Wargame, Strategy, Action, and Multiplayer in the Early 1980S1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ssi-87-88Catalog

NEW GAMES NEW GAMES In the 21st century, Europe suffered the same bio-war that devas PANZER STRIKE!'" boasts the highest resolution of any of our World tated America, a holocaust that established the deadly scenario for War 11 titles. Each unit symbol represents either one tank/gun or a squad SSl 's exciting ROADWAR 2000 ".' of infantry; each square of the 60 x60 map, 50 yards. The action is so Now this sequel creates a post-doomsday Europe held hostage detailed, you 'll feel like you 're caught in the middle of the blitzkrieg of by maniacal terrorists who are threatening the German Army in all its major campaigns . to detonate five nuclear devices across the Three theaters are covered: The entire continent. Before the United Nations caves Eastern Front, the Western Front in 1940, in to their demands, it has agreed to a last and the North African campaign. This tactical desperate measure - send in the one man game includes practically every ground who can save Europe: You . weapon used in those theaters - from ROADWAR EUROPA starts off with tanks, tank destroyers and artillery to trucks, llU APPLE (Dec.) APPLE (low) you as the leader of a large road gang mortars and machine guns. C·H/128 (low) equipped with cars, trucks, and motorcycles C·H/128 (Jan.) AlllGA (low) Advanced . The ratings for armored vehicles go IBM (Nov.) of your own design. Transfer your crew from beyond even our usual high standards for ATARI ST (low) ROADWAR 2000 or create a new elite band. realism. For example, armor is segmented Introductory. -

October 1998

OCTOBER 1998 GAME DEVELOPER MAGAZINE V GAME PLAN It’s First and Goal for EDITOR IN CHIEF Alex Dunne [email protected] MANAGING EDITOR Tor D. Berg [email protected] Fantasy Sports DEPARTMENTS EDITOR Wesley Hall whall@mfi.com his fall, as the leaves turn success stories. Unlike the traditional ART DIRECTOR Laura Pool lpool@mfi.com shades of orange and the days studio’s royalty revenue model, SWS has EDITOR-AT-LARGE Chris Hecker grow shorter, one of the two revenue streams: a two-year licens- [email protected] largest, most massively multi- ing agreement to develop more than 40 CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Jeff Lander T [email protected] player games picks up steam and sucks online games for CNN/SI (http://base- in participants. It’s a role-playing game ball.cnnsi.com), plus revenue from ban- Mel Guymon [email protected] that draws tens of thousands (gads, ner advertising displayed on the CNN/SI Omid Rahmat probably more) of players, and if my game’s web pages, which garner 50 mil- [email protected] predictions are right, it will be one of lion page views per month. Surprisingly, ADVISORY BOARD Hal Barwood the most popular attractions on the and in contrast to most commercial fan- Noah Falstein eventual TV set-top box. I’m talking tasy leagues, some of the CNN/SI Brian Hook about fantasy football leagues. leagues are free for participants and Susan Lee-Merrow It’s taken quite a bit of time for me to offer cash prizes for winners. These are Mark Miller 2 accept the fact that fantasy league sports the guppy leagues which, hopefully, (there are also fantasy leagues for base- entice the most enthusiastic players to COVER IMAGE Epic MegaGames ball, hockey, and perhaps even pro join the premiere leagues for $15. -

