Forecast Evaluation Report Evaluation Forecast Onlinepublishedonline by TSO (The Stationery Office) and Available From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Technologies and Their Role in Australia's Security, Cultural, Democratic, Social A

At last – a narrative for Australia For many years we have debated where we are heading as a nation. We have been fortunate to have had a relatively prosperous and happy existence and tend to think that this is a direct result of our abundance of minerals and our agricultural production. While our prosperity has been dependent on resources it has only worked because we have been world class in our production techniques and the technology and scientific research that sits behind them. Make no mistake, Australia is not alone in having huge quantities of iron ore: Brazil has just as much and it is generally higher grade. We compete against the world for our economic success. But what of the future? We seem to have no clear narrative other than that as a small nation we must compete against the rest of the world. And the future can be frightening when one notes the way technology is utterly changing the landscape. Some of the wilder predictions suggest that by 2030, 80% of all jobs will be in firms or institutions that don’t exist now. Aviva Rutkin writing in the MIT Technology Journal1 on the jobs of the future suggested that around half of all currently existing jobs in the USA would be automated by 2030. The good news of course is that while technology is destroying jobs it is also creating jobs. Our narrative then is clear: we must pursue innovation through technology as the main contributor to our future prosperity and happiness. The new jobs generated will allow us to compete with the world. -

Economic Review of July 2016

Suite 28, 30 Churchill Square, Kings Hill Kent, ME19 4YU Tel: 01732 525905 Fax: 01732 525906 Email: [email protected] www.lsfp.co.uk ECONOMIC REVIEW OF JULY 2016 AHEAD OF BREXIT VOTE, BANK OF ENGLAND HOLDS INTEREST UK’S ECONOMY THRIVES RATE AT 0.5% The UK’s economy, in the three months ending June this year, grew Despite most market watchers, and the financial markets generally, by a better than expected 0.6% (2.2% on a yearly basis), according to pencilling in an 80% chance of the Bank of England reducing its the latest data released from the Office for National Statistics (ONS). benchmark interest rate at July’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) from its current historically low 0.5%, the members of the MPC voted 8-1 to leave the rate unchanged, with Jan Vlieghe being the one member voting for a rate reduction. However, it is believed that most of the committee think that some action may need to be taken at the August meeting. As the subsequent press release stated: “The precise size and nature of any stimulatory measures will be determined during the August forecast and Inflation Report round.” The economic dilemma the MPC members face is the contrary effects of a reduction in economic activity, or growth therein, after the Brexit vote, which may have a recessionary effect and the possibility of a rate reduction inducing inflationary pressure on the economy as a result of any interest rate cut putting further downward pressure on Sterling. Better than expected data from ONS The Bank added that it saw “significant weakening” in housing market activity with interest from UK homebuyers falling to its lowest level seen since the middle of 2008. -

Offi Ce for National Statistics Annual Report and Accounts 2005

Offi ce for National Statistics Annual Report and Accounts 2005/06 www.statistics.gov.uk HC1240 Offi ce for National Statistics Annual Report and Accounts 2005/06 Presented to the House of Commons in pursuance of section 6(4) of the Government Resource and Accounts Act 2000 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 13 July 2006 HC 1240 LONDON: The Stationery Office £20.50 © Crown copyright 2006. Published with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. You may re-use this publication (excluding logos) free of charge in any format for research, private study or internal circulation within an organisation. You must re-use it accurately and not use it in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and you must give the title of the source publication. Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is also available on the Office for National Statistics website: www.statistics.gov.uk/about For any other use of this material please apply for a Click-Use Licence for core material at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/system/online/plogin.asp or by writing to: Office of Public Sector Information Information Policy Team St Clements House 2–16 Colegate Norwich NR3 1BQ Fax: 01603 723000 Email: [email protected] For more information, contact: National Statistics Customer Contact Centre Office for National Statistics Government Buildings Cardiff Road Newport NP10 8XG Tel: 0845 -

List of Journals with Electronic Table of Contents in Economics Section Between January and August 2012: 1) European Business O

