Shock and Naturalization - an Inquiry Into the Perception of Modernity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spirits of the Age: Ghost Stories and the Victorian Psyche

SPIRITS OF THE AGE: GHOST STORIES AND THE VICTORIAN PSYCHE Jen Cadwallader A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Laurie Langbauer Jeanne Moskal Thomas Reinert Beverly Taylor James Thompson © 2009 Jen Cadwallader ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JEN CADWALLADER: Spirits of the Age: Ghost Stories and the Victorian Psyche (Under the direction of Beverly Taylor) “Spirits of the Age: Ghost Stories and the Victorian Psyche” situates the ghost as a central figure in an on-going debate between nascent psychology and theology over the province of the psyche. Early in the nineteenth century, physiologists such as Samuel Hibbert, John Ferriar and William Newnham posited theories that sought to trace spiritual experiences to physical causes, a move that participated in the more general “attack on faith” lamented by intellectuals of the Victorian period. By mid-century, various of these theories – from ghosts as a form of “sunspot” to ghost- seeing as a result of strong drink – had disseminated widely across popular culture, and, I argue, had become a key feature of the period’s ghost fiction. Fictional ghosts provided an access point for questions regarding the origins and nature of experience: Ebenezer Scrooge, for example, must decide if he is being visited by his former business partner or a particularly nasty stomach disorder. The answer to this question, here and in ghost fiction across the period, points toward the shifting dynamic between spiritual and scientific epistemologies. -

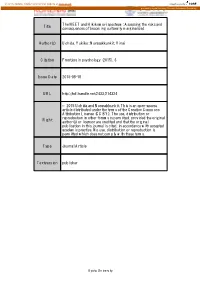

Title the NEET and Hikikomori Spectrum

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and Title consequences of becoming culturally marginalized. Author(s) Uchida, Yukiko; Norasakkunkit, Vinai Citation Frontiers in psychology (2015), 6 Issue Date 2015-08-18 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/214324 © 2015 Uchida and Norasakkunkit. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original Right author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 18 August 2015 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01117 The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and consequences of becoming culturally marginalized Yukiko Uchida 1* and Vinai Norasakkunkit 2 1 Kokoro Research Center, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan, 2 Department of Psychology, Gonzaga University, Spokane, WA, USA An increasing number of young people are becoming socially and economically marginalized in Japan under economic stagnation and pressures to be more globally competitive in a post-industrial economy. The phenomena of NEET/Hikikomori (occupational/social withdrawal) have attracted global attention in recent years. Though the behavioral symptoms of NEET and Hikikomori can be differentiated, some commonalities in psychological features can be found. Specifically, we believe that both NEET and Hikikomori show psychological tendencies that deviate from those Edited by: Tuukka Hannu Ilmari Toivonen, governed by mainstream cultural attitudes, values, and behaviors, with the difference University of London, UK between NEET and Hikikomori being largely a matter of degree. -

1 Urusei Yatsura Disc 21, Episodes 79 – 82

URUSEI YATSURA DISC 21, EPISODES 79 – 82 Episode 79, Story 102: The House of Mendou - Summer X'mas “The Young Master's combat-shooting skills are much improved!” - shooting instructor. Fans of Japanese cinema might notice a clever visual reference and get a good laugh - The instructor here is modeled after Tanaka Kunie, one of the most popular Japanese actors. “Hit!” - a banner held by Ataru. A trivial, visual pun here is that Ataru is holding a banner that reads “Hit!”, which is “Atari!” in Japanese. “That's the Kuroko Group's Cargocopter squadron, sir.” - Mendou's employee. “Don't panic! They're Kuroko. Think of them as a part of the background.” - Megane. The Kuroko Group (“Kuroko-gumi”) in UY has a basis in real life. In traditional Japanese theater, “kuroko” are stage assistants covered in black veils who act as invisible puppeteers, operate props or change sets, etc. They are officially invisible and not to be noticed. Historically, Kuroko evolved during the Edo period, so their speech patterns are archaic at times. “What Fireworks!”, for instance, is based on an Edo-era phrase, “Tamaya!,” which alluded to a famous fireworks shop. The main humor with these Kuroko in UY is that they perform ‘invisible’ acts in such a blatantly obvious manner! “As you know, in high school baseball tournaments, there are spring tournaments and summer tournaments.” – Kuroko. Needless to say, high school baseball tournaments are a very big thing in Japan, similar in popularity to collegiate basketball in the US. Scouts from professional teams seek new players during these events. -

