Iconic Lands: Wilderness As a Reservation Criterion for World Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summary of Road Closures

summary of road closures targa.com.au #TARGA | #TARGAhighcountry#TARGAtasmania | #TARGAtasmania2021 | #TARGAhighcountry2021 LEG ONE – monday 19th April MUNICIPALITY OF MEANDER VALLEY Stage Name: HIGH PLAINS Road closure time: 7:57 – 12:27 Roads Closed Between the following Roads Weetah Road Mitchells Road and East Parkham Road MUNICIPALITY OF LATROBE Stage Name: MORIARTY Road closure time: 8:27 – 12:57 Roads Closed Between the following Roads Valley Field Road Chaple Road and Oppenheims Road Oppenheims Road Valley Field Road and Hermitage Lane Hermitage Lane Oppenheims Road and Bonneys Road Bonneys Lane Hermitage Lane and Moriarty Road CITY OF DEVONPORT AND MUNICIPALITY OF KENTISH Stage Name: PALOONA Road closure time: 10:01 – 14:31 Roads Closed Between the following Roads Buster Road Melrose Road and Melrose Road Melrose Road Buster Road and Paloona Road Paloona Road Melrose Road and Paloona Dam Road Paloona Dam Road Paloona Road and Lake Paloona Road Lake Paloona Road Paloona Dam Road and Lower Barrington Road Stage Name: MT ROLAND Road closure time: 10:42 – 15:12 Roads Closed Between the following Roads Olivers Road Claude Road and Mersey Forest Road Mersey Forest Road Olivers Road and Liena Road MUNICIPALITY OF MEANDER VALLEY Stage Name: GOLDEN VALLEY Road closure time: 11:50 – 16:20 Roads Closed Between the following Roads Highland Lakes Road Golden Valley Road and Haulage Road MUNICIPALITY OF NORTHERN MIDLANDS Stage Name: POATINA Road closure time: 13:01 – 17:31 Roads Closed Between the following Roads Poatina Road Westons Road -

Murchison Highway Upgrades

2012 (No. 26) _______________ PARLIAMENT OF TASMANIA _______________ PARLIAMENTARY STANDING COMMITTEE ON PUBLIC WORKS Murchison Highway Upgrades ______________ Presented to His Excellency the Governor pursuant to the provisions of the Public Works Committee Act 1914. ______________ MEMBERS OF THE COMMITTEE Legislative Council House of Assembly Mr Harriss (Chairman) Mr Booth Mr Hall Mr Brooks Ms White TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 2 BACKGROUND .............................................................................................................. 2 PROJECT COSTS ............................................................................................................ 3 EVIDENCE ...................................................................................................................... 4 DOCUMENTS TAKEN INTO EVIDENCE ......................................................................... 9 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION .................................................................... 9 1 INTRODUCTION To His Excellency the Honourable Peter Underwood, AC, Governor in and over the State of Tasmania and its Dependencies in the Commonwealth of Australia. MAY IT PLEASE YOUR EXCELLENCY The Committee has investigated the following proposals: - Murchison Highway Upgrades and now has the honour to present the Report to Your Excellency in accordance with the Public Works Committee Act 1914. BACKGROUND The Murchison Highway -

Immersive Small Group Journeys

Immersive Small Group Journeys TASMANIA • ULURU • KAKADU • NEW ZEALAND • MARGARET RIVER 2021–2022 INSPIRINGJOURNEYS.COM The immersive, vast beauty of Australia and New Zealand awaits. You’ll witness the many hues of an outback sunset blend into ochre natural wonders, hear ancient languages spoken and see stories written in the sand. Indulge in native flavours and relax in dwellings nestled within the heart of your destination. This is where your journey begins. Inspiring Journeys is proud to pay respect to the continuation of cultural practices of Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander and Māori peoples. Outback Australia Right: Local guide Peter – Karrke Aboriginal Cultural Experience in Watarrka National Park Start Exploring • 6 Meet our vibrant makers and Start Exploring Awaiting you is a series of creators, and the local storytellers whose passion it is to share with you AUSTRALIA inspiring, life enriching the very best of these unique lands. Delight the senses with exclusive 24 Northern Territory Dreaming 10 days • MNCR culinary experiences and allow The wild majesty of the Top End and the dramatic landscapes of Australia’s Red Centre combine on this unforgettable journey. your expert guide to show you the iconic sights that promise 28 A Journey to the West 7 days • IJWA moments of awe and wonder. Unique Rottnest Island, renowned wine region Margaret River and an enriching Cape Naturaliste Indigenous cultural experience await you. momen ts. Your journey will be expertly curated 32 Outback Australia: The Colour Of Red 5 days • CRUA with no detail forgotten, ensuring Journey to the Red Centre of Australia, and uncover an ancient your adventure is seamless, stress culture that dates back thousands of years. -

