The Attitude Towards the Turks in Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth Under the Reign of Jan Iii Sobieski

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Marywil Came to Be. the Creation of Warsaw's Residential and Commercial Complex in the Light of the Correspondence Betwee

Jarosław Pietrzak HOW MARYWIL CAME TO BE. THE CREATION OF WARSAW’S RESIDENTIAL AND COMMERCIAL COMPLEX IN THE LIGHT OF THE CORRESPONDENCE BETWEEN OTTON FRYDERYK FELKERSAMB AND MARIA KAZIMIERA SOBIESKA FROM 1694* Introduction The area of the Marywil complex, once located between today’s Józefa Piłsudskiego Square and Moliera Street, Wierzbowa Street, and Senatorska Street, currently houses the monumental edifice of Teatr Wielki and its adja- cent parking lot. The history of the complex combining residential and com- mercial functions has already been thoroughly studied and described in sec- ondary sources; it would seem that there is nothing to add or modify within this area of research1. * The text was written as part of the grant project NCN FUGA 4 (agreement UMO-2015/16/S/HS3/00095) entitled “Organisation and operation of the courts of Maria Kazimiera d’Arquien Sobieska in Poland, Italy, and France in the years 1658–1716”. 1 M. Karpowicz, Sztuka oświeconego sarmatyzmu: antykizacja i klasycyzacja w środowisku warszawskim czasów Jana III, Warsaw 1970, pp. 163–165; idem, Sztuka Warszawy drugiej połowy XVII w., Warsaw 1975, pp. 45–47; A. Rychłowska-Kozłowska, Marywil, Warsaw 1975; W. Fijałkowski, Szlakiem Jana III Sobieskiego, Warsaw 1984, pp. 56–61; J. Putkowska, Architektura Warszawy w XVII wieku, Warsaw 1991, pp. 94–97; idem, Warszawskie rezydencje na przedmieściach i pod miastem w XVI–XVIII wieku, Warsaw 2016, pp. 41–42; M. Omilanowska, Świątynie handlu. Warszawska architektura komercyjna doby wielkomiejskiej, Warsaw 2004, pp. 56–59; idem, “Wokół Teatru Wielkiego. Od Marywilu do Pasażu Luxenburga”, Almanach Warszawy 2014, vol. 10, pp. 255–272; T. -

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

TEKA Komisji Architektury, Urbanistyki I Studiów Krajobrazowych XV-2 2019

TEKA 2019, Nr 2 Komisji Architektury, Urbanistyki i Studiów Krajobrazowych Oddział Polskiej Akademii Nauk w Lublinie Revisited the localization of fortifications of the 18th century on the surroundings of village of Braha in Khmelnytsky region Oleksandr harlan https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1473-6417 [email protected] Department of Design and Reconstruction of the Architectural Environment, Prydniprovs’ka State Academy of Civil Engineering and Architecture Abstract: the results of the survey of the territories of the village Braga in the Khmelnytsky region, which is in close prox- imity to Khotyn Fortress, are highlighted in this article. A general description of the sources that has thrown a great deal of light on the fortifications of the left bank of the Dnister River opposite the Khotyn Fortress according to the modern land- scape, is presented. Keywords: monument, fortification, village of Braga, Khotyn fortress, Dnister River Relevance of research Today there is a lack of architectural and urban studies in the context of studying the history of the unique monument – the Khotyn Fortress. Only a few published works can be cited that cover issues of origin, existence of fortifications and it’s preservation. To take into comprehensive account of the specific conservation needs of the Khotyn Fortress, it was necessary to carry out appropriate research works (bibliographic, archival, cartographic, iconographic), including on-site surveys. During 2014−2015, the research works had been carried out by the Research Institute of Conservation Research in the context of the implementation of the Plan for the organization of the territory of the State. During the elaboration of historical sources from the history of the city of Khotyn and the Khotyn Fortress it was put a spotlight on a great number of iconographic materials, concerning the recording of the fortifica- tions of the New Fortress of the 18th-19th centuries. -

