Analysis of Thai Internet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTERNATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS: DYNAMICS of REGULATION of a RAPIDLY EXPANDING SERVICE Asimr H

INTERNATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS: DYNAMICS OF REGULATION OF A RAPIDLY EXPANDING SERVICE AsImR H. ENDE* I A PROFILE OF THE REGULATORY ISSION The Communications Act of 1934, as amended' (the Communications Act), and the Communicatons Satellite Act of 19622 (the Satellite Act) provide for pervasive and all-encompassing federal regulation of international telecommunications. The basic purposes to be achieved by such regulation are declared to be "to make avail- able, so far as possible, to all the people of the United States a rapid, efficient, Nation-wide, and world-wide wire and radio communications service with adequate facilities at reasonable charges, ...." This broad and general statement of purposes is supplemented by the Declaration of Policy and Purposes in the Satellite Act. In that act, Congress declared it to be the policy of the United States to establish,-in conjunction and cooperation with other countries and as expeditiously as practicable, a commercial communications satellite system which, as part of an improved global communications network, would be responsive to public needs and national objectives, would serve the communications needs of this country and other countries, and would contribute to world peace and understanding In effectuating the above program, care and attention are to be directed toward providing services to economically less developed countries and areas as well as more highly developed ones, toward efficient and economical use of the frequency spectrum, and toward reflecting the benefits of the new technology in both the quality of the services provided and the charges for such services.4 United States participation in the global system is to be in the form of a private corporation subject to appropriate governmental regulation.5 All authorized users are to have nondiscriminatory access to the satellite system. -

The Pluralistic Poverty of Phalang Pracharat

ISSUE: 2021 No. 29 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore | 12 March 2021 Thailand’s Elected Junta: The Pluralistic Poverty of Phalang Pracharat Paul Chambers* Left: Deputy Prime Minister and Phalang Pracharat Party Leader General Prawit Wongsuwan Source:https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Prawit_Wongsuwan_Thailand%27s_Minister_of_D efense.jpg. Right: Prime Minister and Defense Minister General Prayut Chan-ocha Source:https://th.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E0%B9%84%E0%B8%9F%E0%B8%A5%E0%B9%8C:Prayu th_2018_cropped.jpg. * Paul Chambers is Lecturer and Special Advisor for International Affairs, Center of ASEAN Community Studies, Naresuan University, Phitsanulok, Thailand, and, in March-May 2021, Visiting Fellow with the Thailand Studies Programme at the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. 1 ISSUE: 2021 No. 29 ISSN 2335-6677 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • Thailand’s Phalang Pracharat Party is a “junta party” established as a proxy for the 2014-2019 junta and the military, and specifically designed to sustain the power of the generals Prawit Wongsuwan, Prayut Chan-ocha and Anupong Paochinda. • Phalang Pracharat was created by the Internal Security Operations Command (ISOC), and although it is extremely factionalized, having 20 cliques, it is nevertheless dominated by an Army faction headed by General Prawit Wongsuwan. • The party is financed by powerful corporations and by its intra-party faction leaders. • In 2021, Phalang Pracharat has become a model for other militaries in Southeast Asia intent on institutionalising their power. In Thailand itself, the party has become so well- entrenched that it will be a difficult task removing it from office. 2 ISSUE: 2021 No. -

Thailand White Paper

THE BANGKOK MASSACRES: A CALL FOR ACCOUNTABILITY ―A White Paper by Amsterdam & Peroff LLP EXECUTIVE SUMMARY For four years, the people of Thailand have been the victims of a systematic and unrelenting assault on their most fundamental right — the right to self-determination through genuine elections based on the will of the people. The assault against democracy was launched with the planning and execution of a military coup d’état in 2006. In collaboration with members of the Privy Council, Thai military generals overthrew the popularly elected, democratic government of Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, whose Thai Rak Thai party had won three consecutive national elections in 2001, 2005 and 2006. The 2006 military coup marked the beginning of an attempt to restore the hegemony of Thailand’s old moneyed elites, military generals, high-ranking civil servants, and royal advisors (the “Establishment”) through the annihilation of an electoral force that had come to present a major, historical challenge to their power. The regime put in place by the coup hijacked the institutions of government, dissolved Thai Rak Thai and banned its leaders from political participation for five years. When the successor to Thai Rak Thai managed to win the next national election in late 2007, an ad hoc court consisting of judges hand-picked by the coup-makers dissolved that party as well, allowing Abhisit Vejjajiva’s rise to the Prime Minister’s office. Abhisit’s administration, however, has since been forced to impose an array of repressive measures to maintain its illegitimate grip and quash the democratic movement that sprung up as a reaction to the 2006 military coup as well as the 2008 “judicial coups.” Among other things, the government blocked some 50,000 web sites, shut down the opposition’s satellite television station, and incarcerated a record number of people under Thailand’s infamous lèse-majesté legislation and the equally draconian Computer Crimes Act. -

