Donald-Rooum-And-Freedom-Press-Ed-What-Is-Anarchism-An-Introduction.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue 2021 Welcome to the FREEDOM CATALOGUE

anarchist publishing Est. 1886 Catalogue 2021 wELCOME TO THE FREEDOM CATALOGUE Anarchism is almost certainly the most interesting political movement to have slipped under the radar of public discourse. It is rarely pulled up in today’s media as anything other than a curio or a threat. But over the course of 175 years since Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s declaration “I am an anarchist” this philosophy of direct action and free thought has repeatedly changed the world. From Nestor Makhno’s legendary war on both Whites and Reds in 1920s Ukraine, to the Spanish Civil War, to transformative ideals in the 1960s and street-fought antifascism in the 1980s, anarchism remains a vital part of any rounded understanding of humanity’s journey from past to present, let alone the possibilities for its future. For most of that time there has been Freedom Featuring books from Peter Kropotkin, Marie Press. Founded in 1886, brilliant thinkers past and Louise Berneri, William Blake, Errico Malatesta, Colin present have published through Freedom, allowing Ward and many more, this catalogue offers much us to present today a kaleidoscope of classic works of what you might need to understand a fascinating from across the modern age. creed. shop orders trade orders You can order online, by email, phone Trade orders come from Central Books, who or post (details below). Our business offer 33% stock discounts as standard. Postage hours are 10am-6pm, Monday to is free within the UK, with £2.50 extra for orders Saturday. from abroad — per order not per item. You can pay via Paypal on our website. -

The Ethical Record Vol

ISSN 0014-1690 The Ethical Record Vol. 98 No. 4 El April 1993 THE STORY OF THE SOCIETY Nicholas Walter 3 THE POLITICS OF SIMONE WEIL: THEORY • AND PRACTICE Christopher Hampton 10 TOYNBEE HALL: SELF- SERVING OR ACCOUNTABLE? Prof. Gerald Vinten 14 SOCIAL CHANGE Margaret Chisman 16 VIEWPOINTS M Neocleous, P Cadogan, Alireza. 16 SCIENCE AND THE EDITORIAL — HIGH HUMANIST HOPES GENERAL READER Peter Reales 21 In our 200 year progress from dissident congregation to humanist society, we have shed, ATHEIST ASSOCIATION? along with the dogmas of religion, its symbols Harry Whitby 24 and trappings too. Nevertheless, the apparently ephemeral event of the release of 200 balloons ATTACKS ON SCIENCE - on the 14th February 1993 can perhaps be seen in retrospect as a symbolic act. GOOD AND BAD ColM Mills 25 The event was the brainchild of Michael SHOULD HUMANISTS Newman; he felt the need to commemorate the PLAY DICE? bicentenary in a more graphic way than could be Ronald Skene 29 done by speeches alone. As we stood in Red Lion Square, watching the balloons soar ever ETHICAL SOCIETY higher over London, some of us may have been EVENTS 31 moved to wonder... Could those balloons, imprinted with SPES — FREETHOUGHT — 1793-1993 and gradually diffusing over the capital, symbolise the 'dissemination of ethical principles' for which the Society still stands and for which the world has such sore need? SOUTH PLACE ETHICAL SOCIETY Conway Hall Humanist Centre 25 Red Lion Square, London WC1R 4RL. Telephone: 071-831 7723 Trustees Louise Booker, John Brown, Anthony Chapman, Peter Heales, Don Liversedge, Ray Lovecy, Ian MacKillop, Barbara Smoker, Harry Stopes-Roe. -

