The Gift Henry Kingsbury Kennebunk, Maine Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rethinking Fideism Through the Lens of Wittgenstein's Engineering Outlook

University of Dayton eCommons Religious Studies Faculty Publications Department of Religious Studies 2012 Rethinking Fideism through the Lens of Wittgenstein’s Engineering Outlook Brad Kallenberg University of Dayton, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/rel_fac_pub Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, Other Religion Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons eCommons Citation Kallenberg, Brad, "Rethinking Fideism through the Lens of Wittgenstein’s Engineering Outlook" (2012). Religious Studies Faculty Publications. 82. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/rel_fac_pub/82 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Religious Studies at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Note: This is the accepted manuscript for the following article: Kallenberg, Brad J. “Rethinking Fideism through the Lens of Wittgenstein’s Engineering Outlook.” International Journal for Philosophy of Religion 71, no. 1 (2012): 55-73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11153-011-9327-0 Rethinking Fideism through the Lens of Wittgenstein’s Engineering Outlook Brad J. Kallenberg University of Dayton, 2011 In an otherwise superbly edited compilation of student notes from Wittgenstein’s 1939 Lectures on the Foundations of Mathematics, Cora Diamond makes an false step that reveals to us our own tendencies to misread Wittgenstein. The student notes she collated attributed the following remark to a student named Watson: “The point is that these [data] tables do not by themselves determine that one builds the bridge in this way: only the tables together with certain scientific theory determine that.”1 But Diamond thinks this a mistake, presuming instead to change the manuscript and put these words into the mouth of Wittgenstein. -

Family-Memoirs – About Strategies of Creating Identity in Vienna of the 1940S

Family-Memoirs – About strategies of creating identity in Vienna of the 1940s. By example of the family of Ludwig Wittgenstein. Nicole L. Immler, University of Graz My talk will be about one of the most quoted sources concerning the biography of the well known austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, who studied philosophy in Cambridge and later became professor of philosophy at Trinity- College: The family memoirs written by Hermine Wittgenstein, the sister of the philosopher, in the years 1944–49 in Vienna.1 The Typescript is so far unpublished, with the exception of the section concerning Ludwig Wittgenstein 2, and was never contextualised as a whole. To use the Familienerinnerungen as a historical source it‘s f i r s t l y necessary to picture the relevance of family memoirs from the perspective of recent theories about memory culture. S e c o n d l y it is to ask about the general historical background of the literary genre family memoirs as such, about the intentions and functions of this genre as well as its origin. Specifically related to the Wittgenstein memoirs I want to follow the thesis, if they can be read as an example of a strategy to create identity for a bourgeois family in Vienna in the nineteenforties. Finally and f o u r t h y, I want to ‚proof- read‘ one argument made by Hermine Wittgenstein by comparing it to arguments of Ludwig Wittgenstein in his writings. Owing to their differences in living conditions, character and experiences, they have different approaches towards a geographical and emotional concept of home. -

Russian Piano Music Series, Vol. 13: Sergei Rachmaninov

Russian Piano Music Series, vol. 13: Sergei Rachmaninov Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943) 1 Etude-Tableau in A minor, Op. 39 No. 2 8:15 Moments Musicaux, Op. 16 31:21 2 No. 1 Andantino in B flat minor 8:50 3 No. 2 Allegretto in E flat minor 3:49 4 No. 3 Andante cantabile in B minor 4:42 5 No. 4 Presto in E minor 3:32 6 No. 5 Adagio sostenuto in D flat major 4:29 7 No. 6 Maestoso in C major 5:52 Piano Sonata No. 1 in D minor, Op. 28 40:20 8 I Allegro moderato 15:38 9 II Lento 9:34 10 III Allegro molto 15:06 total duration : 79:56 Alfonso Soldano piano Dedication I wish to dedicate this album to the great Italian pianist and professor Paola Bruni. Paola was a special friend, and there was no justice in her sad destiny; she was a superlative human being, deep, special and joyful always, as was her playing… everybody will miss you forever Paola! Alfonso Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943) “The Wanderer’s Illusions” by Rosellina de Bellis ".. What I try to do, when I write my music, is to say simply and directly what is in my heart when I compose. If there is love, or bitterness, or sadness, or religion, these moods become part of my music .. " The bitterness of the words spoken by Schubert about the connection between song and love, "... when I wanted to sing love it turned into pain, and if I wanted to sing pain, it became love; so both divide my soul.. -

