Lemankoa 1920-1980 RFR Scragg.Pdf (PDF, 3.79MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Obsidian Sourcing Studies in Papua New Guinea Using Pixe

I A ••••'IWlf ilJIJIJj 1QJ OBSIDIAN SOURCING STUDIES IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA USING PIXE- PIGME ANALYSIS Glenn R Sumroerhayes (1), Roger Bird (2), Mike Hotchkiss(2), Chris Gosden (1), Jim Specht (3), Robin Torrence (3) and Richard Fullagar (3) (1) Department of Archaeology, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Vic 3083 (2) Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation, Private Mail Bag 1, Menai, NSW 2234 (3) Division of Anthropology, Australian Museum, P.O. Box A285, Sydney South, NSW 2000. Introduction The extraction and use of West New Britain obsidian has a twenty thousand year history in the western Pacific. It is found in prehistoric contexts from Malaysia in the west to Fiji in the east. Of significance is its spread out into the Pacific beginning at c.3500 B.P. It is found associated with the archaeological signature of this spread, Lapita pottery, in New Ireland, Mussau Island, South east Solomons, New Caledonia, Vanuatu, and Fiji. Yet the number of places where obsidian occurs naturally is few in number, making the study of obsidian found in archaeological contexts away from their sources a profitable area of research. The chemical characterisation of obsidian from the source area where it was extracted and the archaeological site where it was deposited provides important information on obsidian production, distribution and use patterns. The objective of this project is to study these patterns over a 20,00 year time span and identify changing distribution configurations in order to assess the significance of models of exchange patterns or social links in Pacific prehistory. To achieve this objective over 1100 pieces of obsidian from archaeological contexts and over 100 obsidian pieces from sources were analysed using PIXE-PIGME from 1990 to 1993. -

Federation of Catholic Bishops Conferences of Oceania Is Currently Meeting in Noumea, New Caledonia

Statement to the COP 21 meeting in Paris 2015 The Executive Committee of the Federation of Catholic Bishops Conferences of Oceania is currently meeting in Noumea, New Caledonia. As representatives of the Catholic Bishops’ Conferences of Australia, CEPAC (the Pacific Island nations), New Zealand, Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, we come from a multitude of island nation States spread throughout the Pacific. We are heartened by the growing international concern about Climate Change and Global Warming. Governments and international bodies are taking up the united cry of citizens to implement and monitor outcome focused policies to reduce practices and choices that impact negatively on the environment and thus on our peoples. Of particular concern to us are rising sea levels, ocean acidification, and unusual rainfall patterns. These are affecting many of our communities in a harmful way. In some cases, entire regions and nations are under threat from the indisputable fact of rising sea levels. Examples from this part of the world include the Carteret Islands, Fead Islands, Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, the Mortlock Islands, Nukumanu Islands, the Tokelau Islands, and Tuvalu. Efforts to build seawalls are largely ineffective against the rise of tides and consequently scarce fertile soil and cultivation areas are being destroyed rapidly. While offers of relocation are generous in themselves, uplifting a people from one place and planting them in another is a “solution” that is fraught with difficulty and at times even insensitivity to cultural identity and traditions. Pope Francis in his recent encyclical Laudato Si’ (on Care for our Common Home) invites – indeed urges – the entire global human family to see our planet and its peoples as our universal home. -