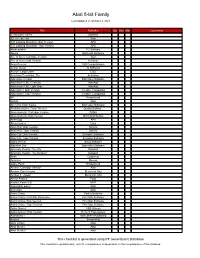

Atari 8-Bit Family

Atari 8-bit Family Last Updated on October 2, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 221B Baker Street Datasoft 3D Tic-Tac-Toe Atari 747 Landing Simulator: Disk Version APX 747 Landing Simulator: Tape Version APX Abracadabra TG Software Abuse Softsmith Software Ace of Aces: Cartridge Version Atari Ace of Aces: Disk Version Accolade Acey-Deucey L&S Computerware Action Quest JV Software Action!: Large Label OSS Activision Decathlon, The Activision Adventure Creator Spinnaker Software Adventure II XE: Charcoal AtariAge Adventure II XE: Light Gray AtariAge Adventure!: Disk Version Creative Computing Adventure!: Tape Version Creative Computing AE Broderbund Airball Atari Alf in the Color Caves Spinnaker Software Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves Quality Software Alien Ambush: Cartridge Version DANA Alien Ambush: Disk Version Micro Distributors Alien Egg APX Alien Garden Epyx Alien Hell: Disk Version Syncro Alien Hell: Tape Version Syncro Alley Cat: Disk Version Synapse Software Alley Cat: Tape Version Synapse Software Alpha Shield Sirius Software Alphabet Zoo Spinnaker Software Alternate Reality: The City Datasoft Alternate Reality: The Dungeon Datasoft Ankh Datamost Anteater Romox Apple Panic Broderbund Archon: Cartridge Version Atari Archon: Disk Version Electronic Arts Archon II - Adept Electronic Arts Armor Assault Epyx Assault Force 3-D MPP Assembler Editor Atari Asteroids Atari Astro Chase Parker Brothers Astro Chase: First Star Rerelease First Star Software Astro Chase: Disk Version First Star Software Astro Chase: Tape Version First Star Software Astro-Grover CBS Games Astro-Grover: Disk Version Hi-Tech Expressions Astronomy I Main Street Publishing Asylum ScreenPlay Atari LOGO Atari Atari Music I Atari Atari Music II Atari This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Computer Gaming World Issue

VOL. 2 NO. 2 MAR. - APR. 1982 Features SOUTHERN COMMAND 6 Review of SSI's Yom Kippur Wargame Bob Proctor SO YOU WANT TO WRITE A COMPUTER GAME 10 Advice on Game Designing Chris Crawford NAPOLEON'S CAMPAIGNS 1813 & 1815: SOME NOTES 12 Player's, Designer's, and Strategy Notes Joie Billings SO YOU WANT TO WIN A MILLION 16 Analysis of Hayden's Blackjack Master Richard McGrath ESCAPE FROM WOLFENSTEIN 18 Short Stay Based on the Popular Game Ed Curtis ODE TO JOY, PADDLE AND PORT: 19 Some Components for Game Playing Luther Shaw THE CURRENT STATE OF 21 COMPUTER GAME DOCUMENTATION Steve Rasnic Tern NORDEN+, ROBOT KILLER 25 Winner of CGW's Robotwar Tournament Richard Fowell TIGERS IN THE SNOW: A REVIEW 30 Richard Charles Karr YOU TOO CAN BE AN ACE 32 Ground School for the A2-FS1 Flight Simulator Bob Proctor BUG ATTACK: A REVIEW 34 Cavalier's New Arcade Game Analyzed Dave Jones PINBALL MANIA 35 Review of David's Midnight Magic Stanley Greenlaw Departments From the Editor 2 Hobby & Industry News 2 Initial Comments 3 Letters 3 The Silicon Cerebrum 27 Micro Reviews 36 Reader's Input Device 40 From the Editor... Each issue of CGW brings the magazine closer Input Device". Not only will it help us to know just to the format we plan to achieve. This issue (our what you want to read, it will also let the man- third) is expanded to forty pages. Future issues ufacturers know just what you think about the will be larger still. games on the market. -

