"You Must Defeat Shen Long to Stand a Chance": Street Fighter, Race, Play, and Player

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arcana Heart 2 Ost Download

Arcana Heart 2 Ost Download Arcana Heart 2 Ost Download 1 / 3 2 / 3 Shop Arcana Heart 2: Heartful Sound / Game O.S.T.. Everyday low prices and free delivery on eligible orders.. ARCANA HEART GAMEPLAY FOR PS2 Arcana Heart, Fighting Games, Ps2, ... Infinite Stratos 2 Ignition Hearts ps3 iso rom download Gaming Wallpapers ... Shogun: Total War soundtrack by Jeff van Dyck News Games, Video Games, Thing .... Sweet Fighter! Experience the insanity of girl-on-girl action, in a fighting game like no other! Beautiful sprites and vibrant anime artwork combine to create a .... Shop Arcana Heart 2: Heartful Sound / Game O.S.T. by Arcana Heart 2 Heartful Soundcollect [Music CD]. Everyday low prices and free delivery on eligible .... Arcana Heart 2: Heartful Sound / Game O.S.T. by Arcana Heart 2 Heartful Soundcollect (2008-04-15) - Amazon.com Music.. Performer: Original Soundtrack; Album: Arcana Heart: Episode 2; Size .rar MP3: 1598 mb | Size .rar FLAC/APE: 1470 mb; Genre: Stage & Screen; Style: .... 01 - Motoharu Yoshihira - Arcana Heart 2 (Opening), 1:07, Download. 02 - Motoharu Yoshihira - Maidens ver.2 (Character Select), 0:59 .... 2D fighting game The unique 2D fighting game action of the Arcana Heart series continues with this latest edition English ... 2 987 contributeurs ont engagé 324 639 $ pour soutenir ce projet. ... The digital rewards below are ready for download today! ... *This reward was previously referred to as “Digital OST for SixStarS!!!!!!”.. Arcana Heart (アルカナハート, Arukana Hāto) is a 2D arcade fighting game series developed by ... On October 30, 2008, Examu released a major update to Arcana Heart 2 called Suggoi! .. -

October 24, 2019

APT41 10/24/2019 Report #: 201910241000 Agenda • APT41 • Overview • Industry targeting timeline and geographic targeting • A very brief (recent) history of China • China’s economic goals matter to APT41 because… • Why does APT41 matter to healthcare? • Attribution and linkages Image courtesy of PCMag.com • Weapons • Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) • References • Questions Slides Key: Non-Technical: managerial, strategic and high-level (general audience) Technical: Tactical / IOCs; requiring in-depth knowledge (sysadmins, IRT) TLP: WHITE, ID# 201910241000 2 Overview • APT41 • Active since at least 2012 • Assessed by FireEye to be: • Chinese state-sponsored espionage group • Cybercrime actors conducts financial theft for personal gain • Targeted industries: • Healthcare • High-tech • Telecommunications • Higher education • Goals: • Theft of intellectual property • Surveillance • Theft of money • Described by FireEye as… • “highly-sophisticated” • “innovative” and “creative” TLP: WHITE, ID# 201910241000 3 Industry targeting timeline and geographic targeting Image courtesy of FireEye.com • Targeted industries: • Gaming • Healthcare • Pharmaceuticals • High tech • Software • Education • Telecommunications • Travel • Media • Automotive • Geographic targeting: • France, India, Italy, Japan, Myanmar, the Netherlands, Singapore, South Korea, South Africa, Switzerland, Thailand, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States and Hong Kong TLP: WHITE, ID# 201910241000 4 A very brief (recent) history of China • First half of 20th century, Chinese -

Street Fighter

STREET FIGHTER by Luis Filipe Based on Capcom's videogame "Street Fighter II" Copyright © 2019 This is a fan script [email protected] OVER BLACK. All we hear is the excited CHEER of a crowd. Hundreds of voices roaring in unison, teasing something to come. Under those voices, there is also the rhythmic sound of TRAMPLES on the floor that sound like drums. CUT TO: INT. CORRIDOR - NIGHT A dirty, dimly lit corridor. A few meters ahead, a beam of light leaks through a door that gives access to another scenario. Standing in the corridor hidden in total shadow, a barefoot MAN attired in a white karate gi uniform tightens a black martial arts BELT. We do not see his face. The cheer continues, seeming to be coming from beyond that door in the hallway. After putting on the belt, the man takes a pair of RED GLOVES from his duffel bag, which is on a bench beside him. He wears them calmly. Finally, he also grabs a RED HEADBAND from the bag and ties it around his head. All this is almost ritualistic for him. When completed, the mysterious man walks toward the corridor door where comes the intense light. INT. STREET FIGHTER ARENA - NIGHT A large warehouse-like room. Wooden boxes surround the boundaries of the fighting area. And behind these boxes are the spectators, some sit in stands and others stand on feet. Our mysterious man comes in, revealing his face for the first time: RYU. A Japanese experienced martial artist. The audience goes wild to see him there. -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of Items 0