Journal Table of Contents (Journal TOC) latest update – August 2012 List of journals with electronic table of contents in Economics section between January and August 2012: 1) European Business Organization Law Review 2) European Economic Review 3) European Journal of Law and Economics 4) European Journal of Political Economy 5) European Review of Economic History 6) Géoeconomie 7) Intereconomics 8) International Economics and Economic Policy 9) International Economics 10) Journal of World Trade 11) Oxford Review of Economic Policy 12) Reflets et Persperctives de la Vie Economique 13) Review of World Economics 14) Revue Internationale de Droit Economique 15) World Bank Economic Review 16) World Bank Research Observer 17) World Competition Law and Economics Review 18) World Economy Back to title list European Business Organization Law Review VOL. 12 2011/4 Contents Articles Irit Mevorach, On the Road to Universalism: A Comparative and Empirical Study of the UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency ............................................................................... 517 Jennifer Payne, Private Equity and Its Regulation in Europe ....................... 559 Andrea Sacco Ginevri, The Rise of Long-Terni Minority Shareholders' Rights in Publicly Held Corporations and Its Effect on Corporate Governance ............................................................................. 587 Carlo Drago, Stefano Manestra & Paolo Santella, Interlocking Directorships and Cross-Shareholdings among Italian Blue Chips 619 Wei Cai, The Mandatory -

The First 50 Years of the Government Economic Service Lecture by Dave

The First 50 years of The Government Economic Service Lecture by Dave Ramsden 27 April 2015 1. [Slide 1] Welcome to King’s. Thanks to the Strand Group at the Policy Institute here at King’s and to Hewlett Packard for hosting this lecture and to all of you for attending.1 2. The Government Economic Service (GES) was created in October 1964. The new Wilson Government, with a majority of four, embarked on a more planned approach to the UK economy.2 The Department of Economic Affairs (DEA) was created with a longer term mandate, with HM Treasury meant to focus more on its Finance Ministry role. 3. [Slide 2] Several of the new Special Advisers were economists, including Robert Neild,3 who re-joined HMT. Alec Cairncross, as Head of the Treasury’s Economic Section the Government’s chief economist, worked to ensure the section stayed under civil service management. It did and Cairncross in his words “ended up with the title Head of the Government Economic Service. Ironically the Economic Service has survived to this day while the Economic Section vanished in the 1980s”.4 4. Ironically, because the fledgling GES, 22 strong of whom 18 were already in the Economic Section, was for Cairncross “at first largely a fantasy”, with little influence over staffing or resources. 5. As we are well into 2015 we can mark another anniversary: 100 years ago in 1915 Keynes started working in the Treasury.5 1 I would like to thank my colleagues Lisa Barrance, Andrew Gurney, Leeanne Johnston, Nayeem Khan, Nick Macpherson, Charlotte McKinley, Jake Nelson, Mario Pisani, James Richardson and Daniel Tomlinson for their help and comments. -

THE TREASURY and the SUPPLY SIDE John Kingman Sagging

THE TREASURY AND THE SUPPLY SIDE John Kingman Sagging productivity is the economic challenge of our age. If we were able to ascend Mount Olympus, or at least go to Basel or Jackson Hole, and eavesdrop on any gathering of the central banking elite, very likely what we would witness is the wringing of hands. The central bank drugs successfully saved the patient in 2008. But they are not bringing the patient back to health. So what we need, everyone says, is concerted supply- side reform. All true. My topic here this evening is specifically institutional – what, if any, is the right role for the Treasury in meeting this challenge? For most of its life, that is to say hundreds of years, really the Treasury’s sole purpose was to manage the public finances. During the twentieth century, macroeconomic management became important as well. More recently – for around 30 years - the Treasury has slowly grown a third limb. It has developed what has proved a sustained interest in microeconomics and the supply-side. I want to home in on this “third mission”. What has really been achieved? And should the Treasury have this third purpose at all? These questions are not uncontested. I don’t want to shock anyone, but there is a view held by some Treasury colleagues in private, that all this supply-side stuff is at best a waste of time – lots of gimmicks – or at worst actively damaging, corrupting of the Treasury’s fundamental responsibility to grip the public finances. Then there is a directly opposite challenge – which holds that actually this supply-side stuff is very important, in fact too important to leave to the Treasury. -

