Dune Grass (Southern Subtype)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Revised February 24, 2017 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org C ur Alleghany rit Ashe Northampton Gates C uc Surry am k Stokes P d Rockingham Caswell Person Vance Warren a e P s n Hertford e qu Chowan r Granville q ot ui a Mountains Watauga Halifax m nk an Wilkes Yadkin s Mitchell Avery Forsyth Orange Guilford Franklin Bertie Alamance Durham Nash Yancey Alexander Madison Caldwell Davie Edgecombe Washington Tyrrell Iredell Martin Dare Burke Davidson Wake McDowell Randolph Chatham Wilson Buncombe Catawba Rowan Beaufort Haywood Pitt Swain Hyde Lee Lincoln Greene Rutherford Johnston Graham Henderson Jackson Cabarrus Montgomery Harnett Cleveland Wayne Polk Gaston Stanly Cherokee Macon Transylvania Lenoir Mecklenburg Moore Clay Pamlico Hoke Union d Cumberland Jones Anson on Sampson hm Duplin ic Craven Piedmont R nd tla Onslow Carteret co S Robeson Bladen Pender Sandhills Columbus New Hanover Tidewater Coastal Plain Brunswick THE COUNTIES AND PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF NORTH CAROLINA Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org This list is dynamic and is revised frequently as new data become available. New species are added to the list, and others are dropped from the list as appropriate. -

Yucca Gloriosa

Yucca gloriosa COMMON NAME Spanish dagger, palm lily, mound-lily yucca FAMILY Agavaceae AUTHORITY L. FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Exotic STRUCTURAL CLASS Herbs - Monocots HABITAT Occur naturally on coastal dunes and shell mounds near the Atlantic, from North Carolina to north-east Florida. FEATURES An erect evergreen shrub with swordlike leaves about 5 cm wide and 0.6-0.9 m long originating from a basal rosette. The leaves are bluish or grayish green with smooth margins and pointed tips. They tend to bend near the middle and arch downward. In summer mound-lily yucca puts up a showy 6-8 ft (1.8-2.4 m) spike of fragrant flowers that are white with purplish tinges, pendant and about 7.6 cm across. Mound-lily yucca stays in a stemless rounded clump 2-5 ft (0.6-1.5 m) across and about the same height for several years, but eventually develops a trunk or stem which elevates that clump of leaves above the ground as much as 1.8-2.4 m. In older plants the stem develops branches and each terminus has its own Yucca gloriosa. Photographer: John Smith- rosette of leaves. Dodsworth SIMILAR TAXA The cultivar, Nobilis has dark green leaves and Variegata has leaves with yellow margins. FLOWERING Summer FLOWER COLOURS Violet/Purple, White PROPAGATION TECHNIQUE Seed and stem and root fragments. YEAR NATURALISED 1970 ORIGIN N. America ETYMOLOGY yucca: An name derived from a language in the Carib group, denoting another plant and mistakenly applied to this taxa. Yucca gloriosa. Photographer: John Smith- MORE INFORMATION Dodsworth https://www.nzpcn.org.nz/flora/species/yucca-gloriosa/. -

Transcript Profiling of a Novel Plant Meristem, the Monocot Cambium

Journal of Integrative JIPB Plant Biology Transcript profiling of a novel plant meristem, the monocot cambiumFA Matthew Zinkgraf1,2, Suzanne Gerttula1 and Andrew Groover1,3* 1. US Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station, Davis, California, USA 2. Department of Computer Science, University of California, Davis, USA 3. Department of Plant Biology, University of California, Davis, USA Article *Correspondence: Andrew Groover ([email protected]) doi: 10.1111/jipb.12538 Abstract While monocots lack the ability to produce a xylem tissues of two forest tree species, Populus Research vascular cambium or woody growth, some monocot trichocarpa and Eucalyptus grandis. Monocot cambium lineages evolved a novel lateral meristem, the monocot transcript levels showed that there are extensive overlaps cambium, which supports secondary radial growth of between the regulation of monocot cambia and vascular stems. In contrast to the vascular cambium found in woody cambia. Candidate regulatory genes that vary between the angiosperm and gymnosperm species, the monocot monocot and vascular cambia were also identified, and cambium produces secondary vascular bundles, which included members of the KANADI and CLE families involved have an amphivasal organization of tracheids encircling a in polarity and cell-cell signaling, respectively. We suggest central strand of phloem. Currently there is no information that the monocot cambium may have evolved in part concerning the molecular genetic basis of the develop- through reactivation of genetic mechanisms involved in ment or evolution of the monocot cambium. Here we vascular cambium regulation. report high-quality transcriptomes for monocot cambium Edited by: Chun-Ming Liu, Institute of Crop Science, CAAS, China and early derivative tissues in two monocot genera, Yucca Received Feb. -