Wild Yoga on the Franklin River with Rebecca Wildbear

Wild Yoga on the Franklin River with Rebecca Wildbear March 1 – 9, 2019 Yoga • Raft • Soul Journey in Tasmania, Australia A river soul journey that combines yoga, dreamwork, conversations with the more-than-human world, deep imagination, and a rafting trip on the Franklin River. oul yearns to feel the rhythm of Sthe river’s song. Living in river consciousness, what will stir in your imagination? The river follows the natural pull of gravity as it fows over, around, and through the quartzite and limestone gorge. What moves you? Rebecca Wildbear, M.S. On this 9-day journey, you’ll awaken your wild animal body and be invited Rebecca is a river and soul guide, to enter the underworld river of your compassionately helping people tune in to the mysteries that live own life and open to non-ordinary ways within the wild Earth community, of perceiving. Immerse yourself in the Dreamtime, and their own wild presence and wisdom of the river and Nature. She gently ushers people to surrender into the heart of your own the underground river of their greater particular way of belonging to the world. story, so they may surrender to their Enter into a deep love afair with your- soul’s deepest longing and embrace their sacred gifts. A therapist and self as you foat through this ancient wilderness guide since 1997, Rebecca and majestic river canyon and root utilizes her training and experience yourself in relationship with the animate, natural world. Discover life-altering glim- with yoga, meditation, Hakomi, and mers of your greater purpose, unique artistry, and role in the larger Earth community. -

Water Management in the Anthony–Pieman Hydropower Scheme

Water management in the Anthony–Pieman hydropower scheme Pieman Sustainability Review June 2015 FACT SHEET Background The Anthony–Pieman hydropower scheme provides a highly valued and reliable source of electricity. The total water storage of the hydropower scheme is 512 gigalitres and the average annual generation is 2367 gigawatt hours. Construction of the Anthony–Pieman hydropower scheme has resulted in creation of water storages (lakes) and alterations to the natural flow of existing rivers and streams. The Pieman Sustainability Review is a review of operational, social and environmental aspects of the Anthony–Pieman hydropower scheme that are influenced by Hydro Tasmania. This fact sheet elaborates on water management issues presented in the summary report, available at http://www.hydro.com.au/pieman-sustainability-review Water storage levels in the Anthony–Pieman Water levels have been monitored at these storages since hydropower scheme their creation in stages between 1981 and 1991. The Anthony–Pieman hydropower scheme includes eight Headwater storages: Lake Mackintosh and Lake water storages, classified as headwater storages (Lakes Murchison Mackintosh and Murchison), diversion storages (Lakes Lakes Mackintosh and Murchison are the main headwater Henty and Newton and White Spur Pond) and run-of-river storages for the Anthony–Pieman hydropower scheme. storages (Lakes Rosebery, Plimsoll and Pieman). Lakes The water level fluctuates over the entire operating range Murchison, Henty and Newton and White Spur Pond do not from Normal Minimum Operating Level (NMOL) to Full release water directly to a power station; rather they are Supply Level (FSL) (Figures 1, 2). used to transfer water to other storages within the scheme. -

Captain Louis De Freycinet

*Catalogue title pages:Layout 1 13/08/10 2:51 PM Page 1 CAPTAIN LOUIS DE FREYCINET AND HIS VOYAGES TO THE TERRES AUSTRALES *Catalogue title pages:Layout 1 13/08/10 2:51 PM Page 3 HORDERN HOUSE rare books • manuscripts • paintings • prints 77 VICTORIA STREET POTTS POINT NSW 2011 AUSTRALIA TEL (61-2) 9356 4411 FAX (61-2) 9357 3635 [email protected] www.hordern.com CONTENTS Introduction I. The voyage of the Géographe and the Naturaliste under Nicolas Baudin (1800-1804) Brief history of the voyage a. Baudin and Flinders: the official narratives 1-3 b. The voyage, its people and its narrative 4-29 c. Freycinet’s Australian cartography 30-37 d. Images, chiefly by Nicolas Petit 38-50 II. The voyage of the Uranie under Louis de Freycinet (1817-1820) Brief history of the voyage a. Freycinet and King: the official narratives 51-54 b. Preparations and the voyage 55-70 c. Freycinet constructs the narrative 71-78 d. Images of the voyage and the artist Arago’s narrative 79-92 Appendix 1: The main characters Appendix 2: The ships Appendix 3: Publishing details of the Baudin account Appendix 4: Publishing details of the Freycinet account References Index Illustrated above: detail of Freycinet’s sketch for the Baudin atlas (catalogue no. 31) Illustrated overleaf: map of Australia from the Baudin voyage (catalogue no. 1) INTRODUCTION e offer for sale here an important on the contents page). To illuminate with knowledge collection of printed and original was the avowed aim of each of the two expeditions: Wmanuscript and pictorial material knowledge in the widest sense, encompassing relating to two great French expeditions to Australia, geographical, scientific, technical, anthropological, the 1800 voyage under Captain Nicolas Baudin and zoological, social, historical, and philosophical the 1817 voyage of Captain Louis-Claude de Saulces discoveries. -

