Offshore Oil & Gas in BC: a Chronology of Activity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Columbia Regional Guide Cat

National Marine Weather Guide British Columbia Regional Guide Cat. No. En56-240/3-2015E-PDF 978-1-100-25953-6 Terms of Usage Information contained in this publication or product may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, for personal or public non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, unless otherwise specified. You are asked to: • Exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; • Indicate both the complete title of the materials reproduced, as well as the author organization; and • Indicate that the reproduction is a copy of an official work that is published by the Government of Canada and that the reproduction has not been produced in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada. Commercial reproduction and distribution is prohibited except with written permission from the author. For more information, please contact Environment Canada’s Inquiry Centre at 1-800-668-6767 (in Canada only) or 819-997-2800 or email to [email protected]. Disclaimer: Her Majesty is not responsible for the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in the reproduced material. Her Majesty shall at all times be indemnified and held harmless against any and all claims whatsoever arising out of negligence or other fault in the use of the information contained in this publication or product. Photo credits Cover Left: Chris Gibbons Cover Center: Chris Gibbons Cover Right: Ed Goski Page I: Ed Goski Page II: top left - Chris Gibbons, top right - Matt MacDonald, bottom - André Besson Page VI: Chris Gibbons Page 1: Chris Gibbons Page 5: Lisa West Page 8: Matt MacDonald Page 13: André Besson Page 15: Chris Gibbons Page 42: Lisa West Page 49: Chris Gibbons Page 119: Lisa West Page 138: Matt MacDonald Page 142: Matt MacDonald Acknowledgments Without the works of Owen Lange, this chapter would not have been possible. -

British Columbia Groundfish Fisheries and Their Investigations in 1999

British Columbia Groundfish Fisheries And Their Investigations in 1999 April 2000 Prepared for the 41st Annual Meeting of the Technical Sub- committee of the Canada-United States Groundfish Committee May 9-11, 1999. Nanaimo,B.C. CANADA by M. W. Saunders K. L. Yamanaka Fisheries and Oceans Canada Science Branch Pacific Biological Station Nanaimo, British Columbia V9R 5K6 - 2 - REVIEW OF AGENCY GROUNDFISH RESEARCH, STOCK ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT A. Agency overview Fisheries and Oceans Canada (FOC), Science Branch, operates three facilities in the Pacific Region: the Pacific Biological Station (PBS), the Institute of Ocean Sciences (IOS) and the West Vancouver Laboratory (WVL). These facilities are located in Nanaimo, Sidney and North Vancouver, B.C., respectively. Division Heads at these facilities report to the Regional Director of Science (RDS). Personnel changes within the Region Science Branch in 1999 include the appointments of Dr. Laura Richards as the Acting RDS and Mr. Ted Perry as the Head of the Stock Assessment Division (STAD). The current Division Heads in Science Branch are: Stock Assessment Division Mr. T. Perry Marine Environment and Habitat Science Dr. J. Pringle Ocean Science and Productivity Mr. R. Brown Aquaculture Dr. D. Noakes Groundfish research and stock assessments are conducted primarily in two sections of the Stock Assessment Division, Fish Population Dynamics (Sandy McFarlane, Head) and Assessment Methods (Jeff Fargo, Head). The Assessment Methods Section includes the Fish Ageing Lab. A reorganization is imminent and the plan is to convene a single Groundfish Section and a new Pelagics Section. The section heads are yet to be determined. Management of groundfish resources is the responsibility of the Pacific Region Groundfish Coordinator (Ms. -