Appendixes, Comprehensive Conservation Plan, Rainwater

Glossary accessible—Pertaining to physical access to areas and biological control—Use of organisms or viruses to activities for people of different abilities, especially control invasive plants or other pests. those with physical impairments. biological diversity, also biodiversity—Variety of life adaptive resource management—Rigorous application and its processes, including the variety of living of management, research, and monitoring to gain organisms, the genetic differences among them, and information and experience necessary to assess and the communities and ecosystems in which they occur modify management activities; a process that uses (The Fish and Wildlife Service Manual, 052 FW 1.12B). feedback from research, monitoring, and evaluation of The National Wildlife Refuge System’s focus is on management actions to support or modify objectives indigenous species, biotic communities, and ecological and strategies at all planning levels; a process in processes. which policy decisions are carried out within a framework of scientifi cally driven experiments to biotic—Pertaining to life or living organisms; caused, test predictions and assumptions inherent in a produced by, or comprising living organisms. management plan. Analysis of results helps managers CAFO—Concentrated animal-feeding operation. determine whether current management should continue as is or whether it should be modifi ed to canopy—Layer of foliage, generally the uppermost achieve desired conditions. layer, in a vegetative stand; midlevel or understory vegetation in multilayered stands; canopy closure Administration Act—National Wildlife Refuge System (also canopy cover) is an estimate of the amount of Administration Act of 1966. overhead vegetative cover. alternative —Reasonable way to solve an identifi ed catabolized (catabolism)—Breakdown of more complex problem or satisfy the stated need (40 CFR 1500.2); substances into simpler ones, with the release of one of several different means of accomplishing refuge energy. -

Lush & Efficient

R EVISED E DITION LLushush && EEfficientfficient LandscapeLandscape GardeningGardening inin thethe CoachellaCoachella ValleyValley Coachella Valley Water District LLushush && EEfficientfficient LandscapeLandscape GardeningGardening inin thethe CoachellaCoachella ValleyValley RR EVISEDEVISED EE DITIONDITION CoachellaCoachella ValleyValley WaterWater DistrictDistrict IRONWOOD PRESS Tucson, Arizona Coachella Valley Cover photo by Acknowledgements A special thank you goes to Water District Scott Millard Directors and staff of the Ann Copeland, now retired Coachella Valley Water District, Primary photography by Coachella Valley Water District from CVWD. An educational specialist who taught water CVWD, is a local govern- Scott Millard: © pages 5, 7, 8, 9, extend their gratitude to Scott ment agency controlled by Millard of Ironwood Press science to the children of five directors elected by the 10 (right), 11, 13, 14, 15, 17, 19, Coachella Valley, she took on 20, 21, 22 (left), 23, 24, 25, 26, in Tucson, Ariz., for bringing registered voters within its this revised book to fruition. the additional responsibility 1,000 square mile service area. 27, 28, 35, 38, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45 of working closely with Eric That area in the southeastern (top & lower right), 46 (top left, Scott and primary author Eric A. Johnson were partners at Johnson, reading his text and California desert extends from bottom center & bottom right), identifying photos to illustrate west of Palm Springs to the 47 (bottom left inset, bottom Ironwood Press and published communities along the Salton several excellent desert land- it. She also worked closely right & upper right), 48 (left & with contributing author Dave Sea. It is located primarily in upper left), 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, scaping books together before Riverside County but extends Harbison in developing and 55 (left & center inset & right), Eric’s death. -

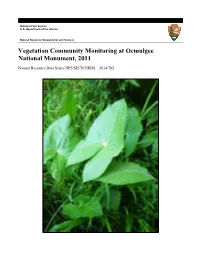

Vegetation Community Monitoring at Ocmulgee National Monument, 2011

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Vegetation Community Monitoring at Ocmulgee National Monument, 2011 Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2014/702 ON THE COVER Duck potato (Sagittaria latifolia) at Ocmulgee National Monument. Photograph by: Sarah C. Heath, SECN Botanist. Vegetation Community Monitoring at Ocmulgee National Monument, 2011 Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2014/702 Sarah Corbett Heath1 Michael W. Byrne2 1USDI National Park Service Southeast Coast Inventory and Monitoring Network Cumberland Island National Seashore 101 Wheeler Street Saint Marys, Georgia 31558 2USDI National Park Service Southeast Coast Inventory and Monitoring Network 135 Phoenix Road Athens, Georgia 30605 September 2014 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Data Series is intended for the timely release of basic data sets and data summaries. Care has been taken to assure accuracy of raw data values, but a thorough analysis and interpretation of the data has not been completed. Consequently, the initial analyses of data in this report are provisional and subject to change. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