Strategic Simulations, Inc;' · Credits Table of Contents

STRATEGIC SIMULATIONS, INC;' · CREDITS TABLE OF CONTENTS Qame Creation: Beyond Software, Inc. Introduction: First Night in Yartar ......... ,................................ ,........................... ......... 1 System Creation: SSI Special Projects Qroup Important Features of the Savage Frontier .................................................................. 2 Scenario Design: Don Daglow Towns and Cities .................................................................................................... 2 IBM Programming and Forests ..................................................................................................................... 3 Technical Design: Cathryn Mataga The Troll moors .............................................................................. ... ....................... 3 Amiga Programming: Linwood Taylor C-64 Programming: Mark Manyen The Cjreat Desert .............. ·....................................................................................... 3 Other C-64 Programming: Westwood Associates lslands ..................................................................................................................... 3 Amiga Programming Support and Characters and Parties ....................................................... .. ........................ ... ............. 4 IBM Music Driver: MicroMagic, Inc. Player Races ............................................................................................................ 4 IBM Sound Effects Driver: John Ratcliffe Ability Scores ................................................................................................ -

THE ART of COMPUTER GAME DESIGN Digitized by the Internet Archive

THEARTOF COMPUTER GAME fll7€2V^TU REFLECTIONS OF MFlji^Mtli^ A MASTER GAME DESIGNER Chris Crawford I THE ART OF COMPUTER GAME DESIGN Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/artofcomputergamOOchri THE ART OF COMPUTER GAME DESIGN Chris Crawford Osborne/McGraw-Hill Berkeley, California Published by Osborne/McGraw-Hill 2600 Tenth Street Berkeley, California 94710 U.S.A. For information on translations and book distributors outside of the U.S.A., please write to Osborne/McGraw-Hill at the above address. THE ART OF COMPUTER GAME DESIGN Copyright ® 1984 by McGraw-Hill. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act of 1976. no part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a data base or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher, with the exception that the program listings may be entered, stored, and executed in a computer system, but they may not be reproduced for publication. 1234567890 DODO 89876543 ISBN 0-88134-117-7 Judy Ziajka, Acquisitions Editor Paul Jensen, Technical Editor Richard Sanford, Copy Editor Judy Wohlfrom, Text Design Yashi Okita, Cover Design TRADEMARKS The capitalized trademarks are held by the following alphabetically listed companies: PREPPIE! Adventure International TEMPEST Atari, Inc. MISSILE COMMAND RED BARON PONG STAR RAIDERS SPACE WAR ASTEROIDS CENTIPEDE BATTLEZONE CAVERNS OF MARS YAR'S REVENGE MAZE CRAZE DODGE 'EM BREAKOUT SUPERBREAKOUT CIRCUS ATARI WARLORDS AVALANCHE NIGHT DRIVER SUPERMAN HAUNTED HOUSE EASTERN FRONT 1941 SCRAM ENERGY CZAR COMBAT EXCALIBUR ADVENTURE CRUSH. -

Disruptive Innovation and Internationalization Strategies: the Case of the Videogame Industry Par Shoma Patnaik

HEC MONTRÉAL Disruptive Innovation and Internationalization Strategies: The Case of the Videogame Industry par Shoma Patnaik Sciences de la gestion (Option International Business) Mémoire présenté en vue de l’obtention du grade de maîtrise ès sciences en gestion (M. Sc.) Décembre 2017 © Shoma Patnaik, 2017 Résumé Ce mémoire a pour objectif une analyse des deux tendances très pertinentes dans le milieu du commerce d'aujourd'hui – l'innovation de rupture et l'internationalisation. L'innovation de rupture (en anglais, « disruptive innovation ») est particulièrement devenue un mot à la mode. Cependant, cela n'est pas assez étudié dans la recherche académique, surtout dans le contexte des affaires internationales. De plus, la théorie de l'innovation de rupture est fréquemment incomprise et mal-appliquée. Ce mémoire vise donc à combler ces lacunes, non seulement en examinant en détail la théorie de l'innovation de rupture, ses antécédents théoriques et ses liens avec l'internationalisation, mais en outre, en situant l'étude dans l'industrie des jeux vidéo, il découvre de nouvelles tendances industrielles et pratiques en examinant le mouvement ascendant des jeux mobiles et jeux en lignes. Le mémoire commence par un dessein des liens entre l'innovation de rupture et l'internationalisation, sur le fondement que la recherche de nouveaux débouchés est un élément critique dans la théorie de l'innovation de rupture. En formulant des propositions tirées de la littérature académique, je postule que les entreprises « disruptives » auront une vitesse d'internationalisation plus élevée que celle des entreprises traditionnelles. De plus, elles auront plus de facilité à franchir l'obstacle de la distance entre des marchés et pénétreront dans des domaines inconnus et inexploités. -