Fieldnotes 2021-2022

FIELDNOTES 2021 – 2022 Pacific Science Field Operations Cover illustration: Copper Rockfish (Sebastes caurinus) in an old growth kelp forest covered in Proliferating Anemones (Epiactis prolifera). Queen Charlotte Strait, BC. Photo credit: Pauline Ridings, Fisheries and Oceans Canada. FIELDNOTES 2021 - 2022: DFO Pacific Science Field Operations TABLE OF CONTENT . INTRODUCTION 1 . DFO PACIFIC SCIENCE 2 . SCHEDULED FIELD OPERATIONS: 2021—2022 3 . DID YOU KNOW? 5 . REPORTING RESULTS 6 . ANNEX A PACIFIC SCIENCE ORGANIZATION 7 . ANNEX B FACT SHEET SERIES: 2020—2021 DFO Pacific Science Field Operations 12 . ANNEX C DATASETS PUBLISHED: 2020—2021 18 FIELDNOTES 2021 - 2022: DFO Pacific Science Field Operations INTRODUCTION Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) conducts research and undertakes monitoring surveys of the marine and freshwater environment in support of sustainable fisheries, healthy aquatic ecosystems and living resources, and safe and effective marine services. In an effort to effectively inform and ensure Canadians feel engaged in the delivery of its science mandate, DFO produces Fieldnotes, an annual compendium of planned science field operations in the North Pacific and Arctic oceans, as well as in the coastal and interior waters of British Columbia and Yukon. Fieldnotes aims to: . inform Canadians of research and monitoring programming scheduled for the COVID-19 coming year; . promote the sharing of key information and data in a coordinated, timely, open and One year into the global pandemic, DFO transparent manner in order to encourage remains committed to delivering innovative dialogue and collaboration; science and services to Canadians. provide a platform from which to build and Following the suspension of scientific field nurture fundamentally more inclusive, trust- and respect-based relationships with all operations in the spring of 2020, DFO has Canadians; since resumed much of its field programming. -

Skeena River Estuary Juvenile Salmon Habitat

Skeena River Estuary Juvenile Salmon Habitat May 21, 2014 Research carried out by Ocean Ecology 1662 Parmenter Ave. Prince Rupert, BC V8J 4R3 Telephone: (250) 622-2501 Email: [email protected] Skeena River Estuary Skeena River Estuary Juvenile Salmon Habitat Skeena Wild Conservation Trust 4505 Greig Avenue Terrace, B.C. V8G 1M6 and Skeena Watershed Conservation Coalition PO Box 70 Hazelton, B.C. V0J 1Y0 Prepared by: Ocean Ecology Cover photo: Brian Huntington Ocean Ecology Skeena River Estuary Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................. ii List of Figures .................................................................................................................................. iii List of Tables ................................................................................................................................... iv Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... vi 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Chatham Sound ................................................................................................................ 7 1.2 Skeena River Estuary ..................................................................................................... 10 1.3 Environmental Concerns ................................................................................................ -

Ecosystem Status and Trends Report for North Coast and Hecate Strait Ecozone

C S A S S C C S Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Secrétariat canadien de consultation scientifique Research Document 2010/045 Document de recherche 2010/045 Ecosystem Status and Trends Report Rapport de l’état des écosystèmes et for North Coast and Hecate Strait des tendances pour l'écozone de la côte ecozone nord et du détroit de Hécate Patrick Cummins1 and Rowan Haigh2 1 Fisheries and Oceans Canada / Pêches et Océans Canada Institute of Ocean Sciences / Institut des sciences de la mer P.O. Box 6000 / C. P. 6000 Sidney, C.-B. V8L 4B2 2 Fisheries and Oceans Canada / Pêches et Océans Canada Pacific Biological Station/Station biologique du Pacifique 3190 Hammond Bay Road, Nanaimo, C.-B. V9T 6N7 This series documents the scientific basis for the La présente série documente les fondements evaluation of aquatic resources and ecosystems scientifiques des évaluations des ressources et in Canada. As such, it addresses the issues of des écosystèmes aquatiques du Canada. Elle the day in the time frames required and the traite des problèmes courants selon les documents it contains are not intended as échéanciers dictés. Les documents qu’elle definitive statements on the subjects addressed contient ne doivent pas être considérés comme but rather as progress reports on ongoing des énoncés définitifs sur les sujets traités, mais investigations. plutôt comme des rapports d’étape sur les études en cours. Research documents are produced in the official Les documents de recherche sont publiés dans language in which they are provided to the la langue officielle utilisée dans le manuscrit Secretariat. envoyé au Secrétariat. -

