The Potential of Introduction of Asian Vegetables in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Potential Impact of an Exotic Plant Invasion on Both Plant and Arthropod Communities in a Semi-Natural Grassland on Sugadaira Montane in Japan

Journal of Developments in Sustainable Agriculture 12: 52-64 (2017) Potential Impact of an Exotic Plant Invasion on Both Plant and Arthropod Communities in a Semi-natural Grassland on Sugadaira Montane in Japan Yukie Sato1*, Yuta Mashimo1,2, Ryo O. Suzuki1, Akira S. Hirao1, Etsuro Takagi1,3, Ryuji Kanai1, Daisuke Masaki1, Miyuki Sato1 and Ryuichiro Machida1 1 Sugadaira Montane Research Center, University of Tsukuba, Sugadaira Kogen 1278-294, Ueda, Nagano 386-2204, Japan 2 Graduate School of Symbiotic Systems Science and Technology, Fukushima University, Kanayagawa 1, Fukushima, Fukushima 960-1296, Japan 3 Department of Tourism Science, Tokyo Metropolitan University, 1-1 Minami-Osawa, Hachioji, Tokyo 192-0397, Japan Plant and arthropod communities interact closely with one another, therefore, invasive plants can alter not only plant communities, but may also have direct and indirect effects on arthropod communities. Here, we focus on the exotic giant ragweed, which is a serious invasive weed in Japan. Recently, the exotic plant invaded and has dominated part of a semi-natural grassland in Sugadaira Montane Research Center (Nagano Prefecture, Japan). We attempted to evaluate the potential impact of the invasive plant on both plant and arthropod communities by comparing the com- munity composition, abundance, species richness and diversity indices of plants and arthropods between areas where the exotic giant ragweed had and had not invaded, referred to as the invaded and reference areas respectively. We found significant differences in plant and arthropod community compositions between the areas. Plant species richness was lower in the invaded area as predicted. However, the abundance of arthropods including herbivores was higher in the invaded area compared to the reference area in contrast to the expectation that plant invasions reduce arthropod abundance and diversity. -

Minimum Dietary Diversity for Women a Guide to Measurement

FANTA III FOOD AND NUTRITION TECHNICAL A SSISTANCE Minimum Dietary Diversity for Women A Guide to Measurement Minimum Dietary Diversity for Women A Guide to Measurement Published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and USAID’s Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance III Project (FANTA), managed by FHI 360 Rome, 2016 Recommended citation: FAO and FHI 360. 2016. Minimum Dietary Diversity for Women: A Guide for Measurement. Rome: FAO. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), or of FANTA/FHI 360 concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO, or FHI 360 in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Additional funding for this publication was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the support of the Office of Health, Infectious Diseases, and Nutrition, Bureau for Global Health, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), under terms of Cooperative Agreement AID-OAA-A-12-00005 through the Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance III Project (FANTA), managed by FHI 360. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO, FHI 360, UC Davis, USAID or the U.S. -

Basic Beanery

344 appendix Basic Beanery name(s) origin & CharaCteristiCs soaking & Cooking Adzuki Himalayan native, now grown Soaked, Conventional Stovetop: 40 (aduki, azuki, red Cowpea, throughout Asia. Especially loved in minutes. unSoaked, Conventional Stovetop: red oriental) Japan. Small, nearly round red bean 1¼ hours. Soaked, pressure Cooker: 5–7 with a thread of white along part of minutes. unSoaked, pressure Cooker: the seam. Slightly sweet, starchy. 15–20 minutes. Lower in oligosaccharides. Anasazi New World native (present-day Soak? Yes. Conventional Stovetop: 2–2¹⁄² (Cave bean and new mexiCo junction of Arizona, New Mexico, hours. pressure Cooker: 15–18 minutes appaloosa—though it Colorado, Utah). White speckled with at full pressure; let pressure release isn’t one) burgundy to rust-brown. Slightly gradually. Slow-Cooker: 1¹⁄² hours on sweet, a little mealy. Lower in high, then 6 hours on low. oligosaccharides. Appaloosa New World native. Slightly elongated, Soak? Yes. Conventional Stovetop: 2–2¹⁄² (dapple gray, curved, one end white, the other end hours. pressure Cooker: 15–18 minutes; gray nightfall) mottled with black and brown. Holds let pressure release gradually. Slow- its shape well; slightly herbaceous- Cooker: 1¹⁄² hours on high, then 6–7 piney in flavor, a little mealy. Lower in hours on low. oligosaccharides. Black-eyed pea West African native, now grown and Soak? Optional. Soaked, Conventional (blaCk-eyes, lobia, loved worldwide. An ivory-white Stovetop: 20–30 minutes. unSoaked, Chawali) cowpea with a black “eye” across Conventional Stovetop: 45–55 minutes. the indentation. Distinctive ashy, Soaked, pressure Cooker: 5–7 minutes. mineral-y taste, starchy texture. unSoaked, pressure Cooker: 9–11 minutes. -

