"Eight Revolutionary Model Operas" in China's Great Cultural Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

China Study Journal

CHINA STUDY JOURNAL CHINA DESK Churches Together in Britain and Ireland Sh- churches ìogethe AU r IN BRITAIN AND I II i u « 0® China Study Journal Autumn/Winter 2008 Editorial Address: China Desk, Churches Together in Britain and Ireland, Bastille Court, 2 Paris Garden, London, SEI 8ND, United Kingdom Email: [email protected] ISSN 0956-4314 Cover: Nial Smith Design, from: Shen Zhou (1427-1509), Poet on a Mountain Top, Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). Album leaf mounted as a hand scroll, ink and water colour on paper, silk mount, image 15 lA x 23 % inches (38.74 x 60.33cm). © "The Nelson-Arkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Purchase: Nelson Trust, 46-51/2. Photograph by Robert Newcombe. Layout by raspberryhmac - www.raspberryhmac.co.uk Contents Editorial Section 1 Articles Zhuo Xinping Societal Changes and Religious Reconstruction in Contemporary China Li Shunhua Another Aspect of Chinese Rural Christianity — Based on a field survey of a rural church in north Henan province Chen Shengbai A Minority amongst a minority: an investigation into the situation of [Protestant] Christianity in Southern Gansu Section 2 Documentation Editor: Edmond Tang Managing Editor: Lawrence Braschi Translators: Cinde Lee, Lawrence Breen, Alison Hardie, Lawrence Braschi Abbreviations ANS : Amity News Service (HK) CASS : Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (Beijing) CCBC : Chinese Catholic Bishops' Conference CCC : China Christian Council CCPA : Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association CM : China Muslim (Journal) CPPCC : Chinese People's Consultative Conference FY : Fa Yin (Journal of the Chinese Buddhist Assoc.) SCMP : South China Morning Post(HK) SE : Sunday Examiner (HK) TF : Tian Feng (Journal of the China Christian Council) TSPM : Three-Seif Patriotic Movement UCAN : Union of Catholic Asian News ZENIT : Catholic News Agency ZG DJ : China Taoism (Journal) ZGTZJ : Catholic Church in China (Journal of Chinese Catholic Church) Note: the term lianghui is used in this journal to refer to the joint committees of the TSPM and CCC. -

002170196E1c16a28b910f.Pdf

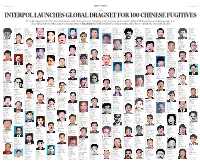

6 THURSDAY, APRIL 23, 2015 DOCUMENT CHINA DAILY 7 JUSTICE INTERPOL LAUNCHES GLOBAL DRAGNET FOR 100 CHINESE FUGITIVES It’s called Operation Sky Net. Amid the nation’s intensifying antigraft campaign, arrest warrants were issued by Interpol China for former State employees and others suspected of a wide range of corrupt practices. China Daily was authorized by the Chinese justice authorities to publish the information below. Language spoken: Liu Xu Charges: Place of birth: Anhui property and goods Language spoken: Zeng Ziheng He Jian Qiu Gengmin Wang Qingwei Wang Linjuan Chinese, English Sex: Male Embezzlement Language spoken: of another party by Chinese Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Female Charges: Date of birth: Chinese, English fraud Charges: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Accepting bribes 07/02/1984 Charges: Embezzlement Embezzlement 15/07/1971 14/11/1965 15/05/1962 03/01/1972 17/07/1980 Place of birth: Beijing Place of birth: Henan Language spoken: Place of birth: Place of birth: Place of birth: Language spoken: Language spoken: Chinese Zhejiang Jinan, Shandong Jilin Chinese, English Chinese Charges: Graft Language spoken: Language spoken: Language spoken: Charges: Corruption Charges: Chinese Chinese, English Chinese Embezzlement Charges: Contract Charges: Commits Charges: fraud, and flight of fraud by means of a Misappropriation of Yang Xiuzhu 25/11/1945 Place of birth: Chinese Zhang Liping capital contribution Chu Shilin letter of credit Dai Xuemin public funds Sex: Female -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Across the Geo-political Landscape Chinese Women Intellectuals’ Political Networks in the Wartime Era 1937-1949 Guo, Xiangwei Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 Across the Geo-political Landscape: Chinese Women Intellectuals’ Political -

April 20, 1961 Memorandum of Conversation, Comrade Abdyl Kellezi with Comrade Zhou Enlai

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified April 20, 1961 Memorandum of Conversation, Comrade Abdyl Kellezi with Comrade Zhou Enlai Citation: “Memorandum of Conversation, Comrade Abdyl Kellezi with Comrade Zhou Enlai,” April 20, 1961, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Central State Archive, Tirana, AQPPSH-MPKK-V. 1961, L. 13, D. 6. Obtained by Ana Lalaj and translated by Enkel Daljani. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/111817 Summary: Zhou Enlai expressed China's opinions on the result of the meeting of the Political Consultative Committee of the Warsaw Pact, China's support of the principles of Marxism-Leninism in several Soviet-Albanian conflicts. They also discussed issues of economic and military assistance. Original Language: Albanian Contents: English Translation At the meeting there were also present: From our side, comrade Mihal Prifti, from the Chinese side the comrades Deng Xiaoping, Luo Ruiqing, Vice Premier of the State Council and Chief of Staff, and Wu Xiuquan, Deputy Director of the CCP CC International Department. In the lunch that was given after the talks there was also comrade Tan Zhenlin, member of the Political Bureau of the CCP CC and dealing with agriculture issues, as well as Comrade Li Xiannian. Comrade Zhou Enlai: We took a look at the minutes of the meeting between [Chairman of the Ministerial Council and Member of the Political Bureau of the ALP CC] Comrade Mehmet Shehu and comrade Luo Shigao that they had after the meeting of the Political Consultative Committee of the Warsaw Pact that was held in Moscow. In addition, we have also seen the minutes of your meeting with comrade Li Xiannian. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Deng Xiaoping in the Making of Modern China

Teaching Asia’s Giants: China Crossing the River by Feeling the Stones Deng Xiaoping in the Making of Modern China Poster of Deng Xiaoping, By Bernard Z. Keo founder of the special economic zone in China in central Shenzhen, China. he 9th of September 1976: The story of Source: The World of Chinese Deng Xiaoping’s ascendancy to para- website at https://tinyurl.com/ yyqv6opv. mount leader starts, like many great sto- Tries, with a death. Nothing quite so dramatic as a murder or an assassination, just the quiet and unassuming death of Mao Zedong, the founding father of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). In the wake of his passing, factions in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) competed to establish who would rule after the Great Helmsman. Pow- er, after all, abhors a vacuum. In the first corner was Hua Guofeng, an unassuming functionary who had skyrocketed to power under the late chairman’s patronage. In the second corner, the Gang of Four, consisting of Mao’s widow, Jiang September 21, 1977. The Qing, and her entourage of radical, leftist, Shanghai-based CCP officials. In the final corner, Deng funeral of Mao Zedong, Beijing, China. Source: © Xiaoping, the great survivor who had experi- Keystone Press/Alamy Stock enced three purges and returned from the wil- Photo. derness each time.1 Within a month of Mao’s death, the Gang of Four had been imprisoned, setting up a showdown between Hua and Deng. While Hua advocated the policy of the “Two Whatev- ers”—that the party should “resolutely uphold whatever policy decisions Chairman Mao made and unswervingly follow whatever instructions Chairman Mao gave”—Deng advocated “seek- ing truth from facts.”2 At a time when China In 1978, some Beijing citizens was reexamining Mao’s legacy, Deng’s approach posted a large-character resonated more strongly with the party than Hua’s rigid dedication to Mao. -

Three Prominences1

THE THREE PROMINENCES1 Yizhong Gu The political-aesthetic principle of the “three prominences” (san tuchu 三突出) was the formula foremost in governing proletarian literature and art during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76) (hereafter CR). In May 1968, Yu Huiyong 于会泳 initially proposed and defined the principle in this way: Among all characters, give prominence to the positive characters; among the positive characters, give prominence to the main heroic characters; among the main characters, give prominence to the most important character, namely, the central character.2 As the main composer of the Revolutionary Model Plays, Yu Hui- yong had gone through a number of ups and downs in the official hierarchy before finally receiving favor from Jiang Qing 江青, wife of Mao Zedong. Yu collected plenty of Jiang Qing’s concrete but scat- tered directions on the Model Plays and tried to summarize them in an abstract and formulaic pronouncement. The principle of three prominances was supposed to be applicable to all the Model Plays and thus give guidance for the creation of future proletarian artworks. Summarizing the gist of Jiang’s instruction, Yu observed, “Comrade Jiang Qing lays strong emphasis on the characterization of heroic fig- ures,” and therefore, “according to Comrade Jiang Qing’s directions, we generalize the ‘three prominences’ as an important principle upon which to build and characterize figures.”3 1 This essay owes much to invaluable encouragement and instruction from Profes- sors Ban Wang of Stanford University, Tani Barlow of Rice University, and Yomi Braester of the University of Washington. 2 Yu Huiyong, “Rang wenyi wutai yongyuan chengwei xuanchuan maozedong sixiang de zhendi” (Let the stage of art be the everlasting front to propagate the thought of Mao Zedong), Wenhui Bao (Wenhui daily) (May 23, 1968). -

