Youth Employability Scoping Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Library of Garrick Lee Praise for up and out of Poverty

ptg From the Library of Garrick Lee Praise for Up and Out of Poverty “Philip Kotler, pioneer in social marketing, and Nancy Lee bring their inci- sive thinking and pragmatic approach to the problems of behavior change at the bottom of the pyramid. Creative solutions to persistent problems that affect the poor require the tools of social marketing and multi-stakeholder management. In this book, the poor around the world have found new and powerful allies. A must read for those who work to alleviate poverty and restore human dignity.” —CK Prahalad, Paul and Ruth McCracken Distinguished University Pro- fessor, Ross School of Business, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; and author of The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid, 5th Anniversary Edition “Up and Out of Poverty will prove very helpful to antipoverty planners and workers to help the poor deal better with their problems of daily living. Philip Kotler and Nancy Lee illustrate vivid cases of how the poor can be helped by social marketing solutions.” —Mechai Viravaidya, founder and Chairman, ptg Population and Community Development Association, Thailand “Helping others out of poverty is a simple task; yet it remains incomplete. Putting poverty in a museum is achievable within a short span of time—if we all work together, we can do it!” —Muhammad Yunus, winner of the Nobel Prize for Peace; and Managing Director, Grameen Bank “In Up and Out of Poverty, Kotler and Lee remind us that ‘markets’ are peo- ple. A series of remarkable case studies demonstrate conclusively the power of social marketing to release the creative energy of people to solve their own problems. -

The Privatization of Poverty Alleviation Mechai Viravaidya Paper Prepared

The Privatization of Poverty Alleviation Mechai Viravaidya Paper prepared for presentation at the “Prosper or Perish: Asian Poverty and the Australian Economy” conference conducted by the Crawford Fund for International Agricultural Research, Parliament House, Canberra, Australia, June 28, 2001 Copyright 2001 by Mechai Viravaidya. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies. The Privatization of Poverty Alleviation ASIAN ADDRESS MECHAI VIRAVAIDYA While many developing country governments have been able to significantly improve basic infrastructure such as roads, electricity, schools and health centres, they have failed to make much progress in poverty alleviation in rural areas. The people employed in this endeavour have been the wrong type and the methods used have been incorrect. Simply put, we have used the wrong doctor as well as the wrong medicine; no wonder the patient is still sick! Let us take a look where we went wrong. In a typical developing country, what are the poorest doing to earn an income? Some pick up garbage and sell it, some buy rice, cook it and sell it. Some grow vegetables or fruit, raise chickens and sell their produce. They are all engaged in business. A reasonable question would be, why are they poor? The answer is that they are poor because they are not very good at business and they lack or are denied opportunity. If this is the diagnosis, the task to remedy the situation should be to provide them with opportunity through particular loans or credit, and to assist them to learn to be better at business. -

Thailand's Best Practices and Lessons Learned in Development Volume 1

1 Thailand’s Best Practices and Lessons Learned in Development Volume 1 Thailand’s Best Practices and Lessons Learned in Development 1 Foreword Thailand has made remarkable progress in the fields of social and economic development in recent decades, which enabled Thailand to become a middle-income country. According to the first Thailand Millennium Development Goals Report, 2004, Thailand has already reached almost all targets set in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Therefore, Thailand has set more ambitious targets, called MDG Plus, that go well beyond the internationally agreed MDG targets. The development examples of many innovative projects under the royal patronage of His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej are particularly valuable, and His Majesty’s philosophy on “Sufficiency Economy” has become a key principle in Thailand’s national development plan and practices. As Thailand succeeded in its development during the past four decades, The Royal Thai Government has shared its knowledge and experiences with other developing countries, especially its neighbors in the Greater Mekong Sub-Region (GMS), through technical cooperation and human resource development. Helping the development of neighboring countries is among the highest priorities of Thai foreign policy. This has led to Thailand becoming a training and resource center for development, especially for scholars and practitioners from other developing countries. The Thailand International Development Cooperation Agency (TICA) of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is the main Government’s coordinating body for technical and development assistance, including managing Thailand’s Official Development Assistance (ODA). Working closely with TICA and supporting Thailand as an active donor of the South is the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in Thailand. -

