Slut-Shaming Metaphorologies: on Sexual Metaphor in Goethe's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is It About the Walls?: “The Police Or Ministers Should’Ve Been Better

Acknowledgements The study team for this project would like to sincerely thank the following persons for their support whether it came in financial, verbal, intellectual, institutional permission or “in kind” form: Harold Clarke, Director of the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services; Frank Hopkins, Assistant Director of Institutions, Nebraska Department of Correctional Services; Steve King, Nebraska Department of Correctional Services Director of Research; John Dahm, Warden of the Nebraska Correctional Center for Women; Ruta Snipes, Administrative Assistant to Warden Dahm; Rex Richard, Superintendent of the Community Correctional Center, Lincoln; Rape Spouse Abuse Crisis Center (RSACC); the steering committee for the project; Lisa Brubaker RSACC Trainer extraordinaire; T.J. McDowell, Director of The Lighthouse; Kristi Pffeifer, counselor at The Lighthouse; Rose Hughes, counselor at The Lighthouse; The Lighthouse, for providing space for our domestic violence training session; S. Bennett Mercurio, Chair of Communication Arts, Bellevue University for her discussions about the psychology of communication; steering committee member Patricia Lynch for her consultations on developments in the project; The Community Health Endowment Foundation; The Lozier Foundation; Friends of the Lincoln-Lancaster Women’s Commission; Woods Charitable Fund; Friendship Home; Larry Garnett, for discussions of ideas related to the project. A particular thank you is offered to Steven Zacharius, Jessica Ricketts McClean, and Karen Thomas of Kensington Publishing Corporation who immediately granted the study team’s request for donation of their publication SOULS OF OUR SISTERS: AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN BREAK THEIR SILENCE, TELL THEIR STORIES, AND HEAL THEIR SPIRITS (Daniels/Sandy authors and editors) which we deemed could enrich the participants lives and which their surprised and delighted reactions attested, every time, that the volume did. -

Muthal Paavam Tamil Movie

Muthal Paavam Tamil Movie 1 / 3 muthal paavam tamil movie muthal paavam tamil movie online muthal paavam tamil movie free download muthal paavam tamil film Vaibhavi....Shandilya....is....an....Indian....film....actress....who....has....appeared....in....Marathi....and.. ..Tamil.........I....Felt....Paavam....For.........Sakka....Podu....Podu....Raja....Movie....Posted....on....Decem ber...... Muthal...Muthalil...(Aaha)...-...Hariharan...Compilations...Various...Muthal...Muthalil...(Aaha)...- ...Hariharan...Free...Download.. View....Muthal....Paavam....movie....Songs....Track....List....and....get.. ..Muthal....Paavam....Song....Lyrics,....Muthal....Paavam....Movie....Song....High....Quality....High....Defi nition....Video....Songs........Spicyonion....Song....Database. Listen....and....Download....songs....from... .tamil....movie....Aan....Paavam....released....in....1985,....Music....by....Ilayaraja,....Starring....Pandiya n,....Pandiarajan,....Seetha,....Revathi,V.....K.. Aan...Paavam...Movie...Songs...Download,...Aan...Paava m...Tamil...Audio...Download,...Movie...Mp3...Songs...Free...Download,...Aan...Paavam...1985...Movie. ..All...Audio...Mp3...Download,...Movie...Name:...Aan...Paavam..... Test...your...JavaScript,...CSS,...HTML...or...CoffeeScript...online...with...JSFiddle...code...editor.. Movie ...List....Movie...Index...A...to...E...List;.......Aan...Paavam...-...1985....Latest.......Latest;...Featured...pos ts;...Most...popular;.......Tamil...Karaoke.. Mudhal..Mariyadhai..is..a..1985..Tamil..feature..film..directe d..by..P.....Bharathiraja..saw..the..movie..after..my.....Vivek..did..a..spoof..of.."Muthal..Mariyathai"..in. -

![Downloaded by [New York University] at 06:54 14 August 2016 Classic Case Studies in Psychology](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8368/downloaded-by-new-york-university-at-06-54-14-august-2016-classic-case-studies-in-psychology-738368.webp)

Downloaded by [New York University] at 06:54 14 August 2016 Classic Case Studies in Psychology