![Artyku³y Y- Go 0– 27 Rzed- Lstwo Egen- Płacić Rzynaj- Genealo- Mie Pilnego W Świetle Ch I Domowych Dtym Nigdy Od Żad- I Napisał Na Jego , [W:] M](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1701/artyku%C2%B3y-y-go-0-27-rzed-lstwo-egen-p%C5%82aci%C4%87-rzynaj-genealo-mie-pilnego-w-%C5%9Bwietle-ch-i-domowych-dtym-nigdy-od-%C5%BCad-i-napisa%C5%82-na-jego-w-m-101701.webp)

Artyku³y Y- Go 0– 27 Rzed- Lstwo Egen- Płacić Rzynaj- Genealo- Mie Pilnego W Świetle Ch I Domowych Dtym Nigdy Od Żad- I Napisał Na Jego , [W:] M

artyku³y Stefan Dmitruk (Białystok) Geneza rodu Chodkiewiczów Początki rodu Chodkiewiczów są trudne do ustalenia. Dzieje przodków Grzegorza Chodkiewicza (ok. 1520–1572) sięgają przynaj- mniej początków XV w. Genealogia Chodkiewiczów stanowiła przed- miot licznych dyskusji wśród historyków. Przyjmuje się, że genealo- giczne hipotezy o pochodzeniu Chodkiewiczów dzielą się na legen- darne i naukowe. Prekursorem wywodów mitycznych stał się żyjący w latach 1520– 1584 Augustyn Rotundus. W swym dziele Rozmowy Polaka z Li- twinem pisał, że Chodkiewiczowie to ród litewski wywodzący się od „Chocka”1. Podwaliny pod legendę chodkiewiczowską położył Maciej Stryjkowski (ok. 1547 – ok. 1593). Między 1575 a 1579 r. przeby- wał on na dworze kniazia Jerzego III Słuckiego2 i napisał na jego polecenie pracę O początkach, wywodach, dzielnościach... W świetle jego ustaleń w 1306 r. do księcia Gedymina miało przybyć poselstwo od chana zawołżańskiego3. Poseł tatarski zaproponował pojedynek wojowników – Tatara i Litwina. W przypadku wygranej poddanego litewskiego państwo Gedymina (ok. 1275–1341) przestałoby płacić 1 A. Rotundus, Rozmowy Polaka z Litwinem, Kraków 1890, s. 47. 2 J. Radziszewska, Maciej Stryjkowski i jego dzieło, [w:] M. Stryjkowski, O początkach, wywodach, dzielnościach, sprawach rycerskich i domowych sławnego narodu litewskiego, żemodzkiego i ruskiego, przedtym nigdy od żad- nego ani kuszone, ani opisane, z natchnienia Bożego a uprzejmie pilnego doświadczenia, opr. J. Radziszewska, Warszawa 1978, s. 8, 10. 3 M. Stryjkowski, O początkach..., s. 239–242. 27 haracz. Na dworze książęcym przebywali Żmudzini. Spośród nich do walki o honor Litwy stanął Borejko. Żmudzinowi udało się pokonać Tatara w pojedynku, przez co zwolnił swoją ojczyznę od płacenia da- niny chanowi. Gedymin nagrodził dzielnego wojownika nadając mu Kazyłkiszki, Zblanów, Sochałów oraz odstąpił mu w dzierżawę Stki- wiłowicz i Słonim. -

