Copyright Issues and Fair Use in Youtube "Let's Plays" and Video Game Livestreams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Poetics of Reflection in Digital Games

© Copyright 2019 Terrence E. Schenold The Poetics of Reflection in Digital Games Terrence E. Schenold A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2019 Reading Committee: Brian M. Reed, Chair Leroy F. Searle Phillip S. Thurtle Program Authorized to Offer Degree: English University of Washington Abstract The Poetics of Reflection in Digital Games Terrence E. Schenold Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Brian Reed, Professor English The Poetics of Reflection in Digital Games explores the complex relationship between digital games and the activity of reflection in the context of the contemporary media ecology. The general aim of the project is to create a critical perspective on digital games that recovers aesthetic concerns for game studies, thereby enabling new discussions of their significance as mediations of thought and perception. The arguments advanced about digital games draw on philosophical aesthetics, media theory, and game studies to develop a critical perspective on gameplay as an aesthetic experience, enabling analysis of how particular games strategically educe and organize reflective modes of thought and perception by design, and do so for the purposes of generating meaning and supporting expressive or artistic goals beyond amusement. The project also provides critical discussion of two important contexts relevant to understanding the significance of this poetic strategy in the field of digital games: the dynamics of the contemporary media ecology, and the technological and cultural forces informing game design thinking in the ludic century. The project begins with a critique of limiting conceptions of gameplay in game studies grounded in a close reading of Bethesda's Morrowind, arguing for a new a "phaneroscopical perspective" that accounts for the significance of a "noematic" layer in the gameplay experience that accounts for dynamics of player reflection on diegetic information and its integral relation to ergodic activity. -

October 24, 2019

APT41 10/24/2019 Report #: 201910241000 Agenda • APT41 • Overview • Industry targeting timeline and geographic targeting • A very brief (recent) history of China • China’s economic goals matter to APT41 because… • Why does APT41 matter to healthcare? • Attribution and linkages Image courtesy of PCMag.com • Weapons • Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) • References • Questions Slides Key: Non-Technical: managerial, strategic and high-level (general audience) Technical: Tactical / IOCs; requiring in-depth knowledge (sysadmins, IRT) TLP: WHITE, ID# 201910241000 2 Overview • APT41 • Active since at least 2012 • Assessed by FireEye to be: • Chinese state-sponsored espionage group • Cybercrime actors conducts financial theft for personal gain • Targeted industries: • Healthcare • High-tech • Telecommunications • Higher education • Goals: • Theft of intellectual property • Surveillance • Theft of money • Described by FireEye as… • “highly-sophisticated” • “innovative” and “creative” TLP: WHITE, ID# 201910241000 3 Industry targeting timeline and geographic targeting Image courtesy of FireEye.com • Targeted industries: • Gaming • Healthcare • Pharmaceuticals • High tech • Software • Education • Telecommunications • Travel • Media • Automotive • Geographic targeting: • France, India, Italy, Japan, Myanmar, the Netherlands, Singapore, South Korea, South Africa, Switzerland, Thailand, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States and Hong Kong TLP: WHITE, ID# 201910241000 4 A very brief (recent) history of China • First half of 20th century, Chinese -