Downloaded by [New York University] at 06:54 14 August 2016 Classic Case Studies in Psychology The human mind is both extraordinary and compelling. But this is more than a collection of case studies; it is a selection of stories that illustrate some of the most extreme forms of human behaviour. From the leader who convinced his followers to kill themselves to the man who lost his memory; from the boy who was brought up as a girl to the woman with several personalities, Geoff Rolls illustrates some of the most fundamental tenets of psychology. Each case study has provided invaluable insights for scholars and researchers, and amazed the public at large. Several have been the inspiration for works of fiction, for example the story of Kim Peek, the real Rain Man. This new edition features three new case studies, including the story of Charles Decker who was tried for the attempted murder of two people but acquitted on the basis of a neurological condition, and Dorothy Martin, whose persisting belief in an impending alien invasion is an illuminating example of cognitive dissonance. In addition, each case study is contextualized with more typical behaviour, while the latest thinking in each sub-field is also discussed. Classic Case Studies in Psychology is accessibly written and requires no prior knowledge of psychology, but simply an interest in the human condition. It is a book that will amaze, sometimes disturb, but above all enlighten its readers. Downloaded by [New York University] at 06:54 14 August 2016 Geoff Rolls is Head of Psychology at Peter Symonds College in Winchester and formerly a Research Fellow at Southampton University, UK. -

Book of the Discovery Channel Documentary "Out of Eden/The Real Eve" (2002) by Stephen Oppenheimer

Book of the Discovery Channel Documentary "Out of Eden/The Real Eve" (2002) by Stephen Oppenheimer The book manuscript was originally titled: “Exodus: the genetic trail out of Africa” and was submitted by the author to Constable Robinson publishers also in June 2002, was accepted, edited and then multiply published 2003/4 in UK, USA & South Africa as: Out of Eden: The peopling of the world”(UK) The Real Eve: Modern Man's Journey Out of Africa”(US) & “Out of Africa's Eden: the peopling of the world”(SA) … and subsequently in various foreign translations The document following below contains parts of the author’s original text as submitted to the publisher. It includes the summary Contents pages for the 7 chapters, but also gives full text for the original Preface, Prologue and Epilogue : Contents (Full author’s copyright submitted text of Preface, Prologue and Epilogue follow ‘Contents’) Preface 5 Prologue: 9 1: Why us? Where do we come from? - Why us - The climate our teacher - Walking apes - Growing brains in the big dry- Why did we grow big brains? II. Talking apes Touched with the gift of speech? - Baldwin's idea - Ever newer models - How did our brain grow and what does it do for us? - Redundant computing power or increasing central control? - Food for thought or just talking about food? - Symbolic thought and Language: purely human abilities? - Speech and higher thought: big bang creation or gradual evolution? Chapter 1: Out of Africa 32 Introduction - Cardboard keys to Life - A Black Eve - Objections from multi-regionalists - Objections -

Benthic Data Sheet

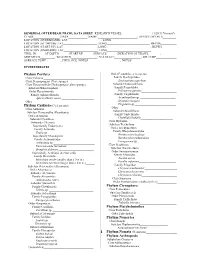

DEMERSAL OTTER/BEAM TRAWL DATA SHEET RESEARCH VESSEL_____________________(1/20/13 Version*) CLASS__________________;DATE_____________;NAME:___________________________; DEVICE DETAILS_________ LOCATION (OVERBOARD): LAT_______________________; LONG______________________________ LOCATION (AT DEPTH): LAT_______________________; LONG_____________________________; DEPTH___________ LOCATION (START UP): LAT_______________________; LONG______________________________;.DEPTH__________ LOCATION (ONBOARD): LAT_______________________; LONG______________________________ TIME: IN______AT DEPTH_______START UP_______SURFACE_______.DURATION OF TRAWL________; SHIP SPEED__________; WEATHER__________________; SEA STATE__________________; AIR TEMP______________ SURFACE TEMP__________; PHYS. OCE. NOTES______________________; NOTES_______________________________ INVERTEBRATES Phylum Porifera Order Pennatulacea (sea pens) Class Calcarea __________________________________ Family Stachyptilidae Class Demospongiae (Vase sponge) _________________ Stachyptilum superbum_____________________ Class Hexactinellida (Hyalospongia- glass sponge) Suborder Subsessiliflorae Subclass Hexasterophora Family Pennatulidae Order Hexactinosida Ptilosarcus gurneyi________________________ Family Aphrocallistidae Family Virgulariidae Aphrocallistes vastus ______________________ Acanthoptilum sp. ________________________ Other__________________________________________ Stylatula elongata_________________________ Phylum Cnidaria (Coelenterata) Virgularia sp.____________________________ Other_______________________________________ -