La Orquesta En La Cámara

LA ORQUESTA EN LA CÁMARA CICLO DE MIÉRCOLES DEL 16 DE OCTUBRE AL 6 DE NOVIEMBRE DE 2019 ZIP 1 LA ORQUESTA EN LA CÁMARA CICLO DE MIÉRCOLES DEL 16 DE OCTUBRE AL 6 DE NOVIEMBRE DE 2019 FUNDACIÓN JUAN MARCH cceder al repertorio sinfónico, aunque no se den las condiciones materiales para su interpretación. Esta es la premisa que proclama el arreglo cuando adapta las composiciones orquestales para formaciones de menor tamaño. Pero esta opción plantea un reto fundamental: ¿cómo convertirA una obra sinfónica en una pieza camerística sin que pierda su esencia? Mahler, Webern o Eisler son solo algunos de los grandes compositores que respondieron a este reto y supieron transformar grandes composiciones orquestales −como las de Bruckner− sin renunciar a su naturaleza monumental. En muchos casos, sus arreglos fueron concebidos para la Verein für musikalische Privataufführungen, una asociación promovida por Schönberg en Viena con el objetivo de difundir la música del momento. Fundación Juan March Por respeto a los demás asistentes, les rogamos que desconecten sus teléfonos móviles y no abandonen la sala durante el acto. ÍNDICE 7 DE LA MÚSICA DE CÁMARA A LA ORQUESTA… Y VICEVERSA: UNA INTERACCIÓN FECUNDA Gabriel Menéndez Torrellas 18 Miércoles, 16 de octubre Robert Murray, tenor Jonathan McGovern, barítono Natalia Ensemble 30 Miércoles, 23 de octubre ZIP Marialena Fernandes y Ranko Marković, piano a cuatro manos 38 Miércoles, 30 de octubre Elena Aguado, Ana Guijarro, Mariana Gurkova y Sebastián Mariné, dos pianos a ocho manos 48 Miércoles, 6 de noviembre Linos Ensemble 58 Lista de los programas de concierto de la Verein für musikalische Privataufführungen (Viena, 1918-1921) 76 Bibliografía Autor de las notas al programa De la música de cámara a la orquesta… y viceversa: una interacción fecunda Gabriel Menéndez Torrellas CONCEPTOS YUXTAPUESTOS: Sebastian Bach puede ilustrar el ini- LO CAMERÍSTICO Y LO ORQUESTAL cio de esta exposición. -

With a Rich History Steeped in Tradition, the Courage to Stand Apart and An

With a rich history steeped in tradition, the courage to stand apart and an enduring joy of discovery, the Wiener Symphoniker are the beating heart of the metropolis of classical music, Vienna. For 120 years, the orchestra has shaped the special sound of its native city, forging a link between past, present and future like no other. In Andrés Orozco-Estrada - for several years now an adopted Viennese - the orchestra has found a Chief Conductor to lead this skilful ensemble forward from the 20-21 season onward, and at the same time revisit its musical roots. That the Wiener Symphoniker were formed in 1900 of all years is no coincidence. The fresh wind of Viennese Modernism swirled around this new orchestra, which confronted the challenges of the 20th century with confidence and vision. This initially included the assured command of the city's musical past: they were the first orchestra to present all of Beethoven's symphonies in the Austrian capital as one cycle. The humanist and forward-looking legacy of Beethoven and Viennese Romanticism seems tailor-made for the Symphoniker, who are justly leaders in this repertoire to this day. That pioneering spirit, however, is also evident in the fact that within a very short time the Wiener Symphoniker rose to become one of the most important European orchestras for the premiering of new works. They have given the world premieres of many milestones of music history, such as Anton Bruckner's Ninth Symphony, Arnold Schönberg's Gurre-Lieder, Maurice Ravel's Piano Concerto for the Left Hand and Franz Schmidt's The Book of the Seven Seals - concerts that opened a door onto completely new worlds of sound and made these accessible to the greater masses. -

Dec 21 to 27.Txt

CLASSIC CHOICES PLAYLIST Dec. 21 - 27, 2020 PLAY DATE: Mon, 12/21/2020 6:02 AM Antonio Vivaldi Concerto, Op. 3, No. 10 6:12 AM TRADITIONAL Gabriel's Message (Basque carol) 6:17 AM Francisco Javier Moreno Symphony 6:29 AM Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber Sonata No.4 6:42 AM Johann Christian Bach Sinfonia Concertante for Violin, Cello 7:02 AM Various In dulci jubilo/Wexford Carol/N'ia gaire 7:12 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Sonata No. 7 7:30 AM Georg Philipp Telemann Concerto for Trumpet and Violin 7:43 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Concerto 8:02 AM Henri Dumont Magnificat 8:15 AM Johann ChristophFriedrich Bach Oboe Sonata 8:33 AM Franz Krommer Concerto for 2 Clarinets 9:05 AM Joaquin Turina Sinfonia Sevillana 9:27 AM Philippe Gaubert Three Watercolors for Flute, Cello and 9:44 AM Ralph Vaughan Williams Fantasia on Christmas Carols 10:00 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Prelude & Fugue after Bach in d, 10:07 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Sonata No. 9 10:25 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 29 10:50 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Prelude (Fantasy) and Fugue 11:01 AM Mily Balakirev Symphony No. 2 11:39 AM Georg Philipp Telemann Overture (suite) for 3 oboes, bsn, 2vns, 12:00 PM THE CHRISTMAS REVELS: IN CELEBRATION OF THE WINTER SOLSTICE 1:00 PM Richard Strauss Oboe Concerto 1:26 PM Ludwig Van Beethoven String Quartet No. 9 2:00 PM James Pierpont Jingle Bells 2:07 PM Julius Chajes Piano Trio 2:28 PM Francois Devienne Symphonie Concertante for flute, 2:50 PM Antonio Vivaldi Concerto, "Il Riposo--Per Il Natale" 3:03 PM Zdenek Fibich Symphony No. -