COMMUNICATION and ADVERTISING This Text Is Prepared for The

DESIGN CHRONOLOGY TURKEY COMMUNICATION AND ADVERTISING This text is prepared for the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial ARE WE HUMAN? The Design of the Species 2 seconds, 2 days, 2 years, 200 years, 200,000 years by Gökhan Akçura and Pelin Derviş with contributions by Barış Gün and the support of Studio-X Istanbul translated by Liz Erçevik Amado, Selin Irazca Geray and Gülce Maşrabacı editorial support by Ceren Şenel, Erim Şerifoğlu graphic design by Selin Pervan COMMUNICATION AND ADVERTISING 19th CENTURY perfection of the manuscripts they see in Istanbul. Henry Caillol, who grows an interest in and learns about lithography ALAMET-İ FARİKA (TRADEMARK) in France, figures that putting this technique into practice in Let us look at the market places. The manufacturer wants to Istanbul will be a very lucrative business and talks Jacques distinguish his goods; the tradesman wants to distinguish Caillol out of going to Romania. Henry Caillol hires a teacher his shop. His medium is the sign. He wants to give the and begins to learn Turkish. After a while, also relying on the consumer a message. He is trying to call out “Recognize me”. connections they have made, they apply to the Ministry of He is hanging either a model of his product, a duplicate of War and obtain permission to found a lithographic printing the tool he is working with in front of his store, or its sign, house. They place an order for a printing press from France. one that is diferent, interesting. The tailor hangs a pair of This printing house begins to operate in the annex of the scissors and he becomes known as “the one who is good with Ministry of War (the current Istanbul University Rectorate scissors”. -

Digital Audio Broadcasting : Principles and Applications of Digital Radio

Digital Audio Broadcasting Principles and Applications of Digital Radio Second Edition Edited by WOLFGANG HOEG Berlin, Germany and THOMAS LAUTERBACH University of Applied Sciences, Nuernberg, Germany Digital Audio Broadcasting Digital Audio Broadcasting Principles and Applications of Digital Radio Second Edition Edited by WOLFGANG HOEG Berlin, Germany and THOMAS LAUTERBACH University of Applied Sciences, Nuernberg, Germany Copyright ß 2003 John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England Telephone (þ44) 1243 779777 Email (for orders and customer service enquiries): [email protected] Visit our Home Page on www.wileyeurope.com or www.wiley.com All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England, or emailed to [email protected], or faxed to (þ44) 1243 770571. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the Publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. -

The Two Faces of Thai Authoritarianism

East Asia Forum Economics, Politics and Public Policy in East Asia and the Pacific http://www.eastasiaforum.org The two faces of Thai authoritarianism 29th September, 2014 Author: Thitinan Pongsudhirak Thai politics has completed a dramatic turn from electoral authoritarianism under deposed premier Thaksin Shinawatra in 2001–2006 to a virtual military government under General Prayuth Chan-ocha. These two sides of the authoritarian coin, electoral and military, represent Thailand’s painful learning curve. The most daunting challenge for the country is not to choose one or the other but to create a hybrid that combines electoral sources of legitimacy for democratic rule and some measure of moral authority and integrity often lacked by elected officials. A decade ago, Thaksin was practically unchallenged in Thailand. He had earlier squeaked through an assets concealment trial on a narrow and questionable vote after nearly winning a majority in the January 2001 election. A consummate politician and former police officer, Thaksin benefited from extensive networks in business and the bureaucracy, including the police and army. In politics, his Thai Rak Thai party became a juggernaut. It devised a popular policy platform, featuring affordable universal healthcare, debt relief and microcredit schemes. It won over most of the rural electorate and even the majority of Bangkok. Absorbing smaller parties, Thai Rak Thai virtually monopolised party politics in view of a weak opposition. Thaksin penetrated and controlled supposedly independent agencies aimed at promoting accountability, particularly the Constitutional Court, the Election Commission and the Anti-Corruption Commission. His confidants and loyalists steered these agencies. His cousin became the army’s Commander-in-Chief. -