Advanced Practical Necromancy

1 Episode 2 Part 2: Advanced Practical Necromancy Some games are dead or dying.1 *horror scream* But, we can still save many of them or bring back others to life. So get your Phoenix Downs or start casting your resurrection spells. *intro fade in song* Let’s go! *intro fade out* Hello and welcome to Deadplay, a podcast on videogame preservation and analysis! My name is Dany Guay-Belanger, and I’ll be your host. Last time, we talked about zombie games, and about Joust and SCOG. Today, we talk about the future of videogame reanimation through what historians call ‘oral history’, as well as Let’s Plays and emulation. When I went to the Strong Museum of Play, I discovered so much information about Joust and SCOG. But the reason why I mentioned everything, apart from the fact that I was being an overexcited dork, wasn’t clear. Think back to when I was talking about some zombies being closer to the human they were before their death. If you have a truly mindless zombie, there’s only so much we can use to figure out who they were. Imagine a zombie apocalypse scenario and a biker who’s been bitten by a zombie crashes because he’s turning into a zombie. Say that zombie biker is stuck under their motorcycle and you happen to walk by it. You might be able to tell something about who that zombie was by looking at its clothes, its boots, or the motorcycle. You could also get much more information if you could get a hold of their wallet or the motorcycle’s registration papers. -

FORNAX #18 Commemorating the 75Th Anniversary of the Battle of the Coral Sea

FORNAX #18 Commemorating the 75th Anniversary of the Battle of the Coral Sea Fornax is a fanzine devoted to history, science fiction & gaming as well as other areas where the editor's curiosity goes. It is edited/published by Charles Rector. In the grand tradition of fanzines, it is mostly written by the editor. This is issue #18 published May 2017 If you want to write for Fornax, please send email submissions to crectorATmywayDOTcom, with a maximum length of 20,000 words. The same length requirement applies to fiction submissions as well. No poetry or artwork please. Any text format is fine. The same goes if you want to submit your work in the form of text in the email or as an attachment. There is no payment other than the exposure that you will get as a writer. Of course, Letters of Comment are always welcome. Material not written or produced by the Editor/Publisher is printed by permission of the various writers and artists and is copyright by them and remains their sole property and reverts to them after publication. If you want to read more by the editor/publisher, then point your browser to: http://omgn.com/blog/cjrector A Matter of Feedback One of the worst problems that I have been encountering while editing and publishing Fornax during the past two years is the lack of feedback from readers in the form of Letters Of Comment. In the typical issue of this fanzine, there are only three or so LOC’s. What all this means is that I feel like I’m flying blind in producing a fanzine for you the reader. -

Atari Turned Into a Computer Manufacturer

Under the management of media group Warner, Atari turned into a computer manufacturer. Four joystick ports, two cartridge slots, great graphics and sound made Atari computers the best games machines of the early 1980s. Atari USA, 1979 800 Units sold: Unknown Number of games: 1,000 Game storage: Cartridge, Disk, Tape Games developed until: 1990 From 1972, Nolan Bushnell’s Pong arcade machines With two cartridge slots, four joystick ports and a cus- and consoles paved the way for a global market of tom circuitry focused on graphics and animation, the The forces of light vs. darkness: in the action-strategy hybrid The Atari 400 was the small and electronic games. Within the entertainment industry his Atari 800 shone as the perfect games machine in 1979. Archon (1983), fantasy chess pieces battle it out in real-time. cheap alternative to its big brother Atari 800. company quickly became the hottest thing since sliced Arcade conversions made up a good portion of the bread. In 1976, prior to the release of the Atari VCS early software, but at the same time, games exclusively In 1982, Bill Stealey and Sid Meier launched Micro- The team conceived a hardware concept that was revo- 2600 console, media giant Warner gobbled up Atari, developed for the 800 appeared. Doug Neubauer’s prose to produce and sell Atari games. Other lutionary at the time. Three custom chips supported the pumping it with millions of dollars for the next step in 3D space odyssey Star Raiders lit the development star designers of the 8-bit era were Paul Edel- 6502 CPU: the Alphanumeric Television Interface Circuit the process: Atari’s goal was to conquer the nascent scene's fire. -