A History of Rhythm, Metronomes, and the Mechanization of Musicality

THE METRONOMIC PERFORMANCE PRACTICE: A HISTORY OF RHYTHM, METRONOMES, AND THE MECHANIZATION OF MUSICALITY by ALEXANDER EVAN BONUS A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2010 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of _____________________________________________________Alexander Evan Bonus candidate for the ______________________Doctor of Philosophy degree *. Dr. Mary Davis (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) Dr. Daniel Goldmark ________________________________________________ Dr. Peter Bennett ________________________________________________ Dr. Martha Woodmansee ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) _______________________2/25/2010 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Copyright © 2010 by Alexander Evan Bonus All rights reserved CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES . ii LIST OF TABLES . v Preface . vi ABSTRACT . xviii Chapter I. THE HUMANITY OF MUSICAL TIME, THE INSUFFICIENCIES OF RHYTHMICAL NOTATION, AND THE FAILURE OF CLOCKWORK METRONOMES, CIRCA 1600-1900 . 1 II. MAELZEL’S MACHINES: A RECEPTION HISTORY OF MAELZEL, HIS MECHANICAL CULTURE, AND THE METRONOME . .112 III. THE SCIENTIFIC METRONOME . 180 IV. METRONOMIC RHYTHM, THE CHRONOGRAPHIC -

Symposium Records Cd 1109 Adolf Busch

SYMPOSIUM RECORDS CD 1109 The Great Violinists – Volume 4 ADOLF BUSCH (1891-1952) This compact disc documents the early instrumental records of the greatest German-born musician of this century. Adolf Busch was a legendary violinist as well as a composer, organiser of chamber orchestras, founder of festivals, talented amateur painter and moving spirit of three ensembles: the Busch Quartet, the Busch Trio and the Busch/Serkin Duo. He was also a great man, who almost alone among German gentile musicians stood out against Hitler. His concerts between the wars inspired a generation of music-lovers and musicians; and his influence continued after his death through the Marlboro Festival in Vermont, which he founded in 1950. His associate and son-in-law, Rudolf Serkin (1903-1991) maintained it until his own death, and it is still going strong. Busch's importance as a fiddler was all the greater, because he was the last glory of the short-lived German school; Georg Kulenkampff predeceased him and Hitler's decade smashed the edifice built up by men like Joseph Joachim and Carl Flesch. Adolf Busch's career was interrupted by two wars; and his decision to boycott his native country in 1933, when he could have stayed and prospered as others did, further fractured the continuity of his life. That one action made him an exile, cost him the precious cultural nourishment of his native land and deprived him of his most devoted audience. Five years later, he renounced all his concerts in Italy in protest at Mussolini's anti-semitic laws. -

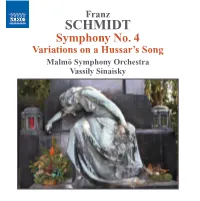

Franz Schmidt

Franz Schmidt (1874 – 1939) was born in Pressburg, now Bratislava, a citizen of the Austro- Hungarian Empire and died in Vienna, a citizen of the Nazi Reich by virtue of Hitler's Anschluss which had then recently annexed Austria into the gathering darkness closing over Europe. Schmidt's father was of mixed Austrian-Hungarian background; his mother entirely Hungarian; his upbringing and schooling thoroughly in the prevailing German-Austrian culture of the day. In 1888 the Schmidt family moved to Vienna, where Franz enrolled in the Conservatory to study composition with Robert Fuchs, cello with Ferdinand Hellmesberger and music theory with Anton Bruckner. He graduated "with excellence" in 1896, the year of Bruckner's death. His career blossomed as a teacher of cello, piano and composition at the Conservatory, later renamed the Imperial Academy. As a composer, Schmidt may be seen as one of the last of the major musical figures in the long line of Austro-German composers, from Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms, Bruckner and Mahler. His four symphonies and his final, great masterwork, the oratorio Das Buch mit sieben Siegeln (The Book with Seven Seals) are rightly seen as the summation of his creative work and a "crown jewel" of the Viennese symphonic tradition. Das Buch occupied Schmidt during the last years of his life, from 1935 to 1937, a time during which he also suffered from cancer – the disease that would eventually take his life. In it he sets selected passages from the last book of the New Testament, the Book of Revelation, tied together with an original narrative text. -

