Inspiring Community Connection to Mary River Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GYMPIE GYMPIE 0 5 10 Km

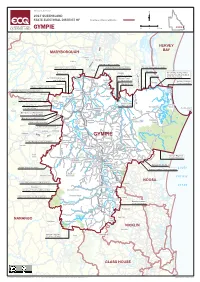

Electoral Act 1992 N 2017 QUEENSLAND STATE ELECTORAL DISTRICT OF Boundary of Electoral District GYMPIE GYMPIE 0 5 10 km HERVEY Y W H BAY MARYBOROUGH Pioneers Rest Owanyilla St Mary E C U Bauple locality boundary R Netherby locality boundary B Talegalla Weir locality boundary Tin Can Bay locality boundary Tiaro Mosquito Ck Barong Creek T Neerdie M Tin Can Bay locality meets in A a n locality boundary R Tinnanbar locality and Great r a e Y Kauri Ck Riv Sandy Strait locality Lot 125 SP205635 and B Toolara Forest O Netherby Lot 19 LX1269 Talegalla locality boundary R O Gympie Regional Weir U Tinnabar Council boundary Mount Urah Big Sandy Ck G H H Munna Creek locality boundary Bauple y r a T i n Inskip M Gundiah Gympie Regional Council boundary C r C Point C D C R e a Caloga e n Marodian k Gootchie O B Munna Creek Bauple Forest O Glenbar a L y NP Paterson O Glen Echo locality boundary A O Glen Echo G L Grongah O A O NP L Toolara Forest Lot 1 L371017 O Rainbow O locality boundary W Kanyan Tin Can Bay Beach Glenwood Double Island Lot 648 LX2014 Kanigan Tansey R Point Miva Neerdie D Wallu Glen Echo locality boundary Theebine Lot 85 LX604 E L UP Glen Echo locality boundary A RD B B B R Scotchy R Gunalda Cooloola U U Toolara Forest C Miva locality boundary Sexton Pocket C Cove E E Anderleigh Y Mudlo NP A Sexton locality boundary Kadina B Oakview Woolooga Cooloola M Kilkivan a WI r Curra DE Y HW y BA Y GYMPIE CAN Great Sandy NP Goomboorian Y A IN Lower Wonga locality boundary Lower Wonga Bells Corella T W Cinnabar Bridge Tamaree HW G Oakview G Y -

A Native Title Information Talk Delivered at Fernvale Futures on 22 February 2014. Tim Wishart Slide 1 I Acknowledge and Offer M

A Native Title Information Talk Delivered at Fernvale Futures on 22 February 2014. Tim Wishart Slide 1 I acknowledge and offer my respect to the country on which we meet and to the Traditional Owners of this country and to their Old People and Elders. The organisation for which I work, Queensland South Native Title Services is a native title service provider recognised and funded by the Federal Government under the Native Title Act (1993). Slide 2 The area for which QSNTS has statutory recognition under the Native Title Act covers an area spanning Queensland, along the New South Wales border from the Coral Sea to the South Australian border, north to about 250 kilometres north of Mt Isa and running diagonally south eastwards to the coast, marginally south of Sarina. Slide 3 I ought to say that views and opinions expressed are mine and are not necessarily reflective of corporate views or policy of QSNTS. In this conversation I will refer to the Native Title Act as ‘the Act’. But in the consciousness of Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander society, the expression “the Act” is often a reference to The Aboriginal Protection and Restrictions of the Sale of Opium Act 1897. That legislation was an Act of the Queensland Parliament. As a result of dispersal, malnutrition, use of opium and diseases, all a consequence of European incursion into traditional lands coupled with the attempted genocide that came with that incursion, it was widely believed in Queensland that Aborigines were members of a 'dying race'. In 1894 pressure from some quarters of the community saw the Queensland Government commission Archibald Meston to look at what had conveniently, for the colonising power, become the plight of Aboriginal people. -

