Conservation . 38. 2019 Supporters . .41 . Cover: Pups from the Luangwa’s Baobab Pack nuzzle their mother. One of the largest packs in the study, Baobab was the Zambian Carnivore Programme direct result of collaborative anti-snaring work by ZCP, DNPW PO Box 80, Mfuwe, Eastern Province, Zambia and Conservation South Luangwa. Read their story on page 6. www.zambiacarnivores.org Photo by Edward Selfe. The Year in Review We concluded another momentous year in 2019, patrols by DNPW and partners to reduce snaring working with the Department of National Parks by-catch and prey depletion, we jointly developed and Wildlife (DNPW) and an array of partners human-carnivore conflict mitigation to conserve large carnivores and ecosystems programmes in the Luangwa and Liuwa, we across Zambia . Our work extended across 7 developed genetic tools for combatting national parks and seven Game Management trafficking of big cats and for evaluating connec- Areas, as we logged over 2,700 person days in the tivity between ecosystems; and we continued to field, and intensively monitored nearly 1,000 evaluate human encroachment and provide individual carnivores . -

Protected Area System Master Plan

FOREWORD The Protected Areas (PAs) management in Zambia has suffered a number of setbacks for various reasons. These largely include limited financial and human resources, limited institutional capacity and inadequate sectoral laws. However, even the limited ranges of PA categories have had their own telling effects. In an effort to address some of the highlighted shortcomings, the Government of the Republic of Zambia (GRZ) commenced the Reclassification and Effective Management of the National Protected Areas System (REMNPAS) Project in 2006. The Project is examining and will put in place appropriate policy, regulatory and governance frameworks in order to provide new tools for Public-Private-Community and Civil Society management partnerships. The Project also aims at enhancing and strengthening the existing institutional capacities for improved Protected Areas representation, monitoring and evaluation including business and investment planning. The Government of the Republic of Zambia is piloting the initiative of devolving management responsibility to effective partnerships involving local communities. This is achieved by attracting private finance to help in the protection of PAs in a long term commitment. To a greater extent this assures PAs of sustainable finance and that way the Public Private Community Partnership approach secures promise for their future. Ironically, private finance could not be secured to support PAs in their current form. It therefore means that for private sector to participate with confidence, and make investment, a number of issues ought to be addressed starting with the review of the national legislation and in the process expand on the categories of PAs. It is clear that there are limited PA categories in Zambia, and these are not attractive enough to inspire private sector investment.