Critique of Nashville's Transit Improvement Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kapālama Canal Catalytic Project

KAPĀLAMA CANAL CATALYTIC PROJECT EXISTING CONDITIONS REPORT OCTOBER 2016 2 • EXISTING CONDITIONS REPORT - OCTOBER 2016 KAPĀLAMA CANAL CATALYTIC PROJECT Prepared by : with assistance from: KAPĀLAMA CANAL CATALYTIC PROJECT EXISTING CONDITIONS REPORT - OCTOBER 2016 • 3 Table of Contents 1 Introduction 1.1 Project Background and Location 4 2 Site Analysis 2.1 General Observations 6 2.2 Nimitz Highway to Dillingham Boulevard 10 2.3 Dillingham Boulevard to North King Street 12 2.4 North King Street to the H-1 Freeway 15 2.5 The H-1 Freeway to Houghtailing Street 17 2.6 Bridges 18 2.7 Architecturally Significant Structures 20 3 Civil Study Areas 3.1 Flood Capacity and Channel Design 22 3.2 Utilities 23 3.3 Stormwater Runoff and Drainage 25 3.4 Water Quality and Pollutant Sources 26 3.5 Canal Management and Maintenance 26 3.6 Tides 27 3.7 Sea Level Rise and Climate Change 27 3.8 Bathymetric and Topographic Surveys 28 3.9 Design Standards 28 3.10 Ecology & Marine Resources 29 4 Related Planning Studies 4.1 Primary Urban Center Development Plan for 2025 30 4.2 Kalihi-Palāma Action Plan 31 4.3 Kalihi Neighborhood Transit-Oriented Development Plan 33 4.4 Kapālama Canal: A Conceptual Plan Study 36 5 Jurisdiction, Land Ownership, and Regulations 5.1 Jurisdiction 37 5.2 Landowners 37 5.3 Landowner Development Plans 38 5.4 Revised Ordinances of Honolulu 39 5.5 Chapter 343 Hawai‘i Revised Statutes 40 5.6 Land Use Considerations 41 5.7 Other Required Permits/Regulatory Approvals 42 6 Community Design 43 7 References 46 7.1 Civil References 47 Appendix A : Cultural and Historical Brief A-1 Appendix B : Community Stakeholders B-1 Appendix C : Geotechnical Work Plan C-1 4 • EXISTING CONDITIONS REPORT - OCTOBER 2016 KAPĀLAMA CANAL CATALYTIC PROJECT 1 Introduction 1.1 Project Background & Location The Kapālama Canal Catalytic Project is based on various community plans supported by the City & County of Honolulu. -

State TOD Planning & Implementation Project, Island of Oahu, Final

State Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) Planning and Implementation Project for the Island of O‘ahu Prepared for: Office of Planning Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism Prepared by: July 2020 State TOD Planning & Implementation Project, Island of O‘ahu Study Context and Potential Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic This report was drafted between December 2019 and July 2020, with reference to consultations, data collection, and analyses between the third quarter of 2018 and the first weeks of 2020. From approximately February 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic caused major economic, social, and business disruptions in Hawai‘i, as it did worldwide. At the time of this writing, little data exists on the pandemic’s impacts on development markets and financing, and the timing of recovery is uncertain. The development visions presented herein reflect the long-term goals and aspirations of public agencies and private parties anticipated for each TOD priority area. Many of the projects described would not be expected to materialize for years or even decades of this study. The assessments presented in this report are tied to future implementation of the desired projects, and while some could be delayed, for purposes of this study, it is assumed that in this longer-term framework, conditions affecting such development in Hawai‘i could have recovered to be within the range of outcomes described herein. Nevertheless, prior to implementation of any particular project or financial mechanism, as for any development, the conclusions presented herein should be reviewed in the context of current market, economic, fiscal, political, and social environments. State TOD Planning & Implementation Project, Island of O‘ahu Acknowledgments The contributions and assistance from the following departments, agencies, and stakeholders in the preparation of the State Transit-Oriented Development Planning and Implementation Project for the Island of O‘ahu are gratefully acknowledged. -

City and County of Honolulu Department of Transportation Services Public Transit Division Title VI Program Report

City and County of Honolulu Department of Transportation Services Public Transit Division Title VI Program Report Department of Transportation Services City and County of Honolulu June, 2015 DRAFT Department of Transportation Services Public Transit Division Title VI Program Report June 2015 Department of Transportation Services City and County of Honolulu 650 South King Street Honolulu, HI 96813 DRAFT TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................... INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND .................................................................................................... DTS-PTD Overview................................................................................................................. Public Transit System Description ........................................................................................... FTA and Title VI/EJ ...................................................................................................................... Public Transportation Accommodation .................................................................................... PART I: GENERAL REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDELINES ........................................................................ General Requirements ............................................................................................................ 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................... -