UK Statistics Authority ANNUAL REPORT and ACCOUNTS 2016/17

UK Statistics Authority ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2016/17 HC 29 UK Statistics Authority ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2016/17 Accounts presented to the House of Commons pursuant to section 6(4) of the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 Accounts presented to the House of Lords by Command of Her Majesty Annual Report presented to Parliament pursuant to section 27(2) of the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 Annual Report presented to the Scottish Parliament pursuant to section 27(2) of the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 Annual Report presented to the National Assembly for Wales pursuant to section 27(2) of the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 Annual Report presented to the Northern Ireland Assembly pursuant to section 27(2) of the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 13 July 2017 HC 29 UKSA/2017/01 Note: UK Statistics Authority is referred to as ‘the Statistics Board’ in the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 This is part of a series of departmental publications which, along with the Main Estimates 2016/17 and the document Public Expenditure: Statistical Analyses 2013, present the Government’s outturn for 2016/17 and planned expenditure for 2016/17. © Crown copyright 2017 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. -

List of Journals with Electronic Table of Contents in Economics Section Between January and December 2012

Journal Table of Contents (Journal TOC) latest update – December 2012 List of journals with electronic table of contents in Economics section between January and December 2012: 1) European Business Organization Law Review 2) European Economic Review 3) European Journal of Law and Economics 4) European Journal of Political Economy 5) European Review of Economic History 6) Géoeconomie 7) Intereconomics 8) International Economics and Economic Policy 9) International Economics 10) Journal of World Trade 11) Oxford Review of Economic Policy 12) Reflets et Persperctives de la Vie Economique 13) Review of World Economics 14) Revue Internationale de Droit Economique 15) World Bank Economic Review 16) World Bank Research Observer 17) World Competition Law and Economics Review 18) World Economy Back to title list European Business Organization Law Review VOL. 12 2011/4 Contents Articles Irit Mevorach, On the Road to Universalism: A Comparative and Empirical Study of the UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency ............................................................................... 517 Jennifer Payne, Private Equity and Its Regulation in Europe ....................... 559 Andrea Sacco Ginevri, The Rise of Long-Terni Minority Shareholders' Rights in Publicly Held Corporations and Its Effect on Corporate Governance ............................................................................. 587 Carlo Drago, Stefano Manestra & Paolo Santella, Interlocking Directorships and Cross-Shareholdings among Italian Blue Chips 619 Wei Cai, The Mandatory -

ONS Annual Report and Accounts 2006/07 HC

Offi ce for National Statistics Annual Report and Accounts 2006/2007 Presented to the House of Commons in pursuance of section 6(4) of the Government Resource and Accounts Act 2000 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 17 July 2007 HC 627 The Stationery Office: London £18.00 © Crown Copyright 2007 The text in this document (excluding any Royal Arms and departmental logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Any queries relating to the copyright in this document should be addressed to The Licensing Division, HMSO, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich, NR3 1BQ. Fax: 01603 723000 or e-mail: [email protected] For more information, contact: National Statistics Customer Contact Centre Office for National Statistics Government Buildings Cardiff Road Newport NP10 8XG Tel: 0845 601 3034 Email: [email protected] Minicom: 01633 652747 xli Offi ce for National Statistics | Annual Report and Accounts 2006/2007 Contents Director’s Message 1 I Director’s Report 2 Background 2 ONS aims and objectives 3 ONS management 4 Board structure 5 People 6 Health and safety 7 Progress towards sustainable development 9 Freedom of Information 11 The European Union and international activity 11 II Management Commentary 13 Overview 13 Independence 15 2006/07 review 16 Summary of fi nancial performance 16 Summary of achievements 18 Targets from the 2004 Spending Review 18 Risk management 31 Stakeholder management 31 Looking Forward 34 Annexes Annex A Targets from the 2002 Spending Review 35 Annex B ONS Publishing Plan 36 III Resource Accounts 41 xlii Offi ce for National Statistics | Annual Report and Accounts 2006/2007 Director’s Message Modernisation, effi ciency and relocation – these are the big challenges ONS staff have worked towards this year. -

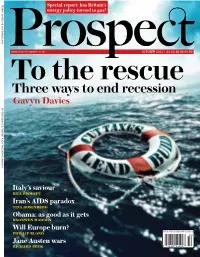

Three Ways to End Recession Gavyn Davies to the Rescue: Three Ways Three Recession End to Rescue: the To

