Download Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ratchaburi Ratchaburi Ratchaburi

Ratchaburi Ratchaburi Ratchaburi Dragon Jar 4 Ratchaburi CONTENTS HOW TO GET THERE 7 ATTRACTIONS 9 Amphoe Mueang Ratchaburi 9 Amphoe Pak Tho 16 Amphoe Wat Phleng 16 Amphoe Damnoen Saduak 18 Amphoe Bang Phae 21 Amphoe Ban Pong 22 Amphoe Photharam 25 Amphoe Chom Bueng 30 Amphoe Suan Phueng 33 Amphoe Ban Kha 37 EVENTS & FESTIVALS 38 LOCAL PRODUCTS & SOUVENIRS 39 INTERESTING ACTIVITIS 43 Cruising along King Rama V’s Route 43 Driving Route 43 Homestay 43 SUGGEST TOUR PROGRAMMES 44 TRAVEL TIPS 45 FACILITIES IN RATCHABURI 45 Accommodations 45 Restaurants 50 Local Product & Souvenir Shops 54 Golf Courses 55 USEFUL CALLS 56 Floating Market Ratchaburi Ratchaburi is the land of the Mae Klong Basin Samut Songkhram, Nakhon civilization with the foggy Tanao Si Mountains. Pathom It is one province in the west of central Thailand West borders with Myanmar which is full of various geographical features; for example, the low-lying land along the fertile Mae Klong Basin, fields, and Tanao Si Mountains HOW TO GET THERE: which lie in to east stretching to meet the By Car: Thailand-Myanmar border. - Old route: Take Phetchakasem Road or High- From legend and historical evidence, it is way 4, passing Bang Khae-Om Noi–Om Yai– assumed that Ratchaburi used to be one of the Nakhon Chai Si–Nakhon Pathom–Ratchaburi. civilized kingdoms of Suvarnabhumi in the past, - New route: Take Highway 338, from Bangkok– from the reign of the Great King Asoka of India, Phutthamonthon–Nakhon Chai Si and turn into who announced the Lord Buddha’s teachings Phetchakasem Road near Amphoe Nakhon through this land around 325 B.C. -

Republic of the Philippines PROVINCE of ZAMBOANGA DEL NORTE Municipality of President Manuel A

Republic of the Philippines PROVINCE OF ZAMBOANGA DEL NORTE Municipality of President Manuel A. Roxas OFFICE OF THE SANGGUNIANG BAYAN EXCERPT FROM THE MINUTES OF THE REGULAR SESSION OF THE SANGGUNIANG BAYANOF PRESIDENT MANUEL A. ROXAS, ZAMBOANGA DEL NORTE HELD ATTHE ROXAS MUNICIPAL SESSION HALL ON FEBRUARY 19, 2018 PRESENT: Hon. Leonor O. Alberto, Municipal Vice Mayor/ Presiding Officer Hon. Ismael A. Rengquijo, Jr., SB Member/ Floor Leader Hon. Clayford C. Vailoces, SB Member/ 1st Asst. Floor Leader Hon. Lucilito C. Bael, Member Hon. Glicerio E. Cabus, Jr., SB Member Hon. Mark Julius C. Ybanez, SB Member/ President Pro Tempore Hon. Librado C. Magcanta, Sr., SB Member/ 2nd Asst. Floor Leader Hon. Helen L. Bruce, SB Member Hon. Reynaldo G. Abitona, SB Member Hon. Angelita L. Rengquijo, ABC President/ SB Member ABSENT: None “RESOLUTION NO. 68 Series 2018 RESOLUTION AUTHORIZING THE MUNICIPAL MAYOR TO INTERPOSE NO OBJECTION FOR THE PRE PATENT APPLICATION OF THE BARANGAY COUNCIL OF DOHINOB RELATIVE TO THE DEAD ROAD LOCATED AT BARANGAY DOHINOB, THIS MUNICIPALITY WHEREAS, received by the Office of the Sangguniang Bayan was Resolution No. 5, series 2018 of the Barangay Council of Dohinob requesting this Body to interpose no objection of their free patent application on a dead road; WHEREAS, said resolution was referred to the Committee on Laws and based on its findings under Committee Report No. 2018-12 conducted on February 15, 2018, it was recommended to the Sangguniang Bayan to authorize the Municipal Mayor for the aforementioned purpose/s; WHEREFORE, viewed from the foregoing, and On motion of Hon. Clayford C. -