AE47810E0128 Metro

JANUARY 2018 RFP No. AE47810E0128 Volume I – Technical Proposal (Appendices) Systems Engineering and Support Services Submitted by: Resumes Metro Systems Engineering and Support Services RFP No. AE47810E0128 TABLE OF CONTENTS Margaret (Meg) Cederoth, AICP, LEED AP | sustainability interface ....................................... R-49 Michael Harris-Gifford | program manager | corridor lead/ TO Andrew Cho | communications...................... R-50 manager | independent systems integration review team . R-1 Wilson Chu, EIT | ducktbank design .................. R-51 Jeff Goodling | deputy project manager | project controls lead | value engineering ............................ R-3 Joe Cochran | train control ......................... R-52 John Schnurbusch, PE | OCS manager ................ R-5 John Cockle, ASP | safety certification ................ R-53 Anh Le | communications manager | corridor lead/ TO Phil Collins | communications | independent systems manager ........................................ R-7 integration review team ............................ R-54 Barry Lemke | train control design lead................. R-9 Ramesh Daryani, PMP | systems integration . R-55 David Hetherington, PE | traction power manager ....... R-11 Ruperto Dilig, PE | independent quality manager ........ R-56 Davy Leung | RF engineering lead.................... R-13 Kurt Drummond, PE | communications................ R-57 Paul Mosier | operations and planning lead ............ R-15 Jeffrey Dugard | train control........................ R-58 Abbas Sizar, -

Global Report Global Metro Projects 2020.Qxp

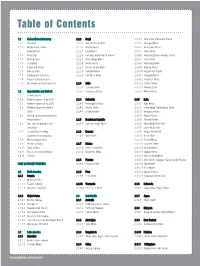

Table of Contents 1.1 Global Metrorail industry 2.2.2 Brazil 2.3.4.2 Changchun Urban Rail Transit 1.1.1 Overview 2.2.2.1 Belo Horizonte Metro 2.3.4.3 Chengdu Metro 1.1.2 Network and Station 2.2.2.2 Brasília Metro 2.3.4.4 Guangzhou Metro Development 2.2.2.3 Cariri Metro 2.3.4.5 Hefei Metro 1.1.3 Ridership 2.2.2.4 Fortaleza Rapid Transit Project 2.3.4.6 Hong Kong Mass Railway Transit 1.1.3 Rolling stock 2.2.2.5 Porto Alegre Metro 2.3.4.7 Jinan Metro 1.1.4 Signalling 2.2.2.6 Recife Metro 2.3.4.8 Nanchang Metro 1.1.5 Power and Tracks 2.2.2.7 Rio de Janeiro Metro 2.3.4.9 Nanjing Metro 1.1.6 Fare systems 2.2.2.8 Salvador Metro 2.3.4.10 Ningbo Rail Transit 1.1.7 Funding and financing 2.2.2.9 São Paulo Metro 2.3.4.11 Shanghai Metro 1.1.8 Project delivery models 2.3.4.12 Shenzhen Metro 1.1.9 Key trends and developments 2.2.3 Chile 2.3.4.13 Suzhou Metro 2.2.3.1 Santiago Metro 2.3.4.14 Ürümqi Metro 1.2 Opportunities and Outlook 2.2.3.2 Valparaiso Metro 2.3.4.15 Wuhan Metro 1.2.1 Growth drivers 1.2.2 Network expansion by 2025 2.2.4 Colombia 2.3.5 India 1.2.3 Network expansion by 2030 2.2.4.1 Barranquilla Metro 2.3.5.1 Agra Metro 1.2.4 Network expansion beyond 2.2.4.2 Bogotá Metro 2.3.5.2 Ahmedabad-Gandhinagar Metro 2030 2.2.4.3 Medellín Metro 2.3.5.3 Bengaluru Metro 1.2.5 Rolling stock procurement and 2.3.5.4 Bhopal Metro refurbishment 2.2.5 Dominican Republic 2.3.5.5 Chennai Metro 1.2.6 Fare system upgrades and 2.2.5.1 Santo Domingo Metro 2.3.5.6 Hyderabad Metro Rail innovation 2.3.5.7 Jaipur Metro Rail 1.2.7 Signalling technology 2.2.6 Ecuador -