Adoption and Diffusion Theories Used in Thailand's Family Planning Program Heather Jill Rutz Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1989 Adoption and diffusion theories used in Thailand's family planning program Heather Jill Rutz Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Demography, Population, and Ecology Commons, and the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons Recommended Citation Rutz, Heather Jill, "Adoption and diffusion theories used in Thailand's family planning program" (1989). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 17305. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/17305 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Adoption and diffusion theories used in Thailand's family planning program by Heather Jill Rutz A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF COMMUNITY AND REGIONAL PLANNING Major: community and Regional Planning Signatures have been redacted for privacy ~uwa ~~a~e university Ames, Iowa 1989 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 World Population Growth 1 Movement to Slow Population Growth 3 population Growth Theories 5 Supply and Demand 8 Why Thailand 9 Hypothesis 11 Research Approach 12 CHAPTER II. LITERATURE REVIEW 14 Review of Adoption and Diffusion Theories 14 Adoption Perspective 21 Market and Infrastructure Perspective 28 Summary 34 CHAPTER III. THAILAND 36 Characteristics of Thailand 36 Population Growth 38 History of Family Planning in Thailand 41 Private Organizations' Efforts in Family Planning 47 Women and Cultural Factors in Thailand 51 CHAPTER IV. -

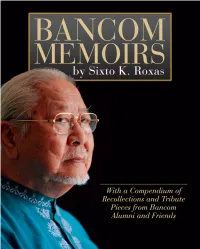

With a Compendium of Recollections and Tribute Pieces from Bancom Alumni and Friends

The ebook version of this book may be downloaded at www.xBancom.com This Bancom book project was made possible by the generous support of mr. manuel V. Pangilinan. The book launching was sponsored by smart infinity copyright © 2013 by sixto K. roxas Bancom memoirsby sixto K. roxas With a Compendium of Recollections and Tribute Pieces from Bancom Alumni and Friends Edited by eduardo a. Yotoko Published by PLDT-smart Foundation, inc and Bancom alumni, inc. (BaLi) contents Foreword by Evelyn R. Singson 5 Foreword by Francis G. Estrada 7 Preface 9 Prologue: Bancom and the Philippine financial markets 13 chapter 1 Bancom at its 10th year 24 chapter 2 BTco and cBTc, Bliss and Barcelon 28 chapter 3 ripe for investment banking 34 chapter 4 Founding eDF 41 chapter 5 organizing PDcP 44 chapter 6 childhood, ateneo and social action 48 chapter 7 my development as an economist 55 chapter 8 Practicing economics at central Bank and PnB 59 chapter 9 corporate finance at Filoil 63 chapter 10 economic planning under macapagal 71 chapter 11 shaping the development vision 76 chapter 12 entering the money market 84 chapter 13 creating the Treasury Bill market 88 chapter 14 advising on external debt management 90 chapter 15 Forming a virtual merchant bank 103 chapter 16 Functional merger with rcBc 108 chapter 17 asean merchant banking network 112 chapter 18 some key asian central bankers 117 chapter 19 asia’s star economic planners 122 chapter 20 my american express interlude 126 chapter 21 radical reorganization and BiHL 136 chapter 22 Dewey Dee and the end of Bancom 141 chapter 23 The total development company components 143 chapter 24 a changed life-world 156 chapter 25 The sustainable development movement 167 chapter 26 The Bancom university of experience 174 chapter 27 summing up the legacy 186 Photo Folio 198 compendium of recollections and Tribute Pieces from Bancom alumni and Friends 205 4 Bancom memoirs Bancom was absorbed by union Bank in 1981. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Stuck in Traffic: Sexual Politics and Criminal Injustice in Social Movements Against Human Trafficking Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4115c8f8 Author Kinney, Edith Celine Marie Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Stuck in Traffic: Sexual Politics and Criminal Injustice in Social Movements Against Human Trafficking By Edith Celine Marie Kinney A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Jurisprudence & Social Policy in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kristin Luker, Chair Professor Jonathan Simon Professor Kathy Abrams Professor Marianne Constable Fall 2011 Abstract Stuck in Traffic: Sexual Politics and Criminal Injustice in Social Movements Against Human Trafficking by Edith Celine Marie Kinney Doctor of Philosophy in Jurisprudence & Social Policy University of California, Berkeley Professor Kristin Luker, Chair This dissertation analyzes the sexual politics of transnational movements against human trafficking. I track the periodic securitization of women’s migration and commercial sexual exploitation in international affairs from the Victorian-era movement against “White Slavery” to the contemporary campaign against “modern day slavery” and sex trafficking, using the case of Thailand to investigate the role of women’s advocates in the transformation of governance strategies to address the issue. Drawing on a year of field research in Thailand, I analyze the development of collaborative, inter-agency organizations that partner non-governmental organization (“NGO”) advocates with criminal justice and social welfare officials to implement “rights-based” measures to prevent trafficking, protect victims, and prosecute offenders. -