In This Issue

THE ZONE Welcome to the Spring 2018 issue of THE ZONE, the CZCA digital newsletter. Coastal Zone Canada 2018 Conference • St. John’s, NL Keith Mercer, Planning Chair: CZC’18 You’re all invited to come to St. John’s, NL, to attend CZC’18, from July 15th-19th. The conference will be held on the Sunday evening marks the opening of the Commentary: campus of Memorial University of Newfoundland and at main conference, with the keynote address 3 Canada’s Oceans other venues in the city. The conference theme is “Seeking by environmental, cultural and human rights Act at 20; A Pacific Practical Solutions to Real Issues: Communities Adapting to advocate, Sheila Watt-Cloutier. In 2007, Watt- Canada Perspective a Changing World”. I’m very proud to say that our planning Cloutier was nominated for the Nobel Peace committee has been working hard to make this event both Prize for her advocacy work in showing the A Scan of the Eastern exciting and informative. Our program is filled with fantastic impact of global climate change on human 9 Canadian Coastal special sessions, concurrent sessions, poster sessions, social rights, especially in the Arctic. This event will Region events, and more! be open to the public, and we expect a big turnout! Coastal Defence We kick off the conference with our Future Leaders Forum, 12 Roles of Mangroves on Sunday, July 15th, at the Delta Hotel Ballroom, in historic From Monday to Wednesday, special sessions on the Amazon- downtown St. John’s. The event is designed to help young and concurrent sessions will focus on the three In this issue Influenced Coast of Guyana, South professionals with networking, employment direction, sub-themes of the conference: Change and America: Review and gaining insight into the future of integrated ocean and Challenge – Realizing Opportunity, Engagement of an Intervention coastal management. -

Common (Left) and Yellow-Billed (Right) Loons at Nanoose Bay, BC. a Record Total of 17 Yellow- Billed Loons Were Seen on BC

British Columbia – Yukon 104th Christmas Bird Count: 14 December 2003—5 January 2004 Richard J. Cannings A record total of 80 counts came in from the British Columbia-Yukon region this year, with new counts from Apex-Hedley, Carcross, Cawston, Little River-Powell River Ferry, Logan Lake, Lower Howe Sound, Tlell and Vanderhoof, while the Hecate Strait ferry route survey was revived after many years. It is especially good to see the latter count back—it covers a part of the coast well known for remarkable concentrations of waterfowl and seabirds. December was on the mild side, but counts done in early January--especially those in the Yukon and the northern half of British Columbia--had to deal with very wintry low temperatures. Fort St. James had a low of -31ºF while Dawson Creek experienced -29º with winds of up to 20 mph. The species count in British Columbia bounced back to 225 (218 last year) and Yukon’s species count did the same (34 vs. 21 last year). Ladner retained the species total crown with 140 species, and Oliver-Osoyoos led the way again in the Interior with 107. In the Yukon, Whitehorse was alone in the lead with 22 species. Yellow-billed Loons surpassed even last year’s high totals, with 17 reported on 9 counts. Six were seen from the Hecate Strait ferry, but the rest were on the east coast of Vancouver Island, including 3 at Nanaimo and 2 at Nanoose Bay. Clark’s Grebes are unusual anywhere in British Columbia, so two at Lardeau were doubly unexpected. -

Pdf/17/2/375/5259835/375.Pdf 375 by Guest on 02 October 2021 Research Paper

Research Paper THEMED ISSUE: Tectonic, Sedimentary, Volcanic, and Fluid Flow Processes along the Queen Charlotte–Fairweather Fault System and Surrounding Continental Margin GEOSPHERE Late Quaternary sea level, isostatic response, and sediment GEOSPHERE, v. 17, no. 2 dispersal along the Queen Charlotte fault 1 2,3 1 4 https://doi.org/10.1130/GES02311.1 J. Vaughn Barrie , H. Gary Greene , Kim W. Conway , and Daniel S. Brothers 1Geological Survey of Canada–Pacific, Institute of Ocean Sciences, P.O. Box 6000, Sidney, British Columbia V8L 4B2, Canada 2SeaDoc Tombolo Mapping Laboratory, Orcas Island, Eastsound, Washington 98245, USA 9 figures; 1 table 3Center for Habitat Studies, Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, Moss Landing, California 95039, USA 4Pacific Coastal and Marine Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, Santa Cruz, California 95060, USA CORRESPONDENCE: [email protected] ABSTRACT Alexander Archipelago are exposed to an extreme wave regime (Thomson, CITATION: Barrie, J.V., Greene, H.G., Conway, K.W., and Brothers, D. S., 2021, Late Quaternary sea level, 1981, 1989). In addition to being an exposed high-wave-energy environment, isostatic response, and sediment dispersal along the The active Pacific margin of the Haida Gwaii and southeast Alaska has the area has also undergone dramatic sea-level fluctuations and is the most Queen Charlotte fault: Geosphere, v. 17, no. 2, p. 375– been subject to vigorous storm activity, dramatic sea-level change, and active seismically active area in Canada. With limited access and the energetic shore- 388, https://doi.org/10.1130/GES02311.1. tectonism since glacial times. Glaciation was minimal along the western shelf line, these shores have been, and are, relatively uninhabited, and some marine margin, except for large ice streams that formed glacial valleys to the shelf areas are not yet charted. -