Many Voices Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages Action Plan

Yetimarala Yidinji Yi rawarka lba Yima Yawa n Yir bina ach Wik-Keyangan Wik- Yiron Yam Wik Pa Me'nh W t ga pom inda rnn k Om rungu Wik Adinda Wik Elk Win ala r Wi ay Wa en Wik da ji Y har rrgam Epa Wir an at Wa angkumara Wapabura Wik i W al Ng arra W Iya ulg Y ik nam nh ar nu W a Wa haayorre Thaynakwit Wi uk ke arr thiggi T h Tjung k M ab ay luw eppa und un a h Wa g T N ji To g W ak a lan tta dornd rre ka ul Y kk ibe ta Pi orin s S n i W u a Tar Pit anh Mu Nga tra W u g W riya n Mpalitj lgu Moon dja it ik li in ka Pir ondja djan n N Cre N W al ak nd Mo Mpa un ol ga u g W ga iyan andandanji Margany M litja uk e T th th Ya u an M lgu M ayi-K nh ul ur a a ig yk ka nda ulan M N ru n th dj O ha Ma Kunjen Kutha M ul ya b i a gi it rra haypan nt Kuu ayi gu w u W y i M ba ku-T k Tha -Ku M ay l U a wa d an Ku ayo tu ul g m j a oo M angan rre na ur i O p ad y k u a-Dy K M id y i l N ita m Kuk uu a ji k la W u M a nh Kaantju K ku yi M an U yi k i M i a abi K Y -Th u g r n u in al Y abi a u a n a a a n g w gu Kal K k g n d a u in a Ku owair Jirandali aw u u ka d h N M ai a a Jar K u rt n P i W n r r ngg aw n i M i a i M ca i Ja aw gk M rr j M g h da a a u iy d ia n n Ya r yi n a a m u ga Ja K i L -Y u g a b N ra l Girramay G al a a n P N ri a u ga iaba ithab a m l j it e g Ja iri G al w i a t in M i ay Giy L a M li a r M u j G a a la a P o K d ar Go g m M h n ng e a y it d m n ka m np w a i- u t n u i u u u Y ra a r r r l Y L a o iw m I a a G a a p l u i G ull u r a d e a a tch b K d i g b M g w u b a M N n rr y B thim Ayabadhu i l il M M u i a a -

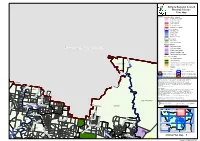

Gympie Regional Council Planning Scheme Zone Map Zoning Plan Map 4

Gympie Regional Council Planning Scheme Zone Map ZONES Residential zones category Character Residential Residential Living Rural Residential Residential Choice Tourist Accommodation Centre zones category Principal Centre District Centre Local Centre Specialised Centre Recreation category Open Space Sport and Recreation Industry category High Impact Industry Fraser Coast Regional Council Low Impact Industry Medium Impact Industry Industry Investigation area Waterfront and Marine Industry B I G Other zones category S A N Community Purposes D Y C Extractive Industry R E E K Environmental Management and Conservation TUAN FOREST Limited Development (Constrained Land) Township Rural Road TINA N Proposed Highway Zone Precinct Boundary A C ! ! R ! E ! EK DCDB ver. 05 June 2012 ! Suburb or Locality Boundary Waterbodies & Waterways Local Government Boundary Disclaimer While every care is taken to ensure the accuracy of this map, Gympie Regional Council makes no representations or warranties about its accuracy, reliability, completeness or suitability for any particular purpose and disclaims all responsibility and all liability (including without limitation, MUNNA CREEK MUNNA CREEK liability in negligence) for all expenses, losses, damage (including indirect or consequential damage) and costs which might incur as a result of the data being inaccurate or incomplete in any way and D A K for any reason. O E R E © Copyright Gympie Regional Council 2012 C R S ULIRRAH EY L D Cadastre Disclaimer: L A U THEEBINE Despite Department of Environment and Resource Management (DERM)'s best efforts,DERM makes no A O representations or warranties in relation to the Information, and, to the extent permitted by law, C R exclude or limit all warranties relating to correctness, accuracy, reliability, completeness or currency E I and all liability for any direct, indirect and consequential costs, losses, damages and expenses incurred P in any way (including but not limited to that arising from negligence) in connection with any use of or M Y reliance on the Information. -

