Subandean and Adjacent Lowland Palm Communities in Bolivia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From “Invisible Natives” to an “Irruption of Indigenous Identity”? Two Decades of Change Among the Tacana in the Northern Bolivian Amazon

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Sondra Wentzel provided by Institutional Repository of the Ibero-American Institute, Berlin From “invisible natives” to an “irruption of indigenous identity”? Two decades of change among the Tacana in the northern Bolivian Amazon “Al final nos dimos cuenta todos que éramos tacanas” (Tacana leader 2001, quoted in Herrera 2009: 1). 1. Introduction: The Tacana In the mid 1980s, a time of redemocratization and structural adjustment policies in Bolivia, consultations about a region suitable for field research on the situation of indigenous peoples in the context of “Amazonian development” led me to the Province of Iturralde in the lowland north of the Department of La Paz (Figure 1). The culture of its indigenous inhabitants, the Tacana,1 had been documented by German researchers in the early 1950s (Hissink & Hahn 1961; 1984). Also, under the motto La Marcha al Norte, the region was the focus of large infrastructure and agro industrial projects which had already stimulated spontaneous colonization, but local people had little information about these activities nor support to defend their rights and interests. Between 1985 and 1988, I conducted about a year of village level field re- search in the region, mainly in Tumupasa, an ex-Franciscan mission among the Tacana founded in 1713 and transferred to its current location around 1770, San- ta Ana, a mixed community founded in 1971, and 25 de Mayo, a highland colonist cooperative whose members had settled between Tumupasa and Santa Ana from 1979 1 Tacana branch of the Pano-Tacanan language family, whose other current members are the Araona, Cavineño, Ese Ejja, and Reyesano (Maropa). -

Resumen …………………..……………………………………….…………..V Lista De Cuadros ………………………………………………………………Xi Lista De Figuras ………………………………………………………………..Xiii

UNIVERSIDAD MAYOR DE SAN ANDRÉS. FACULTAD DE AGRONOMÍA. CARRERA DE INGENIERIA AGRONÓMICA. TESIS DE GRADO COMPOSICIÓN FLORÍSTICA Y ESTRUCTURA DE UN BOSQUE MONTANO PLUVIAL EN DOS RANGOS ALTITUDINALES DE LAS SERRANÍAS DE PEÑALITO-NORESTE DE APOLO, ÁREA NATURAL DE MANEJO INTEGRADO MADIDI. (ANMI-MADIDI) Freddy Canqui Magne La Paz - Bolivia 2006 UNIVERSIDAD MAYOR DE SAN ANDRÉS. FACULTAD DE AGRONOMÍA. CARRERA DE INGENIERIA AGRONÓMICA. COMPOSICIÓN FLORÍSTICA Y ESTRUCTURA DE UN BOSQUE MONTANO PLUVIAL EN DOS RANGOS ALTITUDINALES DE LAS SERRANÍAS DE PEÑALITO-NORESTE DE APOLO, ÁREA NATURAL DE MANEJO INTEGRADO MADIDI. (ANMI-MADIDI) Tesis de Grado presentado como requisito parcial para optar el Título de Ingeniero Agrónomo. Freddy Canqui Magne Tutor: Ing. For. Luis Goitia Arze. .......................................................... Asesor: Ing. For. Alejandro Araujo Murakami. .......................................................... Comite Revisor: Ing. M. Sc. Félix Rojas Ponce. .......................................................... Ing. M. Sc. Wilfredo Peñafiel Rodríguez. .......................................................... Ing. Ramiro Mendoza Nogales. .......................................................... Decano: Ing. M. Sc. Jorge Pascuali Cabrera. ……………………………………….... DEDICATORIA: Dedicado al amor de mi abnegada madre Eugenia Magne Quispe y padre Francisco Canqui Aruni como a mis queridas hermanas Maria y Yola. AGRADECIMIENTOS Agradecer al supremo creador por darnos la vida y la naturaleza que nos cobija. Al Herbario Nacional de -

Diversity and Distributional Patterns of Aroids (Alismatales: Araceae) Along an Elevational Gradient in Darién, Panama