Internet Service Providers in Thailand

Internet Service Providers In Thailand: Evaluation of Determinants Affecting Customer Loyalty By Student 2 A dissertation submitted for the Masters in Business Administration The Business School University of Roehampton 2011 Declaration Form The work I have submitted is my own effort. I certify that all the material in this Dissertation, which is not my own work, has been identified and acknowledged. No materials are included for which a degree has been previously conferred upon me. Signed Date (Saruta Tangjai) i The Abstract Recently, the Internet service industry in Thailand has been developing and improving their marketing strategies to retain existing customers and create new ones because of a highly competitive market. It is significant for Internet service providers to consider customer satisfaction and customer loyalty in order to help their businesses develop a competitive edge and increase their brand value. In addition, customer loyalty can be a significant factor that helps an Internet service provider increase its profits and create more competitive advantages in the long-term (Oliver, 1999: Lin and Wang, 2006). This research aims to explore the determinants, which affect customer loyalty in the context of Internet service providers in Thailand. A questionnaire survey was conducted with a sample consisting of Thai Internet users in the capital city, Bangkok. The determinants that affect customer loyalty have been tested and analyzed using several approaches so as to explore the significant determinants and understand relationship between the determinants and customer loyalty. The determinants that were analyzed in this research are tangible, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, empathy, pricing, switching cost, trust and brand image. -

History of the Internet-English

Sirin Palasri Steven Huter ZitaWenzel, Ph.D. THE HISTOR Y OF THE INTERNET IN THAILAND Sirin Palasri Steven G. Huter Zita Wenzel (Ph.D.) The Network Startup Resource Center (NSRC) University of Oregon The History of the Internet in Thailand by Sirin Palasri, Steven Huter, and Zita Wenzel Cover Design: Boonsak Tangkamcharoen Published by University of Oregon Libraries, 2013 1299 University of Oregon Eugene, OR 97403-1299 United States of America Telephone: (541) 346-3053 / Fax: (541) 346-3485 Second printing, 2013. ISBN: 978-0-9858204-2-8 (pbk) ISBN: 978-0-9858204-6-6 (English PDF), doi:10.7264/N3B56GNC ISBN: 978-0-9858204-7-3 (Thai PDF), doi:10.7264/N36D5QXN Originally published in 1999. Copyright © 1999 State of Oregon, by and for the State Board of Higher Education, on behalf of the Network Startup Resource Center at the University of Oregon. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/deed.en_US Requests for permission, beyond the Creative Commons authorized uses, should be addressed to: The Network Startup Resource Center (NSRC) 1299 University of Oregon Eugene, Oregon 97403-1299 USA Telephone: +1 541 346-3547 Email: [email protected] Fax: +1 541-346-4397 http://www.nsrc.org/ This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. NCR-961657. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. -

Thailand, July 2005

Description of document: US Department of State Self Study Guide for Thailand, July 2005 Requested date: 11-March-2007 Released date: 25-Mar-2010 Posted date: 19-April-2010 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Office of Information Programs and Services A/GIS/IPS/RL U. S. Department of State Washington, D. C. 20522-8100 Fax: 202-261-8579 Note: This is one of a series of self-study guides for a country or area, prepared for the use of USAID staff assigned to temporary duty in those countries. The guides are designed to allow individuals to familiarize themselves with the country or area in which they will be posted. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. -