Mary River Catchment Crawl 4 and 5 October 2016

Mary River Catchment Crawl 4th and 5th October 2016 Catchment crawl participants: Brad Wedlock, Caitlin Mill, Tanzi Smith, Jess Dean, Shaun Fisher, Ian Mackay, Ruth Hutchison, Matt Tattam, Kevin Jackson Introduction During the Mary River Month celebrations, the Mary River Catchment Coordinating Committee once again conducted its 8th annual Catchment Crawl on October 4th and 5th, 2016. The Catchment Crawls are designed to provide a snapshot of water quality along the Mary River. Water quality parameters are measured in an effort to gain insight to trends associated with cumulative effects and any other changes along the catchment area. On day one, testing begins in the upper reaches of the catchment, followed by a second day of testing in the lower reaches of the river and its tributaries, right out to the river mouth. A total of 14 freshwater sites were sampled along the main trunk of the Mary River, along with seven sites in several upper and lower tributaries for a total of 21 sites. The tributaries sampled include Six Mile Creek, Widgee Creek, Wide Bay Creek, Munna Creek and Tinana Creek. Sampling occurred across all three local government areas in the catchment. Figure 1 shows a map of all sites sampled during the 2016 catchment crawl. Creek junctions with the Mary River were targeted for sampling in order to gather information on the effects of tributaries flowing into the river. At each sampling site, a standard water test encompassing temperature, dissolved oxygen, electrical conductivity, pH and turbidity was performed. In addition, a sample was taken at each site in accordance with DSITI protocol to be tested for nutrients and total suspended solids. -

Mary River Environmental Values and Water Quality Objectives Basin No

ATTACHMENT 4 Attachment 4, Item 3, Planning & Organisation Committee Agenda, 2 February 2016 Environmental Protection (Water) Policy 2009 Mary River environmental values and water quality objectives Basin No. 138, including all tributaries of the Mary River July 2010 Document Set ID: 20002123 Version: 1, Version Date: 21/12/2015 Prepared by: Water Quality & Ecosystem Health Policy Unit Department of Environment and Resource Management © State of Queensland (Department of Environment and Resource Management) 2010 This publication is available in alternative formats (including large print and audiotape) on request. Contact (07) 322 48412 or email <[email protected]> July 2010 Document Ref Number Document Set ID: 20002123 Version: 1, Version Date: 21/12/2015 Main parts of this document and what they contain • Scope of waters covered Introduction • Key terms / how to use document (section 1) • Links to WQ plan (map) • Mapping / water type information • Further contact details • Amendment provisions • Source of EVs for this document Environmental Values • Table of EVs by waterway (EVs - section 2) - aquatic ecosystem - human use • Any applicable management goals to support EVs • How to establish WQOs to protect Water Quality Objectives all selected EVs (WQOs - section 3) • WQOs in this document, for - aquatic ecosystem EV - human use EVs • List of plans, reports etc containing Ways to improve management actions relevant to the water quality waterways in this area (section 4) • Definitions of key terms including an Dictionary explanation table of all (section 5) environmental values • An accompanying map that shows Accompanying WQ Plan water types, levels of protection and (map) other information contained in this document iii Document Set ID: 20002123 Version: 1, Version Date: 21/12/2015 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ -

The Future of World Heritage in Australia

Keeping the Outstanding Exceptional: The Future of World Heritage in Australia Editors: Penelope Figgis, Andrea Leverington, Richard Mackay, Andrew Maclean, Peter Valentine Editors: Penelope Figgis, Andrea Leverington, Richard Mackay, Andrew Maclean, Peter Valentine Published by: Australian Committee for IUCN Inc. Copyright: © 2013 Copyright in compilation and published edition: Australian Committee for IUCN Inc. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Figgis, P., Leverington, A., Mackay, R., Maclean, A., Valentine, P. (eds). (2012). Keeping the Outstanding Exceptional: The Future of World Heritage in Australia. Australian Committee for IUCN, Sydney. ISBN: 978-0-9871654-2-8 Design/Layout: Pixeldust Design 21 Lilac Tree Court Beechmont, Queensland Australia 4211 Tel: +61 437 360 812 [email protected] Printed by: Finsbury Green Pty Ltd 1A South Road Thebarton, South Australia Australia 5031 Available from: Australian Committee for IUCN P.O Box 528 Sydney 2001 Tel: +61 416 364 722 [email protected] http://www.aciucn.org.au http://www.wettropics.qld.gov.au Cover photo: Two great iconic Australian World Heritage Areas - The Wet Tropics and Great Barrier Reef meet in the Daintree region of North Queensland © Photo: K. Trapnell Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the chapter authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the editors, the Australian Committee for IUCN, the Wet Tropics Management Authority or the Australian Conservation Foundation or those of financial supporter the Commonwealth Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. -

Mary River Environmental Values and Water Quality Objectives (Plan)

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! M A R Y R I V E R , I N C L U D I N G A L L T R I B U T A R I E S O F T H E R I V E! R ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Basin 138 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 152°E 152°20'E ! 152°40'E 153°E ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! H E R V E Y B AY ! ! ! B ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Grego R ! ! ry i ! ! v u er ! ! ! ! ! ! ! r ! ! ! ! CORDALBA ! n ! ! ! ! ! WALKERS ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! e ! ! ! POINT ! Environmental Protection (Water) Policy 2009 S ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! t ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! t t ! ! ! o ! ! Users must refer to plans WQ1372 k c ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! k ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! e ! y ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! R ! r e a and WQ1402 for information on South-east Queensland Map Series ! r ! i d ! ! C v BURRUM -

Surface Water Ambient Network (Water Quality) 2020-21

Surface Water Ambient Network (Water Quality) 2020-21 July 2020 This publication has been compiled by Natural Resources Divisional Support, Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy. © State of Queensland, 2020 The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. Note: Some content in this publication may have different licence terms as indicated. For more information on this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. The Queensland Government shall not be liable for technical or other errors or omissions contained herein. The reader/user accepts all risks and responsibility for losses, damages, costs and other consequences resulting directly or indirectly from using this information. Summary This document lists the stream gauging stations which make up the Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy (DNRME) surface water quality monitoring network. Data collected under this network are published on DNRME’s Water Monitoring Information Data Portal. The water quality data collected includes both logged time-series and manual water samples taken for later laboratory analysis. Other data types are also collected at stream gauging stations, including rainfall and stream height. Further information is available on the Water Monitoring Information Data Portal under each station listing. -

The Freshwater Crayfish (Family Parastacidae) of Queensland

AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS Riek, E. F., 1951. The freshwater crayfish (family Parastacidae) of Queensland. Records of the Australian Museum 22(4): 368–388. [30 June 1951]. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.22.1951.615 ISSN 0067-1975 Published by the Australian Museum, Sydney nature culture discover Australian Museum science is freely accessible online at http://publications.australianmuseum.net.au 6 College Street, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia 11ft! FRESHWATER CRAYFISH (FAMILY PARASTACIDAE) OF QUEENSLAND WITH AN ApPENDIX DESORIBING OTHlm AV5'lHALIAN SPEClEf'. By E. F. HIEK. (;ommonwealth Scientific and Industrial l~csearch Organization - Divhdon of Entomology, Canberra, A.C.T. (Figures 1-13.) Freshwater crayfish occur in almost every body of fresh water from artificial damfl and natural billabongs (I>tanding water) to headwater creeks and large rivers (flowing water). Generally the species are of considerable size and therefore easily collected, but even so many of the larger forms are unknown scientifically. This paper deals with all the species that have been collected from Queensland. It also includes a few species from New South Wales and other States. No doubt additional species will be found and some of the mOre variable series, at present included under the one specific namc, will be further subdivided. From Queensland nine species are described as new, making a total of seventeen species (of three genera) recorded from that State. The type localities of all but two of these species are in Queensland but some are not restricted to the State. Clark's 1936 and subsequent papers have been used as the basis for further taxonomic studies of the Australian freshwater crayfish. -

Inner Brisbane Heritage Walk/Drive Booklet

Engineering Heritage Inner Brisbane A Walk / Drive Tour Engineers Australia Queensland Division National Library of Australia Cataloguing- in-Publication entry Title: Engineering heritage inner Brisbane: a walk / drive tour / Engineering Heritage Queensland. Edition: Revised second edition. ISBN: 9780646561684 (paperback) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Brisbane (Qld.)--Guidebooks. Brisbane (Qld.)--Buildings, structures, etc.--Guidebooks. Brisbane (Qld.)--History. Other Creators/Contributors: Engineers Australia. Queensland Division. Dewey Number: 919.43104 Revised and reprinted 2015 Chelmer Office Services 5/10 Central Avenue Graceville Q 4075 Disclaimer: The information in this publication has been created with all due care, however no warranty is given that this publication is free from error or omission or that the information is the most up-to-date available. In addition, the publication contains references and links to other publications and web sites over which Engineers Australia has no responsibility or control. You should rely on your own enquiries as to the correctness of the contents of the publication or of any of the references and links. Accordingly Engineers Australia and its servants and agents expressly disclaim liability for any act done or omission made on the information contained in the publication and any consequences of any such act or omission. Acknowledgements Engineers Australia, Queensland Division acknowledged the input to the first edition of this publication in 2001 by historical archaeologist Kay Brown for research and text development, historian Heather Harper of the Brisbane City Council Heritage Unit for patience and assistance particularly with the map, the Brisbane City Council for its generous local history grant and for access to and use of its BIMAP facility, the Queensland Maritime Museum Association, the Queensland Museum and the John Oxley Library for permission to reproduce the photographs, and to the late Robin Black and Robyn Black for loan of the pen and ink drawing of the coal wharf. -

FLOOD WARNING SYSTEM for the BURNETT RIVER

Bureau Home > Australia > Queensland > Rainfall & River Conditions > River Brochures > Burnett FLOOD WARNING SYSTEM for the BURNETT RIVER This brochure describes the flood warning system operated by the Australian Government, Bureau of Meteorology for the Burnett River. It includes reference information which will be useful for understanding Flood Warnings and River Height Bulletins issued by the Bureau's Flood Warning Centre during periods of high rainfall and flooding. Contained in this document is information about: (Last updated September 2019) Flood Risk Previous Flooding Flood Forecasting Local Information Flood Warnings and Bulletins Interpreting Flood Warnings and River Height Bulletins Flood Classifications Other Links Burnett River at Mundubbera Flood Risk The Burnett River is located on the southern Queensland coast with the mouth of the river sited just north of the City of Bundaberg. The total area of the catchment is about 33,000 square kilometres. The Burnett River rises in the Dawes Range, just north of Monto and flows south through Eidsvold and Mundubbera. Along the way it is joined by the Nogo and Auburn Rivers which drain large areas in the west of the catchment. Just before Mundubbera, the main river is joined by the Boyne River draining areas from the south and then begins its northeasterly journey to the coast. Between Gayndah and Mt Lawless, the Barker-Barambah Creeks system joins the Burnett River. Major flooding in the Burnett River is relatively infrequent. However, under favourable meteorological conditions such as a tropical low pressure system, heavy rainfalls can occur throughout the catchment which can result in significant river level rises and floods.