1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Foreign Affairs Series AMBASSADOR WILLIAM T. PRYCE Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: September 22, 1997 Copyright 2007 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in California raised in Pennsylvania Wesleyan University and the Fletcher School of Tufts University US Navy Department of Commerce Entered the Foreign Service in 1958 State Department* Fuels Division Economic Bureau/Staff Asst. 1958-19.0 Ara0-1srael policy Assistant Secretary Thomas 2ann Frances Wilson State Department 3atin America Bureau 4ARA6 19.0-19.1 Cu0a-Bay of Pigs 2e7ico City 2e7ico* Consular Officer/Staff Aide 19.1-19.8 Protection cases President 9ennedy:s visit River boundary disputes Relations Government 9ennedy assassination State Department* Staff Assistant 4ARA6 19.8-19.5 Dominican Repu0lic intervention Organization of American States 4OAS6 Am0assador Tapley Bennett State Department* FS1 Russian language training 19.5-19.. 2oscow Soviet Union* Pu0lications Procurement Officer 19..-19.8 1 3enin 3i0raries Travel formalities 9GB Baltic nations Brezhnev Am0assador Thompson Environment Pu0lic contacts Soviet intelligentsia Panama City Panama* Political Officer 19.8-1971 Arnulfo Arias Panama Canal Treaty Canal operation Relations US sovereignty questions Noriega Torrijos Guatemala City Guatemala* Political Counselor 1971-1974 Security Government Elections Environment USA1D 2ilitary Political Parties State Department* Soviet E7change Program* 1974-197. Educational -

Table of Contents

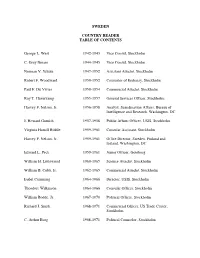

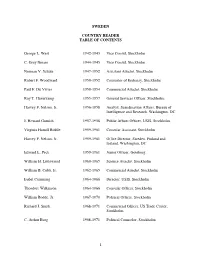

SWEDEN COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS George L. West 1942-1943 Vice Consul, Stockholm C. Gray Bream 1944-1945 Vice Consul, Stockholm Norman V. Schute 1947-1952 Assistant Attaché, Stockholm Robert F. Woodward 1950-1952 Counselor of Embassy, Stockholm Paul F. Du Vivier 1950-1954 Commercial Attaché, Stockholm Roy T. Haverkamp 1955-1957 General Services Officer, Stockholm Harvey F. Nelson, Jr. 1956-1958 Analyst, Scandinavian Affairs, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Washington, DC J. Howard Garnish 1957-1958 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Stockholm Virginia Hamill Biddle 1959-1961 Consular Assistant, Stockholm Harvey F. Nelson, Jr. 1959-1961 Office Director, Sweden, Finland and Iceland, Washington, DC Edward L. Peck 1959-1961 Junior Officer, Goteborg William H. Littlewood 1960-1965 Science Attaché, Stockholm William B. Cobb, Jr. 1962-1965 Commercial Attaché, Stockholm Isabel Cumming 1964-1966 Director, USIS, Stockholm Theodore Wilkinson 1964-1966 Consular Officer, Stockholm William Bodde, Jr. 1967-1970 Political Officer, Stockholm Richard J. Smith 1968-1971 Commercial Officer, US Trade Center, Stockholm C. Arthur Borg 1968-1971 Political Counselor, Stockholm Haven N. Webb 1969-1971 Analyst, Western Europe, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Washington, DC Patrick E. Nieburg 1969-1972 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Stockholm Gerald Michael Bache 1969-1973 Economic Officer, Stockholm Eric Fleisher 1969-1974 Desk Officer, Scandinavian Countries, USIA, Washington, DC William Bodde, Jr. 1970-1972 Desk Officer, Sweden, Washington, DC Arthur Joseph Olsen 1971-1974 Political Counselor, Stockholm John P. Owens 1972-1974 Desk Officer, Sweden, Washington, DC James O’Brien Howard 1972-1977 Agricultural Officer, US Department of Agriculture, Stockholm John P. Owens 1974-1976 Political Officer, Stockholm Eric Fleisher 1974-1977 Press Attaché, USIS, Stockholm David S. -