THE GENUS PHILINE (OPISTHOBRANCHIA, GASTROPODA) Downloaded from by Guest on 27 September 2021 W

Proc. malac. Soc. Lend. (1972) 40, 171. THE GENUS PHILINE (OPISTHOBRANCHIA, GASTROPODA) Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mollus/article/40/3/171/1087467 by guest on 27 September 2021 W. B. RUDMAN Department of Zoology, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand INTRODUCTION An earlier study of Philine angasi and Philine auriformis, from New Zealand (Rudman, 1972), showed some interesting variations in the structure of the foregut. Specimens of P. falklandica and P. gibba, from Antarctica, were subsequently studied and with P. quadrata and P. powelli these species exhibit an interesting range of development within the genus. EXTERNAL FEATURES AND MANTLE CAVITY The external features of the animal, and structure of the mantle cavity are similar in all species studied. Published information shows these features are constant throughout the genus (Franz and Clark, 1969; Horikoshi, 1967; Mattox, 1958; Sars, 1878; Vayssiere, 1885). The following description is based on Philine auriformis Suter, 1909; for illustrations of P. auriformis, P. angasi and P. powelli, see Rudman (1970). The animal is elongate and the head shield is approximately two-thirds the length of the body. The posterior edge of the head shield sometimes has a median indentation and a thin median line, free of cilia, runs the length of the shield. The posterior or mantle shield, approximately one-third of the body-length, arises from under the head shield and extends some distance beyond the foot. There is usually a median notch on the posterior edge of this shield. The shell is internal and, as in the Aglajidae, there is a narrow ciliated duct running from the shell cavity to open in the left posterior quarter of the mantle shield. -

Gedenktafeln in Weimar

Gedenktafeln in Weimar Hinweise: Diese Übersicht erhebt keinen Anspruch auf Vollständigkeit. Das Stadtarchiv Weimar ist für Korrektur- und Ergänzungshinweise (auch zu heute nicht mehr vorhandenen Tafeln) sowie für die Überlassung besserer Fotografien dankbar. Name Ort Inhalt Bild A Abendroth, Hermann Jahnstraße 14 Tafel nicht mehr vorhanden Ahner, Alfred Thomas-Müntzer-Str. 22 Hier wohnte 1946-1973 der Maler ALFRED AHNER 13.08.1890-12.11.1973 AIDS-Hilfe - Dreizeiler Frauentorstraße Dreizeiler für Weimar seit 1994 Diese Installation erinnert an Menschen, die an AIDS verstorben sind. Sie ist Teil des Projektes „Denkraum: NAMAN und STEINE“ der deutschen AIDS-Stiftung, Bonn und des Künstlers Tom Fecht AIDS-Hilfe Weimar & Ostthüringen e.V. Alliierte / Übergabe der Markt 1 IN GEDENKEN AN DIE EHRENHAFTE Stadt 1945 ÜBERGABE VON WEIMAR AN DIE 80. AMERIKANISCHE INFANTERIEDIVISION AM 12. APRIL 1945 1 Name Ort Inhalt Bild Alte Mühle Tiefurt, Hauptstraße MÜHLE TIEFURT Die erste Erwähnung ist im Lehnbrief der Marschälle in Tiefurt aus dem Jahr 1311 zu finden. War es erst eine Getreidemühle, die 1332 zu einer Ölmühle erweitert wurde, so wurde sie Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts zu einer Papiermühle und Kartonagenfabrik umgestaltet. 1899 wurde im Zuge des Technischen Fortschritts eine Francisturbine eingebaut. Die Wehranlage an der Ilm wurde infolge von Hochwasser mehrfach zerstört. 1970 unterblieb die Instandsetzung. Die alte Turbine verrostete im Schlamm. Die Tiefurter „Pappenbude“ stellte jedoch erst 1991 den Betrieb ein. Die ehemalige 5t schwere Mischkugel sowie das Kammrad der Turbine und einiges Zubehör stehen jetzt als technisches Denkmal neben der Mühle (…) Altenburg Jenaer Straße 3 (siehe unter Franz Liszt) Andersen, Hans-Christian Am Markt 16 Hans-Christian Andersen 1805-1875 dänischer Schriftsteller und Dichter weilte ab 1844 mehrmals in Weimar Ansprache an Weimarer Friedrich-Ebert-Str. -