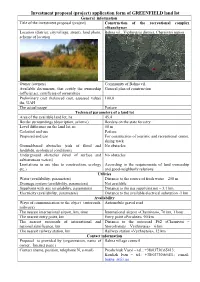

Investment Proposal (Project) Application Form of GREENFIЕLD

Investment proposal (project) application form of GREENFIЕLD land lot General information Title of the investment proposal (project) Construction of the recreational complex «Stanchyna» Location (district, city/village, street), land photo, Bahna vil., Vyzhnytsia district, Chernivtsi region scheme of location Owner (owners) Community of Bahna vil. Available documents, that certify the ownership General plan of construction (official act, certificate of ownership) Preliminary cost (balanced cost, assessed value) 100,0 ths. UAH The actual usage Pasture Technical parameters of a land lot Area of the available land lot, ha 45,4 Border surroundings (description, scheme) Borders on the state forestry Level difference on the land lot, m 50 m Cadastral end use Pasture Proposed end use For construction of touristic and recreational center, skiing track Ground-based obstacles (risk of flood and No obstacles landslide, ecological conditions) Underground obstacles (level of surface and No obstacles subterranean waters) Limitations in use (due to construction, ecology According to the requirements of land ownership etc.) and good-neighborly relations Utilities Water (availability, parameters) Distance to the source of fresh water – 250 m Drainage system (availability, parameters) Not available Supplying with gas (availability, parameters) Distance to the gas supplying net – 3,1 km. Electricity (availability, parameters) Distance to the available electrical substation -1 km Availability Ways of communication to the object (autoroads, Automobile gravel -

The Role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin Struggle for Independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 1-1-1967 The role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin struggle for independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649. Andrew B. Pernal University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Pernal, Andrew B., "The role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin struggle for independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649." (1967). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 6490. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/6490 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. THE ROLE OF BOHDAN KHMELNYTSKYI AND OF THE KOZAKS IN THE RUSIN STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE FROM THE POLISH-LI'THUANIAN COMMONWEALTH: 1648-1649 by A ‘n d r e w B. Pernal, B. A. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History of the University of Windsor in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Graduate Studies 1967 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Did Authorities Crush Russian Orthodox Church Abroad Parish?

FORUM 18 NEWS SERVICE, Oslo, Norway http://www.forum18.org/ The right to believe, to worship and witness The right to change one's belief or religion The right to join together and express one's belief This article was published by F18News on: 4 October 2005 UKRAINE: Did authorities crush Russian Orthodox Church Abroad parish? By Felix Corley, Forum 18 News Service <http://www.forum18.org> Archbishop Agafangel (Pashkovsky) of the Odessa Diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad (ROCA) has told Forum 18 News Service that the authorities in western Ukraine have crushed a budding parish of his church, at the instigation of Metropolitan Onufry, the diocesan bishop of the rival Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate. The head of the village administration, Vasyl Gavrish, denies claims that he threatened parishioners after the ROCA parish submitted a state registration application. When asked by Forum 18 whether an Orthodox church from a non-Moscow Patriarchate jurisdiction could gain registration, Gavrish replied: "We already have a parish of the Moscow Patriarchate here." Both Gavrish and parishioners have stated that the state SBU security service was involved in moves against the parish, but the SBU has denied this along with Bishop Agafangel's claim that there was pressure from the Moscow Patriarchate. Archbishop Agafangel (Pashkovsky) of the Odessa Diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad (ROCA) has accused the authorities of crushing a budding parish of his church, in the small village of Grozintsy in Khotin [Khotyn] district of Chernivtsy [Chernivtsi] region, in western Ukraine bordering Romania. "People were afraid of the authorities' threats and withdrew their signatures on the parish's registration application," he told Forum 18 News Service from Odessa on 27 September. -

Show Publication Content!

PAMIĘTNIKI SEWERYNA BUKARA z rękopismu po raz pierwszy ogłoszone. DREZNO. DRUKIEM I NAKŁADEM J. I. KRASZEWSKIEGO. 1871. 1000174150 0 (JAtCS V łubłjn Tych kilkanaście lat pamiętni ej szych młodośći mojej, Wspomnienia starego człowieka w upominku dla synów przekazuję. Jours heureux, teins lointain, mais jamais oublié. Où tout ce dont le charme intéresse à la vie. Egayait mes destins ignorés de l'envie. (Marie Joseph Chenier.)., Zaczęto d. 28. Czerwca 1845 r. Od lat kilku już ciągłe od was, kochani syno wie, żądania odbierając, abym napisał pamiętniki moje, zawsze wymawiałem się od tego, z pobudek następu jących. Naprzód, iż, podług mnie, ten tylko powinien zajmować się tego rodzaju opisami, kto, czyli sam bez pośrednio, czy też wpływając do czynności znakomi tych w kraju ludzi, dał się zaszczytnie poznać i do konywał rzeczy wartych pamięci. Powtóre : iż doszedł szy już późnego wieku, nie dałem sobie nigdy pracy notowania okoliczności i spraw, których świadkiem by łem, lub do których wpływałem. Trudno więc przy chodzi pozbierać w myśli kilkadziesiąt-letnie fakta. Lecz tłumaczenia moje nie zdołały zaspokoić was, i mocno upieracie się i naglicie na mnie o te niesz częśliwe pamiętniki. — To mi właśnie przypomniało, com wyczytał w opisie jakiegoś podróżującego: że w Chinach ludzie, którzy szukają wsparcia pieniężnego, mają zawsze w kieszeni instrumencik dęty — rodzaj piszczałek, który wrzaskliwy i przerażający głos wy- VIII daje. Postrzegłszy więc w swojéj drodze człowieka, którego powierzchowność obiecuje im zyskowną dona- tywę, zbliżają się do niego, idą za nim krok w krok i dmą w swój instrumencik tak silnie i tak długo, że rad nie rad, dla spokojności swojéj, obdarzyć ich musi. -

