The Game Design Sequence Chapter Five

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ART of COMPUTER GAME DESIGN Digitized by the Internet Archive

THEARTOF COMPUTER GAME fll7€2V^TU REFLECTIONS OF MFlji^Mtli^ A MASTER GAME DESIGNER Chris Crawford I THE ART OF COMPUTER GAME DESIGN Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/artofcomputergamOOchri THE ART OF COMPUTER GAME DESIGN Chris Crawford Osborne/McGraw-Hill Berkeley, California Published by Osborne/McGraw-Hill 2600 Tenth Street Berkeley, California 94710 U.S.A. For information on translations and book distributors outside of the U.S.A., please write to Osborne/McGraw-Hill at the above address. THE ART OF COMPUTER GAME DESIGN Copyright ® 1984 by McGraw-Hill. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act of 1976. no part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a data base or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher, with the exception that the program listings may be entered, stored, and executed in a computer system, but they may not be reproduced for publication. 1234567890 DODO 89876543 ISBN 0-88134-117-7 Judy Ziajka, Acquisitions Editor Paul Jensen, Technical Editor Richard Sanford, Copy Editor Judy Wohlfrom, Text Design Yashi Okita, Cover Design TRADEMARKS The capitalized trademarks are held by the following alphabetically listed companies: PREPPIE! Adventure International TEMPEST Atari, Inc. MISSILE COMMAND RED BARON PONG STAR RAIDERS SPACE WAR ASTEROIDS CENTIPEDE BATTLEZONE CAVERNS OF MARS YAR'S REVENGE MAZE CRAZE DODGE 'EM BREAKOUT SUPERBREAKOUT CIRCUS ATARI WARLORDS AVALANCHE NIGHT DRIVER SUPERMAN HAUNTED HOUSE EASTERN FRONT 1941 SCRAM ENERGY CZAR COMBAT EXCALIBUR ADVENTURE CRUSH. -

Atari Turned Into a Computer Manufacturer

Under the management of media group Warner, Atari turned into a computer manufacturer. Four joystick ports, two cartridge slots, great graphics and sound made Atari computers the best games machines of the early 1980s. Atari USA, 1979 800 Units sold: Unknown Number of games: 1,000 Game storage: Cartridge, Disk, Tape Games developed until: 1990 From 1972, Nolan Bushnell’s Pong arcade machines With two cartridge slots, four joystick ports and a cus- and consoles paved the way for a global market of tom circuitry focused on graphics and animation, the The forces of light vs. darkness: in the action-strategy hybrid The Atari 400 was the small and electronic games. Within the entertainment industry his Atari 800 shone as the perfect games machine in 1979. Archon (1983), fantasy chess pieces battle it out in real-time. cheap alternative to its big brother Atari 800. company quickly became the hottest thing since sliced Arcade conversions made up a good portion of the bread. In 1976, prior to the release of the Atari VCS early software, but at the same time, games exclusively In 1982, Bill Stealey and Sid Meier launched Micro- The team conceived a hardware concept that was revo- 2600 console, media giant Warner gobbled up Atari, developed for the 800 appeared. Doug Neubauer’s prose to produce and sell Atari games. Other lutionary at the time. Three custom chips supported the pumping it with millions of dollars for the next step in 3D space odyssey Star Raiders lit the development star designers of the 8-bit era were Paul Edel- 6502 CPU: the Alphanumeric Television Interface Circuit the process: Atari’s goal was to conquer the nascent scene's fire. -

The Art of Computer Game Design the Art of Computer Game Design by Chris Crawford