Rebel Alliances

Rebel Alliances The means and ends 01 contemporary British anarchisms Benjamin Franks AK Pressand Dark Star 2006 Rebel Alliances The means and ends of contemporary British anarchisms Rebel Alliances ISBN: 1904859402 ISBN13: 9781904859406 The means amiemls 01 contemllOranr British anarchisms First published 2006 by: Benjamin Franks AK Press AK Press PO Box 12766 674-A 23rd Street Edinburgh Oakland Scotland CA 94612-1163 EH8 9YE www.akuk.com www.akpress.org [email protected] [email protected] Catalogue records for this book are available from the British Library and from the Library of Congress Design and layout by Euan Sutherland Printed in Great Britain by Bell & Bain Ltd., Glasgow To my parents, Susan and David Franks, with much love. Contents 2. Lenini8t Model of Class 165 3. Gorz and the Non-Class 172 4. The Processed World 175 Acknowledgements 8 5. Extension of Class: The social factory 177 6. Ethnicity, Gender and.sexuality 182 Introduction 10 7. Antagonisms and Solidarity 192 Chapter One: Histories of British Anarchism Chapter Four: Organisation Foreword 25 Introduction 196 1. Problems in Writing Anarchist Histories 26 1. Anti-Organisation 200 2. Origins 29 2. Formal Structures: Leninist organisation 212 3. The Heroic Period: A history of British anarchism up to 1914 30 3. Contemporary Anarchist Structures 219 4. Anarchism During the First World War, 1914 - 1918 45 4. Workplace Organisation 234 5. The Decline of Anarchism and the Rise of the 5. Community Organisation 247 Leninist Model, 1918 1936 46 6. Summation 258 6. Decay of Working Class Organisations: The Spani8h Civil War to the Hungarian Revolution, 1936 - 1956 49 Chapter Five: Anarchist Tactics Spring and Fall of the New Left, 7. -

Andthe Anarchists Other Issues of "Anarchy"L Gontents of Il0

AilARCHYJ{0.109 3shillings lSpence 40cents "-*"*"'"'r ,Eh$ Russell andthe Anarchists Other issues of "Anarchy"l Gontents of il0. 109 Please note that the following issues are out of print: I to 15 inclusive, 26,27, 38, ANiARCHY 109 (Vol l0 No 3) MARCH 1970 65 March 1970 39, 66, 89, 90, 96, 98, 102. Vol. I 1961l. 1. Sex-and-Violence; 2. Workers' control; 3. What does anar- chism mcarr today?: 4. Deinstitutioni- sariorr; 5. Spain; 6. Cinema; 7. Adventure playgrourrd; 3. Anthropology; 9. Prison; 10. [ndustrial decentralisation. Neither God nor Master V. Ncill; 12. Who are the anarchists?; 13. Richard Drinnon 65 Direct action; 14. Disobcdience; 15. David Wills; 16. Ethics of anarchism; 17. Lum- lleilther God pcn proletariat ; I {l.Comprehensive schools; Russell and the anarchists 19. 'Ihcatrc; 20. Non-violence; 21. Secon- dary Vivian Harper 68 modern; 22. Marx and Bakunin. nor Master Vol. 3. l96f : 23. Squatters; 24. Com- murrity of scholars; 25. Cybernetics; 26. RIOHABD DNIililOI{ Counter-culture 'l'horcarri 27. Yor-rth; 28. Future of anar- chisml 2t). Spies for peace;30. Com- Kingsley lAidmer 18 rnurrity workshop; 31. Self-organising systcmsi 32. Orimc; 33. Alex Comfort; Kropotkin and his memoirs J4. Scicnce fiction. Nicolas Walter 84 .17. I won't votc; 38. Nottingham; 39. Tsoucn ITS Roors ARE DBEpLy BURIED, modern anarchism I Iorncr l-ancl 40. Unions; 41. Land; dates from the entry of the Bakuninists into the First Inter- 42. India; 43. Parents and teachers; 44, Observations on eNanttnv 104 l'rarrsport; 45. Thc Greeks;46. Anarchisrn national just a hundred years ago. -