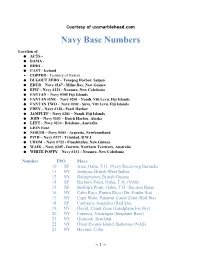

Navy Base Numbers

Courtesy of ussmarblehead.com Navy Base Numbers Location of: ACTS - BAMA - BIHO - CAST - Iceland COPPER - Territory of Hawaii DUGOUT ZERO – Tenapag Harbor, Saipan EDUR – Navy #167 - Milne Bay, New Guinea EPIC - Navy #131 - Noumea, New Caledonia FANTAN – Navy #305 Fiji Islands FANTAN ONE - Navy #201 - Nandi, Viti Levu, Fiji Islands FANTAN TWO - Navy #202 - Suva, Viti Levu, Fiji Islands FREY – Navy #128 - Pearl Harbor JAMPUFF – Navy #201 – Nandi, Fiji Islands JOIN – Navy #151 – Dutch Harbor, Alaska LEFT – Navy #134 - Brisbane, Australia LION Four NORTH – Navy #103 - Argentia, Newfoundland PITH – Navy #117 - Trinidad, B.W.I. UROM – Navy #722 - Finschhafen, New Guinea WAIK – Navy #245 - Darwin, Northern Territory, Australia WHITE POPPY – Navy #131 - Noumea, New Caledonia Number FPO Place 10 SF Aiea, Oahu, T.H. (Navy Receiving Barracks 11 NY Antigua, British West Indies 12 NY Georgetown, British Guiana 14 SF Barber's Point, Oahu, T.H. (NAS) 15 SF Bishop's Point, Oahu, T.H. (Section Base) 16 NY Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico (Dir. Finder Sta) 17 NY Cape Mala, Panama, Canal Zone (Rad Sta) 18 SF Canberra, Australia (Rad Sta) 19 NY David, Canal Zone (Landplane Facility) 20 NY Fonseca, Nicaragua (Seaplane Base) 21 NY Gourock, Scotland 22 NY Great Exuma Island, Bahamas (NAS) 23 NY Havana, Cuba ~ 1 ~ Courtesy of ussmarblehead.com 24 SF Hilo, Hawaii, T.H. (Section Base) 25 NY Hvalfjordur, Iceland (Navy Depot) 26 NY Ivigtut, Greenland (Nav Sta--later, Advance Base) 27 SF Kahului, Maui, T.H. (Section Base) 28 SF Kaneohe, Oahu, T.H. (NAS) 29 SF Keehi Lagoon, Honolulu, T.H. (NAS) 30 SF Puunene, Maui, T.H. -

Notornis June 04.Indd

Notornis, 2004, Vol. 51: 91-102 91 0029-4470 © The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. 2003 Birds of the northern atolls of the North Solomons Province of Papua New Guinea DON W. HADDEN P.O. Box 6054, Christchurch 8030, New Zealand [email protected] Abstract The North Solomons Province of Papua New Guinea consists of two main islands, Bougainville and Buka as well as several atolls to the north and east. The avifauna on five atolls, Nissan, Nuguria, Tulun, Takuu and Nukumanu, was recorded during visits in 2001. A bird list for each atoll group was compiled, incorporating previously published observations, and the local language names of birds recorded. Hadden, D.W. 2004. Birds of the northern atolls of the North Solomons Province of Papua New Guinea. Notornis 51(2): 91-102 Keywords bird-lists; Nissan; Nuguria; Tulun; Takuu; Nukumanu; Papua New Guinea; avifauna INTRODUCTION Grade 6 students had to be taken by Nukumanu North of Buka Island, in the North Solomons students. Over two days an examiner supervised Province of Papua New Guinea lie several small the exams and then the ship was able to return. atolls including Nissan (4º30’S 154º12’E), Nuguria, A third purpose of the voyage was to provide food also known as Fead (3º20’S 154º40’E), Tulun, also aid for the Tulun people. Possibly because of rising known as Carterets or Kilinailau (4º46’S 155º02’E), sea levels, the gardens of the Tulun atolls are now Takuu, also known as Tauu or Mortlocks (4º45’S too saline to grow vegetables. The atolls’ District 157ºE), and Nukumanu, also known as Tasmans Manager based in Buka is actively searching for (4º34’S 159º24’E). -