Sedges in Our Wetlands Typha Latifolia Schoeneplectus (Scirpus) Acutus • Native, Common, Sedge Family, up to 10’ Tall and S

TULE (COMMON and CALIFORNIA) CATTAIL, COMMON/BROAD-LEAVED BULLRUSH (COMMON and SOUTHERN) Sedges in Our Wetlands Typha latifolia Schoeneplectus (Scirpus) acutus • Native, common, sedge family, up to 10’ tall and S. californicus • Wetland Obligate in fresh water up to 0.8 m • Native, common, sedge family, up to10’ tall “Sedges have edges. Rushes are round. depth • Wetland Obligate, in standing freshwater Grasses have knees that bend to the ground. ” • Intrudes into marshes when salinity decreases marshes, can tolerate slight salinity Description: The Cyperaceae are a family of graminoid (grass-like), monocot- • Can block channels, but lays down in high flow • Rhizomatous, dense monotypic colony yledonous flowering plants known as sedges. The family is large, with some 5,500 • Used as a bioremediator to absorb pollutants known species described in about 90 genera, the largest being the "true sedges" ge- • Terminal panicle inflorescence nus Carex with over 2,000 species. The stems of Cyperaceae are often triangular • Can be weaved into baskets, mats, seats, and • California Tule – bright green triangular stems (found in and mostly solid, whereas those of grasses are never triangular and are usually hol- binding for tule canoes ECWRF ponds) low except at the nodes. Sedges differ from grasses in many features, most obvious- Ethnobotany: All parts of the cattail are edible ly in their sheaths and the arrangement of the leaves on the stem. The leaves are ar- • Common Tule – grey green round stem (found in Shollen- when gathered at the appropriate stage of growth. ranged such that they spiral around the stem in 3-ranks and have a basal portion that berger Park channel) The young shoots are cut from the rhizomes sheaths the stem. -

UPDATED 18Th February 2013

7th February 2015 Welcome to my new seed trade list for 2014-15. 12, 13 and 14 in brackets indicates the harvesting year for the seed. Concerning seed quantity: as I don't have many plants of each species, seed quantity is limited in most cases. Therefore, for some species you may only get a few seeds. Many species are harvested in my garden. Others are surplus from trade and purchase. OUT: Means out of stock. Sometimes I sell surplus seed (if time allows), although this is unlikely this season. NB! Cultivars do not always come true. I offer them anyway, but no guarantees to what you will get! Botanical Name (year of harvest) NB! Traditional vegetables are at the end of the list with (mostly) common English names first. Acanthopanax henryi (14) Achillea sibirica (13) Aconitum lamarckii (12) Achyranthes aspera (14, 13) Adenophora khasiana (13) Adenophora triphylla (13) Agastache anisata (14,13)N Agastache anisata alba (13)N Agastache rugosa (Ex-Japan) (13) (two varieties) Agrostemma githago (13)1 Alcea rosea “Nigra” (13) Allium albidum (13) Allium altissimum (Persian Shallot) (14) Allium atroviolaceum (13) Allium beesianum (14,12) Allium brevistylum (14) Allium caeruleum (14)E Allium carinatum ssp. pulchellum (14) Allium carinatum ssp. pulchellum album (14)E Allium carolinianum (13)N Allium cernuum mix (14) E/N Allium cernuum “Dark Scape” (14)E Allium cernuum ‘Dwarf White” (14)E Allium cernuum ‘Pink Giant’ (14)N Allium cernuum x stellatum (14)E (received as cernuum , but it looks like a hybrid with stellatum, from SSE, OR KA A) Allium cernuum x stellatum (14)E (received as cernuum from a local garden centre) Allium clathratum (13) Allium crenulatum (13) Wild coll. -