Webbia Journal of Plant Taxonomy and Geography ISSN: 0083-7792 (Print) 2169-4060 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tweb20 Diversity and distributional patterns of aroids (Alismatales: Araceae) along an elevational gradient in Darién, Panama Orlando O. Ortiz, María S. de Stapf & Thomas B. Croat To cite this article: Orlando O. Ortiz, María S. de Stapf & Thomas B. Croat (2019): Diversity and distributional patterns of aroids (Alismatales: Araceae) along an elevational gradient in Darién, Panama, Webbia, DOI: 10.1080/00837792.2019.1646465 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00837792.2019.1646465 View supplementary material Published online: 28 Aug 2019. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tweb20 WEBBIA https://doi.org/10.1080/00837792.2019.1646465 ARTICLE Diversity and distributional patterns of aroids (Alismatales: Araceae) along an elevational gradient in Darién, Panama Orlando O. Ortiz a, María S. de Stapfa,b and Thomas B. Croatc aHerbario PMA, Universidad de Panamá, Estafeta Universitaria, Panama City, Panama; bDepartamento de Botánica, Universidad de Panamá, Estafeta Universitaria, Panama City, Panama; cDepartment of Research (Monographs Section), Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY The family Araceae (aroids) represents an ecologically important and diverse group of plants in Received 24 May 2019 Panama, represented by 25 genera, 615 species, of which 277 (45%) are considered endemic. Accepted 18 July 2019 The aim of this study is to analyse the diversity and distributional patterns of aroids along an KEYWORDS fi elevation gradient in the species-rich forests of Darién, Panama. -

Women's Practices in Confronting Endemic Climate Variability in the Central Highlands of Bolivia

Wageningen University - Department of Social Sciences MSc Thesis Chair Group of Communication and Innovation Studies Women's Practices in Confronting Endemic Climate Variability in the Central Highlands of Bolivia October, 2011 Mariana Alem Zabalaga Supervisor: Dr. Stephen G. Sherwood Development and Rural Innovation Rural and Development MSc 1 Women´s Practices in Confronting Endemic Climate Variability in the Central Highlands of Bolivia MARIANA ALEM ZABALAGA 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I´d like to express my gratitude to the people from Chuñuchuñuni, authorities, men, woman and children, who opened me and Taira Isabela the doors of their community. With special regards, to Doña Virginia, Don Fortunato and Don Patricio that besides helping me to approach the community, they were the first ones sharing their trust and friendship with us, making my days in Chuñuchuñuni a great adventure and experience. I´d like to thank Fundación Agrecol Andes, with especial mention to Luis Carlos Aguilar that guided and taught me a lot during the whole thesis field work and internship. Also to thank the GRAC team, Alex Canviri for his good music and company during the field trips, to Tania Ricaldi from the Centro de Estudios Universitarios for her patience and inputs in the topic of research, to the tesistas of the Ayllu Urinsaya: Carolina Aguilar and Favio Fernandez for their great company and support during the field trips. I´d also like to thank the local NGOs with which I coordinated my field work for the thesis and to all their técnicos and engineers: I learnt a lot from all of you observing development projects in practice. -

Presentación

P PLAN DE DESARROLLO MUNICIPAL DE WALDO BALLIVIAN - TUMARAPI Pag. i PRESENTACIÓN Los bajos ingresos y la imposibilidad económica institucional de la Honorable Alcaldía Municipal Waldo Ballivián Tumarapi, para financiar la formulación del Plan de Desarrollo Municipal de la sexta sección de la provincia Pacajes, y así poder aplicar la Ley 1551 de Participación Popular que profundiza los procesos de la Descentralización hacia el nivel Municipal y la Ley 2028 Ley de Municipalidades en su art. 78, en la necesidad del Municipio de contar con este documento estratégico para los próximos cinco años, el Gobierno Municipal de Waldo Ballivián - Tumarapi mediante la firma de un convenio con el Servicio Departamental de Fortalecimiento Municipal y Comunitario (SED – FMC) de la Prefectura del Departamento de La Paz dentro el Proyecto de Potenciamiento a Gobiernos Municipales cuya finalidad es potenciar a los municipios mas pobres del Departamento a solicitud del Municipio Waldo Ballivián Tumarapi asume el SED FMC la responsabilidad de Formular el Plan de Desarrollo Municipal. En este contexto aplicando la guía de Planificación Participativa Municipal y la Estrategia de Desarrollo Económico Municipal (EDEM) se realizo la formulación del PDM, siendo responsabilidad del Gobierno Municipal de Waldo Ballivián - Tumarapi, ejecutar una gestión Técnico Administrativa eficiente y de los diferentes actores sociales en realizar el seguimiento y control social para una ejecución clara y trasparente de este Plan. Con estos antecedentes el componente de Formulación y Ajuste de PDM´s del SED – FMC presenta el Plan de Desarrollo Municipal (PDM) de Waldo - Tumarapi, este trabajo se da gracias a la participación plena de las OTB´s a través de la Planificación Participativa dando lugar a la priorización de sus demandas y encarar programas y proyectos para beneficio de cada una de sus comunidades para poder lograr un Municipio Productivo Competitivo. -

