The Future of World Heritage in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landscape Report Template

MURRAY REGION DESTINATION MANAGEMENT PLAN MURRAY REGIONAL TOURISM www.murrayregionaltourism.com.au AUTHORS Mike Ruzzene Chris Funtera Urban Enterprise Urban Planning, Land Economics, Tourism Planning & Industry Software 389 St Georges Rd, Fitzroy North, VIC 3068 (03) 9482 3888 www.urbanenterprise.com.au © Copyright, Murray Regional Tourism This work is copyright. Apart from any uses permitted under Copyright Act 1963, no part may be reproduced without written permission of Murray Regional Tourism DISCLAIMER Neither Urban Enterprise Pty. Ltd. nor any member or employee of Urban Enterprise Pty. Ltd. takes responsibility in any way whatsoever to any person or organisation (other than that for which this report has been prepared) in respect of the information set out in this report, including any errors or omissions therein. In the course of our preparation of this report, projections have been prepared on the basis of assumptions and methodology which have been described in the report. It is possible that some of the assumptions underlying the projections may change. Nevertheless, the professional judgement of the members and employees of Urban Enterprise Pty. Ltd. have been applied in making these assumptions, such that they constitute an understandable basis for estimates and projections. Beyond this, to the extent that the assumptions do not materialise, the estimates and projections of achievable results may vary. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 5.3. TOURISM PRODUCT STRENGTHS 32 1. INTRODUCTION 10 PART B. DESTINATION MANAGEMENT PLAN FRAMEWORK 34 1.1. PROJECT SCOPE AND OBJECTIVES 10 6. DMP FRAMEWORK 35 1.2. THE REGION 10 6.1. OVERVIEW 35 1.3. INTEGRATION WITH DESTINATION RIVERINA MURRAY 12 7. -

19–27 June 2021 Darwin, Kakadu, Litchfield

DARWIN, KAKADU, LITCHFIELD. 19–27 JUNE 2021 1 MARVEL AT THE BEAUTY OF AUSTRALIA’S TOP END ON OUR BRAND NEW NINE-DAY CYCLING TOUR IN JUNE 2021. Join us in June 2021 as we escape to the Northern Territory’s Top End and immerse ourselves in vast indigenous culture and ride where few have pedalled before. Along the way we’ll traverse World Heritage-listed National Parks, explore mystic waterfalls and gorges, discover histor- ic indigenous artwork and gaze over floodplains, rainforests and wildlife that has to be seen to be believed. With Bicycle Network behind you the entire way, you can expect full on-route support including rest stops, mechani- cal support and a 24-hour on call team if you need us. and to stop for photos and admire the THE RIDING scenery. The times will have you back Total ride distance: 356km at the accommodation ready for activ- ities and evening meals. It also allows We’ll be there to support you along the Bicycle Network team to pack every kilometre. On some days, guests down and set up the following day, will travel on buses from the hotel to plus enjoy the evening with you. a location to start riding. We’ll start together, with a big cheer! The ride will mostly be on sealed sur- faces. There will be the odd bit of dirt There will be signage, rest areas, food, as we enter and exit rest areas, or if water and mechanics along the route. you venture off the route for some ex- And, if it all gets a bit too much, give tra site seeing. -

Many Voices Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages Action Plan

Yetimarala Yidinji Yi rawarka lba Yima Yawa n Yir bina ach Wik-Keyangan Wik- Yiron Yam Wik Pa Me'nh W t ga pom inda rnn k Om rungu Wik Adinda Wik Elk Win ala r Wi ay Wa en Wik da ji Y har rrgam Epa Wir an at Wa angkumara Wapabura Wik i W al Ng arra W Iya ulg Y ik nam nh ar nu W a Wa haayorre Thaynakwit Wi uk ke arr thiggi T h Tjung k M ab ay luw eppa und un a h Wa g T N ji To g W ak a lan tta dornd rre ka ul Y kk ibe ta Pi orin s S n i W u a Tar Pit anh Mu Nga tra W u g W riya n Mpalitj lgu Moon dja it ik li in ka Pir ondja djan n N Cre N W al ak nd Mo Mpa un ol ga u g W ga iyan andandanji Margany M litja uk e T th th Ya u an M lgu M ayi-K nh ul ur a a ig yk ka nda ulan M N ru n th dj O ha Ma Kunjen Kutha M ul ya b i a gi it rra haypan nt Kuu ayi gu w u W y i M ba ku-T k Tha -Ku M ay l U a wa d an Ku ayo tu ul g m j a oo M angan rre na ur i O p ad y k u a-Dy K M id y i l N ita m Kuk uu a ji k la W u M a nh Kaantju K ku yi M an U yi k i M i a abi K Y -Th u g r n u in al Y abi a u a n a a a n g w gu Kal K k g n d a u in a Ku owair Jirandali aw u u ka d h N M ai a a Jar K u rt n P i W n r r ngg aw n i M i a i M ca i Ja aw gk M rr j M g h da a a u iy d ia n n Ya r yi n a a m u ga Ja K i L -Y u g a b N ra l Girramay G al a a n P N ri a u ga iaba ithab a m l j it e g Ja iri G al w i a t in M i ay Giy L a M li a r M u j G a a la a P o K d ar Go g m M h n ng e a y it d m n ka m np w a i- u t n u i u u u Y ra a r r r l Y L a o iw m I a a G a a p l u i G ull u r a d e a a tch b K d i g b M g w u b a M N n rr y B thim Ayabadhu i l il M M u i a a -