The Art of Computer Game Design The Art of Computer Game Design by Chris Crawford Preface to the Electronic Version: This text was originally composed by computer game designer Chris Crawford in 1982. When searching for literature on the nature of gaming and its relationship to narrative in 1997, Prof. Sue Peabody learned of The Art of Computer Game Design, which was then long out of print. Prof. Peabody requested Mr. Crawford's permission to publish an electronic version of the text on the World Wide Web so that it would be available to her students and to others interested in game design. Washington State University Vancouver generously made resources available to hire graphic artist Donna Loper to produce this electronic version. WSUV currently houses and maintains the site. Correspondance regarding this site should be addressed to Prof. Sue Peabody, Department of History, Washington State University Vancouver, [email protected]. If you are interested in more recent writings by Chris Crawford, see the "Reflections" interview at the end of The Art of Computer Game Design. Also, visit Chris Crawford's webpage, Erasmatazz. An acrobat version of this text is mirrored at this site: Acrobat Table of Contents ■ Acknowledgement ■ Preface ■ Chapter 1 - What is a Game? ■ Chapter 2 - Why Do People Play Games? ■ Chapter 3 - A Taxonomy of Computer Games ■ Chapter 4 - The Computer as a Game Technology ■ Chapter 5 - The Game Design Sequence ■ Chapter 6 - Design Techniques and Ideals ■ Chapter 7 - The Future of Computer Games ■ Chapter 8 - Development of Excalibur ■ Reflections - Interview with Chris WSUV Home Page | Prof. -

Wargame, Strategy, Action, and Multiplayer in the Early 1980S1

Special Issue The Rise(s) and Fall(s) of Video Game Genres May 2019 74-102 Wargame, Strategy, Action, and Multiplayer in the Early 1980s1 Simon Dor Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue Abstract: Extensive literature underlines the importance to critically examine the phenomenon of game classification. In computer games magazines of the 1980 decade, the combination of “action”, “arcade,” or “real-time” with “strategy” is quite common. Here and there, the expression “real-time strategy” is used. But real-time strategy games as we will come to know them in the 1990s are not very similar to games labelled “real-time strategy” in the 1980s: we are simply not witnessing the description of the same gameplay or experience. Micro-histories of gameplay can underline different forms of continuities and reveal new perspectives on strategy gaming. Keywords: Game genres; real-time strategy; strategy games; 1980 decade; history of games. Résumé en français à la fin de l’article ***** 1 I have to thank the LUDOV research team from Université de Montréal where I pursued my doctoral research for some of the findings used here. I also want to note that I would have loved to play each game mentioned here, but it is unfortunately in practice impossible; I hope the observations I make here will be corroborated or refuted by first-hand play when some of these games will be found or made available. Wargame, Strategy, Action, and Multiplayer in the Early 1980s To poorly paraphrase a maxim, the history of games was written by its great successes. … a discussion of real-time strategy games invariably conjures up visions of Dune 2, Command & Conquer, and Warcraft. -

Playing Games in Education - Or, Thank You Mario… but Our Princess Is in Another University!

Playing Games in Education - or, Thank You Mario… But Our Princess Is In Another University! Ruben R. Puentedura, Ph.D. Our Topics for this Morning… What is a (Good) Videogame? Elements of Game Design and Construction Videogames and Education What is a (Good) Videogame? Zeroth-Order Readings Huizinga, Homo Ludens Salen & Zimmerman, Rules of Play Formal Definitions of Play and Game (Salen & Zimmerman) "Play is free movement within a more rigid structure." "A game is a system in which players engage in an artificial conflict, defined by rules, that results in a quantifiable outcome." Salen, K. and E. Zimmerman, Rules of Play : Game Design Fundamentals. The MIT Press. (2003) Relationship of Videogame Play to General Play Videogames Game Play Ludic Activities Being Playful Game as Radial Category Goal-Driven More Narrative The Sims Grand Theft Auto Pong Abstraction Videogame Simulation Second Life Tetris Less Narrative Arbitrary Genres of Videogames 1 - Action Shoot 'Em Ups (Space Invaders … Ikaruga) Platformers (Donkey Kong … Super Mario Sunshine) First-person Shooters (Doom … Half-Life 2) Sports Games (Pong … World Soccer Winning Eleven 8 International) Genres of Videogames 2 - Narrative Interactive Fiction (Adventure … Curses) Graphic Adventures (King's Quest … Myst series … Grim Fandango) Action Adventures (Atari Adventure … Zelda series) Role-Playing-Games (Wizardry … Neverwinter Nights … Final Fantasy Series) MMORPGs (MUDs, MOOs, MUSHs … World of Warcraft) Genres of Videogames 3 - Simulation Sims (SimCity … The Sims) Turn-based Strategy Games -