Bill Gates Sr. Trip to Thailand - November 29, 2010 - Highlights

Population & Community Development Association Bill Gates Sr. Trip to Thailand - November 29, 2010 - Highlights Thailand had the honor of hosting Mr. William Howard Gates Sr., Co-Chair of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and Mimi Gardner Gates., his wife. Mr. and Mrs. Gates visited our office and the Cabbages & Condoms Restaurant in Bangkok. They also met with villagers from the Village Development Partnership program, a women’s silk- weaving group from Buriram Province, a garland-making group from the Grand Palace, and students from international and Thai schools (including our own Mechai Pattana School) involved in the Youth Philanthropy program. Following this greeting session, Mechai Viravaidya presented Mr. and Mrs. Gates with information on our initiatives in family planning, HIV/AIDS prevention, poverty eradication, education, youth philanthropy, and ongoing cooperation with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. We hosted the team for a luncheon at Cabbages & Condoms. Since, the date was close to World AIDS day, Mr. and Mrs. Gates graciously accepted our small gift of condom caps, so that they could highlight the renewed effort towards HIV prevention worldwide. In the afternoon, the Mechai Viravaidya Foundation organized a “High Tea Discussion and Q&A with Bill Gates Sr.” at the Plaza Athenee Hotel, where he discussed with approximately 100 senior business and civil society leaders from Southeast Asia the importance of philanthropy and strategies to improve effectiveness in their giving. Some of the key quotes from Mr. Gates included: On having Bill Gates Jr. as a son “I’ve had more than one good thing happen to me in my life, but no one thing that exceeds my joy from what’s happened to my son. -

Pdf, Accessed April 19, 2014

http://englishkyoto-seas.org/ View the table of contents for this issue: http://englishkyoto-seas.org/2016/04/vol-5-no-1-of-southeast-asian-studies/ Subscriptions: http://englishkyoto-seas.org/mailing-list/ For permissions, please send an e-mail to: [email protected] SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES Vol. 5, No. 1 April 2016 CONTENTS Political Networks in Asia Guest Editors: ONIMARU Takeshi and KHOO Boo Teik KHOO Boo Teik Introduction: A Place for Networks in Asian Politics ..............................(3) ONIMARU Takeshi PASUK Phongpaichit Very Distinguished Alumni: Thai Political Networking .......................(19) NUALNOI Treerat Chris BAKER Teresa S. The Rise and Fall of Virata’s Network: Technocracy and Encarnacion TADEM the Politics of Economic Decision Making in the Philippines ...............................................................................................................(35) KHOO Boo Teik Networks in Pursuit of a “Two-Coalition System” in Malaysia: Pakatan Rakyat’s Mobilization of Dissent between Reformasi and the Tsunami ..................................................................................(73) NARUEMON Thabchumpon Contending Political Networks: A Study of the “Yellow Shirts” and “Red Shirts” in Thailand’s Politics ..............................................(93) ONIMARU Takeshi Shanghai Connection: The Construction and Collapse of the Comintern Network in East and Southeast Asia ......................(115) MIICHI Ken Looking at Links and Nodes: How Jihadists in Indonesia Survived .............................................................................................................(135) -

Innovative Partners 1 Innovative Partners

I N N OVAT I V E PARTNERS The Rockefeller Foundation and Thailand the rockefeller foundation centennial series Innovative Partners 1 innovative partners the rockefeller foundation and thailand By William H. Becker, Ph.D. Innovation for the Next 100 Years Rockefeller Foundation Centennial Series Preface from Dr. Judith Rodin 22 Foreword – Prawase Wasi, M.D. 24 Introduction 28 1 Fighting Hookworm, 42 Promoting Public Health © 2013 by Rockefeller Foundation Images held by the Rockefeller Archive The Rockefeller Foundation Centennial Series Center have been deemed to be owned 11 The Prince, the Foundation, 62 All rights reserved. Books published in the Rockefeller by the Rockefeller Foundation unless Foundation Centennial Series provide we were able to determine otherwise. and the Transformation of Cover: case studies for people around the Specific permission has been granted Top: Dissecting room, world who are working “to promote the by the copyright holder to use the Medical Education Chulalongkorn University (1930). well-being of humankind.” Three books following works: Rockefeller Archive Center. highlight lessons learned in the fields Bottom: Boats along the of agriculture, health, and philanthropy. Steve McCurry: 6-7, 10-11 Mekong River near Mukdahan (2009). Three others explore the Foundation’s Harvard University Archives, 67 111 Thailand and the Green Revolution 88 Patrick de Noirmont. work in Africa, Thailand, and the United Patrick de Noirmont: 2-3, 14-15, 18-19, States. For more information about 60-61, 85, 86-87, 104-105, 109, 148-149, the Rockefeller Foundation Centennial Book design by Pentagram. 150-151, 154-155, 158, 161, 166-167, 172, initiatives, visit www.centennial. -