Listening to the Pacific

LISTENING TO THE PACIFIC FRAMEWORK FOR PACIFIC REGIONALISM REGIONAL INITIATIVE SUBMISSION TEMPLATE 2016 Page 1 of 6 FRAMEWORK FOR PACIFIC REGIONALISM – REGIONAL INITIATIVE TEMPLATE Please complete each section below. 1. Contact Details Please provide the following contact details: Name of individual or Caritas Aotearoa New Zealand group submitting initiative Name and position of Lisa Beech, Advocacy and Research Manager primary contact Email address [email protected] Phone number 0064-4-496-1742 Fax number 0064-4-499-2519 Mailing address PO Box 12193, Thorndon Wellington 6144 2. Name of Initiative Ensuring that climate finance adaptation funds reach the most vulnerable Pacific communities. Page 2 of 6 3. What is the common regional issue or challenge that this regional initiative aims to address? You may also want to address the following: What are the causes of this issue? Are there links to national, regional or international goals/policies? Please limit your response to no more than 750 words. Caritas Aotearoa New Zealand has undertaken research on how environmental issues affect our partners and networks throughout the Pacific region, which we have reported on in our 2014 foundational report: Small yet strong: Voices from Oceania on the environment and our first state of the environment in Oceania 2015 report Caring for our common home One of our key concerns is that despite the increasingly large sums of money made available for climate finance, this is not reaching some of the most vulnerable communities in our region, who are already living with significant impacts of climate change in the form of loss of homes from sea level rise, loss of food and water supplies, and increasingly unliveable conditions resulting from the impact of severe weather emergencies. -

IATA Codes for Papua New Guinea

IATA Codes for Papua New Guinea N.B. To check the official, current database of IATA Codes see: http://www.iata.org/publications/Pages/code-search.aspx City State IATA Code Airport Name Web Address Afore AFR Afore Airstrip Agaun AUP Aiambak AIH Aiambak Aiome AIE Aiome Aitape ATP Aitape Aitape TAJ Tadji Aiyura Valley AYU Aiyura Alotau GUR Ama AMF Ama Amanab AMU Amanab Amazon Bay AZB Amboin AMG Amboin Amboin KRJ Karawari Airstrip Ambunti AUJ Ambunti Andekombe ADC Andakombe Angoram AGG Angoram Anguganak AKG Anguganak Annanberg AOB Annanberg April River APR April River Aragip ARP Arawa RAW Arawa City State IATA Code Airport Name Web Address Arona AON Arona Asapa APP Asapa Aseki AEK Aseki Asirim ASZ Asirim Atkamba Mission ABP Atkamba Aua Island AUI Aua Island Aumo AUV Aumo Babase Island MKN Malekolon Baimuru VMU Baindoung BDZ Baindoung Bainyik HYF Hayfields Balimo OPU Bambu BCP Bambu Bamu BMZ Bamu Bapi BPD Bapi Airstrip Bawan BWJ Bawan Bensbach BSP Bensbach Bewani BWP Bewani Bialla, Matalilu, Ewase BAA Bialla Biangabip BPK Biangabip Biaru BRP Biaru Biniguni XBN Biniguni Boang BOV Bodinumu BNM Bodinumu Bomai BMH Bomai Boridi BPB Boridi Bosset BOT Bosset Brahman BRH Brahman 2 City State IATA Code Airport Name Web Address Buin UBI Buin Buka BUA Buki FIN Finschhafen Bulolo BUL Bulolo Bundi BNT Bundi Bunsil BXZ Cape Gloucester CGC Cape Gloucester Cape Orford CPI Cape Rodney CPN Cape Rodney Cape Vogel CVL Castori Islets DOI Doini Chungribu CVB Chungribu Dabo DAO Dabo Dalbertis DLB Dalbertis Daru DAU Daup DAF Daup Debepare DBP Debepare Denglagu Mission -