Read Book Demanding the Impossible: a History of Anarchism

DEMANDING THE IMPOSSIBLE: A HISTORY OF ANARCHISM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Peter Marshall | 818 pages | 01 Feb 2010 | PM Press | 9781604860641 | English | Oakland, United States Demanding the Impossible | The Anarchist Library Click here for one-page information sheet on this product. Cart Contents. Recent Posts. Price: 0. Add To Wishlist. Overview Tell a Friend. Send Message. Anarchism Books Combo Pack. A fantastic combo pack of anarchist philosophies, conversations, history and reference not to be missed! Peter Marshall Navigating the broad "river of anarchy," from Taoism to Situationism, from anarcho-syndicalists to anarcha-feminists, this volume is an authoritative and lively study of a widely misunderstood subject. What Is Anarchism? Donald Rooum This book is an introduction to the development of anarchist thought, useful not only to propagandists and proselytizers of anarchism but also to teachers and students, and to all who want to uncover the basic core of anarchism. Editors: Raymond Craib and Barry Maxwell A collection of essays on the questions of geographical and political peripheries in anarchist theory. Voices of the Paris Commune. Presenting a balanced and critical survey, the detailed document covers not only classic anarchist thinkers--such as Godwin, Proudhon, Bakunin, Kropotkin, Reclus, and Emma Goldman--but also other libertarian figures, such as Nietzsche, Camus, Gandhi, Foucault, and Chomsky. Essential reading for anyone wishing to understand what anarchists stand for and what they have achieved, this fascinating account also includes an epilogue that examines the most recent developments, including postanarchism and anarcho-primitivism as well as the anarchist contributions to the peace, green, and global justice movements of the 21st century. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Herbert Read to T.S. Eliot: 1 October 1949: Herbert Read Archive, University of Victoria (hereafter HRAUV), HR/TSE-170. 2. Herbert Read, The Contrary Experience: Autobiographies (London, 1963), 353, 350. 3. Isaiah Berlin, The Roots of Romanticism (London, [1965] 2000), 97. 4. For a useful discussion, see: Peter Ryley, Making Another World Possible: Anar- chism, Anti-capitalism and Ecology in Late 19th and Early 20th Century Britain (New York, 2013); Mark Bevir, The Making of British Socialism (Princeton, 2011), 256–277. 5. Martin A. Miller, Kropotkin (Chicago, 1976), 166–167; Rodney Barker, Political Ideas in Modern Britain (London, 1978), 42 passim. 6. H. Oliver, The International Anarchist Movement in Late Victorian London (London, 1983), 136; see also: 92, 132–137. For a discussion of the signifi- cance of the Congress, see: Davide Turcato, Making Sense of Anarchism: Errico Malatesta’s Experiments with Revolution (Basingstoke, 2012), 136–139. 7. W. Tcherkesoff, Let Us Be Just: (An Open Letter to Liebknecht) (London, 1896), 7. 8. The report offered short biographies of Francesco Merlino, Gustav Landauer, Louise Michel, Amilcare Cipriani, Augustin Hamon, Élisée Reclus, Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis, Bernard Lazare, and Peter Kropotkin. N.A., Full Report of the Proceedings of the International Workers’ Congress, London, July and August, 1896 (London, 1896), 67–72. 9. N.A., Full Report of the Proceedings, 21, 17. 10. Matthew S. Adams, ‘Herbert Read and the fluid memory of the First World War: Poetry, Prose, and Polemic’, Historical Research (2014), 1–22; Janet S.K. Watson, Fighting Different Wars: Experience, Memory, and the First World War in Britain (Cambridge, 2004), 226. -

Freedom Press Bookshop

F .~ 5 - - _. _ 4.‘ - _;_L],|._ii_-'- i S‘ »= .;"5"- 1 I". -kWorld Inequality: Origins and Perspectives of the World ZERZAN. J. Elements of Refusal (essays on power and System (ed I. Wallerstein) £4.50 domination) £5.95 it-A Year of Our Lives: Hatfield Main. a colliery in the great ZIESING. M. The Scarlet Q: Anarchy, Religion and I coal strike £2.40 the Cult of Science (illustrated). Includes essay on Northern Ireland. ‘No Statist Solutions’ £4.50 BOOKS IN STOCK 1991-92 Section 2: Other Titles FREEDOM PRESS has been for the past 100 years publishers FREEDOM Pnsss BOOKSHOP in Angel Alley and distributors of the alternative social and political press. 84b Whitechapel High Street, London E1 7QX. Tel: 071- As well as Freedom fortnightly (founded 1886) and the 247 9249. Open Monday to Friday 10.00am to 6.00pm, new quarterly journal The Raven (1987). Freedom Press Saturday 10.00am to 5.00pm. irThe Anarchist Reader (ed. Woodcock) £4.95 JOLL. James. The Anarchists (2nd edition) £9.95 are publishers of more some fifty titles dealing not only Underground Aldgate East (Whitechapel Art Gallery exit). AVRICH. Paul. KROPOTKIN. Peter. with the philosophy of anarchism but with its practical An American Anarchist (life of Voltairine de Cleyre) +£25.50 Memoirs of a Revolutionist (intro by Nicolas Buses 15, 25, 40 and 253 pass close by. Many other Anarchist Portraits +£17.95 Walter. illustrated) £8.95 application to the problems of modern society. Such titles routes serve Aldgate Bus Station (500 yards). The Haymarket Tragedy £6.25 Memoirs of a Revolutionist (abridged) £6.95 as Anarchists in the Spanish Revolution by José Peirats. -