TAXON:Yucca Gloriosa L. SCORE:11.0 RATING:High Risk

TAXON: Yucca gloriosa L. SCORE: 11.0 RATING: High Risk Taxon: Yucca gloriosa L. Family: Asparagaceae Common Name(s): palmlilja Synonym(s): Yucca acuminata Sweet Spanish dagger Yucca acutifolia Truff. Yucca ellacombei Baker Yucca ensifolia Groenl. Yucca integerrima Stokes Yucca obliqua Haw. Yucca patens André Yucca plicata (Carrière) K.Koch Yucca plicatilis K.Koch Yucca pruinosa Baker Yucca tortulata Baker Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 15 Nov 2017 WRA Score: 11.0 Designation: H(HPWRA) Rating: High Risk Keywords: Naturalized, Weedy Succulent, Spine-tipped Leaves, Moth-pollinated Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) Intermediate tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 y Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 y 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 304 Environmental weed 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 y Creation Date: 15 Nov 2017 (Yucca gloriosa L.) Page 1 of 21 TAXON: Yucca gloriosa L. -

Yucca Gloriosa

Yucca gloriosa Yucca gloriosa is a species of flowering plant in the family Asparagaceae, native to the beach scrub and sandy lowlands of the southeastern United States, from the Outer Banksof Virginia and North Carolina to Florida and the coastal bend of Texas. It is also widely cultivated as an ornamental and reportedly has become established in the wild in Italy, Turkey, Mauritius, Réunion, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, Argentina, Chile and Uruguay. Common names include:- Adam's needle Moundlily Yucca Soft-tipped Yucca Glorious Yucca Palm Lily Spanish Bayonet Lord's candlestick Roman Candle Spanish-dagger Mound Lily Sea Islands Yucca Tree Lily Description Yucca gloriosa is an evergreen shrub. The plant is known to grow to heights above 5 m (16 feet). It is caulescent, usually with several stems arising from the base, the base thickening in adult specimens. The long narrow leaves are straight and very stiff, growing to 30–50 cm (12–20 in) long and 2-3.5 cm wide. They are dark green with entire margins, smooth, rarely finely denticulate, acuminate, with a sharp brown terminal spine. Inflorescence is a panicle up to 2.5 m (8 ft) long, of bell-shaped white flowers, sometimes tinged purple or red. Fruit is a leathery, elongate berry up to 8 cm long. Habitat Yucca gloriosa grows on sand dunes along the coast and barrier islands of the subtropical southeastern USA, often together with Yucca aloifolia and a variety formerly called Yucca recurvifolia or Y. gloriosa var. recurvifolia, now Y. gloriosa var. tristis. In contrast to Y. -

Ecology and Evolution of Southeastern United States Yucca Species

ECOLOGY AND EVOLUTION OF SOUTHEASTERN UNITED STATES YUCCA SPECIES by JEREMY DANIEL RENTSCH (Under the Direction of JIM LEEBENS-MACK) ABSTRACT The genus Yucca contains approximately 40 species with most diversity found in Mexico and the southwestern United States. The southeastern United States is home to three well- described yucca species: the fleshy-fruited Y. aloifolia, the capsular-fruited Y. filamentosa, and Y. gloriosa – with a fruit type that does not follow convention. Yucca species are perhaps best known for the obligate pollination mutualism they share with moths in the genera Tegeticula and Parategeticula. Such interactions are thought to be highly specialized, restricting gene flow between species and even make evolutionary reversions to generalist life history characterizes impossible. Here, we show that Y. gloriosa is an intersectional, homploid, hybrid species produced by the crossing of Y. aloifolia and Y. filamentosa. We go on to show that Y. aloifolia has escaped from the obligate pollination mutualism and is being pollinated diurnally by the introduced European honey bee, Apis mellifera – an observation that directly refutes the idea that highly specialized species interactions lead to evolutionary dead ends. Finally, we utilized high throughput sequencing a biotinylated probe set in order to sequence many genes of interest in Y. aloifolia, laying the ground work to better understand its introduction history and pattern of pollinator association. INDEX WORDS: Yucca, hybrid speciation, population genetics, obligate mutualism ECOLOGY AND EVOLUTION OF SOUTHEASTERN UNITED STATES YUCCA SPECIES by JEREMY DANIEL RENTSCH BS, Kent State University, 2007 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ATHENS, GEORGIA 2013 © 2013 Jeremy D. -