Done In this Category Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of items 0 "X" Title Date Added 0 Day Attack on Earth July--2012 0-D Beat Drop July--2012 1942 Joint Strike July--2012 3 on 3 NHL Arcade July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf Adventures 2 July--2012 50 Cent: Blood on the Sand July--2012 A World of Keflings July--2012 Ace Combat 6: Fires of Liberation July--2012 Ace Combat: Assault Horizon July--2012 Aces of Galaxy Aug--2012 Adidas miCoach (2 Discs) Aug--2012 Adrenaline Misfits Aug--2012 Aegis Wings Aug--2012 Afro Samurai July--2012 After Burner: Climax Aug--2012 Age of Booty Aug--2012 Air Conflicts: Pacific Carriers Oct--2012 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars Dec--2012 Akai Katana July--2012 Alan Wake July--2012 Alan Wake's American Nightmare Aug--2012 Alice Madness Returns July--2012 Alien Breed 1: Evolution Aug--2012 Alien Breed 2: Assault Aug--2012 Alien Breed 3: Descent Aug--2012 Alien Hominid Sept--2012 Alien vs. Predator Aug--2012 Aliens: Colonial Marines Feb--2013 All Zombies Must Die Sept--2012 Alone in the Dark Aug--2012 Alpha Protocol July--2012 Altered Beast Sept--2012 Alvin and the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked July--2012 America's Army: True Soldiers Aug--2012 Amped 3 Oct--2012 Amy Sept--2012 Anarchy Reigns July--2012 Ancients of Ooga Sept--2012 Angry Birds Trilogy Sept--2012 Anomaly Warzone Earth Oct--2012 Apache: Air Assault July--2012 Apples to Apples Oct--2012 Aqua Oct--2012 Arcana Heart 3 July--2012 Arcania Gothica July--2012 Are You Smarter that a 5th Grader July--2012 Arkadian Warriors Oct--2012 Arkanoid Live -

Acquiring Literacy: Techne, Video Games and Composition Pedagogy

ACQUIRING LITERACY: TECHNE, VIDEO GAMES AND COMPOSITION PEDAGOGY James Robert Schirmer A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2008 Committee: Kristine L. Blair, Advisor Lynda D. Dixon Graduate Faculty Representative Richard C. Gebhardt Gary Heba © 2008 James R. Schirmer All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Kristine L. Blair, Advisor Recent work within composition studies calls for an expansion of the idea of composition itself, an increasing advocacy of approaches that allow and encourage students to greater exploration and more “play.” Such advocacy comes coupled with an acknowledgement of technology as an increasingly influential factor in the lives of students. But without a more thorough understanding of technology and how it is manifest in society, any technological incorporation is almost certain to fail. As technology advances along with society, it is of great importance that we not only keep up but, in fact, reflect on process and progress, much as we encourage students to do in composition courses. This document represents an exercise in such reflection, recognizing past and present understandings of the relationship between technology and society. I thus survey past perspectives on the relationship between techne, phronesis, praxis and ethos with an eye toward how such associative states might evolve. Placing these ideas within the context of video games, I seek applicable explanation of how techne functions in a current, popular technology. In essence, it is an analysis of video games as a techno-pedagogical manifestation of techne. With techne as historical foundation and video games as current literacy practice, both serve to improve approaches to teaching composition. -

Adjustment Description Alterations to V-Shift's

Adjustment Description Abilities granting invincibility or armor from the 1st frame, as well as low- risk or high-return moves invincible to throws have all been adjusted to have less effective throw invincibility. Alterations to V-Shift's Considering V-Shift's offensive and defensive capabilities, normal throws offensive/defensive should have enough impact to reliably handle V-Shifts, but characters with capabilities the invincible abilities mentioned above had an easy way to deal with throws and strikes. This gave their defense such a strong advantage that offensive opponents struggled against it. These adjustments seek to correct this issue. These general adjustments are a continuation of previous adjustments. Improvements to While V-Skills and V-Triggers have already been adjusted overall, players infrequently used V-Triggers tend to use one V-Skill and V-Trigger over the other, so we have further and V-Skills strengthened the techniques themselves and the moves that rely on their input. Some characters have been rebalanced in light of previous adjustments. We have buffed characters who were lacking in strength or who were Rebalancing of some largely left alone in previous adjustments. characters Characters with downward adjustments have not had their moves altered significantly; rather, the risks and returns of moves have been properly balanced. Balance Change Overview We've adjusted Nash's close-quarters attack, standing light kick, to yield more of an advantage on hit, and we have further improved Nash's impressive mid to long-distance combat. Standing light kick was previously adjusted to have faster start-up and to be easier to land, but we noticed that it didn't grant the same rewards as it did for other characters. -