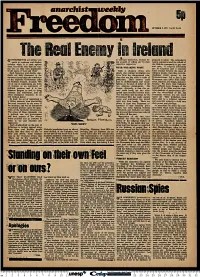

Standing on Their Own Feet Or on Ours?

anarchistmmweehly Vol 32 No 31 riOVERNMENTS are always very to extricate themselves, without be- prepared to admit. The campaign is quick to condemn and deplore ing accused of 'selling out' by their mainly centred around the refusal of ' violence when it is used against respective supporters. the Catholic community to pay rent them, but all the time they are wag- *2? and rates. If religious differences ing war on their own populations NEAR BREAKING POINT can be forgotten and a common in the name of 'Law and Order'. Such a situation shows \pry bond created between the mass of Such hypocrisy and double stan- clearly that nothing worthwhile can ordinary people, then this civil dis- dards are fully illustrated in the come from the compromised solu- obedience could spread to the statement issued after the conclusion tions that are the stock in trade of Protestant areas. Let us face it, the of the tripartite Government talks politicians. Their answers could Protestants also suffer from indig- on Northern Ireland. It reads: 'We lead to disillusionment and resent- nities, injustice, low wages, and poor are at one in condemning any form *SpV '■"■ t •■■■•.-•>a*-v.tv13fc:V-J~. ■ '. ¥r \£-\. ■':'<*.^^!.^/'Ui/^jKjp,-ki,f-^AJi^ fulness on the part of either of the . housing. We know that Catholics of violence as an instrument of il'*;(»»'>,i,^'lk"'f-l<*. -»fr''^ . Vt'/i'li'/-- 1 '' '*■ ■''■**4fflv- ■ ' V'^&f«Ufl*?tivr r two religious communities. The have suffered more because of the political pressure and it is our danger, obviously, is that this en- inability of the State and the capi- common purpose to seek to bring mity could break out into wide- talist methods of production to pro- violence and internment, and all spread open hostility between them. -

Anarchism and Religion

Anarchism and Religion Nicolas Walter 1991 For the present purpose, anarchism is defined as the political and social ideology which argues that human groups can and should exist without instituted authority, and especially as the historical anarchist movement of the past two hundred years; and religion is defined as the belief in the existence and significance of supernatural being(s), and especially as the prevailing Judaeo-Christian systemof the past two thousand years. My subject is the question: Is there a necessary connection between the two and, if so, what is it? The possible answers are as follows: there may be no connection, if beliefs about human society and the nature of the universe are quite independent; there may be a connection, if such beliefs are interdependent; and, if there is a connection, it may be either positive, if anarchism and religion reinforce each other, or negative, if anarchism and religion contradict each other. The general assumption is that there is a negative connection logical, because divine andhuman authority reflect each other; and psychological, because the rejection of human and divine authority, of political and religious orthodoxy, reflect each other. Thus the French Encyclopdie Anarchiste (1932) included an article on Atheism by Gustave Brocher: ‘An anarchist, who wants no all-powerful master on earth, no authoritarian government, must necessarily reject the idea of an omnipotent power to whom everything must be subjected; if he is consistent, he must declare himself an atheist.’ And the centenary issue of the British anarchist paper Freedom (October 1986) contained an article by Barbara Smoker (president of the National Secular Society) entitled ‘Anarchism implies Atheism’. -

