AAB PNG Evaluation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Obsidian Sourcing Studies in Papua New Guinea Using Pixe

I A ••••'IWlf ilJIJIJj 1QJ OBSIDIAN SOURCING STUDIES IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA USING PIXE- PIGME ANALYSIS Glenn R Sumroerhayes (1), Roger Bird (2), Mike Hotchkiss(2), Chris Gosden (1), Jim Specht (3), Robin Torrence (3) and Richard Fullagar (3) (1) Department of Archaeology, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Vic 3083 (2) Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation, Private Mail Bag 1, Menai, NSW 2234 (3) Division of Anthropology, Australian Museum, P.O. Box A285, Sydney South, NSW 2000. Introduction The extraction and use of West New Britain obsidian has a twenty thousand year history in the western Pacific. It is found in prehistoric contexts from Malaysia in the west to Fiji in the east. Of significance is its spread out into the Pacific beginning at c.3500 B.P. It is found associated with the archaeological signature of this spread, Lapita pottery, in New Ireland, Mussau Island, South east Solomons, New Caledonia, Vanuatu, and Fiji. Yet the number of places where obsidian occurs naturally is few in number, making the study of obsidian found in archaeological contexts away from their sources a profitable area of research. The chemical characterisation of obsidian from the source area where it was extracted and the archaeological site where it was deposited provides important information on obsidian production, distribution and use patterns. The objective of this project is to study these patterns over a 20,00 year time span and identify changing distribution configurations in order to assess the significance of models of exchange patterns or social links in Pacific prehistory. To achieve this objective over 1100 pieces of obsidian from archaeological contexts and over 100 obsidian pieces from sources were analysed using PIXE-PIGME from 1990 to 1993. -

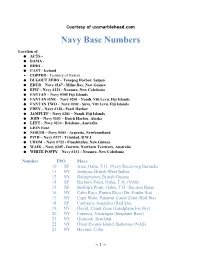

Navy Base Numbers

Courtesy of ussmarblehead.com Navy Base Numbers Location of: ACTS - BAMA - BIHO - CAST - Iceland COPPER - Territory of Hawaii DUGOUT ZERO – Tenapag Harbor, Saipan EDUR – Navy #167 - Milne Bay, New Guinea EPIC - Navy #131 - Noumea, New Caledonia FANTAN – Navy #305 Fiji Islands FANTAN ONE - Navy #201 - Nandi, Viti Levu, Fiji Islands FANTAN TWO - Navy #202 - Suva, Viti Levu, Fiji Islands FREY – Navy #128 - Pearl Harbor JAMPUFF – Navy #201 – Nandi, Fiji Islands JOIN – Navy #151 – Dutch Harbor, Alaska LEFT – Navy #134 - Brisbane, Australia LION Four NORTH – Navy #103 - Argentia, Newfoundland PITH – Navy #117 - Trinidad, B.W.I. UROM – Navy #722 - Finschhafen, New Guinea WAIK – Navy #245 - Darwin, Northern Territory, Australia WHITE POPPY – Navy #131 - Noumea, New Caledonia Number FPO Place 10 SF Aiea, Oahu, T.H. (Navy Receiving Barracks 11 NY Antigua, British West Indies 12 NY Georgetown, British Guiana 14 SF Barber's Point, Oahu, T.H. (NAS) 15 SF Bishop's Point, Oahu, T.H. (Section Base) 16 NY Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico (Dir. Finder Sta) 17 NY Cape Mala, Panama, Canal Zone (Rad Sta) 18 SF Canberra, Australia (Rad Sta) 19 NY David, Canal Zone (Landplane Facility) 20 NY Fonseca, Nicaragua (Seaplane Base) 21 NY Gourock, Scotland 22 NY Great Exuma Island, Bahamas (NAS) 23 NY Havana, Cuba ~ 1 ~ Courtesy of ussmarblehead.com 24 SF Hilo, Hawaii, T.H. (Section Base) 25 NY Hvalfjordur, Iceland (Navy Depot) 26 NY Ivigtut, Greenland (Nav Sta--later, Advance Base) 27 SF Kahului, Maui, T.H. (Section Base) 28 SF Kaneohe, Oahu, T.H. (NAS) 29 SF Keehi Lagoon, Honolulu, T.H. (NAS) 30 SF Puunene, Maui, T.H. -