Chemical Investigation of Devil's Club

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1939 Chemical investigation of devil's club Hubert William Murphy The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Murphy, Hubert William, "Chemical investigation of devil's club" (1939). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 6264. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/6264 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CHBMIOAL IMTESTIGATiaS Of D E W S CLDB by Hubert WlXlleoot Murphy B«8.# State UniTerslty of Montana, 1937 Presented In partial fulfillment of the re quirement for the d agree of Master of Selenee State Hhiversity of Montana 1939 Approved: 71 chairman of Boarct' of Examiners# Chairman of Coomittee on Graduate Study Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: EP37065 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI DiMtMUtior) PubliaNng UMI EP37065 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

Vegetables: Dark-Green Leafy, Deep Yellow, Dry Beans and Peas (Legumes), Starchy Vegetables and Other Vegetables1 Glenda L

Archival copy: for current recommendations see http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu or your local extension office. FCS 1055 Vegetables: Dark-Green Leafy, Deep Yellow, Dry Beans and Peas (legumes), Starchy Vegetables and Other Vegetables1 Glenda L. Warren2 • Deep yellow vegetables provide: Vitamin A. Eat 3 to 5 servings of vegetables each day. Examples: Carrots, pumpkins, sweet potatoes, Include all types of vegetables regularly. winter squash. What counts as one serving? • 1 cup of raw leafy vegetables (such as lettuce or spinach) • ½ cup of chopped raw vegetables • ½ cup of cooked vegetables • ¾ cup of vegetable juice Eat a variety of vegetables • Dry Beans and Peas (legumes) provide: It is important to eat many different vegetables. Thiamin, folic acid, iron, magnesium, All vegetables provide dietary fiber, some provide phosphorus, zinc, potassium, protein, starch, starch and protein, and they are also sources of fiber. Beans and peas can be used as meat many vitamins and minerals. alternatives since they are a source of protein. Examples: Black beans, black-eyed peas, • Dark-green vegetables provide: Vitamins A chickpeas (garbanzos), kidney beans, lentils, and C, riboflavin, folic acid, iron, calcium, lima beans (mature), mung beans, navy beans, magnesium, potassium. Examples: Beet pinto beans, split peas. greens, broccoli, collard greens, endive, • Starchy vegetables provide: Starch and escarole, kale, mustard greens, romaine varying amounts of certain vitamins and lettuce, spinach, turnip greens, watercress. minerals, such as niacin, vitamin B6, zinc, and 1. This document is FCS 1055, one of a series of the Department of Family, Youth and Community Sciences, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. -

CORRELATION BETWEEN METABOLITE PROFILE and PHYTOCHEMICAL CHARACTERISTICS of Ipomoea Aquatica Forssk

UNIVERSITI PUTRA MALAYSIA CORRELATION BETWEEN METABOLITE PROFILE AND PHYTOCHEMICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. WITH ITS ANTIOXIDANT AND α-GLUCOSIDASE INHIBITORY ACTIVITIES USING NMR-BASED METABOLOMICS UMAR LAWAL FSTM 2016 4 CORRELATION BETWEEN METABOLITE PROFILE AND PHYTOCHEMICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. WITH ITS ANTIOXIDANT AND α-GLUCOSIDASE INHIBITORY ACTIVITIES USING NMR-BASED METABOLOMICS UPM By UMAR LAWAL COPYRIGHT Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Universiti Putra Malaysia, in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy © March 2016 All material contained within the thesis, including without limitation text, logos, icons, photographs and all other artwork, is copyright material of Universiti Putra Malaysia unless otherwise stated. Use may be made of any material contained within the thesis for non-commercial purposes from the copyright holder. Commercial use of material may only be made with the express, prior, written permission of Universiti Putra Malaysia. Copyright © Universiti Putra Malaysia. UPM COPYRIGHT © DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my parents and family UPM COPYRIGHT © Abstract of thesis presented to the Senate of Universiti Putra Malaysia in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy CORRELATION BETWEEN METABOLITE PROFILE AND PHYTOCHEMICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. WITH ITS ANTIOXIDANT AND α-GLUCOSIDASE INHIBITORY ACTIVITIES USING NMR-BASED METABOLOMICS By UMAR LAWAL March 2016 UPM Chairman : Associate Professor Faridah Abas, PhD Faculty : Food Science and Technology Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. (morning glory) is a green leafy vegetable that is rich in minerals, proteins, vitamins, amino acids and secondary metabolites. The aims of the study were to discriminate Ipomoea extracts by 1H NMR spectroscopy in combination with chemometrics method and to determine their antioxidant and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities. -

Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, USDA § 319.56–2U

Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, USDA § 319.56–2u Country/locality Common name Botanical name Plant part(s) Tomato ....................................... (Lycopersicon esculentum) ........ Fruit, only if it is green upon arrival in the United States (pink or red fruit may only be imported from Alme- ria Province and only in accordance with § 319.56–2dd of this subpart). Watermelon ............................... Citrullus vulgaris ........................ Fruit, commercial ship- ments only. Suriname .................................... Amaranth ................................... Amaranthus spp ........................ Leaf and stem. Black palm nut ........................... Astrocaryum spp ........................ Fruit. Jessamine .................................. Cestrum latifolium ...................... Leaf and stem. Malabar spinach ........................ Bassella alba ............................. Leaf and stem. Mung bean ................................. Vigna radiata ............................. Seed sprout. Pak choi ..................................... Brassica chinensis ..................... Leaf and stem. Sweden ...................................... Dill .............................................. Anethum graveolens .................. Above ground parts. Taiwan ........................................ Bamboo ..................................... Bambuseae spp ......................... Edible shoot, free of leaves and roots. Burdock ...................................... Arctium lappa ............................ -

Brassica Rapa)Ssp

Li et al. Horticulture Research (2020) 7:212 Horticulture Research https://doi.org/10.1038/s41438-020-00449-z www.nature.com/hortres ARTICLE Open Access A chromosome-level reference genome of non- heading Chinese cabbage [Brassica campestris (syn. Brassica rapa)ssp. chinensis] Ying Li 1,Gao-FengLiu1,Li-MingMa2,Tong-KunLiu 1, Chang-Wei Zhang 1, Dong Xiao1, Hong-Kun Zheng2, Fei Chen1 and Xi-Lin Hou 1 Abstract Non-heading Chinese cabbage (NHCC) is an important leafy vegetable cultivated worldwide. Here, we report the first high-quality, chromosome-level genome of NHCC001 based on PacBio, Hi-C, and Illumina sequencing data. The assembled NHCC001 genome is 405.33 Mb in size with a contig N50 of 2.83 Mb and a scaffold N50 of 38.13 Mb. Approximately 53% of the assembled genome is composed of repetitive sequences, among which long terminal repeats (LTRs, 20.42% of the genome) are the most abundant. Using Hi-C data, 97.9% (396.83 Mb) of the sequences were assigned to 10 pseudochromosomes. Genome assessment showed that this B. rapa NHCC001 genome assembly is of better quality than other currently available B. rapa assemblies and that it contains 48,158 protein-coding genes, 99.56% of which are annotated in at least one functional database. Comparative genomic analysis confirmed that B. rapa NHCC001 underwent a whole-genome triplication (WGT) event shared with other Brassica species that occurred after the WGD events shared with Arabidopsis. Genes related to ascorbic acid metabolism showed little variation among the three B. rapa subspecies. The numbers of genes involved in glucosinolate biosynthesis and catabolism 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; were higher in NHCC001 than in Chiifu and Z1, due primarily to tandem duplication. -