The German Blitzkrieg Against the USSR, 1941

BELFER CENTER PAPER The German Blitzkrieg Against the USSR, 1941 Andrei A. Kokoshin PAPER JUNE 2016 Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.belfercenter.org Design & Layout by Andrew Facini Cover image: A German map showing the operation of the German “Einsatzgruppen” of the SS in the Soviet Union in 1941. (“Memnon335bc” / CC BY-SA 3.0) Statements and views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author and do not imply endorsement by Harvard University, Harvard Kennedy School, or the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Copyright 2016, President and Fellows of Harvard College Printed in the United States of America BELFER CENTER PAPER The German Blitzkrieg Against the USSR, 1941 Andrei A. Kokoshin PAPER JUNE 2016 About the Author Andrei Kokoshin is a member of the Russian Academy of Sciences and dean of Moscow State University’s Faculty of World Politics. He has served as Russia’s first deputy defense minister, secretary of the Defense Council and secretary of the Security Council. Dr. Kokoshin has also served as chairman of the State Duma’s Committee on the CIS and as first deputy chairman of the Duma’s Committee on Science and High Technology. Table of Contents Abstract ....................................................................................vi Introduction .............................................................................. 1 Ideology, Political Goals and Military Strategy of Blitzkrieg in 1941 ..................................................................3 -

Dismantling the Myths of the Eastern Front: the Role of the Wehrmact in the War of Annihilation Andrew Kapinos, Virginia Tech

Dismantling the Myths of the eastern Front: The Role of the Wehrmact in the War of Annihilation Andrew Kapinos, Virginia Tech he English-language historiography of the Eastern Front of World War II is notably sparse until the late 1980s and early 1990s. In the Tfirst couple of post-war decades, memoirs written by former generals in the Wehrmacht, the armed forces of the Third Reich, dominated the historical conversation. These memoirs created the myth of the clean and apolitical Wehrmacht, where military operations and genocidal policy were separate. According to this narrative, it was the Nazi leadership and the SS that committed large-scale atrocities on the Eastern Front while the Wehrmacht focused only on winning the war. Anglo-American historians largely accepted these accounts, mainly because of Cold War tensions with the Soviet Union. The experiences of German generals were invaluable insights into Soviet doctrine, and therefore the generals’ tendency to downplay their own complicity in Nazi war crimes was largely accepted. Increasing access to German and later Soviet archives in the 1980s and 1990s revealed that this was far from the truth. Recent historical works have demonstrated that genocidal policy and war strategy were inextricably linked. The question of why the Wehrmacht accepted Nazi ideology is more difficult to answer. Historians have applied this question to both the High Command and to the everyday soldiers, with differing conclusions. The war on the Eastern Front started with the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, codenamed Operation Barbarossa, in June 1941. The Nazis enjoyed early success, pushing deep into Soviet territory throughout the summer. -

Theescapist 012.Pdf

I have a secret. You know all the times who also enjoyed videogames. Upon Since then, I have plunged back into the I’ve mentioned my NES? Well, it’s not hitting this critical mass of two gaming pool, owning my very own because I’m some minimalist, older is previously-avid-gamers, each lacking a Playstation 2 and playing the occasional To the Editor: There appears to be a inherently better, classic-game-o-phile. gaming console, we decided we should Xbox and PC game. But how many mistake in the article “Don’t Ever Take procure a Playstation 2. Excited to get others out there stuck a toe into the pool Sides Against The Corps Again” (Issue The truth of it is, I “stepped away from back into a pastime I looked back on and came away, never to return? #10), by Mark Wallace. Mr. Wallace gaming” for a few years. Between the with fondness, I researched titles, talked interprets a study by PlayOn as finding lack of desire to shell out another few to Electronics Boutique clerks and found Gamers and designers alike have felt that in WoW, players that belong to hundred dollars for a SNES by my a game I was pretty sure I would like. I disenfranchised in one way or another by guilds level faster on average than parents (and me, as I didn’t have that was set. the unforgiving march of Time. And that players who don’t. Looking at this study, kind of cash) and my difficult workload in is what this issue of The Escapist is it appears that the results are quite the high school and the university, I just Then a strange thing happened. -