Abstract Volume

ABSTRACT VOLUME August 11-16, 2019 1 2 Table of Contents Pages Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………………...1 Abstracts Symposia and Contributed talks……………………….……………………………………………3-225 Poster Presentations…………………………………………………………………………………226-291 3 Venom Evolution of West African Cone Snails (Gastropoda: Conidae) Samuel Abalde*1, Manuel J. Tenorio2, Carlos M. L. Afonso3, and Rafael Zardoya1 1Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (MNCN-CSIC), Departamento de Biodiversidad y Biologia Evolutiva 2Universidad de Cadiz, Departamento CMIM y Química Inorgánica – Instituto de Biomoléculas (INBIO) 3Universidade do Algarve, Centre of Marine Sciences (CCMAR) Cone snails form one of the most diverse families of marine animals, including more than 900 species classified into almost ninety different (sub)genera. Conids are well known for being active predators on worms, fishes, and even other snails. Cones are venomous gastropods, meaning that they use a sophisticated cocktail of hundreds of toxins, named conotoxins, to subdue their prey. Although this venom has been studied for decades, most of the effort has been focused on Indo-Pacific species. Thus far, Atlantic species have received little attention despite recent radiations have led to a hotspot of diversity in West Africa, with high levels of endemic species. In fact, the Atlantic Chelyconus ermineus is thought to represent an adaptation to piscivory independent from the Indo-Pacific species and is, therefore, key to understanding the basis of this diet specialization. We studied the transcriptomes of the venom gland of three individuals of C. ermineus. The venom repertoire of this species included more than 300 conotoxin precursors, which could be ascribed to 33 known and 22 new (unassigned) protein superfamilies, respectively. Most abundant superfamilies were T, W, O1, M, O2, and Z, accounting for 57% of all detected diversity. -

Creation: the (Killer) Lesson Plan the Story of The

A Calling to the City Creation: the (Killer) Lesson Plan Getting to the Crux of the Adventist Biology Education Debate The Story of the English Bible New Tools for People of the Book When What is True is Not Pure Reading the Bible Sculpture Series VOLUME 39 ISSUE 2 n spring 2011 SPECTRUM is a journal established to encourage Seventh-day Adventist participation in the discus- sion of contemporary issues from a Christian viewpoint, to look without prejudice at all sides of a subject, to evaluate the merits of diverse views, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED COPYRIGHT © 2011 ADVENTIST FORUM and to foster Christian intellectual and cultural growth. Although effort is made to ensure accu- rate scholarship and discriminating judgment, the statements of fact are the responsibility of con- Editor Bonnie Dwyer tributors, and the views individual authors express Editorial Assistant Heather Langley are not necessarily those of the editorial staff as a Copy Editor Ramona Evans whole or as individuals. Design Laura Lamar Media Projects Alexander Carpenter SPECTRUM is published by Adventist Forum, a Spectrum Web Team Alexander Carpenter, Rachel nonsubsidized, nonprofit organization for which Davies, Bonnie Dwyer, Rich Hannon, David R. Larson, gifts are deductible in the report of income for pur- Cover Art: “Hooked.” Jonathan Pichot, Wendy Trim, Jared Wright Mixed media, 2011. poses of taxation. The publishing of SPECTRUM Bible: The Holy Bible: New depends on subscriptions, gifts from individuals, International Version. Grand and the voluntary efforts of the contributors. Rapids: Zondervan, 1984. EDITORIAL BOARD Richard Rice Theology SPECTRUM can be accessed on the World Wide Artist Biography: Born Beverly Beem Loma Linda University Web at www.spectrummagazine.org and raised in South Africa, English John McDowell completed Walla Walla College Charles Scriven high school at Helderberg President College. -

