Appendixes, Comprehensive Conservation Plan, Rainwater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Revised February 24, 2017 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org C ur Alleghany rit Ashe Northampton Gates C uc Surry am k Stokes P d Rockingham Caswell Person Vance Warren a e P s n Hertford e qu Chowan r Granville q ot ui a Mountains Watauga Halifax m nk an Wilkes Yadkin s Mitchell Avery Forsyth Orange Guilford Franklin Bertie Alamance Durham Nash Yancey Alexander Madison Caldwell Davie Edgecombe Washington Tyrrell Iredell Martin Dare Burke Davidson Wake McDowell Randolph Chatham Wilson Buncombe Catawba Rowan Beaufort Haywood Pitt Swain Hyde Lee Lincoln Greene Rutherford Johnston Graham Henderson Jackson Cabarrus Montgomery Harnett Cleveland Wayne Polk Gaston Stanly Cherokee Macon Transylvania Lenoir Mecklenburg Moore Clay Pamlico Hoke Union d Cumberland Jones Anson on Sampson hm Duplin ic Craven Piedmont R nd tla Onslow Carteret co S Robeson Bladen Pender Sandhills Columbus New Hanover Tidewater Coastal Plain Brunswick THE COUNTIES AND PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF NORTH CAROLINA Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org This list is dynamic and is revised frequently as new data become available. New species are added to the list, and others are dropped from the list as appropriate. -

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Yucca Gloriosa

Yucca gloriosa COMMON NAME Spanish dagger, palm lily, mound-lily yucca FAMILY Agavaceae AUTHORITY L. FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Exotic STRUCTURAL CLASS Herbs - Monocots HABITAT Occur naturally on coastal dunes and shell mounds near the Atlantic, from North Carolina to north-east Florida. FEATURES An erect evergreen shrub with swordlike leaves about 5 cm wide and 0.6-0.9 m long originating from a basal rosette. The leaves are bluish or grayish green with smooth margins and pointed tips. They tend to bend near the middle and arch downward. In summer mound-lily yucca puts up a showy 6-8 ft (1.8-2.4 m) spike of fragrant flowers that are white with purplish tinges, pendant and about 7.6 cm across. Mound-lily yucca stays in a stemless rounded clump 2-5 ft (0.6-1.5 m) across and about the same height for several years, but eventually develops a trunk or stem which elevates that clump of leaves above the ground as much as 1.8-2.4 m. In older plants the stem develops branches and each terminus has its own Yucca gloriosa. Photographer: John Smith- rosette of leaves. Dodsworth SIMILAR TAXA The cultivar, Nobilis has dark green leaves and Variegata has leaves with yellow margins. FLOWERING Summer FLOWER COLOURS Violet/Purple, White PROPAGATION TECHNIQUE Seed and stem and root fragments. YEAR NATURALISED 1970 ORIGIN N. America ETYMOLOGY yucca: An name derived from a language in the Carib group, denoting another plant and mistakenly applied to this taxa. Yucca gloriosa. Photographer: John Smith- MORE INFORMATION Dodsworth https://www.nzpcn.org.nz/flora/species/yucca-gloriosa/. -

Transcript Profiling of a Novel Plant Meristem, the Monocot Cambium

Journal of Integrative JIPB Plant Biology Transcript profiling of a novel plant meristem, the monocot cambiumFA Matthew Zinkgraf1,2, Suzanne Gerttula1 and Andrew Groover1,3* 1. US Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station, Davis, California, USA 2. Department of Computer Science, University of California, Davis, USA 3. Department of Plant Biology, University of California, Davis, USA Article *Correspondence: Andrew Groover ([email protected]) doi: 10.1111/jipb.12538 Abstract While monocots lack the ability to produce a xylem tissues of two forest tree species, Populus Research vascular cambium or woody growth, some monocot trichocarpa and Eucalyptus grandis. Monocot cambium lineages evolved a novel lateral meristem, the monocot transcript levels showed that there are extensive overlaps cambium, which supports secondary radial growth of between the regulation of monocot cambia and vascular stems. In contrast to the vascular cambium found in woody cambia. Candidate regulatory genes that vary between the angiosperm and gymnosperm species, the monocot monocot and vascular cambia were also identified, and cambium produces secondary vascular bundles, which included members of the KANADI and CLE families involved have an amphivasal organization of tracheids encircling a in polarity and cell-cell signaling, respectively. We suggest central strand of phloem. Currently there is no information that the monocot cambium may have evolved in part concerning the molecular genetic basis of the develop- through reactivation of genetic mechanisms involved in ment or evolution of the monocot cambium. Here we vascular cambium regulation. report high-quality transcriptomes for monocot cambium Edited by: Chun-Ming Liu, Institute of Crop Science, CAAS, China and early derivative tissues in two monocot genera, Yucca Received Feb. -

