Farmland Birds and Agri-Environment Schemes in the New Member States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Olume 39 • No 5 • 2017

DUTCH BIRDINGVOLUME 39 • NO 5 • 2017 Dutch Birding Dutch Birding HOO F D R EDACTEU R Arnoud van den Berg (06-54270796, [email protected]) ADJUNCT HOO F D R EDACTEU R Enno Ebels (030-2961335, [email protected]) UITVOE R END R EDACTEU R André van Loon (020-6997585, [email protected]) FOTOG R A F ISCH R EDACTEU R René Pop (06-22396323, [email protected]) REDACTIE R AAD Peter Adriaens, Sander Bot, Thijs Fijen, Dick Groenendijk, Łukasz Ławicki, Gert Ottens, Roy Slaterus, Roland van der Vliet en Peter de Vries REDACTIE -ADVIES R AAD Peter Barthel, Mark Constantine, Andrea Corso, Dick Forsman, Ricard Gutiérrez, Killian Mullarney, Klaus Malling Olsen, Magnus Robb, Hadoram Shirihai en Lars Svensson REDACTIEMEDEWE R KE R S Garry Bakker, Mark Collier, Harvey van Diek, Nils van Duivendijk, Willem-Jan Internationaal tijdschrift over Fontijn, Hans Groot, Justin Jansen, Jan van der Laan, Hans van der Meulen, Mark Nieuwenhuis, Palearctische vogels Jelmer Poelstra, Martijn Renders, Kees Roselaar, Vincent van der Spek en Jan Hein van Steenis LAY -OUT André van Loon PR ODUCTIE André van Loon en René Pop REDACTIE Dutch Birding ADVE R TENTIES Debby Doodeman, p/a Dutch Birding, Postbus 75611, 1070 AP Amsterdam Duinlustparkweg 98A [email protected] 2082 EG Santpoort-Zuid ABONNEMENTEN De abonnementsprijs voor 2017 bedraagt: EUR 40.00 (Nederland), EUR 42.50 Nederland (België), EUR 43.50 (rest van Europa) en EUR 45.00 (landen buiten Europa). [email protected] U kunt zich abonneren door het overmaken van de abonnementsprijs op bankrekening (IBAN): NL95 INGB 0000 1506 97; BIC: INGBNL2A ten name van Dutch Birding Association te Amsterdam, FOTO R EDACTIE ovv ‘abonnement Dutch Birding’ en uw postadres. -

Derogation Reporting for 2007

Report on derogations in 2007, Birds Directive 79/409/EEC Article 9 COMPOSITE EUROPEAN COMMISSION REPORT ON DEROGATIONS IN 2007 ACCORDING TO ARTICLE 9 OF DIRECTIVE 79/409/EEC ON THE CONSERVATION OF WILD BIRDS DECEMBER 2009 1 Report on derogations in 2007, Birds Directive 79/409/EEC Article 9 CONTENTS Introduction........................................................................................................... 3 1 Methodology................................................................................................. 4 2 Overview of derogations across the EU........................................................ 7 3 Member State reports.................................................................................. 12 3.1 Austria................................................................................................. 12 3.2 Belgium............................................................................................... 14 3.3 Bulgaria............................................................................................... 15 3.4 Cyprus................................................................................................. 16 3.5 Czech Republic................................................................................... 17 3.6 Denmark.............................................................................................. 18 3.7 Estonia................................................................................................. 19 3.8 Finland ............................................................................................... -

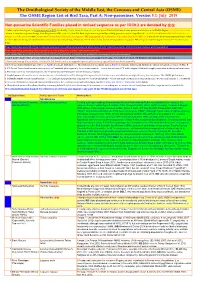

ORL 5.1 Non-Passerines Final Draft01a.Xlsx

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part A: Non-passerines. Version 5.1: July 2019 Non-passerine Scientific Families placed in revised sequence as per IOC9.2 are denoted by ֍֍ A fuller explanation is given in Explanation of the ORL, but briefly, Bright green shading of a row (eg Syrian Ostrich) indicates former presence of a taxon in the OSME Region. Light gold shading in column A indicates sequence change from the previous ORL issue. For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates added information since the previous ORL version or the Conservation Threat Status (Critically Endangered = CE, Endangered = E, Vulnerable = V and Data Deficient = DD only). Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative convenience and may change. Please do not cite them in any formal correspondence or papers. NB: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text indicate recent or data-driven major conservation concerns. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. English names shaded thus are taxa on BirdLife Tracking Database, http://seabirdtracking.org/mapper/index.php. Nos tracked are small. NB BirdLife still lump many seabird taxa. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. -