1 EDWARD A. MCCORD Professor

EDWARD A. MCCORD Professor of History and International Affairs The George Washington University CONTACT INFORMATION Office: 1957 E Street, NW, Suite 503 Sigur Center for Asian Studies The George Washington University Washington, D.C. 20052 Phone: 202-994-5785 Fax: 202-994-6096 Home: 807 Philadelphia Ave. Silver Spring, MD 20910 Phone: 301-588-6948 Email: [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. University of Michigan, History, 1985 M.A. University of Michigan, History, 1978 B.A. Summa Cum Laude, Marian College, History, 1973 OVERSEAS STUDY AND RESEARCH 1992-1993 Research, People's Republic of China Summer 1992 Inter-University Chinese Language Program, Taipei, Taiwan 1981-1983 Dissertation Research, People's Republic of China 1975-1977 Inter-University Chinese Language Program, Taipei, Taiwan ACADEMIC POSITIONS Professor of History and International Affairs, Elliott School of International Affairs, The George Washington University. July 2015 to present (Associatte Professor of History and International Affairs, September 1994 to July 2015). Director, Taiwan Education and Research Program, Sigur Center for Asian Studies, The George Washington University. May 2004 to present. Director, Sigur Center for Asian Studies, The George Washington University, August 2011 to June 2014. Deputy Chair, History Department, The George Washington University, July 2009 to August 2011. 1 Senior Associate Dean for Management and Planning, Elliott School of International Affairs, The George Washington University. July 2005 to August 2006. Associate Dean for Faculty and Student Affairs, Elliott School of International Affairs, The George Washington University. January 2004 to June 2005. Associate Director, Sigur Center for Asian Studies, The George Washington University. July-December 2003. Acting Dean, Elliott School of International Affairs, The George Washington University. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript Pas been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissenation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from anytype of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material bad to beremoved, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with smalloverlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back ofthe book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell &Howell Information Company 300North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106-1346 USA 313!761-47oo 800:521·0600 THE LIN BIAO INCIDENT: A STUDY OF EXTRA-INSTITUTIONAL FACTORS IN THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY AUGUST 1995 By Qiu Jin Dissertation Committee: Stephen Uhalley, Jr., Chairperson Harry Lamley Sharon Minichiello John Stephan Roger Ames UMI Number: 9604163 OMI Microform 9604163 Copyright 1995, by OMI Company. -

ILO Fundamental Conventions and Chinese Labor Law: from a Comparative Perspective

ILO Fundamental Conventions and Chinese Labor Law: From a Comparative Perspective Qiu Yang1 Abstract: In this article, through a comparative study between ILO fundamental Conventions and Chinese labor law, the writer points out several problems and shortcomings embodied in Chinese labor law. This article analyzes the status of Chinese trade unions and questions their ability to protect the interests of the Chinese working class. As for collective bargaining, the writer reviews the relevant Chinese labor law and discovers the reasons for the ineffectiveness of the collective bargaining system in China. In the case of forced labor, the writer critically evaluates three kinds of forced labor in today‟s China. With regard to child labor, according to a review on relevant legislations, the writer points out certain internal legislation as contradictory. As far as discrimination with regard to employment and occupation is concerned, after a general overview on related ILO conventions and Chinese legislation, the writer focuses on employment based on social origin in China, using a case study on Chinese farmer workers. In the writer‟s understanding, as a vulnerable group, farmer workers have not received enough attention and special protection from Chinese labor legislation. ILO Fundamental Conventions and Chinese Labor Law: From a Comparative Perspective ........................18 I. Introduction ..............................................................................................................................................19 II.