A List of Grasses and Grasslike Plants of the Oak Openings, Lucas County

A LIST OF THE GRASSES AND GRASSLIKE PLANTS OF THE OAK OPENINGS, LUCAS COUNTY, OHIO1 NATHAN WILLIAM EASTERLY Department of Biology, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, Ohio 4-3403 ABSTRACT This report is the second of a series of articles to be prepared as a second "Flora of the Oak Openings." The study represents a comprehensive survey of members of the Cyperaceae, Gramineae, Juncaceae, Sparganiaceae, and Xyridaceae in the Oak Openings region. Of the 202 species listed in this study, 34 species reported by Moseley in 1928 were not found during the present investigation. Fifty-seven species found by the present investi- gator were not observed or reported by Moseley. Many of these species or varieties are rare and do not represent a stable part of the flora. Changes in species present or in fre- quency of occurrence of species collected by both Moseley and Easterly may be explained mainly by the alteration of habitats as the Oak Openings region becomes increasingly urbanized or suburbanized. Some species have increased in frequency on the floodplain of Swan Creek, in wet ditches and on the banks of the Norfolk and Western Railroad right-of-way, along newly constructed roadsides, or on dry sandy sites. INTRODUCTION The grass family ranks third among the large plant families of the world. The family ranks number one as far as total numbers of plants that cover fields, mead- ows, or roadsides are concerned. No other family is used as extensively to pro- vide food or shelter or to create a beautiful landscape. The sedge family does not fare as well in terms of commercial importance, but the sedges do make avail- able forage and food for wild fowl and they do contribute plant cover in wet areas where other plants would not be as well adapted. -

A Phylogenetic Study in Carex Section Ovales (Cyperaceae) Using AFLP Data Andrew L

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 23 | Issue 1 Article 14 2007 Chromosome Number Changes Associated with Speciation in Sedges: a Phylogenetic Study in Carex section Ovales (Cyperaceae) Using AFLP Data Andrew L. Hipp University of Wisconsin, Madison Paul E. Rothrock Taylor University, Upland, Indiana Anton A. Reznicek University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Paul E. Berry University of Wisconsin, Madison Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Botany Commons, and the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Hipp, Andrew L.; Rothrock, Paul E.; Reznicek, Anton A.; and Berry, Paul E. (2007) "Chromosome Number Changes Associated with Speciation in Sedges: a Phylogenetic Study in Carex section Ovales (Cyperaceae) Using AFLP Data," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 23: Iss. 1, Article 14. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol23/iss1/14 Aliso 23, pp. 193–203 ᭧ 2007, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden CHROMOSOME NUMBER CHANGES ASSOCIATED WITH SPECIATION IN SEDGES: A PHYLOGENETIC STUDY IN CAREX SECTION OVALES (CYPERACEAE) USING AFLP DATA ANDREW L. HIPP,1,4,5 PAUL E. ROTHROCK,2 ANTON A. REZNICEK,3 AND PAUL E. BERRY1,6 1University of Wisconsin, Madison, Department of Botany, 430 Lincoln Drive, Madison, Wisconsin 53706, USA; 2Taylor University, Randall Environmental Studies Center, Upland, Indiana 46989-1001, USA; 3University of Michigan Herbarium, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, 3600 Varsity Drive, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48108-2287, USA 4Corresponding author ([email protected]) ABSTRACT Phylogenetic analysis of amplified fragment length polymorphisms (AFLP) was used to infer pat- terns of morphologic and chromosomal evolution in an eastern North American group of sedges (ENA clade I of Carex sect. -