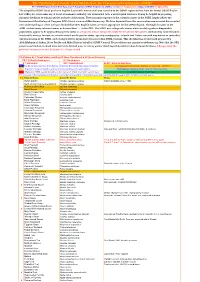

Simplified-ORL-2019-5.1-Final.Pdf

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part F: Simplified OSME Region List (SORL) version 5.1 August 2019. (Aligns with ORL 5.1 July 2019) The simplified OSME list of preferred English & scientific names of all taxa recorded in the OSME region derives from the formal OSME Region List (ORL); see www.osme.org. It is not a taxonomic authority, but is intended to be a useful quick reference. It may be helpful in preparing informal checklists or writing articles on birds of the region. The taxonomic sequence & the scientific names in the SORL largely follow the International Ornithological Congress (IOC) List at www.worldbirdnames.org. We have departed from this source when new research has revealed new understanding or when we have decided that other English names are more appropriate for the OSME Region. The English names in the SORL include many informal names as denoted thus '…' in the ORL. The SORL uses subspecific names where useful; eg where diagnosable populations appear to be approaching species status or are species whose subspecies might be elevated to full species (indicated by round brackets in scientific names); for now, we remain neutral on the precise status - species or subspecies - of such taxa. Future research may amend or contradict our presentation of the SORL; such changes will be incorporated in succeeding SORL versions. This checklist was devised and prepared by AbdulRahman al Sirhan, Steve Preddy and Mike Blair on behalf of OSME Council. Please address any queries to [email protected]. -

Notification to the Parties No. 2018/100

CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA NOTIFICATION TO THE PARTIES No. 2018/100 Geneva, 17 December 2018 CONCERNING: Standard nomenclature Standard references to be considered at CoP18 1. In Resolution Conf. 12.11 (Rev. CoP17) on Standard nomenclature, the Conference of the Parties RECOMMENDS, in paragraph 2 i), that: the Secretariat be provided with the citations (and ordering information) of checklists that will be nominated for standard references at least six months before the meeting of the Conference of the Parties at which such checklists will be considered. The Secretariat shall include such information in a Notification to the Parties so that Parties can obtain copies to review if they wish before the meeting. 2. In compliance with this recommendation, the nomenclature specialists for the Animals and Plants Committees have proposed the citations of checklists that will be nominated for taxonomic standard references at the 18th meeting of the Conference of the Parties (CoP18, Colombo, 2019). These are listed below, along with a link to where each reference can be accessed or ordered. FAUNA 3. The proposed standard references for fauna are as follows: Mammalia Kitchener A. C., Breitenmoser-Würsten CH., Eizirik E., Gentry A., Werdelin L., Wilting A., Yamaguchi N., Abramov A. V., Christiansen P., Driscoll C., Duckworth J. W., Johnson W., Luo S.-J., Meijaard E., O’Donoghue P., Sanderson J., Seymour K., Bruford M., Groves C., Hoffmann M., Nowell K., Timmons Z. and Tobe S. (2017). A revised taxonomy of the Felidae. The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. -

Supporting References for Nelson & Ellis

Supplemental Data for Nelson & Ellis (2018) The citations below were used to create Figures 1 & 2 in Nelson, G., & Ellis, S. (2018). The History and Impact of Digitization and Digital Data Mobilization on Biodiversity Research. Publication title by year, author (at least one ADBC funded author or not), and data portal used. This list includes papers that cite the ADBC program, iDigBio, TCNs/PENs, or any of the data portals that received ADBC funds at some point. Publications were coded as "referencing" ADBC if the authors did not use portal data or resources; it includes publications where data was deposited or archived in the portal as well as those that mention ADBC initiatives. Scroll to the bottom of the document for a key regarding authors (e.g., TCNs) and portals. Citation Year Author Portal used Portal or ADBC Program was referenced, but data from the portal not used Acevedo-Charry, O. A., & Coral-Jaramillo, B. (2017). Annotations on the 2017 Other Vertnet; distribution of Doliornis remseni (Cotingidae ) and Buthraupis macaulaylibrary wetmorei (Thraupidae ). Colombian Ornithology, 16, eNB04-1 http://asociacioncolombianadeornitologia.org/wp- content/uploads/2017/11/1412.pdf [Accessed 4 Apr. 2018] Adams, A. J., Pessier, A. P., & Briggs, C. J. (2017). Rapid extirpation of a 2017 Other VertNet North American frog coincides with an increase in fungal pathogen prevalence: Historical analysis and implications for reintroduction. Ecology and Evolution, 7, (23), 10216-10232. Adams, R. P. (2017). Multiple evidences of past evolution are hidden in 2017 Other SEINet nrDNA of Juniperus arizonica and J. coahuilensis populations in the trans-Pecos, Texas region. -