Notornis June 04.Indd

Notornis, 2004, Vol. 51: 91-102 91 0029-4470 © The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. 2003 Birds of the northern atolls of the North Solomons Province of Papua New Guinea DON W. HADDEN P.O. Box 6054, Christchurch 8030, New Zealand [email protected] Abstract The North Solomons Province of Papua New Guinea consists of two main islands, Bougainville and Buka as well as several atolls to the north and east. The avifauna on five atolls, Nissan, Nuguria, Tulun, Takuu and Nukumanu, was recorded during visits in 2001. A bird list for each atoll group was compiled, incorporating previously published observations, and the local language names of birds recorded. Hadden, D.W. 2004. Birds of the northern atolls of the North Solomons Province of Papua New Guinea. Notornis 51(2): 91-102 Keywords bird-lists; Nissan; Nuguria; Tulun; Takuu; Nukumanu; Papua New Guinea; avifauna INTRODUCTION Grade 6 students had to be taken by Nukumanu North of Buka Island, in the North Solomons students. Over two days an examiner supervised Province of Papua New Guinea lie several small the exams and then the ship was able to return. atolls including Nissan (4º30’S 154º12’E), Nuguria, A third purpose of the voyage was to provide food also known as Fead (3º20’S 154º40’E), Tulun, also aid for the Tulun people. Possibly because of rising known as Carterets or Kilinailau (4º46’S 155º02’E), sea levels, the gardens of the Tulun atolls are now Takuu, also known as Tauu or Mortlocks (4º45’S too saline to grow vegetables. The atolls’ District 157ºE), and Nukumanu, also known as Tasmans Manager based in Buka is actively searching for (4º34’S 159º24’E). -

IATA Codes for Papua New Guinea

IATA Codes for Papua New Guinea N.B. To check the official, current database of IATA Codes see: http://www.iata.org/publications/Pages/code-search.aspx City State IATA Code Airport Name Web Address Afore AFR Afore Airstrip Agaun AUP Aiambak AIH Aiambak Aiome AIE Aiome Aitape ATP Aitape Aitape TAJ Tadji Aiyura Valley AYU Aiyura Alotau GUR Ama AMF Ama Amanab AMU Amanab Amazon Bay AZB Amboin AMG Amboin Amboin KRJ Karawari Airstrip Ambunti AUJ Ambunti Andekombe ADC Andakombe Angoram AGG Angoram Anguganak AKG Anguganak Annanberg AOB Annanberg April River APR April River Aragip ARP Arawa RAW Arawa City State IATA Code Airport Name Web Address Arona AON Arona Asapa APP Asapa Aseki AEK Aseki Asirim ASZ Asirim Atkamba Mission ABP Atkamba Aua Island AUI Aua Island Aumo AUV Aumo Babase Island MKN Malekolon Baimuru VMU Baindoung BDZ Baindoung Bainyik HYF Hayfields Balimo OPU Bambu BCP Bambu Bamu BMZ Bamu Bapi BPD Bapi Airstrip Bawan BWJ Bawan Bensbach BSP Bensbach Bewani BWP Bewani Bialla, Matalilu, Ewase BAA Bialla Biangabip BPK Biangabip Biaru BRP Biaru Biniguni XBN Biniguni Boang BOV Bodinumu BNM Bodinumu Bomai BMH Bomai Boridi BPB Boridi Bosset BOT Bosset Brahman BRH Brahman 2 City State IATA Code Airport Name Web Address Buin UBI Buin Buka BUA Buki FIN Finschhafen Bulolo BUL Bulolo Bundi BNT Bundi Bunsil BXZ Cape Gloucester CGC Cape Gloucester Cape Orford CPI Cape Rodney CPN Cape Rodney Cape Vogel CVL Castori Islets DOI Doini Chungribu CVB Chungribu Dabo DAO Dabo Dalbertis DLB Dalbertis Daru DAU Daup DAF Daup Debepare DBP Debepare Denglagu Mission -