Fifth Annual Games for Change Festival at Parsons the New School for Design New York, NY

Fifth Annual Games for Change Festival at Parsons The New School for Design New York, NY June 2-4, 2008 Fifth Annual Games for Change Festival June 2-4 2008 Proudly Sponsored by 1 G4CFESTIVAL June 2-4, 2008 Festival Background Welcome to the fifth annual Games New School, we launched PETLab— for Change Festival! This year’s a public interest game design and festival brings together innovators research lab for interactive media A game for change from the game industry, education, Prototyping, Evaluation, Teaching, government, philanthropy, and non- and Learning. We continued working is a digital game profit sector to explore how games with our Microsoft partners during which engages a can change our lives and our world. the year on the Xbox 360 Games for contemporary social Our panels include many of the Change Challenge, whose winners leading thinkers in social issue game will be selected next month. We also issue to foster a design, research, and practice, as well worked closely with the more equitable, just as leaders in related fields. This year Entertainment Consumers and/or tolerant we have added to the festival a day- Association and the Save the Internet society. long workshop on the fundamentals Coalition on the net neutrality of social issue games specifically to initiative. Our social issues games list assist the many nonprofit and regional Games for Change organizations new to digital games. chapters continued providing lively The New School for all the support We are also proud to host another forums on a broad range of social they provide in putting on this Festival Expo Night featuring some of issue game topics. -

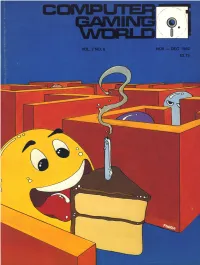

Computer Gaming World Issue

VOL. 2 NO. 6 Nov. - Dec. - 1982 From the Editor... Features This issue marks one year that COMPUTER GAMING WORLD has been in existence. On the cover of this THE HISTORY OF A WARGAME DESIGN 11 issue we take time to do a little From Idea to Royalties Gary Grigsby celebrating and enjoy a piece of birthday cake. The past year has been JAPANESE STRATEGY IN dangerous, tense, and challenging. But GUADALCANAL CAMPAIGN 18 most of all, it has been rewarding. The response of our readers and the industry How to win with the Japanese Stephen Van Osdell in general are the "power pills - that have kept us going when the "ghosts" of FOUR FOR THE ATARI 20 problems have attacked us. Four Games Reviewed Allen Doum Each issue has increased quality and added features. This issue is no EASTERN FRONT: Scenario Options 22 exception. In addition to new layout features, we have added another new Historical modifications you can make Ian Chadwick column, MICROCOMPUTER MATHE- MAGIC By Dr. Michael Ecker. Look for a STAR MAZE 26 regular Atari 400/800 column beginning Review and CONTEST Russell Sipe in our next issue. Look for the STAR MAZE contest in this issue. LEGIONNAIRE: Review and Analysis 27 Chris Crawford's New Game Bill Willett CYTRON MASTERS FOR ATARI 31 Conversion Versus Upgrade Dan Bunten ANDROMEDA CONQUEST 34 Strategies and Rules Modifications Floyd Mathews BUNGO PETE and the WONDER BEAR 36 Two New Scenarios For TORPEDO FIRE Bob Proctor BEYOND SARGON II 39 Scenarios For Chess Roger J. Cooper Departments Inside the Industry 2 Letters 3 Taking a peek 4 Hobby and Industry News 10 The Silicon Cerebrum 14 Real World Gaming 16 Microcomputer Mathemagic 23 Route 80 (TRS-80) 33 Micro-Reviews 41 Writing For CGW 46 Reader Input Device 47 INSIDE THE INDUSTRY by Dana Lombardy, Associate Publisher Game Merchandising Last time we looked at the top sellers as reported by 105 It should be noted that this chart does not rate the game and educational software manufacturers. -