Once in a Blue Moon: Airmen in Theater Command Lauris Norstad, Albrecht Kesselring, and Their Relevance to the Twenty-First Century Air Force

COLLEGE OF AEROSPACE DOCTRINE, RESEARCH AND EDUCATION AIR UNIVERSITY AIR Y U SIT NI V ER Once in a Blue Moon: Airmen in Theater Command Lauris Norstad, Albrecht Kesselring, and Their Relevance to the Twenty-First Century Air Force HOWARD D. BELOTE Lieutenant Colonel, USAF CADRE Paper No. 7 Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112-6615 July 2000 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Belote, Howard D., 1963– Once in a blue moon : airmen in theater command : Lauris Norstad, Albrecht Kesselring, and their relevance to the twenty-first century Air Force/Howard D. Belote. p. cm. -- (CADRE paper ; no. 7) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-58566-082-5 1. United States. Air Force--Officers. 2. Generals--United States. 3. Unified operations (Military science) 4. Combined operations (Military science) 5. Command of troops. I. Title. II. CADRE paper ; 7. UG793 .B45 2000 358.4'133'0973--dc21 00-055881 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. This CADRE Paper, and others in the series, is available electronically at the Air University Research web site http://research.maxwell.af.mil under “Research Papers” then “Special Collections.” ii CADRE Papers CADRE Papers are occasional publications sponsored by the Airpower Research Institute of Air University’s (AU) College of Aerospace Doctrine, Research and Education (CADRE). Dedicated to promoting understanding of air and space power theory and application, these studies are published by the Air University Press and broadly distributed to the US Air Force, the Department of Defense and other governmental organiza- tions, leading scholars, selected institutions of higher learn- ing, public policy institutes, and the media. -

The Art of Computer Game Design the Art of Computer Game Design by Chris Crawford

The Art of Computer Game Design The Art of Computer Game Design by Chris Crawford Preface to the Electronic Version: This text was originally composed by computer game designer Chris Crawford in 1982. When searching for literature on the nature of gaming and its relationship to narrative in 1997, Prof. Sue Peabody learned of The Art of Computer Game Design, which was then long out of print. Prof. Peabody requested Mr. Crawford's permission to publish an electronic version of the text on the World Wide Web so that it would be available to her students and to others interested in game design. Washington State University Vancouver generously made resources available to hire graphic artist Donna Loper to produce this electronic version. WSUV currently houses and maintains the site. Correspondance regarding this site should be addressed to Prof. Sue Peabody, Department of History, Washington State University Vancouver, [email protected]. If you are interested in more recent writings by Chris Crawford, see the "Reflections" interview at the end of The Art of Computer Game Design. Also, visit Chris Crawford's webpage, Erasmatazz. An acrobat version of this text is mirrored at this site: Acrobat Table of Contents ■ Acknowledgement ■ Preface ■ Chapter 1 - What is a Game? ■ Chapter 2 - Why Do People Play Games? ■ Chapter 3 - A Taxonomy of Computer Games ■ Chapter 4 - The Computer as a Game Technology ■ Chapter 5 - The Game Design Sequence ■ Chapter 6 - Design Techniques and Ideals ■ Chapter 7 - The Future of Computer Games ■ Chapter 8 - Development of Excalibur ■ Reflections - Interview with Chris WSUV Home Page | Prof.