Midwater Data Sheet

MIDWATER TRAWL DATA SHEET RESEARCH VESSEL__________________________________(1/20/2013Version*) CLASS__________________;DATE_____________;NAME:_________________________; DEVICE DETAILS___________ LOCATION (OVERBOARD): LAT_______________________; LONG___________________________ LOCATION (AT DEPTH): LAT_______________________; LONG______________________________ LOCATION (START UP): LAT_______________________; LONG______________________________ LOCATION (ONBOARD): LAT_______________________; LONG______________________________ BOTTOM DEPTH_________; DEPTH OF SAMPLE:____________; DURATION OF TRAWL___________; TIME: IN_________AT DEPTH________START UP__________SURFACE_________ SHIP SPEED__________; WEATHER__________________; SEA STATE_________________; AIR TEMP______________ SURFACE TEMP__________; PHYS. OCE. NOTES______________________; NOTES_____________________________ INVERTEBRATES Lensia hostile_______________________ PHYLUM RADIOLARIA Lensia havock______________________ Family Tuscaroridae “Round yellow ones”___ Family Hippopodiidae Vogtia sp.___________________________ PHYLUM CTENOPHORA Family Prayidae Subfamily Nectopyramidinae Class Nuda "Pointed siphonophores"________________ Order Beroida Nectadamas sp._______________________ Family Beroidae Nectopyramis sp.______________________ Beroe abyssicola_____________________ Family Prayidae Beroe forskalii________________________ Subfamily Prayinae Beroe cucumis _______________________ Craseoa lathetica_____________________ Class Tentaculata Desmophyes annectens_________________ Subclass -

An Annotated Checklist of the Marine Macroinvertebrates of Alaska David T

NOAA Professional Paper NMFS 19 An annotated checklist of the marine macroinvertebrates of Alaska David T. Drumm • Katherine P. Maslenikov Robert Van Syoc • James W. Orr • Robert R. Lauth Duane E. Stevenson • Theodore W. Pietsch November 2016 U.S. Department of Commerce NOAA Professional Penny Pritzker Secretary of Commerce National Oceanic Papers NMFS and Atmospheric Administration Kathryn D. Sullivan Scientific Editor* Administrator Richard Langton National Marine National Marine Fisheries Service Fisheries Service Northeast Fisheries Science Center Maine Field Station Eileen Sobeck 17 Godfrey Drive, Suite 1 Assistant Administrator Orono, Maine 04473 for Fisheries Associate Editor Kathryn Dennis National Marine Fisheries Service Office of Science and Technology Economics and Social Analysis Division 1845 Wasp Blvd., Bldg. 178 Honolulu, Hawaii 96818 Managing Editor Shelley Arenas National Marine Fisheries Service Scientific Publications Office 7600 Sand Point Way NE Seattle, Washington 98115 Editorial Committee Ann C. Matarese National Marine Fisheries Service James W. Orr National Marine Fisheries Service The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS (ISSN 1931-4590) series is pub- lished by the Scientific Publications Of- *Bruce Mundy (PIFSC) was Scientific Editor during the fice, National Marine Fisheries Service, scientific editing and preparation of this report. NOAA, 7600 Sand Point Way NE, Seattle, WA 98115. The Secretary of Commerce has The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series carries peer-reviewed, lengthy original determined that the publication of research reports, taxonomic keys, species synopses, flora and fauna studies, and data- this series is necessary in the transac- intensive reports on investigations in fishery science, engineering, and economics. tion of the public business required by law of this Department. -

Nature, Weber and a Revision of the French Sublime

Nature, Weber and a Revision of the French Sublime Naturaleza, Weber y una revisión del concepto francés de lo sublime Joseph E. Morgan Nature, Weber, and a Revision of the French Sublime Joseph E. Morgan This article investigates the emergence Este artículo aborda la aparición y and evolution of two mainstream evolución de dos de los grandes temas romantic tropes (the relationship románticos, la relación entre lo bello y between the beautiful and the sublime lo sublime, así como la que existe entre as well as that between man and el hombre y la naturaleza, en la nature) in the philosophy, aesthetics filosofía, la estética y la pintura de la and painting of Carl Maria von Weber’s época de Carl Maria von Weber. El foco time, directing it towards an analysis of se dirige hacia el análisis de la expresión Weber’s musical style and expression as y el estilo musicales de Weber, tal y manifested in his insert aria for Luigi como se manifiesta en la inserción de Cherubini’s Lodoïska “Was Sag Ich,” (J. su aria “Was sag ich?” (J.239) que 239). The essay argues that the escribió para la ópera Lodoïska de Luigi cosmopolitan characteristic of Weber’s Cherubini. Este estudio propone que el operatic expression, that is, his merging carácter cosmopolita de las óperas de of French and Italian styles of operatic Weber (con su fusión de los estilos expression, was a natural consequence operísticos francés e italiano) fue una of his participation in the synaesthetic consecuencia natural de su movement of the Romantic era.