Sukhothai Phitsanulok Phetchabun Sukhothai Historical Park CONTENTS

UttaraditSukhothai Phitsanulok Phetchabun Sukhothai Historical Park CONTENTS SUKHOTHAI 8 City Attractions 9 Special Events 21 Local Products 22 How to Get There 22 UTTARADIT 24 City Attractions 25 Out-Of-City Attractions 25 Special Events 29 Local Products 29 How to Get There 29 PHITSANULOK 30 City Attractions 31 Out-Of-City Attractions 33 Special Events 36 Local Products 36 How to Get There 36 PHETCHABUN 38 City Attractions 39 Out-Of-City Attractions 39 Special Events 41 Local Products 43 How to Get There 43 Sukhothai Sukhothai Uttaradit Phitsanulok Phetchabun Phra Achana, , Wat Si Chum SUKHOTHAI Sukhothai is located on the lower edge of the northern region, with the provincial capital situated some 450 kms. north of Bangkok and some 350 kms. south of Chiang Mai. The province covers an area of 6,596 sq. kms. and is above all noted as the centre of the legendary Kingdom of Sukhothai, with major historical remains at Sukhothai and Si Satchanalai. Its main natural attraction is Ramkhamhaeng National Park, which is also known as ‘Khao Luang’. The provincial capital, sometimes called New Sukhothai, is a small town lying on the Yom River whose main business is serving tourists who visit the Sangkhalok Museum nearby Sukhothai Historical Park. CITY ATTRACTIONS Ramkhamhaeng National Park (Khao Luang) Phra Mae Ya Shrine Covering the area of Amphoe Ban Dan Lan Situated in front of the City Hall, the Shrine Hoi, Amphoe Khiri Mat, and Amphoe Mueang houses the Phra Mae Ya figure, in ancient of Sukhothai Province, this park is a natural queen’s dress, said to have been made by King park with historical significance. -

Rights of Refugees and Migrant Workers

The Survey of Thai Public Opinion toward Myanmar Refugees and Migrant Workers: A Case Study of Ratchaburi Province Malee Sunpuwan Sakkarin Niyomsilpa Institute for Population and Social Research, Mahidol University Supported by the World Health Organization and the European Union The Survey of Thai Public Opinion toward Myanmar Refugees and Migrant Workers: A Case Study of Ratchaburi Province Malee Sunpuwan Sakkarin Niyomsilpa @Copyright 2014 by the Institute for Population and Social Research, Mahidol University All rights reserved 500 copies Cataloguing in Publication The Survey of Thai Public Opinion toward Myanmar Refugees and Migrant Workers: A Case Study of Ratchaburi Province / Malee Sunpuwan, Sakkarin Niyomsilpa. -- 1st ed. -- Nakhon Pathom: Institute for Population and Social Research, Mahidol University, 2014 (Publication/ Institute for Population and Social Research, Mahidol University; no. 432) ISBN 978-616-279-493-3 1. Public opinion. 2. Public opinion -- Myanmar. 3. Migrant labor -- Myanmar. 4. Refugees -- Burma. I. Malee Sunpuwan. II. Sakkarin Niyomsilpa. III. Mahidol University. Institute for Population and Social Research. IV. Series. HN90.P8 S963r 2014 Published by: Institute for Population and Social Research, Mahidol University Phutthamonthon 4 Road, Salaya, Phutthamonthon, Nakhon Pathom 73170 Telephone: 66 2 441 0201-4 Fax: 66 2 441 9333 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.ipsr.mahidol.ac.th IPSR Publication No. 432 PREFACE i PREFACE Refugees are people who are victims of forced migration. Since ethnic conflicts and fighting between government forces and minority groups in Myanmar have been occurring during the past few decades, hundreds of thousands of people have been forced to leave their homes and villages, looking for safe areas elsewhere. -