Journal of the International Palm Society Vol. 57(3) Sep. 2013 the INTERNATIONAL PALM SOCIETY, INC

Palms Journal of the International Palm Society Vol. 57(3) Sep. 2013 THE INTERNATIONAL PALM SOCIETY, INC. The International Palm Society Palms (formerly PRINCIPES) Journal of The International Palm Society Founder: Dent Smith The International Palm Society is a nonprofit corporation An illustrated, peer-reviewed quarterly devoted to engaged in the study of palms. The society is inter- information about palms and published in March, national in scope with worldwide membership, and the June, September and December by The International formation of regional or local chapters affiliated with the Palm Society Inc., 9300 Sandstone St., Austin, TX international society is encouraged. Please address all 78737-1135 USA. inquiries regarding membership or information about Editors: John Dransfield, Herbarium, Royal Botanic the society to The International Palm Society Inc., 9300 Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3AE, United Sandstone St., Austin, TX 78737-1135 USA, or by e-mail Kingdom, e-mail [email protected], tel. 44-20- to [email protected], fax 512-607-6468. 8332-5225, Fax 44-20-8332-5278. OFFICERS: Scott Zona, Dept. of Biological Sciences (OE 167), Florida International University, 11200 SW 8 Street, President: Leland Lai, 21480 Colina Drive, Topanga, Miami, Florida 33199 USA, e-mail [email protected], tel. California 90290 USA, e-mail [email protected], 1-305-348-1247, Fax 1-305-348-1986. tel. 1-310-383-2607. Associate Editor: Natalie Uhl, 228 Plant Science, Vice-Presidents: Jeff Brusseau, 1030 Heather Drive, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853 USA, e- Vista, California 92084 USA, e-mail mail [email protected], tel. 1-607-257-0885. -

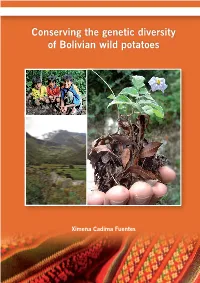

Phd Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, NL (2014) with References, with Summaries in Dutch, Spanish and English

Conserving the genetic diversity of Bolivian wild potatoes Ximena Cadima Fuentes Thesis committee Promotor Prof. Dr M.S.M. Sosef Professor of Biosystematics Wageningen University Co-promotors Dr R.G. van den Berg Associate professor, Biosystematics Group Wageningen University Dr R. van Treuren Researcher, Centre for Genetic Resources, the Netherlands (CGN) Wageningen University and Research Centre Other members Prof. Dr P.C. Struik, Wageningen University Prof. Dr J.C. Biesmeijer, Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden Dr M.J.M. Smulders, Wageningen University and Research Centre Dr S. de Haan, International Potato Centre, Lima, Peru This research was conducted under the auspices of the Graduate School of Experimental Plant Sciences. Conserving the genetic diversity of Bolivian wild potatoes Ximena Cadima Fuentes Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. Dr M.J. Kropff, in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Monday 8 December 2014 at 4 p.m. in the Aula. Ximena Cadima Fuentes Conserving the genetic diversity of Bolivian wild potatoes, 229 pages. PhD thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, NL (2014) With references, with summaries in Dutch, Spanish and English ISBN 978-94-6257-168-6 Biogeographic province Wild potato species Yungas Bolivian Puna Puna (800- Tucuman Mesophytic Xerophytic 4200 m) (500 (2300- (3200- 5000 m) 5200 m) 5200 m) Solanum acaule Bitter X X X S. achacachense Cárdenas X S. alandiae Cárdenas X S. arnezii Cárdenas X S. avilesii Hawkes & Hjrt. X S. berthaultii Hawkes X S. -

Seed Geometry in the Arecaceae

horticulturae Review Seed Geometry in the Arecaceae Diego Gutiérrez del Pozo 1, José Javier Martín-Gómez 2 , Ángel Tocino 3 and Emilio Cervantes 2,* 1 Departamento de Conservación y Manejo de Vida Silvestre (CYMVIS), Universidad Estatal Amazónica (UEA), Carretera Tena a Puyo Km. 44, Napo EC-150950, Ecuador; [email protected] 2 IRNASA-CSIC, Cordel de Merinas 40, E-37008 Salamanca, Spain; [email protected] 3 Departamento de Matemáticas, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Salamanca, Plaza de la Merced 1–4, 37008 Salamanca, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-923219606 Received: 31 August 2020; Accepted: 2 October 2020; Published: 7 October 2020 Abstract: Fruit and seed shape are important characteristics in taxonomy providing information on ecological, nutritional, and developmental aspects, but their application requires quantification. We propose a method for seed shape quantification based on the comparison of the bi-dimensional images of the seeds with geometric figures. J index is the percent of similarity of a seed image with a figure taken as a model. Models in shape quantification include geometrical figures (circle, ellipse, oval ::: ) and their derivatives, as well as other figures obtained as geometric representations of algebraic equations. The analysis is based on three sources: Published work, images available on the Internet, and seeds collected or stored in our collections. Some of the models here described are applied for the first time in seed morphology, like the superellipses, a group of bidimensional figures that represent well seed shape in species of the Calamoideae and Phoenix canariensis Hort. ex Chabaud. -