Carex and Scleria

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societies Nebraska Academy of Sciences 1997 Keys and Distributional Maps for Nebraska Cyperaceae, Part 2: Carex and Scleria Steven B. Rolfsmeier Barbara Wilson Oregon State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tnas Part of the Life Sciences Commons Rolfsmeier, Steven B. and Wilson, Barbara, "Keys and Distributional Maps for Nebraska Cyperaceae, Part 2: Carex and Scleria" (1997). Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societies. 73. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tnas/73 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nebraska Academy of Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societiesy b an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1997. Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences, 24: 5-26 KEYS AND DISTRIBUTIONAL MAPS FOR NEBRASKA CYPERACEAE, PART 2: CAREX AND SCLERIA Steven B. Rolfsmeier and Barbara Wilson* 2293 Superior Road Department of Biology Milford, Nebraska 68405-8420 University of Nebraska at Omaha Omaha, Nebraska 68182-0040 *Present address: Department of Botany, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon ABSTRACT Flora GP are deleted based on misidentifications: Carex Keys and distributional maps are provided for the 71 species and one hybrid of Carex and single species of Scleria festucacea, C. haydenii, C. muehlenbergii var. enervis, documented for Nebraska. Six species-Carex albursina, C. C. normalis, C. siccata (reported as C. foenea), C. stricta, melanostachya, C. -

Carex of New England

Field Guide to Carex of New England Lisa A. Standley A Special Publication of the New England Botanical Club About the Author: Lisa A. Standley is an environmental consultant. She obtained a B.S, and M.S. from Cornell University and Ph.D. from the University of Washington. She has published several articles on the systematics of Carex, particularly Section Phacocystis, and was the author of several section treatments in the Flora of North America. Cover Illustrations: Pictured are Carex pensylvanica and Carex intumescens. Field Guide to Carex of New England Lisa A. Standley Special Publication of the New England Botanical Club Copyright © 2011 Lisa A. Standley Acknowledgements This book is dedicated to Robert Reed, who first urged me to write a user-friendly guide to Carex; to the memory of Melinda F. Denton, my mentor and inspiration; and to Tony Reznicek, for always sharing his expertise. I would like to thank all of the people who helped with this book in so many ways, particularly Karen Searcy and Robert Bertin for their careful editing; Paul Somers, Bruce Sorrie, Alice Schori, Pam Weatherbee, and others who helped search for sedges; Arthur Gilman, Melissa Dow Cullina, and Patricia Swain, who carefully read early drafts of the book; and to Emily Wood, Karen Searcy, and Ray Angelo, who provided access to the herbaria at Harvard University, the University of Massachusetts, and the New England Botanical Club. CONTENTS Introduction .......................................................................................................................1 -

Lush & Efficient

R EVISED E DITION LLushush && EEfficientfficient LandscapeLandscape GardeningGardening inin thethe CoachellaCoachella ValleyValley Coachella Valley Water District LLushush && EEfficientfficient LandscapeLandscape GardeningGardening inin thethe CoachellaCoachella ValleyValley RR EVISEDEVISED EE DITIONDITION CoachellaCoachella ValleyValley WaterWater DistrictDistrict IRONWOOD PRESS Tucson, Arizona Coachella Valley Cover photo by Acknowledgements A special thank you goes to Water District Scott Millard Directors and staff of the Ann Copeland, now retired Coachella Valley Water District, Primary photography by Coachella Valley Water District from CVWD. An educational specialist who taught water CVWD, is a local govern- Scott Millard: © pages 5, 7, 8, 9, extend their gratitude to Scott ment agency controlled by Millard of Ironwood Press science to the children of five directors elected by the 10 (right), 11, 13, 14, 15, 17, 19, Coachella Valley, she took on 20, 21, 22 (left), 23, 24, 25, 26, in Tucson, Ariz., for bringing registered voters within its this revised book to fruition. the additional responsibility 1,000 square mile service area. 27, 28, 35, 38, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45 of working closely with Eric That area in the southeastern (top & lower right), 46 (top left, Scott and primary author Eric A. Johnson were partners at Johnson, reading his text and California desert extends from bottom center & bottom right), identifying photos to illustrate west of Palm Springs to the 47 (bottom left inset, bottom Ironwood Press and published communities along the Salton several excellent desert land- it. She also worked closely right & upper right), 48 (left & with contributing author Dave Sea. It is located primarily in upper left), 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, scaping books together before Riverside County but extends Harbison in developing and 55 (left & center inset & right), Eric’s death. -

Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Dark Septate Fungi in Plants Associated with Aquatic Environments Doi: 10.1590/0102-33062016Abb0296