Game Design Und Produktion“

Leseprobe zu „Game Design und Produktion“ von Gunther Rehfeld Print-ISBN: 978-3-446-46315-8 E-Book-ISBN: 978-3-446-46367-7 E-Pub-ISBN: 978-3-446-46645-6 Weitere Informationen und Bestellungen unter http://www.hanser-fachbuch.de/978-3-446-46315-8 sowie im Buchhandel © Carl Hanser Verlag, München Vorwort zur 2. Auflage Seit dem Erscheinen des Buchs vor mehr als sechs Jahren hat sich an der technologischen Front einiges geändert. Anderes ist beim Alten geblieben. So sind VR (Virtual Reality) und AR (Augmented Reality) zurzeit in aller Munde. Zudem nimmt der Vertrieb von Spielen über digitale Plattformen wie Steam immer mehr Raum ein. Die Game-Engines werden immer komplexer, gleichzeitig aber auch effizienter und einfacher zu bedienen. Virtual Reality (VR) ist zurzeit ein viel diskutierter Trend. Auf der anderen Seite ist das, was ein Spiel ausmacht, gleich geblieben. Die Grundlagen des Game Design werden sich ebenso wenig verändern wie der Prozess der Kreativität, der Umgang mit Spielelementen und -mechaniken, der Kern dessen, was eine gute Geschichte ausmacht etc. Sicherlich, immer neue Formate betreten den Markt. Oft als Moden, die 6 Vorwort zur 2. Auflage jedoch nicht nur auf den Bereich von Games (Computerspielen) beschränkt sind. Ein Beispiel hierfür sind die sogenannten Exit- oder Escape-Games. Sie erfreuen sich zurzeit sowohl digital, als auch als analoge Formate einer großen Beliebtheit. Nach wie vor treiben Games als gemeinschaftliche Interaktion die digitalen Märkte an. Mul- tiplayer-Survival-Titel wie Ark:Survival Evolved (Studio Wildcard, 2017), Blockbuster wie Fortnite (Epic Games, 2017) bis hin zu Browser-Games sind immer wieder an den Spitzen der Charts zu finden. -

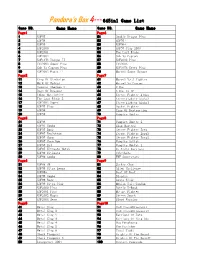

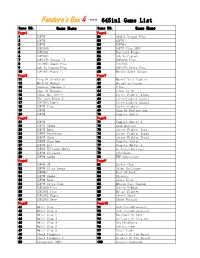

Pandora's Box 4--- 645In1 Game List Game NO

Pandora's Box 4--- 645in1 Game List Game NO. Game Name Game NO. Game Name Page1 Page6 1 KOF97 51 Double Dragon Plus 2 KOF98 52 KOF95+ 3 KOF99 53 KOF96+ 4 KOF2000 54 KOF97 Plus 2003 5 KOF2001 55 The Last Blade 6 KOF2002 56 Snk Vs Capcom 7 KOF10Th Unique II 57 KOF2002 Plus 8 Cth2003 Super Plus 58 Cth2003 9 Snk Vs Capcom Plus 59 KOF10Th Extra Plus 10 KOF2002 Magic II 60 Marvel Super Heroes Page2 Page7 11 King Of Gladiator 61 Marvel Vs S_Fighter 12 Mark Of Wolves 62 Marvel Vs Capcom 13 Samurai Shodown 5 63 X-Men 14 Rage Of Dragons 64 X-Men Vs SF 15 Tokon Matrimelee 65 Street Fighter Alpha 16 The Last Blade 2 66 Streetfighter Alpha2 17 KOF2002 Super 67 Streetfighter Alpha3 18 KOF97 Plus 68 Pocket Fighter 19 KOF94 69 Ring Of Destruction 20 KOF95 70 Vampire Hunter Page3 Page8 21 KOF96 71 Vampire Hunter 2 22 KOF97 Combo 72 Slam Masters 23 KOF97 Boss 73 Street Fighter Zero 24 KOF97 Evolution 74 Street Fighter Zero2 25 KOF97 Chen 75 Street Fighter Zero3 26 KOF97 Chen Bom 76 Vampire Savior 27 KOF97 Lb3 77 Vampire Hunter 2 28 KOF97 Ultimate Match 78 Va Night Warriors 29 KOF98 Ultimate 79 Cyberbots 30 KOF98 Combo 80 WWF Superstars Page4 Page9 31 KOF98 SR 81 Jackie Chan 32 KOF98 Ultra Leona 82 Alien Challenge 33 KOF99+ 83 Best Of Best 34 KOF99 Combo 84 Blandia 35 KOF99 Boss 85 Asura Blade 36 KOF99 Ultra Plus 86 Mobile Suit Gundam 37 KOF2000 Plus 87 Battle K-Road 38 KOF2001 Plus 88 Mutant Fighter 39 KOF2002 Magic 89 Street Smart 40 KOF2004 Hero 90 Blood Warrior Page5 Page10 41 Metal Slug 91 Cadillacs&Dinosaurs 42 Metal Slug 2 92 Cadillacs&Dinosaurs2 -