Birthdays Susan Cole

Volume 29 Number 4 Issue 346 September 2016 A WORD FROM THE EDITOR Kimber Groman (graphic artist) and others August was Worldcon in Kansas City. MidAmericon 2 $25 for 3 days pre con, $30 at the door had a lot going on. There were two Hugo Ceremonies. There spacecoastcomiccon.com were a lot of exhibits and of course 5,000 items on the program. I did a lot of work pre-con and got to see aKansas City at the Animate! Florida same time. The con was great and I need to start working on my September 16-19 report. Port St Lucie Civic Center This month I may checkout some local events. I may try 9221 SE Civiv Center Place to squeeze in a review. Port St Lucie FL As always I am willing to take submissions. Guests: Tony Oliver (Rick Hunter, Robotech) See you next month. Julie Dolan (Star Wars: Rebels) Erica Mendez (Ryoka Matoi, Kill La Kill) Events and many more $55 for 3 days pre con Comic Book Connection animateflorida.com/ September 3-4 Holiday Inn Treasure Comic Con 2300 SR 16 September 16-19 ST Augustine, FL 32084 Greater Fort Lauderdale Convention Center $5 at the door 1950 Eisenhower Blvd, thecomicbookconnection.com Fort Lauderdale, FL 33316 Guests: Space Coast Comic Con Billy West (Phil Fry, Futurama) September 9-11 Kristin Bauer (Maleficient, Once Upon a Space Coast Convention Center Time) 301 Tucker Ln Beverly Elliot(Granny, Once Upon a Time) Cocoa, FL 32926 and many more Guests: Terance Baker (comic artist) $35 for 3 days pre con, $40 at the door Jake Estrada (comic artist) www.treasurecoastcomiccon.com Fusion Con II September 17 Birthdays New Port Richey Recreation & Aquatic Center 6630 Van Buren St Susan Cole - Sept. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

Nintendo Famicom

Nintendo Famicom Last Updated on September 23, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments '89 Dennou Kyuusei Uranai Jingukan 10-Yard Fight Irem 100 Man Dollar Kid: Maboroshi no Teiou Hen Sofel 1942 Capcom 1943: The Battle of Valhalla Capcom 1943: The Battle of Valhalla: FamicomBox Nintendo 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu C*Dream 2010 Street Fighter Capcom 4 Nin uchi Mahjong Nintendo 8 Eyes Seta 8bit Music Power Final: Homebrew Columbus Circle A Ressha de Ikou Pony Canyon Aa Yakyuu Jinsei Icchokusen Sammy Abadox: Jigoku no Inner Wars Natsume Abarenbou Tengu Meldac Aces: Iron Eagle III Pack-In-Video Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Dragons of Flame Pony Canyon Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Heroes of the Lance Pony Canyon Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Hillsfar Pony Canyon Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Pool of Radiance Pony Canyon Adventures of Lolo HAL Laboratory Adventures of Lolo II HAL Laboratory After Burner Sunsoft Ai Sensei no Oshiete: Watashi no Hoshi Irem Aigiina no Yogen: From The Legend of Balubalouk VIC Tokai Air Fortress HAL Laboratory Airwolf Kyugo Boueki Akagawa Jirou no Yuurei Ressha KING Records Akira Taito Akuma Kun - Makai no Wana Bandai Akuma no Shoutaijou Kemco Akumajou Densetsu Konami Akumajou Dracula Konami Akumajou Special: Boku Dracula Kun! Konami Alien Syndrome Sunsoft America Daitouryou Senkyo Hector America Oudan Ultra Quiz: Shijou Saidai no Tatakai Tomy American Dream C*Dream Ankoku Shinwa - Yamato Takeru Densetsu Tokyo Shoseki Antarctic Adventure Konami Aoki Ookami to Shiroki Mejika: Genchou Hishi Koei Aoki Ookami to Shiroki Mejika: Genghis Khan Koei Arabian Dream Sherazaado Culture Brain Arctic Pony Canyon Argos no Senshi Tecmo Argus Jaleco Arkanoid Taito Arkanoid II Taito Armadillo IGS Artelius Nichibutsu Asmik-kun Land Asmik ASO: Armored Scrum Object SNK Astro Fang: Super Machine A-Wave Astro Robo SASA ASCII This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Lyric Forms of the Literati Mind: Yosa Buson, Ema Saikō, Masaoka Shiki and Natsume Sōseki Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/97g9d23n Author Mewhinney, Matthew Stanhope Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Lyric Forms of the Literati Mind: Yosa Buson, Ema Saikō, Masaoka Shiki and Natsume Sōseki By Matthew Stanhope Mewhinney A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Language in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Alan Tansman, Chair Professor H. Mack Horton Professor Daniel C. O’Neill Professor Anne-Lise François Summer 2018 © 2018 Matthew Stanhope Mewhinney All Rights Reserved Abstract The Lyric Forms of the Literati Mind: Yosa Buson, Ema Saikō, Masaoka Shiki and Natsume Sōseki by Matthew Stanhope Mewhinney Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Language University of California, Berkeley Professor Alan Tansman, Chair This dissertation examines the transformation of lyric thinking in Japanese literati (bunjin) culture from the eighteenth century to the early twentieth century. I examine four poet- painters associated with the Japanese literati tradition in the Edo (1603-1867) and Meiji (1867- 1912) periods: Yosa Buson (1716-83), Ema Saikō (1787-1861), Masaoka Shiki (1867-1902) and Natsume Sōseki (1867-1916). Each artist fashions a lyric subjectivity constituted by the kinds of blending found in literati painting and poetry. I argue that each artist’s thoughts and feelings emerge in the tensions generated in the process of blending forms, genres, and the ideas (aesthetic, philosophical, social, cultural, and historical) that they carry with them. -