Initial Assessment of the Marine Environment of Cyprus Part I

REPUBLIC OF CYPRUS MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE, NATURAL RESOURCES, AND THE ENVIRONMENT DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES AND MARINE RESEARCH Initial Assessment of the Marine Environment of Cyprus Part I – Characteristics Nicosia, Cyprus July 2012 Implementation of Article 8 of the Marine Strategy Framework-Directive (2008/56/EC) Table of contents 1. Physical and chemical features ...................................................................................... 1 1.1 Topography and bathymetry of the seabed .............................................................. 1 1.1.1 Seafloor morphology .......................................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Bathymetry ........................................................................................................ 2 1.2 Annual and seasonal temperature regime and ice cover, current velocity, upwelling, wave exposure, mixing characteristics, turbidity, residence time ....................................... 4 1.2.1 Temperature ...................................................................................................... 4 1.2.1.1 Spatial distribution ....................................................................................... 4 1.2.1.2 Annual and seasonal evolution .................................................................... 7 1.2.1.3 Decadal and inter-decadal changes ............................................................. 8 1.2.2 Circulation and currents (including upwelling) ................................................... -

Reprising the Taxonomy of Cyprus Scops Owl Otus (Scops) Cyprius, a Neglected Island Endemic

Zootaxa 4040 (3): 301–316 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2015 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4040.3.3 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:2F5B4D53-4C9B-48AB-991E-8A090C03B360 Reprising the taxonomy of Cyprus Scops Owl Otus (scops) cyprius, a neglected island endemic PETER FLINT1, DAVID WHALEY2, GUY M. KIRWAN3, MELIS CHARALAMBIDES4, MANUEL SCHWEIZER5 & MICHAEL WINK6 114 Beechwood Avenue, Deal, Kent, CT14 9TD, UK. E-mail: [email protected] 2P.O. Box 8 Stroumbi, 8550 Paphos, Cyprus. E-mail: [email protected] 3Research Associate, Field Museum of Natural History, 1400 South Lakeshore Drive, Chicago, IL 60605, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 4P.O. Box 28076, 2090 Nicosia, Cyprus. E-mail: [email protected] 5Naturhistorisches Museum der Burgergemeinde Bern, Bernastrasse 15, CH 3005 Bern, Switzerland. E-mail: [email protected] 6Institut für Pharmazie und Molekulare Biotechnologie, Universität Heidelberg, Abt. Biologie, Im Neuenheimer Feld 364, D-69120 Heidelberg, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The endemic Cyprus Scops Owl Otus (scops) cyprius has been treated as a subspecies of the widespread Eurasian Scops Owl O. scops since at least the 1940s. However, its song is distinct from that of all other subspecies of O. scops in being double-noted, rather than single-noted. Its plumage also differs, most obviously in being consistently darker than other subspecies and in lacking a rufous morph. However, it shows no biometric differences from O. s. cycladum and southern populations of O. -

In the Marine Waters of Cyprus Second

ΚΥΠΡΙΑΚΗ ΔΗΜΟΚΡΑΤΙΑ ΥΠΟΥΡΓΕΙΟ ΓΕΩΡΓΙΑΣ, ΑΓΡΟΤΙΚΗΣ ΤΜΗΜΑ ΑΛΙΕΙΑΣ ΑΝΑΠΤΥΞΗΣ ΚΑΙ ΠΕΡΙΒΑΛΛΟΝΤΟΣ ΚΑΙ ΘΑΛΑΣΣΙΩΝΕΡΕΥΝΩΝ Update Of Articles 8, 9, And 10 Of The Marine Strategy Framework-Directive (2008/56/ΕC) In The Marine Waters Of Cyprus Second Assessment Report May 2019 Contents 1 Environmental features and characteristics ................................................... 3 1.1 Physical and chemical features ........................................................................... 3 1.1.1 Topography and bathymetry ........................................................................................... 3 1.1.2 Physical characteristics ................................................................................................... 4 1.1.3 Chemical characteristics ................................................................................................. 8 1.2 Habitat types ....................................................................................................... 11 1.2.1 Key features .................................................................................................................. 11 1.2.2 Special habitat types ..................................................................................................... 12 1.2.3 Habitats in areas which merit a particular reference ..................................................... 17 1.3 Biological features .............................................................................................. 20 1.3.1 Phytoplankton ............................................................................................................... -

Proposed New CITES Standard References for Nomenclature of Birds (Class Aves) Report of the Consultant November 14, 2018