The Lady L Story Research Vol

Asia Pacific Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, Vol. 4, No. 2, May 2016 _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Asia Pacific Journal of A Life Dedicated to Public Service: Multidisciplinary The Lady L Story Research Vol. 4 No.2, 37-43 Maribeth P. Bentillo1, Ericka Alexis A. Cortes2,Jlayda Carmel Y. Gabor3, May 2016 Florabel C. Navarrete4 Reynaldo B. Inocian5 P-ISSN 2350-7756 Department of Public Governance, College of Arts and Sciences, Cebu Normal E-ISSN 2350-8442 University, Cebu City Philippines, 6000 www.apjmr.com [email protected],[email protected],[email protected], [email protected],[email protected] Date Received: March 10, 2016; Date Revised: May 11, 2016 Abstract-This study featured how a lady local politician rose to power as a barangay captain. It aimed to: describe her leadership orientation before she became a barangay captain, analyze the factors of her success stories in political leadership, extrapolate her values based on the problems/challenges met in the barangay, unveil her initiatives to address these problems, and interpolate her enduring vision for the future of the barangay. Through a biographical research design, with purposive sampling, a key female informant named as Lady L was chosen with the sole criteria of being a female Barangay Captain of Cebu City. Interview guides were utilized in the generation of Lady L’s biographic information about her political career.Lady L’s experiences in waiting for the perfect time and working in the private sector destined her to have a successful political career enhanced with passion and family influence. Encountering problems concerning basic education and unwanted migrants in Barangay K did not discourage her choice to run for re-election, because of her dedication to public service. -

Sports in Pre-Modern and Early Modern Siam: Aggressive and Civilised Masculinities

Sports in Pre-Modern and Early Modern Siam: Aggressive and Civilised Masculinities Charn Panarut A thesis submitted in fulfilment of The requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology and Social Policy Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney 2018 Statement of Authorship This dissertation is the copyrighted work of the author, Charn Panarut, and the University of Sydney. This thesis has not been previously submitted for any degree or other objectives. I certify that this thesis contains no documents previously written or published by anyone except where due reference is referenced in the dissertation itself. i Abstract This thesis is a contribution to two bodies of scholarship: first, the historical understanding of the modernisation process in Siam, and in particular the role of sport in the gradual pacification of violent forms of behaviour; second, one of the central bodies of scholarship used to analyse sport sociologically, the work of Norbert Elias and Eric Dunning on sport and the civilising process. Previous studies of the emergence of a more civilised form of behaviour in modern Siam highlight the imitation of Western civilised conducts in political and sporting contexts, largely overlooking the continued role of violence in this change in Siamese behaviour from the pre- modern to modern periods. This thesis examines the historical evidence which shows that, from around the 1900s, Siamese elites engaged in deliberate projects to civilise prevalent non-elites’ aggressive conducts. This in turn has implications for the Eliasian understanding of sports and civilising process, which emphasises their unplanned development alongside political and economic changes in Europe, at the expense of grasping the deliberate interventions of the Siamese elites. -

From the Library of Garrick Lee Praise for up and out of Poverty

ptg From the Library of Garrick Lee Praise for Up and Out of Poverty “Philip Kotler, pioneer in social marketing, and Nancy Lee bring their inci- sive thinking and pragmatic approach to the problems of behavior change at the bottom of the pyramid. Creative solutions to persistent problems that affect the poor require the tools of social marketing and multi-stakeholder management. In this book, the poor around the world have found new and powerful allies. A must read for those who work to alleviate poverty and restore human dignity.” —CK Prahalad, Paul and Ruth McCracken Distinguished University Pro- fessor, Ross School of Business, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; and author of The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid, 5th Anniversary Edition “Up and Out of Poverty will prove very helpful to antipoverty planners and workers to help the poor deal better with their problems of daily living. Philip Kotler and Nancy Lee illustrate vivid cases of how the poor can be helped by social marketing solutions.” —Mechai Viravaidya, founder and Chairman, ptg Population and Community Development Association, Thailand “Helping others out of poverty is a simple task; yet it remains incomplete. Putting poverty in a museum is achievable within a short span of time—if we all work together, we can do it!” —Muhammad Yunus, winner of the Nobel Prize for Peace; and Managing Director, Grameen Bank “In Up and Out of Poverty, Kotler and Lee remind us that ‘markets’ are peo- ple. A series of remarkable case studies demonstrate conclusively the power of social marketing to release the creative energy of people to solve their own problems. -