Soseki's Meian Revisited

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Soseki’s Meian Revisited: A Fresh Look at a Modem Classic Valdo H. viglielmo INE decades after Natsume Soseki’s death on December 9, 1916, and hence also nine decades after the serialization, in the Asahi Shimbun, of Nhis last novel Meian was broken off on December 14 of that year, twenty- two sections having remained after he collapsed on November 22, both Soseki the author and his unfinished work are the objects of intense scrutiny that gives no sign whatsoever of abating. Every enquete, or anketo 7 yhr— b, of the most favorite author of the Japanese reading public, places Soseki as num ber one, always outranking even Mori Ogai (1862-1922) and the two Nobel laureates in literature Kawabata Yasunari WlStV (1899-1972) and Oe Kenzaburo (1935-). Although Meian is not always similarly ranked as the most favorite Soseki novel, it is never absent from among the three or four most admired of his novels. (Clearly Kokoro ’ ’ 7 [Heart, 1914] and Michikusa iSM [Grass on the Way side, 1915] have their ardent admirers.) But I hope I may be forgiven for considering Meian the finest of Soseki’s works, not only because I translated it into English but also because, having explored Soseki’s life and work, or as the French would have it, his vie et oeu vre, for well over half a century, I think I am well qualified to assess the rel ative merits of his many superb works. With that as a preface, I wish to revisit this unfinished novel and attempt to persuade prospective readers -

Phantasmagoria: Ghostly Entertainment of the Victorian Britain

Phantasmagoria: Ghostly entertainment of the Victorian Britain Yurie Nakane / Tsuda College / Tokyo / Japan Abstract Phantasmagoria is an early projection show using an optical instrument called a magic lantern. Brought to Britain from France in 1801, it amused spectators by summoning the spirits of ab- sent people, including both the dead and the living. Its form gradually changed into educational amusement after it came to Britain. However, with the advent of spiritualism, its mysterious na- ture was re-discovered in the form of what was called ‘Pepper’s Ghost’. Phantasmagoria was reborn in Britain as a purely ghostly entertainment, dealing only with spirits of the dead, be- cause of the mixture of the two notions brought from France and the United States. This paper aims to shed light on the role that phantasmagoria played in Britain during the Victorian period, how it changed, and why. Through observing the transnational history of this particular form of entertainment, we can reveal a new relationship between the representations of science and superstitions. Keywords Phantasmagoria, spiritualism, spectacle, ghosts, the Victorian Britain, superstitions Introduction Humans have been mesmerized by lights since ancient times. Handling lights was considered a deed conspiring with magic or witchcraft until the sixteenth century, owing to its sanctified appearance; thus, some performers were put in danger of persecution. At that time, most people, including aristocrats, were not scientifically educated, because science itself was in an early stage of development. However, the flourishing thought of the Enlightenment in the eighteenth century altered the situation. Entering the age of reason, people gradually came to regard illusions as worthy of scientific examination. -

Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know

1 Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know Edited by Parissa Haghirian Sophia University Tokyo, Japan 2 Contents About this Book ......................................................................................... 4 The Editor ................................................................................................ 5 Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know ................................................. 6 Contributors of This Book ............................................................................ 94 Bibliography ............................................................................................ 96 Further Reading on Japanese Management .................................................... 102 3 About this Book This book is the result of one of my “Management in Japan” classes held at the Faculty of Liberal Arts at Sophia University in Tokyo. Students wrote this dictionary entries, I edited and updated them. The document is now available as a free e-book at my homepage www.haghirian.com. We hope that this book improves understanding of Japanese management and serves as inspiration for anyone interested in the subject. Questions and comments can be sent to [email protected]. Please inform the editor if you plan to quote parts of the book. Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know Edited by Parissa Haghirian First edition, Tokyo, October 2019 4 The Editor Parissa Haghirian is Professor of International Management at Sophia University in Tokyo. She lives and works in Japan since 2004 -

The Tragic Sense of Life by Miguel De Unamuno

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Tragic Sense Of Life, by Miguel de Unamuno This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Tragic Sense Of Life Author: Miguel de Unamuno Release Date: January 8, 2005 [EBook #14636] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TRAGIC SENSE OF LIFE *** Produced by David Starner, Martin Pettit and the PG Online Distributed Proofreading Team TRAGIC SENSE OF LIFE MIGUEL DE UNAMUNO translator, J.E. CRAWFORD FLITCH DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC New York This Dover edition, first published in 1954, is an unabridged and unaltered republication of the English translation originally published by Macmillan and Company, Ltd., in 1921. This edition is published by special arrangement with Macmillan and Company, Ltd. The publisher is grateful to the Library of the University of Pennsylvania for supplying a copy of this work for the purpose of reproduction. Standard Book Number: 486-20257-7 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 54-4730 Manufactured in the United States of America Dover Publications, Inc. 180 Varick Street New York, N.Y. 10014 CONTENTS INTRODUCTORY ESSAY AUTHOR'S PREFACE I THE MAN OF FLESH AND BONE Philosophy and the concrete man—The man Kant, the man Butler, and the man Spinoza—Unity and continuity of the person—Man an end not a means—Intellectual necessities