Bitwa Pod Chocimiem, Józef Brandt, 1867 R

Śmierć Stanisława Żółkiewskiego w bitwie pod Cecorą, Walery Eljasz-Radzikowski BIT WA POD CHOCIMIEM 2 września – 9 października 1621 r. W relacjach Polski z Turcją cały wiek XVI upłynął pod znakiem pokoju. Plany rozpoczęcia wojny z Turcją snuł co prawda Stefan Batory, jednak król zdawał sobie sprawę z tego, że szansę powodzenia może stworzyć jedynie zbrojny sojusz głównych europejskich potęg. Zaczepną politykę wobec Turcji próbował kontynuować po śmierci Batorego kanclerz i hetman wielki koronny Jan Zamoyski. Zakładając, że ewentualna przyszła wojna powinna się toczyć na ziemiach mołdawskich, hetman starał się ugrunto- wać polskie wpływy w Mołdawii. W ślad Zamoyskiego szły magnackie rody z Ukrainy, mające w Hospodarstwie Mołdawskim rozliczne interesy, wzmocnione nierzadko związkami rodzinnymi z samymi hospodarami. Niezależnie od planów polityków w stosunkach Polski i Turcji występowały stale dwa punkty zapalne: kozackie rajdy łupieskie na wybrzeża Morza Czarnego – „chadzki morskie po dobro tureckie” i tatarskie najazdy na południowo-wschodnie ziemie Rzeczypospolitej. Sytuacja zaostrzała się od początku XVII wieku. Polskie wyprawy na Mołdawię, mające na celu osadzenie na tronie przychylnego hospodara, powtarzały się w 1600 r., 1612 r. i w 1615 r. Turcja uznawała te wyprawy za mieszanie się w jej wewnętrzne sprawy, jako że już od początku XVI wieku Mołdawia była uznawana za część Imperium Osmańskiego. Równie wielkie oburzenie wywoływało tolerowanie przez Rzeczpospolitą kozackich rajdów. Kozacy zaporoscy na lekkich łodziach „czajkach” zabierających ok. 60 ludzi spływali w dół Dniepru, omijali turec- ką twierdzę w Oczakowie i wypływali na Morze Czarne, gdzie rabowali statki handlowe, nadmorskie wsie, miasteczka i porty. Niejednokrotnie atakowali z powodzeniem wojenne galery tureckie. W 1606 r. napadli Warnę, w 1614 r. -