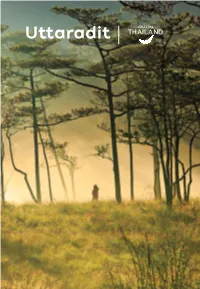

Uttaradit Uttaradit Uttaradit

Uttaradit Uttaradit Uttaradit Namtok Sai Thip CONTENTS HOW TO GET THERE 7 ATTRACTIONS 8 Amphoe Mueang Uttaradit 8 Amphoe Laplae 11 Amphoe Tha Pla 16 Amphoe Thong Saen Khan 18 Amphoe Nam Pat 19 EVENTS & FESTIVALS 23 LOCAL PRODUCTS AND SOUVENIRS 25 INTERESTING ACTIVITIES 27 Agro-tourism 27 Golf Course 27 EXAMPLES OF TOUR PROGRAMMES 27 FACILITIES IN UTTARADIT 28 Accommodations 28 Restaurants 30 USEFUL CALLS 32 Wat Chedi Khiri Wihan Uttaradit Uttaradit has a long history, proven by discovery South : borders with Phitsanulok. of artefacts, dating back to pre-historic times, West : borders with Sukhothai. down to the Ayutthaya and Thonburi periods. Mueang Phichai and Sawangkhaburi were HOW TO GET THERE Ayutthaya’s most strategic outposts. The site By Car: Uttaradit is located 491 kilometres of the original town, then called Bang Pho Tha from Bangkok. Two routes are available: It, which was Mueang Phichai’s dependency, 1. From Bangkok, take Highway No. 1 and No. 32 was located on the right bank of the Nan River. to Nakhon Sawan via Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya, It flourished as a port for goods transportation. Ang Thong, Sing Buri, and Chai Nat. Then, use As a result, King Rama V elevated its status Highway No. 117 and No. 11 to Uttaradit via from Tambon or sub-district into Mueang or Phitsanulok. town but was still under Mueang Phichai. King 2. From Bangkok, drive to Amphoe In Buri via Rama V re-named it Uttaradit, literally the Port the Bangkok–Sing Buri route (Highway No. of the North. Later Uttaradit became more 311). -

Downloadonly

2 Samut Songkhram Samut Songkhram 3 Bangnoi Floating Market 4 Samut Songkhram CONTENTS HOW TO GET THERE 7 ATTRACTIONS 7 Amphoe Mueang 7 Amphoe Amphawa 11 Amphoe Bang Khonthi 23 INTERESTING ACTTIVITIES 25 Boat tour 25 Ecotourism 25 Agro-tourism 26 Homestay 26 EXAMPLES OF PROGRAMMES 28 EVENTS AND FESTIVALS 30 FACILITIES IN SAMUT SONGKHRAM 30 Accommodations 30 Restaurants 35 LOCAL PRODUCTS AND SOUVENIRS 37 USEFUL CALLS 40 Samut Songkhram 5 Rom Hup Market Samut Songkhram 6 Samut Songkhram Samut Songkhram is a small province not HOW TO GET THERE far from Bangkok. It takes a little more than By car Take Highway 35 (Thon Buri–Pak Tho or one hour to the province. For those who enjoy Rama II Road), past the Na Kluea – Maha Chai In- cultural tourism and traditional ways of life, tersection. At around Km. 63, take the elevated this province has much to off er. For example, way into the town of Samut Songkhram. the people here earn a living from vegetable By van There are many routes available and fruit farming, and coconut palm sugar including the Victory Monument-Mae Klong, simmering. Furthermore, the fl oating market Mo Chit–Mae Klong, Bang Na–Maha Chai–Mae at Tha Kha still maintains the traditional way Klong, and Lotus Pin Klao–Mae Klong routes. of life of a community by a canal. By bus The Transport Company Limited of- There is no evidence to indicate the establish- fers a daily bus service between Bangkok and ment of the city of Samut Songkhram. It is Samut Songkhram, leaving the Southern Bus presumed to have been a former district of Terminal on Borommaratchachonnani Road Ratchaburi called ‘Suan Nok’ (outside garden). -

Economic Empowerment for All: an Examination of Women's

Empowerment for all: an examination of women’s experiences and perceptions of economic empowerment in Maha Sarakham, Thailand A thesis submitted to the Graduate School Of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Community Planning In the School of Planning In the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning by Amber David B.A. The College of New Jersey March 2017 Committee Chair: David Edelman, Ph.D. Committee Member: Carolette Norwood, Ph.D. Abstract The year of 2015 was the culmination of the Millennium Development Goals, and the launch of the Sustainable Development Goals. Both the MDGs and SDGs recognize gender equality as a basic human right that, when coupled with women's empowerment, provides a vehicle for poverty eradication and economic development. This renewed global agenda sets the stage for the focus of this research: the investigation of the lived experience of women in northeastern Thailand as a window into their sense of economic empowerment. Via snowball sourcing, fifteen women in Maha Sarakham, Thailand were selected to participate in the study. Through in-depth interviews the researcher discovered that the Isan women of Maha Sarakham have used soft power to empower themselves in the short term and are leveraging higher education to create opportunities for the generations of women empowerment they are raising and influencing. II This Page Intentionally Left Blank. III Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my thesis Chair, Dr. David Edelman of the DAAP School of Planning and my co-Chair, Dr. Carolette Norwood of Women and Gender Studies who have listened and offered guidance as I’ve unraveled, reconstructed, and deciphered all of the stories that I gathered. -