AAB PNG Evaluation Report

The adapting atolls Final evaluation of the project “Community-based adaptation to climate change (CBA CC)” in Nissan district, Papua New Guinea i | Evaluation report | The CBA CC project in Nissan district, Papua New Guinea Abbreviations ABG Autonomous Bougainville Government ANCP Australian NGO Cooperation Program AUD Australian Dollar BEB Bougainville Education Board BOUTHA Bougainville Traditional Health Association BWF Bougainville Women’s Federation CBA Community-based adaptation CBCCAG Community-based Climate Change Action Grants Program CCA Climate Change Adaptation CCA Climate change adaptation CoE Council of Elders CVCA Climate Vulnerability and Capacity Assessment DFAT Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Australia) DMO Disaster Management Office DRR Disaster risk reduction EC European Commission FCS Food Consumption Score GEF Global Environment Facility IPCC Inter-Governmental Panel on Climate Change IPM Integrated pest management MSC Most Significant Change NARI National Agricultural Research Institute NDA Nissan District Administration NGO Non-Governmental Organisation OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development PGK Papua New Guinea Kina PMERL Participatory Monitoring, Evaluation, Reflection and Learning PNG Papua New Guinea PPS Probability Proportional to Size ToR Terms of reference USAID United States Agency for International Development WASH Water, Sanitation and Hygiene The CBA CC project in Nissan district, Papua New Guinea | Evaluation report | ii The adapting atolls. Final evaluation of the project “Community-based adaptation to climate change in Nissan district (CBA CC)” in Papua New Guinea This report presents the final evaluation results of the project “Community-based adaptation to climate change in Nissan district (CBA CC)”. CARE implemented this project between July 2012 and April 2015 with funding from the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) under its Community-based Climate Change Action Grants (CBCCAG) program. -

VII the Eastern Islands (Nuguria, Tauu and Nukumanu)

THE EASTERN ISLANDS (NUGURIA, TAUU AND NUKUMANU) VII The Eastern Islands (Nuguria, Tauu and Nukumanu) ast of the large Melanesian islands extends a For years the population has been in the process Elong chain of small islands, mostly raised of dying out. The current number is about fifteen. coral reefs or atolls, belonging geographically to In 1902 alone, sixteen died, particularly as a result Melanesia, but occupying a quite special position of influenza. The natives’ physical resistance seems ethnographically. to be very low, and it will not be many more years Three of these small atolls, Nuguria, Tauu and before none of the present population exists. In Nukumanu, have been annexed by the German 1885 when I first visited this small group I esti- protectorate. A fourth group, Liueniua or Ong mated the population to be at least 160 people. tong Java, by far the most significant, was Ger - Tauu, pronounced Tau’u’u (Mortlock or Mar- man for a time but then by treaty passed into queen Islands; Dr Thilenius names it incorrectly as English hands. Taguu), is likewise an atoll structure. It lies at ap- Although the three German groups are of no proximately 157ºE longitude and 4º50’S latitude, great interest commercially and probably never and the total land area of the islands is no greater will be, ethnographically they are of no small im- than 200 hectares. The distance from Nuguria is portance because in spite of being in a Melanesian about 150 nautical miles. The nearest point in the neighbourhood, they are inhabited by Polynesians. -

Ressources Marines Et Traditions, Bulletin D'information De La CPS N°20

Secrétariat général ISSN 1025-7489 de la Communauté du Pacifique Numéro 20 - Mars 2007 RESSOURCES MARINES ET TRADITIONS bulletin d’information Éditorial Sommaire Le présent numéro contient des articles qui expriment des points de vue diver- L’évolution du pêcheur artisanal : l’exemple des Îles Salomon et gents, ce dont nous nous félicitons. Espérons qu’en secouant le cocotier, nous de la Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée provoquerons quelques réactions. A. Sabetian et S. Foale p. 3 Dans le premier article, “L’évolution du pêcheur artisanal : l’exemple des Gestion traditionnelle des ressources Îles Salomon et de la Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée”, Armagan Sabetian et marines à Vanuatu : reconnaître, appuyer Simon Foale examinent les gains de productivité obtenus grâce à l’adop- et renforcer les systèmes autochtones tion de nouvelles techniques sur l’île de Ghizo, dans la province occiden- de gestion des ressources tale des Îles Salomon, et dans celle de Milne Bay, en Papouasie-Nouvelle- F.R. Hickey p. 11 Guinée. Ces études de cas confirment que ce sont jusqu’à présent des den- sités de population humaine très faibles qui ont protégé de nombreuses Socialisation des connaissances pêcheries des Îles Salomon et de Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée, et non une halieutiques : émergence et transmission forme quelconque de “gestion traditionnelle” ou d’éthique de la conserva- de nouvelles techniques de pêche et tion. Les auteurs montrent que les pêcheurs ignorent généralement le fait des connaissances écologiques sur le que les stocks qu’ils exploitent sont limités. Par conséquent, en l’absence milieu marin en République de Palau, Micronésie occidentale de mesure systématique de gestion, les nouvelles techniques et l’expansion des marchés d’exportation vers l’Asie accéléreront la surpêche progressive. -