161 in 1 Neogeo Multigame Cartridge

PCBs : 161 in 1 NeoGeo Multigame Cartridge 161 in 1 NeoGeo Multigame Cartridge Rating: Not Rated Yet Price: Sales price: $99.95 Discount: Ask a question about this product This amazing cart combines 161 of the best Neo Geo games onto a single Neo Geo cartridge. The cartridge uses a built-in OSD (On Screen Display) to first graphically navigate to the game you wish to play. Once finished playing, simply hold down Player 1 START button for 5 seconds to immediately return to the OSD game selection screen again. Description Game List: 1 SNK VS CAPCOM + 2 SNK VS CAPCOM RMX 3 SVC SUPER PLUS 4 KOF 94 5 KOF 94 + 6 KOF 95 7 KOF 95 + 8 KOF 96 9 KOF 96 + 10 KOF 96 EVO 11 KOF 97 12 KOF 97 2003 13 KOF 97 REMIX 14 KOF 97 PLUS 15 KING OF GLADIATOR 16 KOG PLUS 17 KOF 98 18 KOF 98 + 19 KOF 98 ULTIMATE 20 KOF 98 OROCHI 21 KOF 99 22 KOF 99 + 23 KOF 99 CN 24 KOF 2001 25 KOF 2001 PLUS 26 C.T.H.D 27 C.T.H.D SUPER PLUS 28 KOF 2002 29 KOF 2002 MAGIC 30 KOF 2002 MAGIC 2 31 KOF 2002 CN 32 KOF 2002 OROCHI 33 KOF 2002 LUAN 34 KOF 2002 SUPER 35 KOF 2002 SUPER 2 36 KOF 2003 37 KOF 2004 SE PLUS 38 KOF 2004 SE 39 KOF 2004 SMP 40 KOF 10TH 41 KOF 05 UNIQUE 42 KOF 05 UNIQUE 2 43 KOF 10TH EXTRA + 44 RAGE OF DRAGONS 45 RAGE OF DRAGONS + 46 STRIKERS 1945 + 47 STRIKERS 1945 + + 48 AERO FIGHTERS 2 49 AERO FIGHTERS 3 50 METAL SLUG 51 METAL SLUG + 52 METAL SLUG 2 53 METAL SLUG 2 + 54 METAL SLUG 3 55 METAL SLUG 3 + 56 METAL SLUG 4 57 METAL SLUG 4 + 58 METAL SLUG X 59 METAL SLUG X + 60 METAL SLUG 6 61 METAL SLUG 6 + 62 SUPER SIDEKICKS 2 63 SUPER SIDEKICKS 3 64 ULTIMATE 11 65 NEO-GEO -

Video Game Trader Magazine & Price Guide

Winter 2009/2010 Issue #14 4 Trading Thoughts 20 Hidden Gems Blue‘s Journey (Neo Geo) Video Game Flashback Dragon‘s Lair (NES) Hidden Gems 8 NES Archives p. 20 19 Page Turners Wrecking Crew Vintage Games 9 Retro Reviews 40 Made in Japan Coin-Op.TV Volume 2 (DVD) Twinkle Star Sprites Alf (Sega Master System) VectrexMad! AutoFire Dongle (Vectrex) 41 Video Game Programming ROM Hacking Part 2 11Homebrew Reviews Ultimate Frogger Championship (NES) 42 Six Feet Under Phantasm (Atari 2600) Accessories Mad Bodies (Atari Jaguar) 44 Just 4 Qix Qix 46 Press Start Comic Michael Thomasson’s Just 4 Qix 5 Bubsy: What Could Possibly Go Wrong? p. 44 6 Spike: Alive and Well in the land of Vectors 14 Special Book Preview: Classic Home Video Games (1985-1988) 43 Token Appreciation Altered Beast 22 Prices for popular consoles from the Atari 2600 Six Feet Under to Sony PlayStation. Now includes 3DO & Complete p. 42 Game Lists! Advertise with Video Game Trader! Multiple run discounts of up to 25% apply THIS ISSUES CONTRIBUTORS: when you run your ad for consecutive Dustin Gulley Brett Weiss Ad Deadlines are 12 Noon Eastern months. Email for full details or visit our ad- Jim Combs Pat “Coldguy” December 1, 2009 (for Issue #15 Spring vertising page on videogametrader.com. Kevin H Gerard Buchko 2010) Agents J & K Dick Ward February 1, 2009(for Issue #16 Summer Video Game Trader can help create your ad- Michael Thomasson John Hancock 2010) vertisement. Email us with your requirements for a price quote. P. Ian Nicholson Peter G NEW!! Low, Full Color, Advertising Rates! -