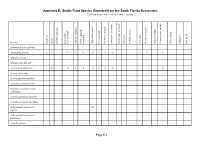

MSRP Appendix E

Appendix E. Exotic Plant Species Reported from the South Florida Ecosystem. Community types are indicated where known Species High Pine Scrub Scrubby high pine Beach dune/ Coastal strand Maritime hammock Mesic temperate hammock Tropical hardwood Pine rocklands Scrubby flatwoods Mesic pine flatwoods Hydric pine flatwoods Dry prairie Cutthroat grass Wet prairie Freshwater marsh Seepage swamp Flowing water swamp Pond swamp Mangrove Salt marsh Abelmoschus esculentus Abrus precatorius X X X X X X X X X X X X Abutilon hirtum Abutilon theophrasti Acacia auriculiformis X X X X X X X X X Acacia retinoides Acacia sphaerocephala Acalypha alopecuroidea Acalypha amentacea ssp. wilkesiana Acanthospermum australe Acanthospermum hispidum Achyranthes aspera var. X aspera Achyranthes aspera var. pubescens Acmella pilosa Page E-1 Species High Pine Scrub Scrubby high pine Beach dune/ Coastal strand Maritime hammock Mesic temperate hammock Tropical hardwood Pine rocklands Scrubby flatwoods Mesic pine flatwoods Hydric pine flatwoods Dry prairie Cutthroat grass Wet prairie Freshwater marsh Seepage swamp Flowing water swamp Pond swamp Mangrove Salt marsh Acrocomia aculeata X Adenanthera pavonina X X Adiantum anceps X Adiantum caudatum Adiantum trapeziforme X Agave americana Agave angustifolia cv. X marginata Agave desmettiana Agave sisalana X X X X X X Agdestis clematidea X Ageratum conyzoides Ageratum houstonianum Aglaonema commutatum var. maculatum Ailanthus altissima Albizia julibrissin Albizia lebbeck X X X X X X X Albizia lebbeckoides Albizia procera Page -

New Jan16.2011

Spring 2011 Mail Order Catalog Cistus Nursery 22711 NW Gillihan Road Sauvie Island, OR 97231 503.621.2233 phone 503.621.9657 fax order by phone 9 - 5 pst, visit 10am - 5pm, fax, mail, or email: [email protected] 24-7-365 www.cistus.com Spring 2011 Mail Order Catalog 2 USDA zone: 2 Symphoricarpos orbiculatus ‘Aureovariegatus’ coralberry Old fashioned deciduous coralberry with knock your socks off variegation - green leaves with creamy white edges. Pale white-tinted-pink, mid-summer flowers attract bees and butterflies and are followed by bird friendly, translucent, coral berries. To 6 ft or so in most any normal garden conditions - full sun to part shade with regular summer water. Frost hardy in USDA zone 2. $12 Caprifoliaceae USDA zone: 3 Athyrium filix-femina 'Frizelliae' Tatting fern An unique and striking fern with narrow fronds, only 1" wide and oddly bumpy along the sides as if beaded or ... tatted. Found originally in the Irish garden of Mrs. Frizell and loved for it quirkiness ever since. To only 1 ft tall x 2 ft wide and deciduous, coming back slowly in spring. Best in bright shade or shade where soil is rich. Requires summer water. Frost hardy to -40F, USDA zone 3 and said to be deer resistant. $14 Woodsiaceae USDA zone: 4 Aralia cordata 'Sun King' perennial spikenard The foliage is golden, often with red stems, and dazzling on this big and bold perennial, quickly to 3 ft tall and wide, first discovered in a department store in Japan by nurseryman Barry Yinger. Spikes of aralia type white flowers in summer are followed by purple-black berries.