The Absolute Best Day Walks in Tasmania

FOOTSTEPS WALKING CLUB OF AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND THE ABSOLUTE BEST DAY WALKS IN TASMANIA Thursday 17 March to Sunday 10 April 2022 25 days ex-Hobart (including 2 rest days) (timed to get the best weather and avoid the Tasmanian school holidays) Leader: Phillip Donnell Estimated price: $4995 (excluding airfares) (based on a minimum of 10 participants and subject to currency fluctuations) A comprehensive walking tour covering the whole of Tasmania. Experience a tremendous range of landscapes across 14 national parks, all four coasts, numerous reserves and several wilderness areas. Encounter the wildlife, discover the convict past and enjoy Tassie’s relaxed style! This is a beaut little holiday... PRICE INCLUDES: Accommodation – shared rooms in hotels, cabins, hostels, motels. Transport in a hired minibus, possibly with luggage trailer. All breakfasts and subsidised farewell celebration dinner. Experienced Kiwi trip leader throughout. National Park entry fees. Ferry fares (vehicles and passengers). PRICE DOES NOT INCLUDE: Flights to / from Tasmania (direct flights are now available). Airport transfer fees. Lunches and dinners. Travel insurance. Personal incidentals, excursions, and entry to attractions. Cradle Mountain A “White Knight” at Evercreech Wineglass Bay TASMANIA 2022 ITINERARY DATE POSSIBLE WALK(S) OVERNIGHT HOBART Day 1 Arrival Day Hobart Thursday It is recommended that you fly into Hobart early. 17 March Transfer to the hotel in downtown. Use any free time to explore Hobart: Battery Point, Queen’s Domain, MONA. A wander through the Battery Point historic area of Hobart reveals the delightful original cottages, beautiful stone and brick homes and also the maritime history of this very walkable city. -

Marine Ecology Progress Series 483:117

Vol. 483: 117–131, 2013 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published May 30 doi: 10.3354/meps10261 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Variation in the morphology, reproduction and development of the habitat-forming kelp Ecklonia radiata with changing temperature and nutrients Christopher J. T. Mabin1,*, Paul E. Gribben2, Andrew Fischer1, Jeffrey T. Wright1 1National Centre for Marine Conservation and Resource Sustainability (NCMCRS), Australian Maritime College, University of Tasmania, Launceston, Tasmania 7250, Australia 2Biodiversity Research Group, Climate Change Cluster, University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales 2007, Australia ABSTRACT: Increasing ocean temperatures are a threat to kelp forests in several regions of the world. In this study, we examined how changes in ocean temperature and associated nitrate concentrations driven by the strengthening of the East Australian Current (EAC) will influence the morphology, reproduction and development of the widespread kelp Ecklonia radiata in south- eastern Australia. E. radiata morphology and reproduction were examined at sites in New South Wales (NSW) and Tasmania, where sea surface temperature differs by ~5°C, and a laboratory experiment was conducted to test the interactive effects of temperature and nutrients on E. radiata development. E. radiata size and amount of reproductive tissue were generally greater in the cooler waters of Tasmania compared to NSW. Importantly, one morphological trait (lamina length) was a strong predictor of the amount of reproductive tissue, suggesting that morphological changes in response to increased temperature may influence reproductive capacity in E. radiata. Growth of gametophytes was optimum between 15 and 22°C and decreased by >50% above 22°C. Microscopic sporophytes were also largest between 15 and 22°C, but no sporophytes developed above 22°C, highlighting a potentially critical upper temperature threshold for E. -