Russia's Strategy for Influence Through Public Diplomacy

Journal of Strategic Studies ISSN: 0140-2390 (Print) 1743-937X (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fjss20 Russia’s strategy for influence through public diplomacy and active measures: the Swedish case Martin Kragh & Sebastian Åsberg To cite this article: Martin Kragh & Sebastian Åsberg (2017): Russia’s strategy for influence through public diplomacy and active measures: the Swedish case, Journal of Strategic Studies, DOI: 10.1080/01402390.2016.1273830 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2016.1273830 Published online: 05 Jan 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 32914 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fjss20 Download by: [Anna Lindh-biblioteket] Date: 21 April 2017, At: 02:48 THE JOURNAL OF STRATEGIC STUDIES, 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2016.1273830 Russia’s strategy for influence through public diplomacy and active measures: the Swedish case Martin Kragha,b and Sebastian Åsbergc aHead of Russia and Eurasia Programme, Swedish Institute of International Affairs, Stockholm; bUppsala Centre for Russian and Eurasian Studies, Uppsala University, Sweden; cRussia and Eurasia Studies, Swedish Institute of International Affairs ABSTRACT Russia, as many contemporary states, takes public diplomacy seriously. Since the inception of its English language TV network Russia Today in 2005 (now ‘RT’), the Russian government has broadened its operations to include Sputnik news websites in several languages and social media activities. Moscow, however, has also been accused of engaging in covert influence activities – behaviour historically referred to as ‘active measures’ in the Soviet KGB lexicon on political warfare. -

Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko and Sweden by Sven Hirdman

KUNGL KRIGSVETENSKAPSAKADEMIENS HANDLINGAR OCH TIDSKRIFT DISKUSSION & DEBATT Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko and Sweden by Sven Hirdman ormer Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei The relations between Sweden and the FGromyko, whose 100th birthday is Soviet Union got on to a new footing commemorated this year, had several con- when, in April 1956, Prime Minister Tage tacts with Sweden from 1948 until 1984. Erlander and his coalition partner Minister To Swedish diplomats he was a very well- for the Interior, Gunnar Hedlund, paid known figure and, I would say, a respected an official visit to the Soviet Union – the statesman. I met him on a few occasions, first ever by a Swedish Prime Minister. As as described below. First Deputy Foreign Minister, Gromyko Andrei Gromyko’s first contact with should have participated in this event. Sweden was in 1948. He was then the So- Substantial talks took place with the Soviet viet Representative to the United Nations. Government, led by Nikita Khrushchev Suddenly, he had to return to Moscow for and Nikolai Bulganin, on international is- family reasons and boarded the Swedish sues and on Swedish – Russian relations, Atlantic liner Gripsholm, being the fastest including the well-known Raoul Wallen- connection. Had he, as originally planned, berg case. A year later, in February 1957, taken the Soviet ship Pobeda, he would it was Gromyko who handed the Swedish have suffered disaster, as the Pobeda Ambassador in Moscow, Mr Rolf Sohl- caught fire in the Black Sea and many pe- man, a note saying that Wallenberg had ople died. Gromyko describes the incident died in the Lyubyanka prison in July 1947. -

Rhode Island History Summer / Fall 2016 Volume 74, Number 2

RHODE ISLAND HISTORY SUMMER / FALL 2016 VOLUME 74, NUMBER 2 RHODE ISLAND HISTORY SUMMER / FALL 2016 VOLUME 74, NUMBER 2 IN THIS ISSUE 48 An Interview with Anthony Calandrelli Fashioning Rhode Island Michelle Johnson 52 Making Brown University’s “New Curriculum” in 1969: The Importance of Context and Contingency Luther Spoehr 72 Slaver Captain and Son of Newport: Philip Morse Topham and Jeersonian Justice Craig A. Landy Published by Publications Committee Sta The Rhode Island Historical Society Theodore Smalletz, chair (on leave) Elizabeth C. Stevens, editor 110 Benevolent Street Luther W. Spoehr, interim chair Silvia Rees, publications assistant Providence, Rhode Island 02906–3152 Robert W. Hayman The Rhode Island Historical Society James P. Loring, chair Jane Lancaster assumes no responsibility for the Luther W. Spoehr, Ph.D., vice chair J. Stanley Lemons opinions of contributors. Gayle A. Corrigan, treasurer Craig Marin Alexandra Pezzello, Esq., secretary Seth Rockman C. Morgan Grefe, director Marie Schwartz © The Rhode Island Historical Society Evelyn Sterne RHODE ISLAND HISTORY (ISSN 0035–4619) William McKenzie Woodward On the cover: Ira Magaziner in the midst of discussion outside University Hall. Courtesy: Brown University Archives. Fashioning Rhode Island An Interview with Anthony Calandrelli by Michelle Johnson During 2016, the Rhode Island Historical Society rings, but they made rings using die struck, has been developing programming for the theme, which means you had to make a hub and a die “Fashioning Rhode Island.” We have been exploring and have a big press. They would put a sheet of Rhode Island’s rich history of industry and inge- metal in between it, and it would come down nuity, including jewelry-making in Providence and and strike it. -