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and dark septate fungi in plants associated with aquatic environments doi: 10.1590/0102-33062016abb0296 Table S1. Presence of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) and/or dark septate fungi (DSF) in non-flowering plants and angiosperms, according to data from 62 papers. A: arbuscule; V: vesicle; H: intraradical hyphae; % COL: percentage of colonization. MYCORRHIZAL SPECIES AMF STRUCTURES % AMF COL AMF REFERENCES DSF DSF REFERENCES LYCOPODIOPHYTA1 Isoetales Isoetaceae Isoetes coromandelina L. A, V, H 43 38; 39 Isoetes echinospora Durieu A, V, H 1.9-14.5 50 + 50 Isoetes kirkii A. Braun not informed not informed 13 Isoetes lacustris L.* A, V, H 25-50 50; 61 + 50 Lycopodiales Lycopodiaceae Lycopodiella inundata (L.) Holub A, V 0-18 22 + 22 MONILOPHYTA2 Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum arvense L. A, V 2-28 15; 19; 52; 60 + 60 Osmundales Osmundaceae Osmunda cinnamomea L. A, V 10 14 Salviniales Marsileaceae Marsilea quadrifolia L.* V, H not informed 19;38 Salviniaceae Azolla pinnata R. Br.* not informed not informed 19 Salvinia cucullata Roxb* not informed 21 4; 19 Salvinia natans Pursh V, H not informed 38 Polipodiales Dryopteridaceae Polystichum lepidocaulon (Hook.) J. Sm. A, V not informed 30 Davalliaceae Davallia mariesii T. Moore ex Baker A not informed 30 Onocleaceae Matteuccia struthiopteris (L.) Tod. A not informed 30 Onoclea sensibilis L. A, V 10-70 14; 60 + 60 Pteridaceae Acrostichum aureum L. A, V, H 27-69 42; 55 Adiantum pedatum L. A not informed 30 Aleuritopteris argentea (S. G. Gmel) Fée A, V not informed 30 Pteris cretica L. A not informed 30 Pteris multifida Poir. -

Vegetation Community Monitoring at Ocmulgee National Monument, 2011

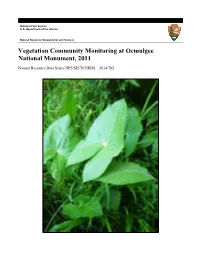

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Vegetation Community Monitoring at Ocmulgee National Monument, 2011 Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2014/702 ON THE COVER Duck potato (Sagittaria latifolia) at Ocmulgee National Monument. Photograph by: Sarah C. Heath, SECN Botanist. Vegetation Community Monitoring at Ocmulgee National Monument, 2011 Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2014/702 Sarah Corbett Heath1 Michael W. Byrne2 1USDI National Park Service Southeast Coast Inventory and Monitoring Network Cumberland Island National Seashore 101 Wheeler Street Saint Marys, Georgia 31558 2USDI National Park Service Southeast Coast Inventory and Monitoring Network 135 Phoenix Road Athens, Georgia 30605 September 2014 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Data Series is intended for the timely release of basic data sets and data summaries. Care has been taken to assure accuracy of raw data values, but a thorough analysis and interpretation of the data has not been completed. Consequently, the initial analyses of data in this report are provisional and subject to change. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

TAXON:Yucca Gloriosa L. SCORE:11.0 RATING:High Risk

TAXON: Yucca gloriosa L. SCORE: 11.0 RATING: High Risk Taxon: Yucca gloriosa L. Family: Asparagaceae Common Name(s): palmlilja Synonym(s): Yucca acuminata Sweet Spanish dagger Yucca acutifolia Truff. Yucca ellacombei Baker Yucca ensifolia Groenl. Yucca integerrima Stokes Yucca obliqua Haw. Yucca patens André Yucca plicata (Carrière) K.Koch Yucca plicatilis K.Koch Yucca pruinosa Baker Yucca tortulata Baker Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 15 Nov 2017 WRA Score: 11.0 Designation: H(HPWRA) Rating: High Risk Keywords: Naturalized, Weedy Succulent, Spine-tipped Leaves, Moth-pollinated Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) Intermediate tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 y Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 y 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 304 Environmental weed 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 y Creation Date: 15 Nov 2017 (Yucca gloriosa L.) Page 1 of 21 TAXON: Yucca gloriosa L.