Materiały Muzeum Wnętrz Zabytkowych W Pszczynie Vii

MATERIAŁY MUZEUM WNĘTRZ ZABYTKOWYCH W PSZCZYNIE VII Tom dedykowany _ _ _ • Prof. Zdzisławowi Zygulskiemu jun. MATERIAŁY MUZEUM WNĘTRZ ZABYTKOWYCH W PSZCZYNIE VII PSZCZYNA 1992 Redakcja: Janusz Ziembiński Projekt okładki: Jan Kruczek Fotografie do rycin wykonali Autorzy lub pochodzą, z archiwów muzealnych pracowni foto graficznych Na okładce: Jan Piotr Norblin (1745— 1830), Widok świątyni Sybilli w Puławach. Fragment, zbiory Muzeum Książąt Czartoryskich w Krakowie, nr inw. MNK 11-3311 ISSN 0209-3162 Wydawnictwo Muzeum Wnętrz Zabytkowych w Pszczynie Ark. wyd. 22,0, ark. druk. 21,25 Druk wykonał Ośrodek Wydawniczy „Augustana” w Bielsku-Białej KSIĘGA PAMIĄTKOWA PROF. DR HAB. ZDZISŁAWA ŻYGULSKIEGO JUN. Janusz Ziembiński, W stęp .................................................................................................................. 9 Zdzisław Żygulski jun., Spotkania na ścieżkach nauki (noty autobiograficzne) .... 11 Jerzy Banach, Order Złotego Runa na widoku Krakowa z pierwszych lat siedemnastego w ie k u ...................................................................................................................................................... 42 Lionello Giorgio Boccia, Tra Firenze, Bisanzio, e di altre c o s e .......................................... 53 Juliusz A. Chrościcki, Islam w nowożytnych ulotkach (informacja i środki propagandy) 64 Tadeusz Chrzanowski, Refleksje nad zbiorami parafialnymi.................................................... 88 Aleksander Czerwiński, W zbrojowni Zakonu Maltańskiego. Polscy muzeolodzy -

The Stolen Museum: Have United States Art Museums Become Inadvertent Fences for Stolen Art Works Looted by the Nazis in World War Ii?

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Faculty Articles and Essays Faculty Scholarship 1999 The tS olen Museum: Have United States Art Museums Become Inadvertent Fences for Stolen Art Works Looted by the Nazis in Word War II? Barbara Tyler Cleveland State University, [email protected] How does access to this work benefit oy u? Let us know! Publisher's Statement Copyright permission granted by the Rutgers University Law Journal. Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/fac_articles Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Original Citation Barbara Tyler, The tS olen Museum: Have United States Art Museums Become Inadvertent Fences for Stolen Art Works Looted by the Nazis in Word War II? 30 Rutgers Law Journal 441 (1999) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Articles and Essays by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: 30 Rutgers L.J. 441 1998-1999 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Mon May 21 10:04:33 2012 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=0277-318X THE STOLEN MUSEUM: HAVE UNITED STATES ART MUSEUMS BECOME INADVERTENT FENCES FOR STOLEN ART WORKS LOOTED BY THE NAZIS IN WORLD WAR II? BarbaraJ. -

Framing 'Turks': Representations of Ottomans and Moors in Continental European Literature 1453-1683

16 2019 FRAMING ‘TURKS’: Representations of Ottomans and Moors in Continental European Literature 1453-1683 ed. Peter Madsen Framing ‘Turks’: Representations of Ottomans and Moors in Continental European Litera- ture 1453-1683, ed. Peter Madsen Nordic Journal of Renaissance Studies 16 • 2019 General Editor of NJRS: Camilla Horster (NJRS was formerly known as Renæssanceforum: Journal of Renaissance Studies) ISSN 2597-0143. URL: www.njrs.dk/njrs_16_2019.htm FRAMING ‘TURKS’ NJRS 16 • 2019 • www.njrs.dk Preface The focus of this issue of Nordic Journal of Renaissance Studies is on Conti- nental Europe, i.e., areas bordering or situated near the Ottoman Empire or otherwise involved in close encounters. It has thus been important to include often neglected, yet most important nations like The Polish-Lithuanian Com- monwealth and Hungary (following the lead of the excellent volume edited by Bodo Guthmüller and Wilhelm Kühlmann: Europa und die Türken in der Renaissance, Tübingen 2000). It has also been important to consider literature beyond well-known classics, thus including works that attracted more atten- tion in their own times than they do today. Finally, it should be underscored how the literary (and intellectual) field beyond the vernaculars included pub- lications in Latin. The introduction is an attempt to situate the subject matter of the individual contributions within a broader historical, intellectual and literary field, thus including further documentation and additional literary examples. ‘Turks’ was the current denomination of contemporary Muslims, whether North African or Spanish ‘Moors’, or inhabitants of the Ottoman Empire or its spheres of various sorts of influence. It should be stressed, though, that although the Ottomans in terms of power and political establishment were Turkish, the inhabitants of the Empire were multi-ethnic and multi-religious.