6 Day Lake Mungo Tour Itinerary

I T I N E R A R Y 6 Day Lake Mungo & Outback New South Wales Adventure Get set for some adventure on this epic road trip through Outback New South Wales. Travel in a small group of maximum 8 like minded guests, visit the legendary Lake Mungo National Park and experience the Walls of China, home of the 40000 year old Mungo Man. Enjoy amazing country hospitality and incredible Outback Pubs on this 6 day iconic tour departing Sydney. Inclusions Highly qualified and knowledgeable guide All entry fees including a 30 minute scenic joy flight over Lake Mungo Travel in luxury air-conditioned vehicles All touring Breakfast, lunch and dinner each night, (excluding breakfast on day one and Pick up and drop off from Sydney dinner on day 6) location Comprehensive commentary Exclusions Alcoholic & non alcoholic beverages Gratuities Travel insurance (highly recommended) Souvenirs Additional activities not mentioned Snacks Pick Up 7am - Harrington Street entrance of the Four Seasons Hotel, Sydney. Return 6pm, Day 6 - Harrington Street entrance of the Four Seasons Hotel, Sydney. Alternative arrangements can be made a time of booking for additional pick up locations including home address pickups. Legend B: Breakfast L: Lunch D: Dinner Australian Luxury Escapes | 1 Itinerary: Day 1 Sydney to Hay L, D Depart Sydney early this morning crossing the Blue Mountains and heading North West towards the township of Bathurst, Australia’s oldest inland town. We have some time to stop for a coffee and wander up the main street before rejoining the vehicle. Continue west now to the town of Cowra. -

Immersive Small Group Journeys

Immersive Small Group Journeys TASMANIA • ULURU • KAKADU • NEW ZEALAND • MARGARET RIVER 2021–2022 INSPIRINGJOURNEYS.COM The immersive, vast beauty of Australia and New Zealand awaits. You’ll witness the many hues of an outback sunset blend into ochre natural wonders, hear ancient languages spoken and see stories written in the sand. Indulge in native flavours and relax in dwellings nestled within the heart of your destination. This is where your journey begins. Inspiring Journeys is proud to pay respect to the continuation of cultural practices of Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander and Māori peoples. Outback Australia Right: Local guide Peter – Karrke Aboriginal Cultural Experience in Watarrka National Park Start Exploring • 6 Meet our vibrant makers and Start Exploring Awaiting you is a series of creators, and the local storytellers whose passion it is to share with you AUSTRALIA inspiring, life enriching the very best of these unique lands. Delight the senses with exclusive 24 Northern Territory Dreaming 10 days • MNCR culinary experiences and allow The wild majesty of the Top End and the dramatic landscapes of Australia’s Red Centre combine on this unforgettable journey. your expert guide to show you the iconic sights that promise 28 A Journey to the West 7 days • IJWA moments of awe and wonder. Unique Rottnest Island, renowned wine region Margaret River and an enriching Cape Naturaliste Indigenous cultural experience await you. momen ts. Your journey will be expertly curated 32 Outback Australia: The Colour Of Red 5 days • CRUA with no detail forgotten, ensuring Journey to the Red Centre of Australia, and uncover an ancient your adventure is seamless, stress culture that dates back thousands of years. -