Everywhere from Britain’S Rebel Music Revival to Anti-Colonial Conflict in Papua, It’S Not All Paralysis and Defeat Around Here

XXXX 1 vol 79:2 winter 2019/20 anarchist journal by donation KICKING OFF EVERYWHERE FROM BRITain’S REBEL MUSIC REVIVAL TO ANTI-COLONIAL CONFLICT IN PAPUa, it’S NOT All PARALYSIS AND DEFEAT AROUND HERE Pic by Anzi Matta | pateron.com/anzimatta PLUS: M THE HOUSING CRISIS n RISE OF DOMESTIC MURDER aberdeen’S RADICAL SPACE @ BISEXUAL ACTIVISM IN LONDON 2 editorial It all just needs a spark. From Chile to and token giveaways, somehow manages some common denominator with us. Start Hong Kong, through Catalonia to France to contain it? Will it be the far-right with building structures based on the principle — it has been kicking off everywhere. their populist policies? Or will these of mutual aid: show how this can work in What these events have in common is that upheavals lead to long-lasting, positive practice. Share our knowledge of what they were all sparked by a government and revolutionary changes to the world the State is, and what its main principles decision, of lesser or greater significance, we all live in, the sort of changes we will are. Join in with local struggles. Show but in all cases the States which did so be happy to support? that anarchism, while it maintains a solid thought they could get away with it, as In the UK one may, perhaps reputation of utopianism, can be and is they have done for decades until now. optimistically, assume that with almost the answer to the world-wide problems These decisions have been inflicted on a decade of the Tory rule behind us that we are all facing. -

Changing Anarchism.Pdf

Changing anarchism Changing anarchism Anarchist theory and practice in a global age edited by Jonathan Purkis and James Bowen Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Copyright © Manchester University Press 2004 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective authors. This electronic version has been made freely available under a Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC- ND) licence, which permits non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction provided the author(s) and Manchester University Press are fully cited and no modifications or adaptations are made. Details of the licence can be viewed at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 6694 8 hardback First published 2004 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset in Sabon with Gill Sans display by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Manchester Printed in Great Britain by CPI, Bath Dedicated to the memory of John Moore, who died suddenly while this book was in production. His lively, innovative and pioneering contributions to anarchist theory and practice will be greatly missed. -

Damned Fools in Utopia and Other Writings on Anarchism and War Resistance Nicholas Walter Nicolas Walter Was the Son of the Neurologist, W

daMNED Fools IN utoPIA and Other Writings on Anarchism and War Resistance Nicholas Walter Nicolas Walter was the son of the neurologist, W. Grey Walter, and both his grandfathers had known Peter Kropotkin and Edward Carpenter. However, it was the twin jolts of Suez and the Hungarian Revolution while still a student, followed by participation in the resulting New Left and nuclear disarmament movement, that led him to anarchism himself. His personal history is recounted in two autobiographical pieces in this collection as well as the editor’s introduction. During the 1960s he was a militant in the British nuclear disarmament movement – especially its direct-action wing, the Committee of 100 – he was one of the Spies of Peace (who revealed the State’s preparations for the governance of Britain after a nuclear war), he was close to the innovative Solidarity Group and was a participant in the homelessness agitation. Concurrently with his impressive activism he was analyzing acutely and lucidly the history, practice and theory of these intertwined movements; and it is such writings – including Non-violent Resistance and The Spies for Peace and After – that form the core of this book. But there are also memorable pieces on various libertarians, including the writers George SUBJECT CATEGORY Orwell, Herbert Read and Alan Sillitoe, the publisher C.W. Daniel and POLITICS/ the maverick Guy A. Aldred. The Right to be Wrong is a notable polemic against laws limiting the freedom of expression. Other than anarchism, historY the passion of Walter’s intellectual life was the dual cause of atheism and rationalism; and the selection concludes appropriately with a fine essay PRICE on Anarchism and Religion and his moving reflections, Facing Death.