Table of Contents

SWEDEN COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS George L. West 1942-1943 Vice Consul, Stockholm C. Gray Bream 1944-1945 Vice Consul, Stockholm Norman V. Schute 1947-1952 Assistant Attaché, Stockholm Robert F. Woodward 1950-1952 Counselor of Embassy, Stockholm Paul F. Du Vivier 1950-1954 Commercial Attaché, Stockholm Roy T. Haverkamp 1955-1957 General Services Officer, Stockholm Harvey F. Nelson, Jr. 1956-1958 Analyst, Scandinavian Affairs, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Washington, DC J. Howard Garnish 1957-1958 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Stockholm Virginia Hamill Biddle 1959-1961 Consular Assistant, Stockholm Harvey F. Nelson, Jr. 1959-1961 Office Director, Sweden, Finland and Iceland, Washington, DC Edward L. Peck 1959-1961 Junior Officer, Goteborg William H. Littlewood 1960-1965 Science Attaché, Stockholm William B. Cobb, Jr. 1962-1965 Commercial Attaché, Stockholm Isabel Cumming 1964-1966 Director, USIS, Stockholm Theodore Wilkinson 1964-1966 Consular Officer, Stockholm William Bodde, Jr. 1967-1970 Political Officer, Stockholm Richard J. Smith 1968-1971 Commercial Officer, US Trade Center, Stockholm C. Arthur Borg 1968-1971 Political Counselor, Stockholm 1 Haven N. Webb 1969-1971 Analyst, Western Europe, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Washington, DC Patrick E. Nieburg 1969-1972 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Stockholm Gerald Michael Bache 1969-1973 Economic Officer, Stockholm Eric Fleisher 1969-1974 Desk Officer, Scandinavian Countries, USIA, Washington, DC William Bodde, Jr. 1970-1972 Desk Officer, Sweden, Washington, DC Arthur Joseph Olsen 1971-1974 Political Counselor, Stockholm John P. Owens 1972-1974 Desk Officer, Sweden, Washington, DC James O’Brien Howard 1972-1977 Agricultural Officer, US Department of Agriculture, Stockholm John P. Owens 1974-1976 Political Officer, Stockholm Eric Fleisher 1974-1977 Press Attaché, USIS, Stockholm David S. -

Math Derived, Math Applied

MATH DERIVED, MATH APPLIED THE ESTABLISHMENT OF BROWN UNIVERSITY’S DIVISION OF APPLIED MATHEMATICS, 1940-1946 Senior Thesis By Clare Kim Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In the Department of History at Brown University Thesis Advisor: Luther Spoehr Submitted 18 April 2011 2 “Is it coincidence that the founding of the École Polytechnique just preceded the beginning of Napoleon’s successful army campaigns? Is it coincidence that fundamental research in ship construction was assiduously prosecuted in Britain during the period just before 1900, when the maritime commerce of that great nation held an assured position of world leadership? Is it coincidence that over the last quarter century airplane research at Göttingen and other German centers was heavily subsidized and vigorously pursued and that in this war German aviation has come spectacularly to the forefront? Is there a lesson to be learned here in America from the consideration of such concurrence?” —R.G.D. Richardson, April 1943 American Journal of Physics 3 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 1 From Dysfunction to Unity, 1940-1941 CHAPTER 2 Meeting the Challenge, 1941-1942 CHAPTER 3 Expanding Horizons, 1942-1943 CHAPTER 4 Applied Mathematics Established, 1944-1946 CONCLUSION BIBLIOGRAPHY 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Most importantly, I have benefited enormously under the guidance of Professors Luther Spoehr and Joan Richards. Their humor, wisdom, encouragement, and thoughtful comments guided me through the thesis process to the very end. It is also a privilege to be able to thank the wide variety of scholars and individuals who took the time to discuss my research. -