CoP18 Doc. xx Annex 5 Proposed New CITES Standard References for Nomenclature of Birds (Class Aves) Report of the Consultant November 14, 2018 Ronald Orenstein Mississauga, Ontario, Canada L5L3W2 [email protected] Introduction Avian taxonomy has undergone a sea change since the publication of the 3rd edition of the Howard and Moore checklist of the birds of the world (Dickinson, 2003; hereafter H&M3). As the editors point out in the introduction (p. xi) to Volume 1 of the 4th edition of that checklist (Dickinson and Christidis (eds), 2013 (v. 1, Non-Passerines), 2014 (v. 2, Passerines); hereafter H&M4): “The explosion of research on the phylogeny of birds in the last decade, more than in any other in history, has led to dramatic changes in our understanding of the relationships among birds. This revolution means that the classification in H&M3 is not just badly out of date but in many places virtually obsolete. From relationships among orders of birds, to composition of families and genera, to many revelations of hidden species diversity, the classification of birds of the world has undergone major changes. This explosion has been ignited by the widespread use of techniques, particularly DNA sequencing, that allow direct assessment of the genetic signature of the phylogeny of birds.” These comments are even more relevant to the nomenclature of birds used in CITES, which still relies on a standard reference from 1975 for the names of orders and families and on another dating from 1997 for the treatment of some species of Psittaciformes. -

Sandgrousevolume 42(1) 2020

SandgrouseVOLUME 42(1) 2020 ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF THE MIDDLE EAST THE CAUCASUS AND CENTRAL ASIA ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF THE MIDDLE EAST THE CAUCASUS AND CENTRAL ASIA For details of OSME’s aims, membership, meetings, conservation and research funding, OSMEBirdNet, OSME recommended bird taxonomy, Sandgrouse instructions for authors and news and tweets see www.osme.org. VICE PRESIDENTS (AS AT FEBRUARY 2020): Dr Sergey Sklyarenko (Kazakhstan), Dr Ali Adhami Mirhosseyni (Iran), Dr Azzam Alwash (Iraq), Melis Charalambides (Cyprus), Dr Nabegh Ghazal Asswad (Syria). COUNCIL (AS AT FEBRUARY 2020): Michael Blair ([email protected], ORL Listmaster) Dr Robert Sheldon ([email protected], Paul Donald ([email protected], Chairman) Sandgrouse editor) AbdulRahman Al-Sirhan Tomas Haraldsson (youthdevelopment@ ([email protected], osme.org, Youth Development Officer) Website management–co-opted) Ian Harrison Paul Stancliffe Chris Hughes ([email protected], Effie Warr ([email protected], membership@ [email protected], Joint Treasurer & Advertising) osme.org, Sales & Membership–co-opted) Georgia Locock John Warr ([email protected], Nick Moran Joint Treasurer–co-opted). Sajidah Ahmad ([email protected], Secretary) CONSERVATION FUND COMMITTEE (AS AT FEBRUARY 2020): Dr Maxim Koshkin (Convener), Dr Nabegh Ghazal Asswad, Mick Green, Sharif Jbour, Richard Porter. OSME CORPORATE MEMBERS: Avifauna Nature Tours, Birdfinders, Birdtour Asia, Greentours, NHBS, Oriole Birding, Rockjumper Birding Tours, Sunbird. Sandgrouse: OSME’s peer-reviewed scientific journal publishes -

Overview of the Fauna in Cyprus

Fauna of Cyprus – an overview Seminar contribution to the module "Terrestrial Ecosystems" (2101-230) Institute of Botany (210a) · University of Hohenheim · Stuttgart presented by Ulrich Higl on January 21, 2019 Structure Arthropods Amphibians Reptiles Birds Mammals 09.02 Arthropods Cyprus is inhabited by approximately 6000 Insect-, 60 Spider- and 343 Crustacean- Species. [2] [3] Cyprian Cone-headed Grasshopper Truxalis European eximia cypria. Mantis Mantis religiosa. Endemic subspecies [4] [5] Globe-shaped Olive Scale „Trauer-Rosenkäfer“ Pollinia pollini. Oxythyrea funesta. 09.03 Lepidoptera There are 52 species of Butterflies in Cyprus, 3 of which are endemic [6] [7] [8] Cyprus Grayling Cyprus Meadow Brown Paphos Blue Hipparchia cypriensis Maniola cypricola Glaucopsyche paphos Found April-October in all of Found April-October in all of Found April-May in the Paphos Cyprus. Cyprus. Forest near Troodos. 09.04 Lepidoptera Pine Processionary Thaumetopoea pityocampa Moth of the family Thaumetopoeidae [9] [10] with a wingspan between 31 and 49mm. Adults only live one day in which they mate and lay their eggs. The caterpillars overwinter in tent- shaped silk nests. ♀ ♂ Adult female and male. The hairs of the caterpillars are highly [11] irritating and can cause severe rashes and eye irritation. The caterpillars will form long chains Procession of caterpillars. with up to 300 individuals to search for a pupation site. Silk nest. 09.05 Arachnids [12] Mesobuthus cyprius Endemic scorpion species described in 2000 with DNA-fingerprinting. Lives under medium sized rocks on sandy soils. [13] European Tarantula Lycosa tarantula Origin of the name Tarantula which today refers to members of the family Theraphosidae.