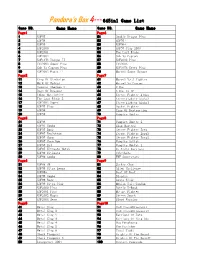

Pandora's Box 4--- 645In1 Game List Game NO

Pandora's Box 4--- 645in1 Game List Game NO. Game Name Game NO. Game Name Page1 Page6 1 KOF97 51 Double Dragon Plus 2 KOF98 52 KOF95+ 3 KOF99 53 KOF96+ 4 KOF2000 54 KOF97 Plus 2003 5 KOF2001 55 The Last Blade 6 KOF2002 56 Snk Vs Capcom 7 KOF10Th Unique II 57 KOF2002 Plus 8 Cth2003 Super Plus 58 Cth2003 9 Snk Vs Capcom Plus 59 KOF10Th Extra Plus 10 KOF2002 Magic II 60 Marvel Super Heroes Page2 Page7 11 King Of Gladiator 61 Marvel Vs S_Fighter 12 Mark Of Wolves 62 Marvel Vs Capcom 13 Samurai Shodown 5 63 X-Men 14 Rage Of Dragons 64 X-Men Vs SF 15 Tokon Matrimelee 65 Street Fighter Alpha 16 The Last Blade 2 66 Streetfighter Alpha2 17 KOF2002 Super 67 Streetfighter Alpha3 18 KOF97 Plus 68 Pocket Fighter 19 KOF94 69 Ring Of Destruction 20 KOF95 70 Vampire Hunter Page3 Page8 21 KOF96 71 Vampire Hunter 2 22 KOF97 Combo 72 Slam Masters 23 KOF97 Boss 73 Street Fighter Zero 24 KOF97 Evolution 74 Street Fighter Zero2 25 KOF97 Chen 75 Street Fighter Zero3 26 KOF97 Chen Bom 76 Vampire Savior 27 KOF97 Lb3 77 Vampire Hunter 2 28 KOF97 Ultimate Match 78 Va Night Warriors 29 KOF98 Ultimate 79 Cyberbots 30 KOF98 Combo 80 WWF Superstars Page4 Page9 31 KOF98 SR 81 Jackie Chan 32 KOF98 Ultra Leona 82 Alien Challenge 33 KOF99+ 83 Best Of Best 34 KOF99 Combo 84 Blandia 35 KOF99 Boss 85 Asura Blade 36 KOF99 Ultra Plus 86 Mobile Suit Gundam 37 KOF2000 Plus 87 Battle K-Road 38 KOF2001 Plus 88 Mutant Fighter 39 KOF2002 Magic 89 Street Smart 40 KOF2004 Hero 90 Blood Warrior Page5 Page10 41 Metal Slug 91 Cadillacs&Dinosaurs 42 Metal Slug 2 92 Cadillacs&Dinosaurs2 -

Cgcopyright 2013 Alexander Jaffe

c Copyright 2013 Alexander Jaffe Understanding Game Balance with Quantitative Methods Alexander Jaffe A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: James R. Lee, Chair Zoran Popovi´c,Chair Anna Karlin Program Authorized to Offer Degree: UW Computer Science & Engineering University of Washington Abstract Understanding Game Balance with Quantitative Methods Alexander Jaffe Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Professor James R. Lee CSE Professor Zoran Popovi´c CSE Game balancing is the fine-tuning phase in which a functioning game is adjusted to be deep, fair, and interesting. Balancing is difficult and time-consuming, as designers must repeatedly tweak parameters and run lengthy playtests to evaluate the effects of these changes. Only recently has computer science played a role in balancing, through quantitative balance analysis. Such methods take two forms: analytics for repositories of real gameplay, and the study of simulated players. In this work I rectify a deficiency of prior work: largely ignoring the players themselves. I argue that variety among players is the main source of depth in many games, and that analysis should be contextualized by the behavioral properties of players. Concretely, I present a formalization of diverse forms of game balance. This formulation, called `restricted play', reveals the connection between balancing concerns, by effectively reducing them to the fairness of games with restricted players. Using restricted play as a foundation, I contribute four novel methods of quantitative balance analysis. I first show how game balance be estimated without players, using sim- ulated agents under algorithmic restrictions. -

Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play a Dissertation

The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Todd L. Harper November 2010 © 2010 Todd L. Harper. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play by TODD L. HARPER has been approved for the School of Media Arts and Studies and the Scripps College of Communication by Mia L. Consalvo Associate Professor of Media Arts and Studies Gregory J. Shepherd Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii ABSTRACT HARPER, TODD L., Ph.D., November 2010, Mass Communications The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play (244 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Mia L. Consalvo This dissertation draws on feminist theory – specifically, performance and performativity – to explore how digital game players construct the game experience and social play. Scholarship in game studies has established the formal aspects of a game as being a combination of its rules and the fiction or narrative that contextualizes those rules. The question remains, how do the ways people play games influence what makes up a game, and how those players understand themselves as players and as social actors through the gaming experience? Taking a qualitative approach, this study explored players of fighting games: competitive games of one-on-one combat. Specifically, it combined observations at the Evolution fighting game tournament in July, 2009 and in-depth interviews with fighting game enthusiasts. In addition, three groups of college students with varying histories and experiences with games were observed playing both competitive and cooperative games together. -

Revista Gameblast - 15.Pdf

ÍNDICE De volta aos ringues O rei dos jogos de luta está prestes a tomar a atenção dos jogadores mais uma vez! Isso porque estamos a poucos dias do lançamento do ano da Capcom: Street Fighter V, a luta da noite aqui na Revista GameBlast. Para o aquecimento, vamos revisitar jogos e lutadores da franquia, além de muita coisa sobre o gênero dos jogos de luta. Nos intervalos, confira tudo sobre Mighty No.9, Far Cry Primal e muito mais! Boa leitura! – Rafael Neves BLAST FROM THE PAST Street Fighter III 3rd Strike (PS2) 04 DIRETOR GERAL / PROJETO GRÁFICO Sérgio Estrella PRÉVIA Street Fighter DIRETOR EDITORIAL V (Multi) 10 Rafael Neves DIRETOR DE PAUTAS Alberto Canen PRÉVIA João Pedro Meireles Lucas Pinheiro Silva Mighty No. 9 Pedro Vicente (Multi) 19 DIRETOR DE REVISÃO Alberto Canen PRÉVIA DIRETOR DE Far Cry Primal DIAGRAMAÇÃO (Multi) 25 Breno Madureira REDAÇÃO Dácio Augusto TOP 10 Ítalo Chianca July Dourado Melhores participações Renan Pinheiro em jogos de luta 31 REVISÃO Bruno Alves PERFIL Henrique Minatogawa Luigi Santana M. Bison (Street Fighter) 36 Vitor Tibério DIAGRAMAÇÃO Breno Madureira Bruno Italiani ANÁLISE David Vieira Guilherme Lima Resident Evil Zero Leandro Fernandes ONLINE HD Remaster (Multi) Letícia Fernandes ILUSTRAÇÕES ANÁLISE S. Carlos Sr. Raposo Pony Island (PC) ONLINE CAPA Felipe Araujo gameblast.com.br 2 ÍNDICE HQ Blast: Piada eterna... E receba todas as edições FAÇA SUA ASSINATURA em seu computador, smartphone ou tablet com antecedência, além de brindes, promoções GRÁTIS DA e edições bônus! REVISTA GAMEBLAST! ASSINAR! gameblast.com.br 3 BLAST FROM THE PAST por Renan Pinheiro Revisão: Henrique Minatogawa Diagramação: Bruno Italiani Street Fighter II chegou ao seu auge e quebrou a desconfiança dos fãs mais tradicionais com a inovação da barra de Super lançando a versão definitiva:Super Street Fighter II Turbo. -

Black Characters in the Street Fighter Series |Thezonegamer

10/10/2016 Black characters in the Street Fighter series |TheZonegamer LOOKING FOR SOMETHING? HOME ABOUT THEZONEGAMER CONTACT US 1.4k TUESDAY BLACK CHARACTERS IN THE STREET FIGHTER SERIES 16 FEBRUARY 2016 RECENT POSTS On Nintendo and Limited Character Customization Nintendo has often been accused of been stuck in the past and this isn't so far from truth when you... Aug22 2016 | More > Why Sazh deserves a spot in Dissidia Final Fantasy It's been a rocky ride for Sazh Katzroy ever since his debut appearance in Final Fantasy XIII. A... Aug12 2016 | More > Capcom's first Street Fighter game, which was created by Takashi Nishiyama and Hiroshi Tekken 7: Fated Matsumoto made it's way into arcades from around late August of 1987. It would be the Retribution Adds New Character Master Raven first game in which Capcom's golden boy Ryu would make his debut in, but he wouldn't be Fans of the Tekken series the only Street fighter. noticed the absent of black characters in Tekken 7 since the game's... Jul18 2016 | More > "The series's first black character was an African American heavyweight 10 Things You Can Do In boxer." Final Fantasy XV Final Fantasy 15 is at long last free from Square Enix's The story was centred around a martial arts tournament featuring fighters from all over the vault and is releasing this world (five countries to be exact) and had 10 contenders in total, all of whom were non year on... Jun21 2016 | More > playable. Each character had unique and authentic fighting styles but in typical fashion, Mirror's Edge Catalyst: the game's first black character was an African American heavyweight boxer.