Marine Distribution, Abundance, and Habitats of Marbled Murrelets in British Columbia

Chapter 29 Marine Distribution, Abundance, and Habitats of Marbled Murrelets in British Columbia Alan E. Burger1 Abstract: About 45,000-50,000 Marbled Murrelets (Brachyramphus birds) are extrapolations from relatively few data from 1972 marmoratus) breed in British Columbia, with some birds found in to 1982, mainly counts in high-density areas and transects most parts of the inshore coastline. A review of at-sea surveys at covering a small portion of coastline (Rodway and others 84 sites revealed major concentrations in summer in six areas. 1992). Between 1985 and 1993 many parts of the British Murrelets tend to leave these breeding areas in winter. Many Columbia coast were censused, usually by shoreline transects, murrelets overwinter in the Strait of Georgia and Puget Sound, but the wintering distribution is poorly known. Aggregations in sum- although methods and dates varied, making comparisons mer were associated with nearshore waters (<1 km from shore in and extrapolation difficult. Much of the 27,000 km of coastline exposed sites, but <3 km in sheltered waters), and tidal rapids and remains uncensused (fig. 1). narrows. Murrelets avoided deep fjord water. Several surveys showed Appendix 1 summarizes censuses for the core of the considerable daily and seasonal variation in densities, sometimes breeding season (1 May through 31 July). Murrelet densities linked with variable prey availability or local water temperatures. are given as birds per linear kilometer of transect. It was Anecdotal evidence suggests significant population declines in the necessary to convert density estimates from other units in Strait of Georgia, associated with heavy onshore logging in the several cases, and this was done in consultation with the early 1900s. -

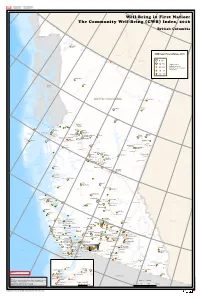

The Community Well-Being (CWB) Index, 2016

141° W 138° W 135° W 132° W 129° W 126° W 123° W Well-Being in First Nation: The Community Well-Being (CWB) Index, 2016 British Columbia Tagish Lake N ° 3 Atlin 6 ! Five Mile ·! Point 3 Atlin Lake Teslin Lake N ° 7 5 CWB Index Score Range, 2016 YUKON ¸ 0 - 49 Lower Post ·! ¸ 50 - 59 Higher scores TERRITOIRES iDnUdi cNaOteR Da -gOrUeaEtSeTr ! NORTHWEST TERRITORIES · 60 - 69 level of socio-economic well-being. ^^ 70 - 79 ^^ 80 - 100 Liard River Guhthe Tah 12 ! L ·! ia ! r d r e R iv iv e R r e in k ti S Iskut 6 Alaska ! (U.S.) !· F or t N els on R iv er N ° 0 6 Fort Nelson 2 BRITISH COLUMBIA Fort Nelson !!P·! Kotcho Lake Fo¸ rt Ware 1 Prophet River 4 ! !·! ! Stewart N ° 4 5 Ingenika !Po¸ int Gitanmaax 1 Nisga'a Hagwilget 1 ! ! ! Masset 1 !· !! Lax !·!! Gitanyo¸ w 1 ! ¸ Kispiox 1 Masset !Kw'alaams 1 ¸ ¸ ! ! !¸ !·Sik-e-dakh 2 S1/2 Tsimpsean 2 !! ¸ !! !·!·! Hazelton !" Prince Gitwangak 1! ! North Blueberry Coryatsaqua ¸ Halfway ¸ ! Babine 6 ¸ River 205 Tacla Lake Williston lake Gitsegukla 1 ¸ Rupert (M¸ oricetown) 2 River 168 ¸ ! ! ! Queen Kitsumkaylum 1 Terrace Babine 17 ·! Charlotte !Bulkley River 19 Dolphin !·!" ·! Moricetown 1 City Skidegate 1 ¸ ! ! Island 1 !·! Kitselas 1 Doig River 206 !^ Kulspai 6 Takla !·! ^!! ! !P Lake Sandspit Smithers Peace ! Fort Ba¸ bine 25 Hudson's Hope " Kitimat West Moberly !P Lake 168A St. John R iv Babine e N Kitamaat 2 East Moberly r ·! ° ! Lake ·!! 7 Trembleur !!·! Lake 169 5 Houston!P Lake Mackenzie !P Morice Chetwynd Lake ¸ ! Ye Koo Che 3 Ta¸ che 1 ! " !W¸ oyenne 27 ! ! Binche 2 McLeod Lake 1 Dawson !!!P ·! (Pinchie 2) ^! Creek Francois Burns Lake ! ^ Lake Stuart Nak'azdli Carp Lake Lake !Ch¸ eslatta 1 !!P (Necoslie 1) !! Fort St. -

Sockeye Salmon (Oncorhynchus Nerka)

Sockeye Salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) Supporting documentation and summary for Red List assessments at species and subpopulation levels The Salmonid Specialist Group (SSG) of the Species Survival Commission of IUCN World Conservation Union has been focusing on range-wide status assessments of salmonids. This assessment is an update of the first effort to add an anadromous (that is, sea-run) Pacific salmon to the IUCN Red List of Threatened SpeciesTM. We considered extinct and extant populations throughout the native range of the species, including the United States of America (States of Washington, Idaho, Oregon and Alaska), Canada (Province of British Columbia, Yukon Territory) and the Russia Federation (Kamchatka, Koryakia, Magadan, Chukotka). We assembled data on range and adult abundance (over 12 years, representing three generations) for Sockeye Salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) from 300 separate spawning sites across the Pacific Rim. Using this database and some additional information, we evaluated the status of anadromous Sockeye Salmon at both global and subpopulation scales according to IUCN Red List criteria version 3.1. We provide Red List Categories for Sockeye Salmon at both the global population level and for a total of 98 subpopulations defined by freshwater and marine ecoregional groupings and genetic differentiation. The subpopulations, as a result of guidelines stipulated by IUCN, represent coarse units defined by extremely low rates of geneflow (less than or equal to one effective migrant exchanged per year) and, as a result, may contain numerous spawning sites supporting sockeye salmon adapted to specific nursery lakes or river reaches. For our global population assessment, we concluded that the species as a whole is not threatened and, thus, assess its current status as Least Concern. -

West Ouest 07 18 En.Docx

NOTICES TO MARINERS PUBLICATION WESTERN EDITION MONTHLY EDITION Nº07 July 27th, 2018 Safety First, Service Always Published Monthly by the CANADIAN COAST GUARD www.notmar.gc.ca/subscribe CONTENTS Page Section 1 General and Safety Information ...................................................................................................... 1 - 7 Section 2 Chart Corrections ............................................................................................................................ 8 - 12 Section 3 Radio Aids to Marine Navigation Corrections ................................................................................ N/A Section 4 Sailing Directions and Small Craft Guide Corrections.................................................................... 14 - 16 Section 5 List of Lights, Buoys and Fog Signals Corrections ......................................................................... 17 Fisheries and Oceans Canada Official Publication of the Canadian Coast Guard DFO/2018-2003 Notices to Mariners Publication Western Edition Monthly Edition Nº07/2018 Published under the authority of: Canadian Coast Guard Programs Aids to Navigation and Waterways Fisheries and Oceans Canada Montreal, Quebec H2Y 2E7 © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2018 DFO/2018-2003 Fs152-6E-PDF ISSN 1719-7708 Available on the Notices to Mariners website: www.notmar.gc.ca Disponible en français : Publication des Avis aux navigateurs Édition de l’Ouest Édition mensuelle Nº07/2018 Fisheries and Oceans Canada Official Publication of the