2014 Ramon Magsaysay Awardees Announced

31 July 2014 PRESS RELEASE 2014 Ramon Magsaysay Awardees Announced The Board of Trustees of the Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation (RMAF) today announced that this year five individuals and one organization from Afghanistan, China, Indonesia, Pakistan, and the Philippines will receive Asia’s premier prize, the Ramon Magsaysay Award. The 2014 Awardees are: Hu Shuli, from China. She is being recognized for “her unrelenting commitment to truthful, relevant, and unassailable journalism, her fearless promotion of transparency and accountability in business and public governance, and her leadership in blazing the way for more professional and independent-minded media practices in China.” Saur Marlina Manurung, from Indonesia. She is being recognized for “her ennobling passion to protect and improve the lives of Indonesia’s forest people, and her energizing leadership of volunteers in SOKOLA’s customized education program that is sensitive to the lifeways of indigenous communities and the unique development challenges they face.” Omara Khan Masoudi, from Afghanistan. He is being recognized for “his courage, labor, and leadership in protecting Afghan cultural heritage, rebuilding an institution vital for Afghanistan’s future, and reminding his countrymen and peoples everywhere that in recognizing humanity’s shared patrimony, we can be inspired to stand together in peace.” The Citizens Foundation, from Pakistan. The organization is being recognized for “the social vision and high-level professionalism of its founders and those who run its schools, in successfully pursuing their conviction that, with sustained civic responsiveness, quality education made available to all—irrespective of religion, gender, or economic status—is the key to Pakistan’s brighter future.” Wang Canfa, from China. -

Mechai Viravaidya (LLD)

Wednesday 18 January (3pm) Mechai Viravaidya (LLD) Mr Vice-Chancellor. At ceremonies such as this, it’s commonplace to announce people with the most grandiose of titles. One minute we’re addressing a Baron, the next we’re introducing a former Archbishop to the audience. Nevertheless, I am confident this is first time we have had the privilege of introducing someone internationally known as…Mr Condom. It’s certainly an unusual moniker, but is one earned through the most inspirational of methods. At Warwick, we want our people to make a positive impact in the world. Today, we honour someone whose positive impact in the field of public health changed a whole nation. Thailand can be grateful for the efforts of its Mr Condom: Mechai Viravaidya. Mechai, who was born in Bangkok just over [76] years ago, is the son of two doctors who both believed it was right they should help the poor. These values were passed down to Mechai, who studied Commerce at the University of Melbourne before returning to Thailand. He worked as an economist, evaluating the government’s development programmes. It was at this time Mechai fully appreciated the challenge facing Thailand. By the mid-1970s, rural women in Thailand were having approximately seven children per family. The country was gripped by poverty. As Mechai himself said, “What hit me was that there was no way schools and doctors could keep up with the birth rate.” So Mechai took it upon himself to find a way. In 1974, he founded the Population and Community Development Association. -

Stuck in Traffic: Sexual Politics and Criminal Injustice in Social Movements Against Human Trafficking

Stuck in Traffic: Sexual Politics and Criminal Injustice in Social Movements Against Human Trafficking By Edith Celine Marie Kinney A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Jurisprudence & Social Policy in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kristin Luker, Chair Professor Jonathan Simon Professor Kathy Abrams Professor Marianne Constable Fall 2011 Abstract Stuck in Traffic: Sexual Politics and Criminal Injustice in Social Movements Against Human Trafficking by Edith Celine Marie Kinney Doctor of Philosophy in Jurisprudence & Social Policy University of California, Berkeley Professor Kristin Luker, Chair This dissertation analyzes the sexual politics of transnational movements against human trafficking. I track the periodic securitization of women’s migration and commercial sexual exploitation in international affairs from the Victorian-era movement against “White Slavery” to the contemporary campaign against “modern day slavery” and sex trafficking, using the case of Thailand to investigate the role of women’s advocates in the transformation of governance strategies to address the issue. Drawing on a year of field research in Thailand, I analyze the development of collaborative, inter-agency organizations that partner non-governmental organization (“NGO”) advocates with criminal justice and social welfare officials to implement “rights-based” measures to prevent trafficking, protect victims, and prosecute offenders. I examine the rise of the anti-trafficking movement in Thailand to explore the complex interplay between the state, civil society organizations, and transnational advocacy networks, as well as movement organizations’ strategic mobilization of domestic and international law to pressure states for policy reform.