Plantas Utilizadas En Alimentación Humana Por Agricultores Mestizos Y Kichwas En Los Cantones Santa Clara, Mera Y Pastaza

Cultivos Tropicales, 2016, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 7-13 enero-marzo ISSN impreso: 0258-5936 Ministerio de Educación Superior. Cuba ISSN digital: 1819-4087 Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Agrícolas https://ediciones.inca.edu.cu PLANTAS UTILIZADAS EN ALIMENTACIÓN HUMANA POR AGRICULTORES MESTIZOS Y KICHWAS EN LOS CANTONES SANTA CLARA, MERA Y PASTAZA, PROVINCIA DE PASTAZA, ECUADOR Plants used in human feeding by half-breed and kichwa farmers in Santa Clara, Mera, Pastaza cantons, Pastaza province, Ecuador Ricardo V. Abril Saltos1), Tomás E. Ruiz Vásquez2, Jatnel Alonso Lazo2 y Janeth K. Aguinda Vargas1 ABSTRACT. This research was conducted in the Pastaza RESUMEN. Esta investigación se realizó en la provincia de province, Ecuador, its aim was identify the main species Pastaza, Ecuador, su objetivo fue identificar las principales used for human consumption on farms of Pastaza, Mera and especies vegetales utilizadas en alimentación humana, en las Santa Clara cantons, comparing their reporting frequency explotaciones agropecuarias de los cantones Pastaza, Mera y depending on the canton and producer ethnia, for which a Santa Clara, comparando su frecuencia de reporte en función del survey, consisting of aspects of identification of farmers, cantón y etnia del productor, para lo cual se elaboró una encuesta, plants used in human food and ways of uses, which was que consta de aspectos de identificación de los agricultores, applied to 214 producers in the province, corresponding plantas utilizadas en alimentación humana y sus formas de to 30 % of producers identified was developed. Globally, usos, la cual fue aplicada a 214 productores en la provincia, 59 species were reported by canton bearing 32 species in correspondiente al 30 % de productores identificados. -

Lista De Flora.Xlsx

Familia Genero Especie Nombre Científico GUI Ecuador Alismataceae Echinodorus berteroi Echinodorus berteroi ec.bio.pla.4752 1 Alismataceae Echinodorus bolivianus Echinodorus bolivianus ec.bio.pla.4753 1 Alismataceae Echinodorus bracteatus Echinodorus bracteatus ec.bio.pla.4754 1 Alismataceae Echinodorus eglandulosus Echinodorus eglandulosus ec.bio.pla.4755 1 Alismataceae Echinodorus grisebachii Echinodorus grisebachii ec.bio.pla.4758 1 Alismataceae Echinodorus horizontalis Echinodorus horizontalis ec.bio.pla.4759 1 Alismataceae Echinodorus paniculatus Echinodorus paniculatus ec.bio.pla.4762 1 Alismataceae Echinodorus tunicatus Echinodorus tunicatus ec.bio.pla.4763 1 Alismataceae Hydrocleys nymphoides Hydrocleys nymphoides ec.bio.pla.4765 1 Alismataceae Limnocharis flava Limnocharis flava ec.bio.pla.4768 1 Alismataceae Limnocharis laforestii Limnocharis laforestii ec.bio.pla.4769 1 Alismataceae Sagittaria guayanensis Sagittaria guayanensis ec.bio.pla.4770 1 Alismataceae Sagittaria lancifolia Sagittaria lancifolia ec.bio.pla.4771 1 Alismataceae Sagittaria latifolia Sagittaria latifolia ec.bio.pla.4772 1 Alismataceae Sagittaria montevidensis Sagittaria montevidensis ec.bio.pla.4773 1 Araceae Alocasia cucullata Alocasia cucullata ec.bio.pla.4774 1 Araceae Alocasia macrorrhizos Alocasia macrorrhizos ec.bio.pla.4776 1 Araceae Anthurium acutissimum Anthurium acutissimum ec.bio.pla.4784 1 Araceae Anthurium albidum Anthurium albidum ec.bio.pla.4788 1 Araceae Anthurium albispatha Anthurium albispatha ec.bio.pla.4789 1 Araceae Anthurium albovirescens -