List of Pamb Members Enbanc

LIST OF PAMB MEMBERS ENBANC NAME AND DESIGNATION NAME OF AGENCY LGU's/NGO's/OGA's 1. DR. CORAZON B. GALINATO, CESO, IV Regional Executive Director PAMB Chairman DENR BELEN O. DABA Regional Technical Director for PAWCZMS 2. HON. JUANIDY M. VIÑA Municipal Mayor LGU CONCEPCION 3. HON. DONJIE D. ANIMAS Municipal Mayor LGU SAPANG DALAGA 4. HON. SVETLANA P. JALOSJOS Municipal Mayor LGU BALIANGAO 5. HON. LUISITO B. VILLANUEVA, JR. Municipal Mayor LGU CALAMBA 6. HON AGNES V. VILLANUEVA Municipal Mayor LGU PLARIDEL 7. HON. MARTIN C. MIGRIÑO Municipal Mayor LGU LOPEZ JAENA 8. HON. JASON P. ALMONTE City Mayor CITY OF OROQUIETA 9. HON. JIMMY R. REGALADO Municipal Mayor LGU ALORAN 10. HON. MERIAM L. PAYLAGA Municipal Mayor LGU PANAON 11. HON. RANULFO B. LIMQUIMBO Municipal Mayor LGU JIMENEZ 12. HON. DELLO T. LOOD Municipal Mayor LGU SINACABAN 13. HON. ESTELA R. OBUT-ESTAÑO Municipal Mayor LGU TUDELA 14. HON. DAVID M. NAVARRO Municipal Mayor LGU CLARIN 15. HON. NOVA PRINCESS P. ECHAVEZ City Mayor CITY OF OZAMIZ 16. HON. PHILIP T. TAN City Mayor CITY OF TANGUB 17. HON. SAMSON R. DUMANJUG Municipal Mayor LGU BONIFACIO 18. HON. RODOLFO D. LUNA Municipal Mayor LGU DON VICTORIANO 19. HON. DARIO S. LAPORE Brgy. Gandawan, Barangay Captain Don Victoriano 20. HON. EMELIO C. MEDEL Brgy. Mara-mara, Don Barangay Captain Victoriano 21 HON. JOMAR ENDING Brgy. Lake Duminagat, Don Barangay Captain Victoriano 22. HON. ROMEO M. MALOLOY-ON Brgy. Lalud, Don Victoriano Barangay Captain 23. HON. ROGER D. ACA-AC Brgy. Liboron, Don Victoriano Barangay Captain 24. HON. -

Informal Relationship Patterns Among Staff of Local Health and Non-Health Organizations in Thailand Mano Maneechay1,2 and Krit Pongpirul1,3,4,5*

Maneechay and Pongpirul BMC Health Services Research (2015) 15:113 DOI 10.1186/s12913-015-0781-8 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Informal relationship patterns among staff of local health and non-health organizations in Thailand Mano Maneechay1,2 and Krit Pongpirul1,3,4,5* Abstract Background: Co-operation among staff of local government agencies is essential for good local health services system, especially in small communities. This study aims to explore possible informal relationship patterns among staff of local health and non-health organizations in the context of health decentralization in Thailand. Methods: Tambon Health Promoting Hospital (THPH) and Sub-district Administrative Organization (SAO) represented local health and non-health organizations, respectively. Based on the finding from qualitative interview of stakeholders, a questionnaire was developed to explore individual and organizational characteristics and informal relationships between staff of both organizations. Respondents were asked to draw ‘relationship lines’ between each staff position of health and non-health organizations. ‘Degree of relationship’ was assessed from the number that respondent assigned to each of the lines (1, friend; 2, second-degree relative; 3, first-degree relative; 4, spouse). The questionnaire was distributed to 748 staff of local health and non-health organizations in 378 Tambons. A panel of seven experts was asked to look at all responded questionnaires to familiarize with the content then discussed about possible categorization of the patterns. Results: Responses were received from 73.0% (276/378) Tambons and 59.0% (441/748) staff. The informal relationships were classified into four levels: strong, moderate, weak and no informal relationship, mainly because of potential impact on local health services system.