Cascades Female Factory South Hobart Conservation Management Plan

Cascades Female Factory South Hobart Conservation Management Plan Cascades Female Factory South Hobart Conservation Management Plan Prepared for Tasmanian Department of Environment, Parks, Heritage and the Arts April 2008 Table of contents Table of contents i List of figures iii List of Tables v Project Team vi Acknowledgements vii Executive Summary ix 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 Background to project 2 1.2 History & Limitations on Approach 2 1.3 Description 3 1.4 Key Reports & References 4 1.5 Heritage listings & controls 12 1.6 Site Management 13 1.7 Managing Heritage Significance 14 1.8 Future Management 15 2.0 Female Factory History 27 2.1 Introduction 27 2.2 South Hobart 28 2.3 Women & Convict Transportation: An Overview 29 2.4 Convict Women, Colonial Development & the Labour Market 30 2.5 The Development of the Cascades Female Factory 35 2.6 Transfer to the Sheriff’s Department (1856) 46 2.7 Burial & Disinterment of Truganini 51 2.8 Demolition and subsequent history 51 2.9 Conclusion 52 3.0 Physical survey, description and analysis 55 3.1 Introduction 55 3.2 Setting & context 56 3.3 Extant Female Factory Yards & Structures 57 3.4 Associated Elements 65 3.5 Archaeological Resource 67 3.6 Analysis of Potential Archaeological Resource 88 3.7 Artefacts & Movable Cultural Heritage 96 4.0 Assessment of significance 98 4.1 Introduction 98 4.2 Brief comparative analysis 98 4.3 Assessment of significance 103 5.0 Conservation Policy 111 5.1 Introduction 111 5.2 Policy objectives 111 LOVELL CHEN i 5.3 Significant site elements 112 5.4 Conservation -

Honeymoon Barefoot

LUXURY LODGES OF AUSTRALIA SUGGESTED ITINERARIES 1 Darwin 2 Kununurra HONEYMOON Alice Springs Ayers Rock (Uluru) 3 4 BAREFOOT Lord Howe Sydney Island TOTAL SUGGESTED NIGHTS: 12 nights Plus a night or two en route where desired or required. Australia’s luxury barefoot paradises are exclusive by virtue of their remoteness, their special location and the small number of guests they accommodate at any one time. They offer privacy, outstanding experiences and a sense of understated luxury and romance to ensure your honeymoon is the most memorable holiday of a lifetime. FROM DARWIN AIRPORT GENERAL AVIATION TAKE A PRIVATE 20MIN FLIGHT TO PRIVATE AIRSTRIP, THEN 15MIN HOSTED DRIVE TO BAMURRU PLAINS. 1 Bamurru Plains Top End, Northern Territory (3 Nights) This nine room camp exudes ‘Wild Bush Luxury’ ensuring that guests are introduced to the sights and sounds of this spectacular environment in style. On the edge of Kakadu National Park, Bamurru Plains, its facilities and 300km² of country are exclusively for the use of its guests - a romantic, privileged outback experience. A selection of must do’s • Airboat tour - A trip out on the floodplain wetlands is utterly exhilarating and the only way to truly experience this key natural environment. Cut the engine and float amongst mangroves and waterlilies which create one of the most romantic natural sceneries possible. • 4WD safaris - An afternoon out with one of the guides will provide a insight to this fragile yet very important environment. • Enjoy the thrill of a helicopter flight and an exclusive aerial experience over the spectacular floodplains and coastline of Northern Australia. -

Discover the Colours of Australia's Outback | 2019/20

2019/20 FEATURING Discover | Sunrise or sunset over Uluru | Kata Tjuta (Olgas) | Remote the colours Plenty Highway | Kings Canyon | Underground mine tours | Ride of Australia’s the Oodnadatta track | Lake Eyre | Flinders Rangers | Kakadu | outback Cairns | Arnhem Land | with Outback Tour Services Also catering to the disability market with ‘off-road wheelchair access’ The remote touring specialists outbacktourservices.com.au About From the director Outback Tour Services At Outback Tour Services, we are proud to offer you a variety of adventurous tour products and services throughout the great Australian Outback. Our own touring products cover a wide range and include budget to luxury tours, Outback Tour Services was formed at the start of specialised and award-winning Disability 2014. Whilst the company itself is new, the owners Camping Tours, and self drive Adventure Rentals. have over 20 years experience in operating adventure camping tours in remote locations. We also operate as a Destination Management Company for a number of local and interstate companies such as With a fleet of around 70 vehicles, ranging from Intrepid/Adventure Tours Australia Group, smaller 4x4 vehicles all the way up to a 55 seat luxury Emu Run, Kings Canyon Resort and many others. coach, our specialist services cater for all remote touring experiences. Through these partnerships we are able to extend our services to offer greater choices, so your "once in a lifetime" Our Services include: experience will suit your pace, comfort » Fully catered and guided tours from level and meet your preferred travelling Alice Springs (other start and finish expectations. locations available) If you are simply looking for a seat on a » Groups can range from small family scheduled tour or interested in any of our charter in a 4x4 vehicle up to our luxury specialised services, please don’t hesitate 46 seat coach to contact our friendly and experienced team who can match you to a product » Self drive 4WD vehicle hire that best fits your brief. -