FLORA of the GUIANAS New York, November 2017

FLORA OF THE GUIANAS NEWSLETTER N° 20 SPECIAL WORKSHOP ISSUE New York, November 2017 FLORA OF THE GUIANAS NEWSLETTER N° 20 SPECIAL WORKSHOP ISSUE Flora of the Guianas (FOG) Meeting and Seminars and Scientific symposium “Advances in Neotropical Plant Systematics and Floristics,” New York, 1–3 November 2017 The Flora of the Guianas is a co-operative programme of: Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Belém; Botanischer Garten und Botanisches Museum Berlin-Dahlem, Berlin; Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, IRD, Centre de Cayenne, Cayenne; Department of Biology, University of Guyana, Georgetown; Herbarium, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; New York Botanical Garden, New York; Nationaal Herbarium Suriname, Paramaribo; Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris; Nationaal Herbarium Nederland, Utrecht University branch, Utrecht, and Department of Botany, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. For further information see the website: http://portal.cybertaxonomy.org/flora-guianas/ Published on April 2019 Flora of the Guianas Newsletter No. 20. Compiled and edited by B. Torke New York Botanical Garden, New York, USA 2 CONTENTS 1. SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................... 5 2. MEETING PROGRAM .................................................................................................... 5 3. SYMPOSIUM PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS ............................................................... 7 4. MINUTES OF THE ADVISORY BOARD MEETING .................................................... -

Plant Names Catalog 2013 1

Plant Names Catalog 2013 NAME COMMON NAME FAMILY PLOT Abildgaardia ovata flatspike sedge CYPERACEAE Plot 97b Acacia choriophylla cinnecord FABACEAE Plot 199:Plot 19b:Plot 50 Acacia cornigera bull-horn acacia FABACEAE Plot 50 Acacia farnesiana sweet acacia FABACEAE Plot 153a Acacia huarango FABACEAE Plot 153b Acacia macracantha steel acacia FABACEAE Plot 164 Plot 176a:Plot 176b:Plot 3a:Plot Acacia pinetorum pineland acacia FABACEAE 97b Acacia sp. FABACEAE Plot 57a Acacia tortuosa poponax FABACEAE Plot 3a Acalypha hispida chenille plant EUPHORBIACEAE Plot 4:Plot 41a Acalypha hispida 'Alba' white chenille plant EUPHORBIACEAE Plot 4 Acalypha 'Inferno' EUPHORBIACEAE Plot 41a Acalypha siamensis EUPHORBIACEAE Plot 50 'Firestorm' Acalypha siamensis EUPHORBIACEAE Plot 50 'Kilauea' Acalypha sp. EUPHORBIACEAE Plot 138b Acanthocereus sp. CACTACEAE Plot 138a:Plot 164 Acanthocereus barbed wire cereus CACTACEAE Plot 199 tetragonus Acanthophoenix rubra ARECACEAE Plot 149:Plot 71c Acanthus sp. ACANTHACEAE Plot 50 Acer rubrum red maple ACERACEAE Plot 64 Acnistus arborescens wild tree tobacco SOLANACEAE Plot 128a:Plot 143 1 Plant Names Catalog 2013 NAME COMMON NAME FAMILY PLOT Plot 121:Plot 161:Plot 204:Plot paurotis 61:Plot 62:Plot 67:Plot 69:Plot Acoelorrhaphe wrightii ARECACEAE palm:Everglades palm 71a:Plot 72:Plot 76:Plot 78:Plot 81 Acrocarpus fraxinifolius shingle tree:pink cedar FABACEAE Plot 131:Plot 133:Plot 152 Acrocomia aculeata gru-gru ARECACEAE Plot 102:Plot 169 Acrocomia crispa ARECACEAE Plot 101b:Plot 102 Acrostichum aureum golden leather fern ADIANTACEAE Plot 203 Acrostichum Plot 195:Plot 204:Plot 3b:Plot leather fern ADIANTACEAE danaeifolium 63:Plot 69 Actephila ovalis PHYLLANTHACEAE Plot 151 Actinorhytis calapparia calappa palm ARECACEAE Plot 132:Plot 71c Adansonia digitata baobab MALVACEAE Plot 112:Plot 153b:Plot 3b Adansonia fony var.