Dag Hammarskjöld Remembered

It is now fi fty years since Dag Hammarskjöld left the world and the United Nations behind. Yet, with every passing year since his death, his stature grows and his worth along with his contribution becomes more apparent and meaningful. Dag Hammarskjöld Remembered | When Hammarskjöld was at its helm the United Nations was still a relatively young organization, fi nding its way in a post-war world that had entered a new phase, the cold war, for which there was no roadmap. He was a surprise choice as Secretary-General, a so-called “safe” choice as there was little expectation that this former Swedish civil servant would be more than a competent caretaker. Few imagined that Dag Hammarskjöld would embrace his destiny with such passion and independence and even fewer could have foreseen that he would give his life in service to his passion. But as Hammarskjöld himself stated: “Destiny is something not to be desired and not to be avoided – a mystery not con- A Collection Memories of Personal trary to reason, for it implies that the world, and the course of human history, have meaning.” Th at statement sums up his world view. Th is is a volume of memoirs written by people who knew Hammarskjöld. We hope that these memories succeed in imparting to those who never knew or worked with Dag Hammarskjöld the intrinsic fl avour of this unusual, highly intelligent, highly complex individual who believed deeply in the ability of people, especially their ability to aff ect the world in which they live. He once refl ected: “Everything will be all right – you know when? When people, just people, stop thinking of the United Nations as a weird Picasso abstraction and see it as a drawing they made themselves.” Today that advice rings as true as ever. -

Dr. Henry Wriston To

Te~ple Beth El 10 70 Orchard /\ve , Providence , R. I . Rhode Island's Only Anglo-Jewish Greatest Newspaper Independent In Weekly The Jewish Herald Rhode lslond VOL. XXXX, No. 28 FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 9, 1955 PROVIDENCE. R. I . S IXTEEN PAGES 10 CENTS THE COPY -------- --- ----------------- Jluz_ 'Yw,v,a, oJicJ:uM_ Dr. Henry Wriston to Get 1 An AJP Round U p Of World New·s-------""' ISRAEL been accused of collaborating with It is now fully known in Israel the Hungarian Nazis at the ex B'nai B'rith Service A ward that most of the n e w Egyptian pe nsc of thousands of J e wis h a rms wer e supplied by Britain. lives Pre mier Moshe S harrett despite the Tripartite Declaration has call ed for a "determined a nd Reception·, Dinner of May 1950 in which the U_ S .. sustained effort to accelerate the Levy and Fain to Direct GJC Britain and France undertook to pace of immi_g"ration" of J ews from supply arms only for the main- North Africa A Jewish Ag tcnan ce of internal security and e ncy Committee has recomm e nded Trades and Industry Groups On September 21 legitimate sctr-dcfcn se So bringing 40.000 North African far. Britain has s upplied Egypt Jews to I srael in the coming J ew Rabbi Llyveld with a bout fifty Vampite j ets - is h calendar year. two of which Israel shot down PEOPLE To Make Award last week-and forty Centurian Sr mah Cecil H yman, Is rael ·s tanks It appears th en that new Cons ul Gen eral of New York. -

3 Hotet Från Öst

3 Hotet från öst 3.1 Sovjetunionen och Norden För Sovjetunionen var Norden vid slutet av 1960-talet inte något prioriterat område. Mot bakgrund bl.a. av de spända relationerna till Kina var en förbättring av relationerna till väst, och särskilt fortsatt avspänning gentemot den andra supermakten, de viktigaste prioriteterna för den sovjetiska utrikespolitiken. På den europeiska scenen var det för Moskva av vikt att få principen om status quo efter andra världskriget befäst, och att få till stånd en europeisk säkerhetskonferens för detta ändamål. Vägen dit låg via de stora fördragsverken rörande Tyskland och Centraleuropa, och Norden låg i detta perspektiv vid sidan av. 3.1.1 Allmänt Den ökade militära betydelse som Nordområdena (med Nordområdena menas här norra Norge, Sverige och Finland, och angränsande havsområden i Norska havet och Barents hav), senare under 1970-talet skulle komma att få hade ännu vid slutet av 1960- talet inte börjat göra sig gällande. Norden var ”den glömda flanken”. Moskvas intresse vid denna tid var av allt att döma att bevara Norden som ett lågspänningsområde. Sällan gjorde sovjet- ledningen uttalanden om Norden eller frågor som rörde de nordiska länderna, och i den sovjetiska pressen var ämnet vid denna tid sparsamt förekommande. Det ansågs dock i det sovjetiska utrikesministeriet att en ”aktivisering” av Nato i de nordliga med- lemsländerna Danmark och Norge pågick.1 Genom sin geografiska position var det ofrånkomligt att Norden drogs in i den globala öst-västkonfrontationen, och även om området inte låg i centrum för supermakternas intresse är det i 1 Promemoria 1970-06-10, Skandinaviska avdelningen vid det sovjetiska utrikesministeriet. -