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands First compiled by Nancy Sack and Gwen Sinclair Updated by Nancy Sack Current to January 2020 Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands Background An inquiry from a librarian in Micronesia about how to identify subject headings for the Pacific islands highlighted the need for a list of authorized Library of Congress subject headings that are uniquely relevant to the Pacific islands or that are important to the social, economic, or cultural life of the islands. We reasoned that compiling all of the existing subject headings would reveal the extent to which additional subjects may need to be established or updated and we wish to encourage librarians in the Pacific area to contribute new and changed subject headings through the Hawai‘i/Pacific subject headings funnel, coordinated at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.. We captured headings developed for the Pacific, including those for ethnic groups, World War II battles, languages, literatures, place names, traditional religions, etc. Headings for subjects important to the politics, economy, social life, and culture of the Pacific region, such as agricultural products and cultural sites, were also included. Scope Topics related to Australia, New Zealand, and Hawai‘i would predominate in our compilation had they been included. Accordingly, we focused on the Pacific islands in Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia (excluding Hawai‘i and New Zealand). Island groups in other parts of the Pacific were also excluded. References to broader or related terms having no connection with the Pacific were not included. Overview This compilation is modeled on similar publications such as Music Subject Headings: Compiled from Library of Congress Subject Headings and Library of Congress Subject Headings in Jewish Studies. -

Download 676.32 KB

Social Safeguard Monitoring Report Semi-annual Report September 2020 Maritime and Waterways Safety Project Reporting period covering January-June 2020. Prepared by National Maritime Safety Authority for the Asian Development Bank. This semi-annual social monitoring report is a document of the Borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgements as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. National Maritime Safety Authority Maritime and Waterways Safety Project Project Number: 44375-013 Loan Number: 2978-PNG: Maritime and Waterways Safety Project Social Safeguard Monitoring Report Period Covering: January – June 2020 Prepared by: National Maritime Safety Authority September 2020 2 Table of Contents ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................................................... 4 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 5 1. PROJECT OVERVIEW .......................................................................................................... 6 2. METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................. -

Culture, Capitalism and Contestation Over Marine Resources in Island Melanesia

Changing Lives and Livelihoods: Culture, Capitalism and Contestation over Marine Resources in Island Melanesia Jeff Kinch 31st March 2020 A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Archaeology and Anthropology Research School of Humanities and the Arts College of Arts and Social Sciences Australian National University Declaration Except where other information sources have been cited, this thesis represents original research undertaken by me for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology at the Australian National University. I testify that the material herein has not been previously submitted in whole or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. Jeff Kinch Supervisory Panel Prof Nicolas Peterson Principal Supervisor Assoc Prof Simon Foale Co-Supervisor Dr Robin Hide Co-Supervisor Abstract This thesis is both a contemporary and a longitudinal ethnographic case study of Brooker Islanders. Brooker Islanders are a sea-faring people that inhabit a large marine territory in the West Calvados Chain of the Louisiade Archipelago in Milne Bay Province of Papua New Guinea. In the late 19th Century, Brooker Islanders began to be incorporated into an emerging global economy through the production of various marine resources that were desired by mainly Australian capitalist interests. The most notable of these commodified marine resources was beche-de-mer. Beche-de-mer is the processed form of several sea cucumber species. The importance of the sea cucumber fishery for Brooker Islanders waned when World War I started. Following the rise of an increasingly affluent China in the early 1990s, the sea cucumber fishery and beche-de-mer trade once again became an important source of cash income for Brooker Islanders.