From the Library of Garrick Lee Praise for up and out of Poverty

ptg From the Library of Garrick Lee Praise for Up and Out of Poverty “Philip Kotler, pioneer in social marketing, and Nancy Lee bring their inci- sive thinking and pragmatic approach to the problems of behavior change at the bottom of the pyramid. Creative solutions to persistent problems that affect the poor require the tools of social marketing and multi-stakeholder management. In this book, the poor around the world have found new and powerful allies. A must read for those who work to alleviate poverty and restore human dignity.” —CK Prahalad, Paul and Ruth McCracken Distinguished University Pro- fessor, Ross School of Business, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; and author of The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid, 5th Anniversary Edition “Up and Out of Poverty will prove very helpful to antipoverty planners and workers to help the poor deal better with their problems of daily living. Philip Kotler and Nancy Lee illustrate vivid cases of how the poor can be helped by social marketing solutions.” —Mechai Viravaidya, founder and Chairman, ptg Population and Community Development Association, Thailand “Helping others out of poverty is a simple task; yet it remains incomplete. Putting poverty in a museum is achievable within a short span of time—if we all work together, we can do it!” —Muhammad Yunus, winner of the Nobel Prize for Peace; and Managing Director, Grameen Bank “In Up and Out of Poverty, Kotler and Lee remind us that ‘markets’ are peo- ple. A series of remarkable case studies demonstrate conclusively the power of social marketing to release the creative energy of people to solve their own problems. -

Recognizing Legal Differences in Computer Bulletin Board Functions Eric Goldman Santa Clara University School of Law, [email protected]

Santa Clara Law Santa Clara Law Digital Commons Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 1-1-1993 Cyberspace, the Free Market and the Free Marketplace of Ideas: Recognizing Legal Differences in Computer Bulletin Board Functions Eric Goldman Santa Clara University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/facpubs Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation 16 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L.J. 87 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cyberspace, the Free Market and the Free Marketplace of Ideas: Recognizing Legal Differences in Computer Bulletin Board Functions by ERIC SCHLACHTER* Table of Contents I. Difficult Issues Resulting from Changing Technologies.. 89 A. The Emergence of BBSs as a Communication M edium ............................................. 91 B. The Need for a Law of Cyberspace ................. 97 C. The Quest for the Appropriate Legal Analogy Applicable to Sysops ................................ 98 II. Breaking Down Computer Bulletin Board Systems Into Their Key Characteristics ................................ 101 A. Who is the Sysop? ......... 101 B. The Sysop's Control ................................. 106 C. BBS Functions ...................................... 107 1. Message Functions .............................. -

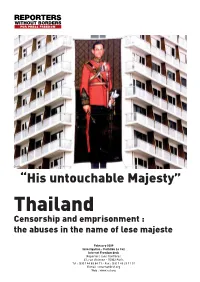

Thailand Censorship and Emprisonment : the Abuses in the Name of Lese Majeste

© AFP “His untouchable Majesty” Thailand Censorship and emprisonment : the abuses in the name of lese majeste February 2009 Investigation : Clothilde Le Coz Internet Freedom desk Reporters sans frontières 47, rue Vivienne - 75002 Paris Tel : (33) 1 44 83 84 71 - Fax : (33) 1 45 23 11 51 E-mail : [email protected] Web : www.rsf.org “But there has never been anyone telling me "approve" because the King speaks well and speaks correctly. Actually I must also be criticised. I am not afraid if the criticism concerns what I do wrong, because then I know. Because if you say the King cannot be criticised, it means that the King is not human.”. Rama IX, king of Thailand, 5 december 2005 Thailand : majeste and emprisonment : the abuses in name of lese Censorship 1 It is undeniable that King Bhumibol According to Reporters Without Adulyadej, who has been on the throne Borders, a reform of the laws on the since 5 May 1950, enjoys huge popularity crime of lese majeste could only come in Thailand. The kingdom is a constitutio- from the palace. That is why our organisa- nal monarchy that assigns him the role of tion is addressing itself directly to the head of state and protector of religion. sovereign to ask him to find a solution to Crowned under the dynastic name of this crisis that is threatening freedom of Rama IX, Bhumibol Adulyadej, born in expression in the kingdom. 1927, studied in Switzerland and has also shown great interest in his country's With a king aged 81, the issues of his suc- agricultural and economic development.