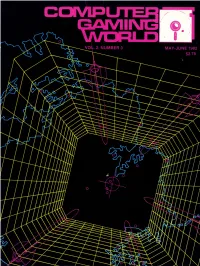

Computer Gaming World Issue

- _ VOL. 2 NO. 3 MAY - JUNE 1982 Features WIZARDRY: PROVING GROUNDS... 6 Review of Sir-tech's popular fantasy game Mark Marlow A BEGINNER'S GUIDE TO STRATEGY AND 10 TACTICS IN EASTERN FRONT Bob Proctor TIME ZONE: AN INTERVIEW WITH ROBERTA WILLIANIS 14 VOYAGER I: SABOTAGE OF THE ROBOT SHIP 16 Avalon Hill's new game reviewed Dave Jones SOME SCENES FROM THE 7TH WEST COAST COMPUTER FAIRE 20 LONG DISTANCE GAMING: GAMES VIA 22 THE SOURCE AND COMPUSERVE Deirdre Maloy JABBERTALICY, IN DEPTH 26 Automated Simulation's word game reviewed Marty Halpern GREATEST BASEBALL TEAM - RESULTS 30 OLYMPIC DECATHLON: A CLASSIC COMPUTER GAME 32 Muse's popular game analyzed Russell Sipe THE EAGLE HAS LANDED: A TRS-80 REVIEW 34 Adventure International's Lunar Lander game reviewed Richard McGrath SWASHBUCKLER: ANOTHER KIND OF PIRACY 36 A new game from DataMost Michael Cranford Departments Letters 2 Hobby & Industry Notes 4 Initial Comments 4 Atari Arcade 18 Silicon Cerebrum 24 Writing for Computer Gaming World 39 Reader Input Device 40 is against its objective and how well players of Cartels are aware of this LETTERS it is met. In several places on the reasoning, the vast majority found packaging and in the game manual that the animated interlude made FROM "CARTEL" AUTHOR Cartels states its goal to be a play- the game "feel better". A reviewer able game built on a foundation of a could very well miss the subtlety of very realistic business simulation. this element, but one not so obsessed Dear Editor: If we look only at those sections of with "delays" might have at least A magazine that deals exclusively your review that deal with this issue not wasted a whole paragraph on a with the field of computer games is such points as follow are made: point that in no way reduces the an idea whose time has come! As a "well executed economic simula- game's overall fitness as a playable, computer games designer (I have tion", "quite good...market simula- realistic business simulation. -

Chris Crawford on Interactive Storytelling SECOND EDITION Chris Crawford on Interactive Storytelling, Second Edition Chris Crawford

chris crawford on interactive storytelling SECOND EDITION Chris Crawford on Interactive Storytelling, Second Edition Chris Crawford New Riders www.newriders.com To report errors, please send a note to [email protected] New Riders is an imprint of Peachpit, a division of Pearson Education. Copyright © 2013 Chris Crawford Senior Editor: Karyn Johnson Development Editor: Robyn Thomas Production Editor: Cory Borman Technical Editor: Michael F. Lynch, Ph.D. Copyeditor: Kelly Kordes Anton Proofreader: Scout Festa Composition: Danielle Foster Indexer: Jack Lewis Cover design: Aren Howell Notice of Rights All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For information on getting permission for reprints and excerpts, contact [email protected]. Notice of Liability The information in this book is distributed on an “As Is” basis, without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of the book, neither the author nor Peachpit shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the instructions contained in this book or by the computer software and hardware products described in it. Trademarks Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Peachpit was aware of a trademark claim, the designations appear as requested by the owner of the trademark. All other product names and services identified throughout this book are used in editorial fashion only and for the benefit of such companies with no intention of infringement of the trademark.