Bruno Walter (Ca

[To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] Erik Ryding and Rebecca Pechefsky Yale University Press New Haven and London Frontispiece: Bruno Walter (ca. ). Courtesy of Österreichisches Theatermuseum. Copyright © by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections and of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Designed by Sonia L. Shannon Set in Bulmer type by The Composing Room of Michigan, Grand Rapids, Mich. Printed in the United States of America by R. R. Donnelley,Harrisonburg, Va. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ryding, Erik S., – Bruno Walter : a world elsewhere / by Erik Ryding and Rebecca Pechefsky. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references, filmography,and indexes. ISBN --- (cloth : alk. paper) . Walter, Bruno, ‒. Conductors (Music)— Biography. I. Pechefsky,Rebecca. II. Title. ML.W R .Ј—dc [B] - A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. For Emily, Mary, and William In memoriam Rachel Kemper and Howard Pechefsky Contents Illustrations follow pages and Preface xi Acknowledgments xv Bruno Schlesinger Berlin, Cologne, Hamburg,– Kapellmeister Walter Breslau, Pressburg, Riga, Berlin,‒ -

570034Bk Hasse 23/8/10 5:34 PM Page 4

572118bk Schmidt4:570034bk Hasse 23/8/10 5:34 PM Page 4 Vassily Sinaisky Vassily Sinaisky’s international career was launched in 1973 when he won the Gold Franz Medal at the prestigious Karajan Competition in Berlin. His early work as Assistant to the legendary Kondrashin at the Moscow Philharmonic, and his study with Ilya Musin at the Leningrad Conservatory provided him with an incomparable grounding. SCHMIDT He has been professor in conducting at the Music Conservatory in St Petersburg for the past thirty years. Sinaisky was Music Director and Principal Conductor of the Photo: Jesper Lindgren Moscow Philharmonic from 1991 to 1996. He has also held the posts of Chief Symphony No. 4 Conductor of the Latvian Symphony and Principal Guest Conductor of the Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra. He was appointed Music Director and Principal Variations on a Hussar’s Song Conductor of the Russian State Orchestra (formerly Svetlanov’s USSR State Symphony Orchestra), a position which he held until 2002. He is Chief Guest Conductor of the BBC Philharmonic and is a regular and popular visitor to the BBC Malmö Symphony Orchestra Proms each summer. In January 2007 Sinaisky took over as Principal Conductor of the Malmö Symphony Orchestra in Sweden. His appointment forms part of an ambitious new development plan for Vassily Sinaisky the orchestra which has already resulted in hugely successful projects both in Sweden and further afield. In September 2009 he was appointed a ‘permanent conductor’ at the Bolshoi in Moscow (a position shared with four other conductors). Malmö Symphony Orchestra The Malmö Symphony Orchestra (MSO) consists of a hundred highly talented musicians who demonstrate their skills in a wide range of concerts. -

Evolution of One-Handed Piano Compositions

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE Evolution of One-Handed Piano Compositions Ignat Drozdov, BS, Mark Kidd, PhD, Irvin M. Modlin, MD, PhD Electronic searches were performed to investigate the evolution of one-handed piano com- positions and one-handed music techniques, and to identify individuals responsible for the development of music meant for playing with one hand. Particularly, composers such as Liszt, Ravel, Scriabin, and Prokofiev established a new model in music by writing works to meet the demands of a variety of pianist-amputees that included Count Géza Zichy (1849– 1924), Paul Wittgenstein (1887–1961), and Siegfried Rapp (b. 1915). Zichy was the first to amplify the scope of the repertoire to improve the variety of one-handed music; Wittgenstein developed and adapted specific and novel performance techniques to accommodate one- handedness; and Rapp sought to promote the stature of one-handed pianists among a musically sophisticated public able to appreciate the nuances of such maestros. (J Hand Surg 2008;33A:780–786. Copyright © 2008 by the American Society for Surgery of the Hand. All rights reserved.) Key words Amputation, hand, history of surgery, music, piano. UCH HAS BEEN WRITTEN ABOUT the creativity of EVOLUTION OF THE PIANO: OF FINGERS AND composers and the skills of musicians, and KEYS Mspecial emphases have been placed on the Pianists are graced with a rich and remarkable history of mind and the vagaries of neurosis and even madness in their instrument, which encompasses more than 850 the process of composition. Little consideration has years of development and evolution.1 From the keyed been given to physical defects and their influence on monochord in 1157, to the clavichord (late Medieval), both music and its interpretation.