The Following Documentation Is an Electronically‐ Submitted Vendor

The following documentation is an electronically‐ submitted vendor response to an advertised solicitation from the West Virginia Purchasing Bulletin within the Vendor Self‐Service portal at wvOASIS.gov. As part of the State of West Virginia’s procurement process, and to maintain the transparency of the bid‐opening process, this documentation submitted online is publicly posted by the West Virginia Purchasing Division at WVPurchasing.gov with any other vendor responses to this solicitation submitted to the Purchasing Division in hard copy format. Purchasing Division State of West Virginia 2019 Washington Street East Solicitation Response Post Office Box 50130 Charleston, WV 25305-0130 Proc Folder : 522404 Solicitation Description : Public Transportation Agency Safety Plan Proc Type : Central Master Agreement Date issued Solicitation Closes Solicitation Response Version 2019-01-23 SR 0805 ESR01231900000003378 1 13:30:00 VENDOR VS0000013500 TRANSPORTATION RESOURCE ASSOCIATES INC Solicitation Number: CRFQ 0805 PTR1900000004 Total Bid : $0.00 Response Date: 2019-01-23 Response Time: 12:05:25 Comments: FOR INFORMATION CONTACT THE BUYER Michelle L Childers (304) 558-2063 [email protected] Signature on File FEIN # DATE All offers subject to all terms and conditions contained in this solicitation Page : 1 FORM ID : WV-PRC-SR-001 Line Comm Ln Desc Qty Unit Issue Unit Price Ln Total Or Contract Amount 1 Public Transportation Agency Safety Plan Comm Code Manufacturer Specification Model # 94131503 Extended Description : Vendor MUST complete the ATTACHED Pricing Page, Exhibit A. If bidding electronically, vendor is to put $0.00 on the commodity line in WVOasis, complete the Excel pricing page, and upload into WVOasis as an attachment. -

Bus/Rail Integration Plan for the Kakaako Station Group

Bus/Rail Integration Plan for the Kaka‘ako Station Group Final April 2014 Prepared for: Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transportation Table of Contents 1 Introduction........................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Purpose of Bus/Rail Integration Plans ....................................................... 1 1.3 Basis for Bus/Rail Integration Plans ........................................................... 2 1.4 Contents of Bus/Rail Integration Plans ...................................................... 2 1.5 Monitoring of Factors Affecting Bus/Rail Integration Plans ........................ 3 1.6 Direction for Planning and Design of Bus Intermodal Facilities .................. 3 1.7 Direction for Planning and Design of Non-Bus Intermodal Facilities .......... 4 2 Bus/Rail Integration Plan Overview for the Kaka‘ako Station Group ................... 7 2.1 Factors Affecting the KSG Bus/Rail Integration Plan ................................. 7 3 Bus Networks Serving KSG Stations .................................................................. 10 3.1 Current Bus Network in the KSG ............................................................. 10 3.2 Planned Bus Network in KHSG Station Areas ......................................... 11 3.3 Bus Route Changes from FEIS ................................................................ 17 4 Recommended Bus Facilities at -

Global Mass Transit Report Information and Analysis on the Global Mass Transit Industry

NOVEMBER 2009 VOLUME I, ISSUE 1 Global Mass Transit Report Information and analysis on the global mass transit industry Contactless Ticketing in Mass Transit Mass Transit in South Africa A win-win solution for all stakeholders Governments invest heavily in transport infrastructure ith its myriad of advantages such as lower transaction costs, faster transaction speeds and multi-functionality, W s governments around the world acknowledge the contactless smart ticketing is the future of the global mass- important role that public transport plays in improving the transportation industry. Already operational in key metropolitan A quality of life, there is a global trend for increased investment in areas such as Hong Kong, London, Seoul, Washington D.C. and this important infrastructure sector. A commitment to upgrade Shanghai, contactless smart ticketing offers a win-win solution and expand mass transit systems has risen across the Americas, for transit operators and users, contactless technology developers Europe, Asia, and now in Africa as well. Taking the lead in Africa and financial institutions. is its biggest economy South Africa. Today, virtually all transit-fare payment systems in the For many years, South Africa boasted of the best transport delivery and procurement stages are opting for contactless infrastructure in the African continent. However, over the last ticketing as the primary medium. India’s Mumbai metro, which few years the transport infrastructure has been deteriorating. This is expected to become operational in 2011, will be equipped with is essentially owing to short sightedness and lack of continued a system based on contactless technology with reusable smart investment. It is only now that the transport sector has begun tickets. -

Icomera to Provide Dynamic Passenger Wi-Fi Solution for the Honolulu Rail Transit Project

Press release 08th October 2020 Icomera to provide Dynamic Passenger Wi-Fi Solution for the Honolulu Rail Transit Project ENGIE, through its subsidiary Icomera, is the world’s leading provider of wireless Internet connectivity for public transport. ENGIE is a world leading group that provides low-carbon energy and services, and has been working from its office in Honolulu for over a decade to help customers decarbonize, decentralize and digitalize their operations. Icomera has been awarded the contract to deliver high-speed Passenger Wi-Fi for the Honolulu Rail Transit Project, an elevated light rail system currently under construction in the City and County of Honolulu, O‘ahu, Hawai‘i. Icomera’s mobile connectivity solution will be deployed via its next-generation X5 mobile application and communications gateways, which will be installed on board 80 Hitachi train cars by early 2021. Empowering riders to stay connected, whether traveling for work or leisure, the X5 will deliver high- performance mobile Internet connectivity that will also meet and exceed passengers’ growing data transfer demands. Supported by a powerful suite of cloud-based management tools, the X-Series platform is capable of integrating a wide range of other Internet-enabled applications over time, giving the Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transportation (HART) a technological foundation to build a fully realized “digital train” of the future. This capacity to further customize the initial Wi-Fi roll-out adds to the solution’s overall ROI. Andrew Robbins, CEO of HART, shared, “We are pleased to be working together with the ENGIE and Icomera team to provide direct solutions that meet passengers’ expectations to stay digitally accessible and connected on the go. -

Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) - Compact, Mixed-Use Development Within Easy Walking Distance of a Transit Station

City and County of Honolulu Honolulu Live. Work. Connect It is easy to forget that at one time—over a half century ago — Oahu had street cars and trains. Even during the height of the post-World War II and statehood booms when the private automobile rose to prominence, Honolulu was developing an award-winning bus system. Today, daily bus ridership exceeds 200,000. The Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transportation (HART) rail transit system is the newest phase of the ongoing evolution of our island-wide multimodal transportation system. After more than three decades of planning, rapid transit is finally nearing fruition. The rail system will be fully integrated with our buses and roadway system. The rail component will serve as the spine of an island-wide multimodal transportation network that ushers mobility in the City and County of Honolulu into the 21st century. It will integrate with facilities in the Oahu Bike Plan and complete streets improvements. It will give us more choices in how we get around. Rail transit and higher-density development are also part of the City’s strategy to manage and direct growth. Channeling development pressure to rail station areas, most of which are already urbanized communities, will curb urban sprawl by encouraging infill development. This goal is possible through transit-oriented development (TOD) - compact, mixed-use development within easy walking distance of a transit station. TOD is designed to encourage walking, biking and transit, thereby creating more choices in both where we live and how we travel. Since this type of urban development uses land more efficiently, it will enable these communities to accommodate growth for many August 2017 generations. -

First Mile, Last Mile: How Federal Transit Funds Can Improve Access to Transit for People Who Walk and Bike

First Mile, Last Mile: How Federal Transit funds can improve access to transit for people who walk and bike This report looks at how biking and walking can be integrated with transit and the federal transit funds that can support projects and programs to increase accessibility among people who bike, walk, and take transit. August 2014 Table of Contents First Mile, Last Mile: How Federal Transit funds can improve access to transit for people who walk and bike .................................................................................................. 3 Who's walking and biking to transit? ..................................................................................... 3 Economic benefits ........................................................................................................... 4 Health benefits ................................................................................................................ 4 How can biking and walking be integrated with transit? ................................................. 4 Specific improvements .......................................................................................................... 5 Bike lanes ....................................................................................................................... 5 Bike parking .................................................................................................................... 5 Bikes on rail and ferries (“roll on accommodations”) ...................................................... -

Greening Iwilei and Kapalama, Honolulu, Hawaii | US EPA

June 2018 www.epa.gov/smartgrowth Greening America’s Communities Greening Iwilei and Kapalama Honolulu, Hawaii Office of Community Revitalization Smart Growth Program Greening America’s Communities Greening America’s Communities is an EPA program to help cities and towns develop an implementable vision of environmentally friendly neighborhoods that incorporate innovative green infrastructure and other sustainable design strategies. EPA provides design assistance to help support sustainable communities that protect the environment, economy, and public health and to inspire local and state leaders to expand this work elsewhere. Greening America’s Communities will help communities consider ways to incorporate sustainable design strategies into their planning and development to create and enhance interesting, distinctive neighborhoods that have multiple social, economic, and environmental benefts. Honolulu, Hawaii was chosen in 2016 as one of six communities to receive this assistance along with Columbia, South Carolina; Brownsville, Texas; Multnomah County, Oregon; Muscatine, Iowa, and Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. More information is available at: https://www.epa.gov/smartgrowth/greening-americas-communities All images courtesy of Community Design + Architecture unless otherwise noted. Acknowledgements U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Abby Hall, Offce of Community Revitalization Asia Yeary, Region 9 Hawaii Transportation Lead City and County of Honolulu Harrison Rue, Community Building and Transit-Oriented Development Administrator Renee Espiau, Transit-Oriented Development Division, Lead Planner, Department of Planning & Permitting Caterine Picardo Diaz, Transit-Oriented Development Division Planner, Department of Planning & Permitting Community Design + Architecture Connie Goldade, RLA, Principal in Charge Phil Erickson, AIA, Complete Streets Advisor Ashley Cruz, Urban Designer Katrina Majewski, Urban Designer Ariella Levitch, Urban Designer Roth Ecological Design International, LLC Lauren C.