CTIN 483 Intro to Game Development Syllabus 2013-1

Introduction to Game Development – Spring, 2013 Syllabus USC School of Cinematic Arts, CTIN 483 (Sections 18354 & 18355) For any class questions, send email to: [email protected] Instructor: Student Assistant: Jeremy Gibson Will Hellwarth (434) 321-8624 (310) 422-3054 [email protected] [email protected] Course Rationale: Being a game designer requires an understanding of several different things, just a few of which are psychology, systems, fun, and storytelling. Each designer has different levels of expertise in each of these areas, and some only excel in one or two, but one thing that all designers need is the ability to communicate their ideas to others. Because games are a medium which, for the most part, must be experienced to be understood, rapid prototyping is often the best possible way to communicate your design ideas to others, and the ability of game designers to prototype can be thought of as equivalent to the ability of cinematographers to sketch; it's not the core skill of game design, but it does make it drastically easier for a game designer to communicate. This course will teach you the basic knowledge you need to be able to create digital prototypes of your own ideas. While you should not expect to come out of this course a great programmer, you will come out a better designer. This course is also required preparation for CTIN 484: Intermediate Game Development, in which students work in pairs to create a single, released game by the end of the semester. Course Description: This production class is focused on rapidly developing game prototypes. -

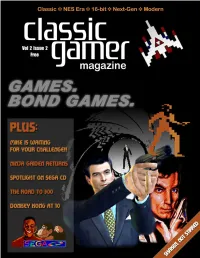

Cgm V2n2.Pdf

Volume 2, Issue 2 July 2004 Table of Contents 8 24 Reset 4 Communist Letters From Space 5 News Roundup 7 Below the Radar 8 The Road to 300 9 Homebrew Reviews 11 13 MAMEusements: Penguin Kun Wars 12 26 Just for QIX: Double Dragon 13 Professor NES 15 Classic Sports Report 16 Classic Advertisement: Agent USA 18 Classic Advertisement: Metal Gear 19 Welcome to the Next Level 20 Donkey Kong Game Boy: Ten Years Later 21 Bitsmack 21 Classic Import: Pulseman 22 21 34 Music Reviews: Sonic Boom & Smashing Live 23 On the Road to Pinball Pete’s 24 Feature: Games. Bond Games. 26 Spy Games 32 Classic Advertisement: Mafat Conspiracy 35 Ninja Gaiden for Xbox Review 36 Two Screens Are Better Than One? 38 Wario Ware, Inc. for GameCube Review 39 23 43 Karaoke Revolution for PS2 Review 41 Age of Mythology for PC Review 43 “An Inside Joke” 44 Deep Thaw: “Moortified” 46 46 Volume 2, Issue 2 July 2004 Editor-in-Chief Chris Cavanaugh [email protected] Managing Editors Scott Marriott [email protected] here were two times a year a kid could always tures a firsthand account of a meeting held at look forward to: Christmas and the last day of an arcade in Ann Arbor, Michigan and the Skyler Miller school. If you played video games, these days writer's initial apprehension of attending. [email protected] T held special significance since you could usu- Also in this issue you may notice our arti- ally count on getting new games for Christmas, cles take a slight shift to the right in the gaming Writers and Contributors while the last day of school meant three uninter- timeline. -