Nueces County Plant List

710 E. Main, Suite 1 (361) 767-5217 - Phone Robstown, TX 78380 (361) 767-5248 - Fax NUECES COUNTY LANDSCAPE PLANT LIST COMMON NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME HABIT LIGHT WATER SALT TOL. TX. NATIVE COMMENT GROUND COVER Asparagus fern Asparagus sprengeri Evergreen F/P L Y N Perennial Spider Plant, Airplane Plant Chlorophytum comosum Perennial F/P/S M N N May freeze Fig Ivy Ficus pumila Perennial F/P/S M N N Creeping Vine Shore Juniper Juniperus conferta Evergreen F M N N Trailing Juniper Juniperus horizontalis. Evergreen F M N N Bar Harbor, Blue Rug Tam Trailing Lantana Lantana montevidensis Simi - F L N Y Trailing Purple or White Deciduous Lighting Lily Turf, Liriope, Big Blue Liriope muscari Evergreen P/S M N N Mondo Grass, Monkey Grass Ophiopogon japonicus Evergreen P/S M N N Trailing Rosemary Rosemarinus prostrata Evergreen F/P L/M N N Needs drainage Purple Heart Setcreasea pallida Evergreen P/S M N N Arrowhead plant Syngunium podophyllum Evergreen P/S M N N Vine Asiatic Jasmine Trachelospermum asiaticum Evergreen F/S L Y N Verbena Verbena spp. Perennial F L N Y Wedelia Wedelia trilobata Perennial F/P M Y N PALM Cocus Plumosa, Queen Palm Arecastrum romanzoffanum Evergreen F L Y N Half-hardy/25' Fast Grower Mexican Blue Palm Brahea armata Evergreen F L N N Not for the island Pindo, Cocos Australis, Jelly Butia capitata Evergreen F L Y N 1 COMMON NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME HABIT LIGHT WATER SALT TOL. TX. NATIVE COMMENT Mediterranean Fan Palm Chamaerops humulis Evergreen F L Y N Hardy, bushy to 10' Sago Palm Cycas revoluta Evergreen F L Y N Cycad - to -

Shared Expression of Crassulacean Acid Metabolism (CAM) Genes Predates the Origin of CAM in the Genus Yucca

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/371344; this version posted October 26, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Title: Shared expression of Crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) genes predates the origin of CAM in the genus Yucca. Karolina Heyduk1 ([email protected]), Jeremy N. Ray1 ([email protected]), Saaravanaraj Ayyampalayam2 ([email protected]), Nida Moledina1 ([email protected]), Anne Borland ([email protected]) 3, Scott A. Harding4,5 ([email protected]), Chung-Jui Tsai4,5 ([email protected]), Jim Leebens-Mack1 ([email protected]). Corresponding author: Karolina Heyduk ([email protected], Ph: +1-813-260-0659) 1 –Department of Plant Biology, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA 2 – Georgia Advanced Computing Resource Center, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA 3 – School of Natural and Environmental Sciences, Newcastle University, Newcastle, United Kingdom 4 – Department of Genetics, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA 5 – Warnell School of Forestry, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA Date of submission: 19/10/2018 Number of tables: 0 Number of figures: 7 Number of supplementary: 9 (5 figures, 4 tables) Word count: 6,484 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/371344; this version posted October 26, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

County of Riverside Friendly Plant List

ATTACHMENT A COUNTY OF RIVERSIDE CALIFORNIA FRIENDLY PLANT LIST PLANT LIST KEY WUCOLS III (Water Use Classification of Landscape Species) WUCOLS Region Sunset Zones 1 2,3,14,15,16,17 2 8,9 3 22,23,24 4 18,19,20,21 511 613 WUCOLS III Water Usage/ Average Plant Factor Key H-High (0.8) M-Medium (0.5) L-Low (.2) VL-Very Low (0.1) * Water use for this plant material was not listed in WUCOLS III, but assumed in comparison to plants of similar species ** Zones for this plant material were not listed in Sunset, but assumed in comparison to plants of similar species *** Zones based on USDA zones ‡ The California Friendly Plant List is provided to serve as a general guide for plant material. Riverside County has multiple Sunset Zones as well as microclimates within those zones which can affect plant viability and mature size. As such, plants and use categories listed herein are not exhaustive, nor do they constitute automatic approval; all proposed plant material is subject to review by the County. In some cases where a broad genus or species is called out within the list, there may be multiple species or cultivars that may (or may not) be appropriate. The specific water needs and sizes of cultivars should be verified by the designer. Site specific conditions should be taken into consideration in determining appropriate plant material. This includes, but is not limited to, verifying soil conditions affecting erosion, site specific and Fire Department requirements or restrictions affecting plans for fuel modifications zones, and site specific conditions near MSHCP areas.