Special report: has Britain’s energy policy turned to gas? issue 199 | october 2012 www.prospect-magazine.co.uk october 2012 | £4.50 $6.99 €6.90 To the rescue Three ways to end recession Gavyn Davies to the rescue: to end recession three ways Italy’s saviour bill emmott Iran’s AIDS paradox tina rosenberg Obama: as good as it gets bronwen maddox Will Europe burn? ISSN 1359-5024 phillip blond A$10.95 NZ$12.50 US$6.99 €6.90 Can$7.99 10 Jane Austen wars richard beck 9 771359 502057 Our fund managers’ most useful tool No. 7: A travel clock Over the past year, we personally interviewed the management of over 3,000 companies worldwide. Murray International Trust Stocks and Shares ISA and Share Plan There’s nothing like being able to judge for yourself. The value of tax benefits depends on individual For us, we won’t add a company to our portfolios without circumstances and the favourable tax treatment first holding a personal interview with its management. for ISAs may not be maintained. Established in 1907, Murray International Trust PLC is If you have any doubts about the suitability of a conventional investment trust that aims to generate any investment for your needs, please consult an income from a large, diversified global portfolio, and independent financial adviser. is available through our ISA or Share Plan. We only 0500 00 40 00 ever invest in companies that our regional investment Request a brochure: teams have personally selected and approved. www.invtrusts.co.uk You can invest in this trust from £100 per month or £1,000 lump sum. -

National Institute of Economic and Social Research

NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL RESEARCH COUNCIL OF MANAGEMENT President Director Lord Burns Martin Weale Appointed November 2003; Appointed October 1995 Chairman of Abbey plc; formerly Economics Fellow, Chairman of Welsh Water; Clare College Chairman (designate) Channel 4 Television Chairman of Council Secretary Professor Timothy Besley Gill Clisham Appointed November 2008; Appointed January 2001 Kuwait Professor of Economics and Political Science, London School of Economics; Director of STICERD; Member, Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee NICHOLAS BARBER PROFESSOR JOHN ERMISCH Chairman, Bolero International Ltd Institute for Social and Economic Research, KATE BARKER University of Essex Member, Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee PROFESSOR JOHN HILLS PROFESSOR CHARLES BEAN Director of CASE, Professor of Social Policy, Deputy Governor, Bank of England London School of Economics PROFESSOR TIMOTHY BESLEY PROFESSOR HEATHER JOSHI Professor of Economics and Political Science, London Centre for Longitudinal Studies, Institute of Education, School of Economics; Director of STICERD; Member, University of London Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee HANS LIESNER COLETTE BOWE Former Deputy Chairman, Monopolies and Mergers Ofcom Commission PROFESSOR WILLEM H BUITER DR JOHN LLEWELLYN Professor of European Political Economy, Llewellyn Consulting London School of Economics SIR NICHOLAS MONCK LORD BURNS Former Permanent Secretary, Employment Department Chairman, Abbey plc, Welsh Water, and DR SUSHIL WADHWANI Chairman (designate), Channel 4 Television Wadhwani Asset Management BRONWYN CURTIS MARTIN WEALE Head of Global Research, HSBC Bank plc Institute Director The Institute is an independent non-profit-making body, incorported under the Companies Acts, limited by guarantee and registered under the Charities Act 1960 (Registered Charity Number 306083). WHERE TO FIND US The National Institute welcomes enquiries on all aspects of its work, and suggestions for collaboration with universities, business or government. -

UK Statistics Authority

UK Statistics Authority ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2013/14 Annual Report 2013-14_FINAL.indd 1 10/07/2014 13:10 Annual Report 2013-14_FINAL.indd 2 10/07/2014 13:10 UK Statistics Authority ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2013/14 Accounts presented to the House of Commons pursuant to section 6(4) of the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 Accounts presented to the House of Lords by command of Her Majesty Annual Report presented to Parliament pursuant to section 27(2) of the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 Annual Report presented to the Scottish Parliament pursuant to section 27(2) of the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 Annual Report presented to the National Assembly for Wales pursuant to section 27(2) of the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 Annual Report presented to the Northern Ireland Assembly pursuant to section 27(2) of the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 10 July 2014 HC 34 UKSA/2014/01 Note: UK Statistics Authority referred to as ‘the Statistics Board’ in the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 Annual Report 2013-14_FINAL.indd 1 10/07/2014 13:10 This is part of a series of departmental publications which, along with the Main Estimates 2014/15 and the document Public Expenditure: Statistical Analyses 2013, present the Government’s outturn for 2013/14 and planned expenditure for 2014/15. © Crown copyright 2014 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v.2.