Le Jeu Vidéo Sur Youtube : Historique De La Captation Et De La Diffusion Du Jeu Vidéo

Université de Montréal Le jeu vidéo sur YouTube : historique de la captation et de la diffusion du jeu vidéo par Francis Lavigne Département d’histoire de l’art et d’études cinématographiques Faculté des arts et des sciences Mémoire présenté en vue de l’obtention du grade de M.A. en études cinématographiques option études du jeu vidéo Août 2017 © Francis Lavigne, 2017 Résumé Ce mémoire s’intéresse à la captation audiovisuelle et aux pratiques de commentaires sur le jeu vidéo. Tout d’abord, nous remettons en contexte l’émergence de ce type de production à l’aide d’une analyse historique de divers formats de diffusion (à la télévision, à l’aide de vidéocassettes, dans les suppléments de magazines et sur Internet). Ensuite, nous détaillons les limites et affordances de la plateforme participative YouTube. Puis, nous rattachons les commentaires de jeux vidéo aux concepts de boniment, de performance et de double performance. Enfin, nous analysons quatre genres de vidéos présents sur YouTube : les machinimas, les speedruns, les longplays et les let’s plays. Mots-clés Jeu vidéo, machinima, longplay, let’s play, speedrun, YouTube, boniment, commentaire, double performance i Abstract This research is aimed to understand the audiovisual recording and commentary practices of video games. First of all, we do a contextualisation of these types of production through a historical analysis of the way theses videos were diffused (from televised shows, to VHS, magazines’ bonuses, and on the Internet). After, we detail the limits and affordances of the YouTube sharing platform. Then, we create links between the commentary of video game and the concepts of film lecturer, performance and double performance. -

Pandora's Box 4 --- 645In1 Game List Game NO

Pandora's Box 4 --- 645in1 Game List Game NO. Game Name Game NO. Game Name Page1 Page6 1 KOF97 51 Double Dragon Plus 2 KOF98 52 KOF95+ 3 KOF99 53 KOF96+ 4 KOF2000 54 KOF97 Plus 2003 5 KOF2001 55 The Last Blade 6 KOF2002 56 Snk Vs Capcom 7 KOF10Th Unique II 57 KOF2002 Plus 8 Cth2003 Super Plus 58 Cth2003 9 Snk Vs Capcom Plus 59 KOF10Th Extra Plus 10 KOF2002 Magic II 60 Marvel Super Heroes Page2 Page7 11 King Of Gladiator 61 Marvel Vs S_Fighter 12 Mark Of Wolves 62 Marvel Vs Capcom 13 Samurai Shodown 5 63 X-Men 14 Rage Of Dragons 64 X-Men Vs SF 15 Tokon Matrimelee 65 Street Fighter Alpha 16 The Last Blade 2 66 Streetfighter Alpha2 17 KOF2002 Super 67 Streetfighter Alpha3 18 KOF97 Plus 68 Pocket Fighter 19 KOF94 69 Ring Of Destruction 20 KOF95 70 Vampire Hunter Page3 Page8 21 KOF96 71 Vampire Hunter 2 22 KOF97 Combo 72 Slam Masters 23 KOF97 Boss 73 Street Fighter Zero 24 KOF97 Evolution 74 Street Fighter Zero2 25 KOF97 Chen 75 Street Fighter Zero3 26 KOF97 Chen Bom 76 Vampire Savior 27 KOF97 Lb3 77 Vampire Hunter 2 28 KOF97 Ultimate Match 78 Va Night Warriors 29 KOF98 Ultimate 79 Cyberbots 30 KOF98 Combo 80 WWF Superstars Page4 Page9 31 KOF98 SR 81 Jackie Chan 32 KOF98 Ultra Leona 82 Alien Challenge 33 KOF99+ 83 Best Of Best 34 KOF99 Combo 84 Blandia 35 KOF99 Boss 85 Asura Blade 36 KOF99 Ultra Plus 86 Mobile Suit Gundam 37 KOF2000 Plus 87 Battle K-Road 38 KOF2001 Plus 88 Mutant Fighter 39 KOF2002 Magic 89 Street Smart 40 KOF2004 Hero 90 Blood Warrior Page5 Page10 41 Metal Slug 91 Cadillacs&Dinosaurs 42 Metal Slug 2 92 Cadillacs&Dinosaurs2 -