Broken-Hill-Outback-Guide.Pdf

YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO DESTINATION BROKEN HILL Contents Broken Hill 4 Getting Here & Getting Around 7 History 8 Explore & Discover 16 Arts & Culture 32 Eat & Drink 38 Places to Stay 44 Shopping 54 The Outback 56 Silverton 60 White Cliffs 66 Cameron Corner, Milparinka 72 & Tibooburra Menindee 74 Wilcannia, Tilpa & Louth 78 National Parks 82 Going off the Beaten Track 88 City Map 94 Regional Map 98 Have a safe and happy journey! Your feedback about this guide is encouraged. Every endeavor has been made to ensure that the details appearing in this publication are correct at the time of printing, but we can accept no responsibility for inaccuracies. Photography has been provided by Broken Hill City Council, Broken Heel Festival: 7-9 September 2018 Destination NSW, NSW National Parks & Wildlife, Simon Bayliss and other contributors. This visitor guide has been designed and produced by Pace Advertising Pty. Ltd. ABN 44 005 361 768 P 03 5273 4777, www.pace.com.au, [email protected]. Copyright 2018 Destination Broken Hill. 2 BROKEN HILL & THE OUTBACK GUIDE 2018 3 There is nowhere else quite like Broken Hill, a unique collision of quirky culture with all the hallmarks of a dinky-di town in the Australian outback. A bucket-list destination for any keen BROKEN traveller, Broken Hill is an outback oasis bred by the world’s largest and dominant mining company, BHP (Broken Hill Proprietary), a history HILL Broken Hill is Australia’s first heritage which has very much shaped the town listed city. With buildings like this, it’s today. -

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

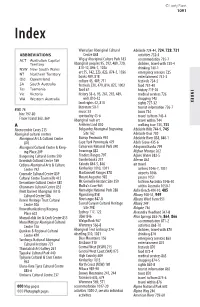

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

The Coast of the Shires of Shark Bay to Exmouth, Gascoyne, Western Australia: Geology, Geological Survey of Western Australia Geomorphology & Vulnerability

The Coast of the Shires of Shark Bay to Exmouth, Gascoyne, Western Australia: Geology, Geomorphology and Vulnerability December 2012 Technical Report Technical The Department of Planning engaged Damara WA Pty Ltd to prepare this report as a background technical guidance document only. Damara conducted this project in conjunction with the Geological Survey of Western Australia. Damara WA Pty Ltd Citation Email: [email protected] Eliot I, Gozzard JR, Eliot M, Stul T and McCormack Tel: (08) 9445 1986 G. (2012) The Coast of the Shires of Shark Bay to Exmouth, Gascoyne, Western Australia: Geology, Geological Survey of Western Australia Geomorphology & Vulnerability. Prepared by Department of Mines and Petroleum Damara WA Pty Ltd and Geological Survey Tel: (08) 9222 3333 of Western Australia for the Department of Planning and the Department of Transport. Cover Photographs Top-left: Perched beach at Vlamingh Head (Photograph: Bob Gozzard. May 2011). Top-right: Climbing dune on the Ningaloo coast (Photograph: Bob Gozzard. May 2011). Bottom-left: Coral Bay (Photograph: Bob Gozzard. May 2011). Bottom-right: Gascoyne River delta at Carnarvon (Photograph: Ian Eliot. May 2011). © State of Western Australia Published by the Western Australian Planning Commission Gordon Stephenson House 140 William Street Perth WA 6000 Disclaimer Locked Bag 2506 This document has been published by the Perth WA 6001 Western Australian Planning Commission. Published December 2012 Any representation, statement, opinion or advice expressed or implied in this website: www.planning.wa.gov.au publication is made in good faith and email: [email protected] on the basis that the government, its tel: 08 655 19000 employees and agents are not liable for fax: 08 655 19001 any damage or loss whatsoever which National Relay Service: 13 36 77 may occur as a result of action taken or infoline: 1800 626 477 not taken, as the case may be, in respect of any representation, statement, opinion Western Australian Planning Commission owns all or advice referred to herein. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

New South Wales Legislative Assembly PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Fifty-Seventh Parliament First Session Wednesday, 17 June 2020 Authorised by the Parliament of New South Wales TABLE OF CONTENTS Bills ......................................................................................................................................................... 2595 Crimes Amendment (Special Care Offences) Bill 2020 ..................................................................... 2595 Mental Health and Cognitive Impairment Forensic Provisions Bill 2020 ......................................... 2595 Returned .......................................................................................................................................... 2595 Law Enforcement Conduct Commission Amendment Bill 2020 ....................................................... 2595 First Reading ................................................................................................................................... 2595 Announcements ...................................................................................................................................... 2595 Thought Leadership Event .................................................................................................................. 2595 Notices .................................................................................................................................................... 2595 Presentation ........................................................................................................................................