FÖRINTELSENS RÖDA NEJLIKA Förintelsens Röda Nejlika Och Omvärlden, För Såväl Som Ny Äldre Viktig Forskning

Ulf Zander Raoul Wallenberg har fått status som en av andra världskrigets främsta FÖRINTELSENS RÖDA NEJLIKA hjältar tack vare de insatser han gjorde i Budapest 1944–1945 för att rädda judar undan Förintelsen. Samtidigt är hans öde förknippat med Raoul Wallenberg som historiekulturell symbol fångenskap och undergång i Sovjetunionen. I Förintelsens röda nejlika skriver Ulf Zander om den förändrade synen på Wallenberg i Sverige, Ungern och USA under efterkrigstiden. Diskussioner om det politiska och diplomatiska spelet kring honom är sammanflätat med olika kulturella gestaltningar av Wallenberg och hans öde. FÖRINTELSENS NEJLIKA RÖDA av Ulf Zander Ulf Zander är professor i historia med inriktning mot historiedidaktik vid Malmö högskola. Forum för levande historias skriftserie är en länk mellan forskarsamhället och omvärlden, för såväl ny som äldre viktig forskning. Syftet är att ge SKRIFT # 12:2012 spridning åt centrala forskningsresultat inom myndighetens kärnområden. Forum för levande historia FÖRINTELSENS RÖDA NEJLIKA Raoul Wallenberg som historiekulturell symbol av Ulf Zander SKRIFT # 12:2012 Forum för levande historia »Förintelsens röda nejlika – Raoul Wallenberg som historiekulturell symbol« ingår i Forum för levande historias skriftserie Författare Ulf Zander Redaktör Ingela Karlsson Ansvarig utgivare Eskil Franck Grafisk formgivning Ritator Omslagfoto Olivia Jeczmyk Foto Överst s. 186 Matti Östling Underst s. 186: Olivia Jeczmyk s. 127 och 132: Ulf Zander Övriga: Scanpix Tryck Edita, Västerås 2012 Forum för levande historia Box 2123, -

Russia's Strategy for Influence Through Public Diplomacy and Active

Journal of Strategic Studies ISSN: 0140-2390 (Print) 1743-937X (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fjss20 Russia’s strategy for influence through public diplomacy and active measures: the Swedish case Martin Kragh & Sebastian Åsberg To cite this article: Martin Kragh & Sebastian Åsberg (2017): Russia’s strategy for influence through public diplomacy and active measures: the Swedish case, Journal of Strategic Studies, DOI: 10.1080/01402390.2016.1273830 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2016.1273830 Published online: 05 Jan 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 20943 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fjss20 Download by: [95.43.25.137] Date: 11 January 2017, At: 10:08 THE JOURNAL OF STRATEGIC STUDIES, 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2016.1273830 Russia’s strategy for influence through public diplomacy and active measures: the Swedish case Martin Kragha,b and Sebastian Åsbergc aHead of Russia and Eurasia Programme, Swedish Institute of International Affairs, Stockholm; bUppsala Centre for Russian and Eurasian Studies, Uppsala University, Sweden; cRussia and Eurasia Studies, Swedish Institute of International Affairs ABSTRACT Russia, as many contemporary states, takes public diplomacy seriously. Since the inception of its English language TV network Russia Today in 2005 (now ‘RT’), the Russian government has broadened its operations to include Sputnik news websites in several languages and social media activities. Moscow, however, has also been accused of engaging in covert influence activities – behaviour historically referred to as ‘active measures’ in the Soviet KGB lexicon on political warfare.