SNK 138 in 1 GAME LIST

SNK 138 in 1 GAME LIST Special function 1. Each game to Hide 2. Screen images show on the game list right hand side, with a better understanding of game 3. Each game to individual adjustment difficulty and life 4. No coin cannot select any game, Insert coin than select the game Page 1 Page 6 Page 11 KOF2002 MAGIC II ART OF FIGHTING 2 PREHISTORIC ISLE 2 KOF97 ART OF FIGHTING 3 BLAZING STAR KOF98 SAMURAI SHODOWN 2 + ALPHA MISSION II KOF99 SAMURAI SHODOWN 3 + LAST RESORT KOF2001 SAMURAI SHODOWN 4 + ANDRO DUNOS KOF2002 KOF95 + CAPTAIN TOMADAY CTH2003 KOF96 + AERO FIGHTERS 2 KOF2004 SE KOF97 REMIX AERO FIGHTERS 3 KOF2005 UNIQUE II KOF10th EXTRA PLUS ZED BLADE KING OF GLADIATOR SNK VS CAPCOM REMIX PUZZLED JOY JOY KID Page 2 Page 7 Page 12 KOF2002 SUPER METAL SLUG PUZZLE BOBBLE KOF10th UNIQUE METAL SLUG 2 PUZZLE BOBBLE 2 SVC CHAOS PLUS METAL SLUG 3 PUZZLE DE PON! MARK OF THE WOLVES METAL SLUG 4 PUZZLE DE PON!+ THE LAST BLADE METAL SLUG 5 MAGICAL DROP II THE LAST BLADE 2 METAL SLUG 6 MAGICAL DROP III SAMURAI V SPECIAL SHOCK TROOPERS POP’N BOUNCE TOKON MATRIMELEE SHOCK TROOPERS 2 PANIC BOMBER RAGE OF DRAGONS LANSQUENET 2004 MONEY PUZZLE EX DOUBLE DRAGON PLUS NAM-1975 GHOSTLOP Page 3 Page 8 Page 13 KOF94 SPIN MASTER SUPER SIDEKICKS KOF95 BLUE’S JOURNEY SUPER SIDEKICKS 2 KOF96 GANRYU SUPER SIDEKICKS 3 KOF97 PLUS EIGHT MAN 8 THE ULTIMATE 11 KOF98 ULTIMATE MATCH NINJA COMMANDO NEOGEO CUP 98 KOF99 + ROBO ARMY TECMO WORLD 96 KOF2001 PLUS MUTATION NATION GOAL!GOAL!GOAL! KOF2002 MAGIC NINJA COMBAT STREET HOOP CTH2003 SUPER PLUS CYBER-LIP NEO TURF MASTERS -

Motor Para Videojuegos En HTML5, Basados En Tiles

EDITOR WEB UPC Commons Motor para videojuegos en HTML5, basados en tiles Autor: Rodolfo Núñez del Río Dir ector/Ponente : Lluís Solano Albajés 21/01/2014 1 EDITOR WEB 2 EDITOR WEB Índice Índice de figuras ............................................................................................................................................... 6 0. Prólogo ......................................................................................................................................................... 9 1. Introducción ........................................................................................................................................... 9 1.1. Descripción del proyecto ........................................................................................................... 9 1.2. Objetivos ....................................................................................................................................... 10 1.3. Estructura del proyecto ............................................................................................................ 11 2. Evolución hasta Game Engines ..................................................................................................... 11 2.1. 1950 - 1960: Antecedentes ................................................................................................... 11 2.2. 1970: Primeras recreativas .................................................................................................... 14 2.3. 1980 -1990: Los 8 y 16 bits .................................................................................................