Sustainable Murchison 2040 Plan

Sustainable Murchison 2040 Community Plan Regional Framework Plan Prepared for Waratah-Wynyard Council, Circular Head Council, West Coast Council, King Island Council and Burnie City Council Date 21 November 2016 Geografi a Geografia Pty Ltd • Demography • Economics • Spatial Planning +613 9329 9004 | [email protected] | www.geografia.com.au Supported by the Tasmanian Government Geografia Pty Ltd • Demography • Economics • Spatial Planning +613 9329 9004 | [email protected] | www.geografia.com.au 571 Queensberry Street North Melbourne VIC 3051 ABN: 33 600 046 213 Disclaimer This document has been prepared by Geografia Pty Ltd for the councils of Waratah-Wynyard, Circular Head, West Coast, and King Island, and is intended for their use. It should be read in conjunction with the Community Engagement Report, the Regional Resource Analysis and Community Plan. While every effort is made to provide accurate and complete information, Geografia does not warrant or represent that the information contained is free from errors or omissions and accepts no responsibility for any loss, damage, cost or expense (whether direct or indirect) incurred as a result of a person taking action in respect to any representation, statement, or advice referred to in this report. Executive Summary The Sustainable Murchison Community Plan belongs to the people of Murchison, so that they may plan and implement for a sustainable future. Through one voice and the cooperative action of the community, business and government, Murchison can be a place where aspirations are realised. This plan is the culmination of extensive community and stakeholder consultation, research and analysis. It sets out the community vision, principles and strategic objectives for Murchison 2040. -

Groundwaters in Wet, Temperate, Mountainous,Sulphide-Mining Districts

Groundwaters in wet, temperate, mountainous, sulphide-mining districts: delineation of modern fluid flow and predictive modelling for mine closure (Rosebery, Tasmania). by Lee R. Evans B.App.Sci.(Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy UNIVERSITY OF TASMANIA September 2009 Cover Image: Elevated orthogonal view of the 3D Rosebery groundwater model grid looking towards the northeast. i Declaration This thesis contains no material that has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of the candidate’s knowledge and beliefs, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis. Three co-authored conference publications written as part of the present study (Evans et al., 2003; Evans et al., 2004a; and Evans et al., 2004b) are provided in Appendix Sixteen. Lee R. Evans Date: This thesis is to be made available for loan or copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1969 from the date this statement was signed. Lee R. Evans Date: ii Abstract There are as yet few studies of the hydrogeology of sulphide-mining districts in wet, temperate, mountainous areas of the world. This is despite the importance of understanding the influence of hydrogeology on the evolution and management of environmental issues such as acid mine drainage (AMD). There is a need to determine whether the special climatic and geological features of such districts result in distinct groundwater behaviours and compositions which need to be considered in mining impact studies. -

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

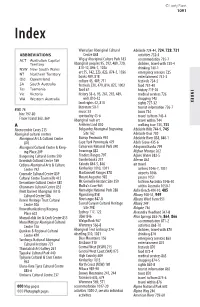

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

The Future of World Heritage in Australia

Keeping the Outstanding Exceptional: The Future of World Heritage in Australia Editors: Penelope Figgis, Andrea Leverington, Richard Mackay, Andrew Maclean, Peter Valentine Editors: Penelope Figgis, Andrea Leverington, Richard Mackay, Andrew Maclean, Peter Valentine Published by: Australian Committee for IUCN Inc. Copyright: © 2013 Copyright in compilation and published edition: Australian Committee for IUCN Inc. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Figgis, P., Leverington, A., Mackay, R., Maclean, A., Valentine, P. (eds). (2012). Keeping the Outstanding Exceptional: The Future of World Heritage in Australia. Australian Committee for IUCN, Sydney. ISBN: 978-0-9871654-2-8 Design/Layout: Pixeldust Design 21 Lilac Tree Court Beechmont, Queensland Australia 4211 Tel: +61 437 360 812 [email protected] Printed by: Finsbury Green Pty Ltd 1A South Road Thebarton, South Australia Australia 5031 Available from: Australian Committee for IUCN P.O Box 528 Sydney 2001 Tel: +61 416 364 722 [email protected] http://www.aciucn.org.au http://www.wettropics.qld.gov.au Cover photo: Two great iconic Australian World Heritage Areas - The Wet Tropics and Great Barrier Reef meet in the Daintree region of North Queensland © Photo: K. Trapnell Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the chapter authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the editors, the Australian Committee for IUCN, the Wet Tropics Management Authority or the Australian Conservation Foundation or those of financial supporter the Commonwealth Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities.