Willingness Toupee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak. by Rose Ann Ko2inski Thesis presented as a partial requirement in the Master of Arts (M.A.) in Human Development School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Rose Ann Kozinski, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Die Flexible Welt Der Simpsons

BACHELORARBEIT Herr Benjamin Lehmann Die flexible Welt der Simpsons 2012 Fakultät: Medien BACHELORARBEIT Die flexible Welt der Simpsons Autor: Herr Benjamin Lehmann Studiengang: Film und Fernsehen Seminargruppe: FF08w2-B Erstprüfer: Professor Peter Gottschalk Zweitprüfer: Christian Maintz (M.A.) Einreichung: Mittweida, 06.01.2012 Faculty of Media BACHELOR THESIS The flexible world of the Simpsons author: Mr. Benjamin Lehmann course of studies: Film und Fernsehen seminar group: FF08w2-B first examiner: Professor Peter Gottschalk second examiner: Christian Maintz (M.A.) submission: Mittweida, 6th January 2012 Bibliografische Angaben Lehmann, Benjamin: Die flexible Welt der Simpsons The flexible world of the Simpsons 103 Seiten, Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Bachelorarbeit, 2012 Abstract Die Simpsons sorgen seit mehr als 20 Jahren für subversive Unterhaltung im Zeichentrickformat. Die Serie verbindet realistische Themen mit dem abnormen Witz von Cartoons. Diese Flexibilität ist ein bestimmendes Element in Springfield und erstreckt sich über verschiedene Bereiche der Serie. Die flexible Welt der Simpsons wird in dieser Arbeit unter Berücksichtigung der Auswirkungen auf den Wiedersehenswert der Serie untersucht. 5 Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis ............................................................................................. 5 Abkürzungsverzeichnis .................................................................................... 7 1 Einleitung ................................................................................................... -

Social Condition of England During the Wars of the Roses Author(S): Vincent B

Social Condition of England during the Wars of the Roses Author(s): Vincent B. Redstone Source: Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, New Series, Vol. 16 (1902), pp. 159-200 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Royal Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3678121 Accessed: 27-06-2016 09:27 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Royal Historical Society, Cambridge University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Transactions of the Royal Historical Society This content downloaded from 198.91.37.2 on Mon, 27 Jun 2016 09:27:49 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms SOCIAL CONDITION OF ENGL ANI) DURING THE WARS OF THE ROSES. BY VINCENT B. REDSTONE Read Marsk 20, I902. THE social life of the inhabitants of England during the Introduc years of strife which brought about the destruction of the t on- feudal nobility, gave to the middle class a new position in the State, and freed the serf from the shackles of bondage, has been for some time past a subject of peculiar interest to the student of English history. -

Beauty Trends 2015

Beauty Trends 2015 HAIR CARE EDITION (U.S.) The image The image cannot be cannot be displayed. displayed. Your Your computer computer may not have may not have enough enough memory to memory to Intro open the open the With every query typed into a search bar, we are given a glimpse into user considerations or intentions. By compiling top searches, we are able to render a strong representation of the United States’ population and gain insight into this specific population’s behavior. In our Google Beauty Trends report, we are excited to bring forth the power of big data into the hands of the marketers, product developers, stylists, trendsetters and tastemakers. The goal of this report is to share useful data for planning purposes accompanied by curated styles of what we believe can make for impactful trends. We are proud to share this iteration and look forward to hearing back from you. Flynn Matthews | Principal Industry Analyst, Beauty Olivier Zimmer | Trends Data Scientist Yarden Horwitz | Trends Brand Strategist Photo Credit: Blind Barber (Men’s Hair), Meladee Shea Gammelseter (Women’s Hair), Andrea Grabher/Christian Anwander (Colored Hair), Catface Hair (Box & Twist Braids), Maria Valentino/MCV photo (Goddess Braid) Proprietary + Confidential Methodology QUERY To compile a list of accurate trends within the Jan-13 Aug-13 Jan-14 Aug-14 Jan-15 Aug-15 beauty industry, we pulled top volume queries related to the beauty category and looked at their monthly volume from January 2013 to August 2015. We first removed any seasonal effect, and DE-SEASONALIZED QUERY then measured the year-over-year growth, velocity, and acceleration for each search query. -

Getting to the Root of Hair Loss

26 March 2012 | MP3 at voaspecialenglish.com Getting to the Root of Hair Loss Reuters An example of male pattern baldness SHIRLEY GRIFFITH: This is SCIENCE IN THE NEWS in VOA Special English. I'm Shirley Griffith. JUNE SIMMS: And I'm June Simms. Today we talk about hair. We will tell what hair is, how it grows, and some of the main reasons people lose it. (MUSIC) SHIRLEY GRIFFITH: Hair has always been an important sign of beauty. This is especially true for women. Next to the face, hair is one of the main qualities people look for when they consider a woman's beauty. Whether long or short, curly or straight, hair often gets a lot of attention. People who have it value it. Those of us who do not often mourn its loss. JUNE SIMMS: Each hair on a person's head grows from a single tube-like hole in the skin called a follicle. People are born with all of the hair follicles they are ever going to have. The average person has about one hundred thousand hair follicles. They begin to form on a fetus around the third month of pregnancy. 2 The part of the hair under the skin is known as the hair root. The hair sticking out from the skin is known as the hair shaft. The shaft is made up of dead cells that have been pushed up through the root. At the base of the hair root is a small ball-like formation called a bulb. This is where new cells are formed. -

Ll||L||||||||L||||||||L|||||||||||||||||||||||L||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| US 20060005394A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub

l|||||||||||||ll||l||||||||l||||||||l|||||||||||||||||||||||l||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| US 20060005394A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0005394 A1 Newkirk et al. (43) Pub. Date: Jan. 12, 2006 (54) RAZOR FOR BUZZ CUTTING HEAD HAIR Publication Classi?cation (76) Inventors: James C. Newkirk, Crescent Springs, (51) Int. Cl. KY (US); Donna M. Newkirk, B26B 21/00 (2006.01) Crescent Springs, KY (US) (52) US. Cl. ................................................................ .. 30/50 Correspondence Address: WOOD, HERRON & EVANS, LLP (57) ABSTRACT 2700 CAREW TOWER 441 VINE STREET CINCINNATI, OH 45202 (Us) A dual Wet razor device is used for shaving hair on a head at different lengths. The device has a ?rst and a second (21) Appl. No.: 10/886,090 cutting edge on opposite sides of one another and a sensitive guide under each cutting edge for safely cutting different 22 Filed: Jul. 7, 2004 short len g ths of hair on the sealP of a user. \\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\W\X,\ // J ///// Patent Application Publication Jan. 12, 2006 Sheet 1 0f 2 US 2006/0005394 A1 \\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\F US 2006/0005394 A1 Jan. 12, 2006 RAZOR FOR BUZZ CUTTING HEAD HAIR distance. In a preferred form, the sensitive guide is formed by a plurality of rounded knobs Which cooperate With the FIELD OF THE INVENTION cutting blade so as to provide a smooth, clean and safe haircut. Thus, the dual raZor avoids cutting abnormalities on [0001] This invention relates to a head shaving razor and, the scalp, such as moles, scars or folds in the skin, and the in particular, to a raZor designed for Wet shaving of hair like. -

The Evolution of the Seven Deadly Sins: from God to the Simpsons

96 Journal of Popular Culture sin. A lot. As early Christian doctrine repeatedly points out, the seven deadly sins are so deeply rooted in our fallen human nature, that not only are they almost completely unavoidable, but like a proverbial bag of The Evolution of the Seven Deadly Sins: potato chips, we can never seem to limit ourselves to just one. With this ideology, modern society agrees. However, with regard to the individual From God to the Simpsons and social effects of the consequences of these sins, we do not. The deadly sins of seven were identified, revised, and revised again Lisa Frank in the heads and classrooms of reportedly celibate monks as moral and philosophical lessons taught in an effort to arm men and women against I can personally attest that the seven deadly sins are still very much the temptations of sin and vice in the battle for their souls. These teach- with us. Today, I have committed each of them, several more than once, ings were quickly reflected in the literature, theater, art, and music of before my lunch hour even began. Here is my schedule of sin (judge me that time and throughout the centuries to follow. Today, they remain pop- if you will): ular motifs in those media, as well as having made the natural progres- sion into film and television. Every day and every hour, acts of gluttony, 7:00 - I pressed the snooze button three times before dragging myself out of lust, covetousness, envy, pride, wrath, and sloth are portrayed on televi- bed. -

Movember in Molumbus Stickme: Acupuncture H

THe aLTernanve HeaLTOTssue insiDe: sociaLTsar ROBBie STePHens are YOU a STress mess? MOvemBer in moLumBus STICK me: acupuncTure HanDS on HeannG MaDLaB APOcaLYPse siLver Moon RisinG A LITTLe DOG I.aUGHeD inTerview: miKa OUT & PFOUD o ll74470"25134 ' 7 & LOCaL CeLeBIITY BLOGGerS by Erin McCalla 2010, the shop has been enthusiastically re ceived and increasingly successful. Greg's When I enter the Blue Star Barbershop, goal was to do 100 cuts a day, and Blue Star Johnny Cash is pumping through the speak has beaten that number... handily. ers. He's singing about shooting a man in Reno, just to watch him die and subsequently He explains that it's his superb staff that ending up in Folsom Prison. Johnny Cash keeps the clients coming back. Greg has his wouldn't get his haircut in a beauty salon, and employees go through a stringent screening if you're a man (or a lesbian with a short 'do), process before they even sharpen their neither should you. shears. This isn't your bargain bin buzz cut as each potential hire goes through three in That's because this locally (and queer) owned terviews and a technical try out that's why barbershop employs people who are really you can't get a better cut in town for the focused and adept at giving great haircuts, price. ($19!) tapers and fades to "smart men who want to look sharp." He's not knocking his swanky salon sisters and brothers, but Greg is passionate when it And speaking of sharp looking men, Greg comes to a man's mop and suggests that men Hund, the suave and sawy proprietor of Blue should stay away from salons with women- Star, opened this 9-chair shop two years ago based clienteles. -

GRI, School of Economics & Commercial Law at Gˆteborg

= = = = = = = = dofJê~ééçêí=OMMQWQ= = píêçåÖ=mäçíëW= qÜÉ=oÉä~íáçåëÜáé=_ÉíïÉÉå=mçéìä~ê=`ìäíìêÉ=~åÇ=j~å~ÖÉãÉåí=mê~ÅíáÅÉ=C=qÜÉçêó= = _~êÄ~ê~=`ò~êåá~ïëâ~=~åÇ=`~êä=oÜçÇÉë= = = = = = = = = = = = dofI=pÅÜççä=çÑ=bÅçåçãáÅë=C=`çããÉêÅá~ä=i~ï=~í=d∏íÉÄçêÖ=råáîÉêëáíóI=pïÉÇÉå= ~åÇ=c~Åìäíó=çÑ=bÇìÅ~íáçåI=råáîÉêëáíó=çÑ=qÉÅÜåçäçÖóI=póÇåÉóI=^ìëíê~äá~= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = cçêíÜÅçãáåÖ=áå=m~ëèì~äÉ=d~Öäá~êÇá=~åÇ=_~êÄ~ê~=`ò~êåá~ïëâ~=EÉÇëKF=Management & Humanities. -

2011 06 Kamus Saku Tado 1A

Nama angka : 1 saungu satu one 2 roungu dua two 3 toluongu tiga three 4 aopo empat four 5 alima lima five 6 aono enam six 7 papitu tujuh seven 8 uwalu delapan eight 9 sasio sembilan nine 10 sampulu sepuluh ten 11 sampulu saungu sebelas eleven 12 sampulu roungu duabelas twelve 13 sampulu toluongu tigabelas thirteen 14 sampulu aopo empat belas fourteen 15 sampulu alima lima belas fifteen 16 sampulu aono enam belas sixteen 17 sampulu papitu tujuh belas seventeen 18 sampulu uwalu delapan belas eighteen 19 sampulu sasio sembilan belas nineteen 20 rompulu dua puluh twenty 30 tolu mpulu tiga puluh thirty 40 aopo mpulu empat puluh forty 50 lima mpulu lima puluh fifty 60 aono mpulu enam puluh sixty 70 pitu mpulu tujuh puluh seventy 80 walu mpulu delapan puluh eighty 90 sio mpulu sembilan puluh ninety 100 saatu seratus one hundred 200 roatu dua ratus two hundred 300 toluatu tiga ratus three hundred 400 opoatu empat ratus four hundred 500 limatu lima ratus five hundred 600 aonoatu enam ratus six hundred 700 pituatu tujuh ratus seven hundred 800 waluatu delapan ratus eight hundred 900 sioatu sembilan ratus nine hundred 1000 sanjobu seribu one thousand Nama hari : eo Minggu hari Minggu Sunday eo Sinei hari Senin Monday eo Salasa hari Selasa Tuesday eo Rabu hari Rabu Wednesday eo Kamisi hari Kamis Thursday eo Jumaa hari Jum'at Friday eo Satu hari Sabtu Saturday Nama bulan : Wula Saungu Januari January Wula Roungu Februari February Wula Tuluongu Maret March Wula Aopongu April April Wula Limaongu Mei May Wula Aonongu Juni June Wula Pituongu Juli July Wula Waluongu Agustus August Wula Siongu September September Wula Sampuluongu Oktober October Wula Sampulu Saungu November November Wula Sampulu Roungu Desember December KAMUS SAKU BAHASA TADO-LINDU — INDONESIA — INGGRIS Disusun oleh Tim Kerja Pengembangan Bahasa Tado-Lindu: Bance Tarua Erik Pengei, S.Pd. -

Surnames in Bureau of Catholic Indian

RAYNOR MEMORIAL LIBRARIES Montana (MT): Boxes 13-19 (4,928 entries from 11 of 11 schools) New Mexico (NM): Boxes 19-22 (1,603 entries from 6 of 8 schools) North Dakota (ND): Boxes 22-23 (521 entries from 4 of 4 schools) Oklahoma (OK): Boxes 23-26 (3,061 entries from 19 of 20 schools) Oregon (OR): Box 26 (90 entries from 2 of - schools) South Dakota (SD): Boxes 26-29 (2,917 entries from Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions Records 4 of 4 schools) Series 2-1 School Records Washington (WA): Boxes 30-31 (1,251 entries from 5 of - schools) SURNAME MASTER INDEX Wisconsin (WI): Boxes 31-37 (2,365 entries from 8 Over 25,000 surname entries from the BCIM series 2-1 school of 8 schools) attendance records in 15 states, 1890s-1970s Wyoming (WY): Boxes 37-38 (361 entries from 1 of Last updated April 1, 2015 1 school) INTRODUCTION|A|B|C|D|E|F|G|H|I|J|K|L|M|N|O|P|Q|R|S|T|U| Tribes/ Ethnic Groups V|W|X|Y|Z Library of Congress subject headings supplemented by terms from Ethnologue (an online global language database) plus “Unidentified” and “Non-Native.” INTRODUCTION This alphabetized list of surnames includes all Achomawi (5 entries); used for = Pitt River; related spelling vartiations, the tribes/ethnicities noted, the states broad term also used = California where the schools were located, and box numbers of the Acoma (16 entries); related broad term also used = original records. Each entry provides a distinct surname Pueblo variation with one associated tribe/ethnicity, state, and box Apache (464 entries) number, which is repeated as needed for surname Arapaho (281 entries); used for = Arapahoe combinations with multiple spelling variations, ethnic Arikara (18 entries) associations and/or box numbers. -

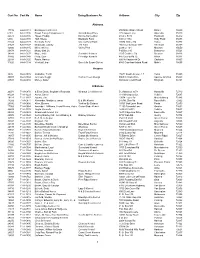

Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip 1 Cust No

Cust No Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip Alabama 17732 64-A-0118 Barking Acres Kennel 250 Naftel Ramer Road Ramer 36069 6181 64-A-0136 Brown Family Enterprises Llc Grandbabies Place 125 Aspen Lane Odenville 35120 22373 64-A-0146 Hayes, Freddy Kanine Konnection 6160 C R 19 Piedmont 36272 6394 64-A-0138 Huff, Shelia Blackjack Farm 630 Cr 1754 Holly Pond 35083 22343 64-A-0128 Kennedy, Terry Creeks Bend Farm 29874 Mckee Rd Toney 35773 21527 64-A-0127 Mcdonald, Johnny J M Farm 166 County Road 1073 Vinemont 35179 42800 64-A-0145 Miller, Shirley Valley Pets 2338 Cr 164 Moulton 35650 20878 64-A-0121 Mossy Oak Llc P O Box 310 Bessemer 35021 34248 64-A-0137 Moye, Anita Sunshine Kennels 1515 Crabtree Rd Brewton 36426 37802 64-A-0140 Portz, Stan Pineridge Kennels 445 County Rd 72 Ariton 36311 22398 64-A-0125 Rawls, Harvey 600 Hollingsworth Dr Gadsden 35905 31826 64-A-0134 Verstuyft, Inge Sweet As Sugar Gliders 4580 Copeland Island Road Mobile 36695 Arizona 3826 86-A-0076 Al-Saihati, Terrill 15672 South Avenue 1 E Yuma 85365 36807 86-A-0082 Johnson, Peggi Cactus Creek Design 5065 N. Main Drive Apache Junction 85220 23591 86-A-0080 Morley, Arden 860 Quail Crest Road Kingman 86401 Arkansas 20074 71-A-0870 & Ellen Davis, Stephanie Reynolds Wharton Creek Kennel 512 Madison 3373 Huntsville 72740 43224 71-A-1229 Aaron, Cheryl 118 Windspeak Ln. Yellville 72687 19128 71-A-1187 Adams, Jim 13034 Laure Rd Mountainburg 72946 14282 71-A-0871 Alexander, Marilyn & James B & M's Kennel 245 Mt.