Download 676.32 KB

Social Safeguard Monitoring Report Semi-annual Report September 2020 Maritime and Waterways Safety Project Reporting period covering January-June 2020. Prepared by National Maritime Safety Authority for the Asian Development Bank. This semi-annual social monitoring report is a document of the Borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgements as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. National Maritime Safety Authority Maritime and Waterways Safety Project Project Number: 44375-013 Loan Number: 2978-PNG: Maritime and Waterways Safety Project Social Safeguard Monitoring Report Period Covering: January – June 2020 Prepared by: National Maritime Safety Authority September 2020 2 Table of Contents ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................................................... 4 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 5 1. PROJECT OVERVIEW .......................................................................................................... 6 2. METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................. -

Culture, Capitalism and Contestation Over Marine Resources in Island Melanesia

Changing Lives and Livelihoods: Culture, Capitalism and Contestation over Marine Resources in Island Melanesia Jeff Kinch 31st March 2020 A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Archaeology and Anthropology Research School of Humanities and the Arts College of Arts and Social Sciences Australian National University Declaration Except where other information sources have been cited, this thesis represents original research undertaken by me for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology at the Australian National University. I testify that the material herein has not been previously submitted in whole or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. Jeff Kinch Supervisory Panel Prof Nicolas Peterson Principal Supervisor Assoc Prof Simon Foale Co-Supervisor Dr Robin Hide Co-Supervisor Abstract This thesis is both a contemporary and a longitudinal ethnographic case study of Brooker Islanders. Brooker Islanders are a sea-faring people that inhabit a large marine territory in the West Calvados Chain of the Louisiade Archipelago in Milne Bay Province of Papua New Guinea. In the late 19th Century, Brooker Islanders began to be incorporated into an emerging global economy through the production of various marine resources that were desired by mainly Australian capitalist interests. The most notable of these commodified marine resources was beche-de-mer. Beche-de-mer is the processed form of several sea cucumber species. The importance of the sea cucumber fishery for Brooker Islanders waned when World War I started. Following the rise of an increasingly affluent China in the early 1990s, the sea cucumber fishery and beche-de-mer trade once again became an important source of cash income for Brooker Islanders. -

Filmed By/For the National Archives of Papua New Guinea, PORT MORESBY - 1989

NATIONAL ARCHIVES & PUBLIC RECORDS SERVICES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA PATROL REPORTS DISTRICT: Bougainville STATION: Buka VOLUME No: 4 ACCESSION No: 496. 1962 - 1963 Filmed by/for the National Archives of Papua New Guinea, PORT MORESBY - 1989. Sole Custodian: National Archives of Papua New Guinea. Papua New Guinea Patrol Reports Digitized version made available by The Library UC SAN DIEGO"7 Copyright: Government of Papua New Guinea. This digital version made under a license granted by the National Archives and Public Records Services of Papua New Guinea. Use: This digital copy of the work is intended to support research, teaching, and private study. Constraints: This work is protected by the U.S. Copyright Law (Title 17, U.S.C.) and the laws of Papua New Guinea. Use of this work beyond that allowed by “fair use" requires written permission of the National Archives of Papua New Guinea. Responsibility for obtaining permissions and any use and distribution of this work rests exclusively with the user and not the UC San Diego Library. Note on digitized version: A microfiche copy of these reports is held at the University of California, San Diego (Mandeville Special Collections Library, MSS 0215). The digitized version presented here reflects the quality and contents of the microfiche. Problems which have been identified include misfiled reports, out-of-order pages, illegible text; these problems have been rectified whenever possible. The original reports are in the National Archives of Papua New Guinea (Accession no. 496). PATROL REPORT OF: Buka Passage ACCESSION No. 496 VOL. No: 4 : 1962 - 1963 NUMBER OF REPORTS: 6 MAPS/ PERIOD OF PATROL REPORT NO: FOLIO OFFICER CONDUCTING PATROL AREA PATROLLED PHOTOS [1] 9a- 62/63 l-11 Rochfort Peter CPO Cartaret Islands Calso refered as 10-62/63 1 map 17/12/62-20/12-62 [2]12-62/63 Reading J.M. -

Syntactic Ergativity in Nehan Written Byy John J

Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics Thesis approval Sheet This thesis, entitled Syntactic Ergativity in Nehan Written byy John J. Glennon and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with major in Applied Linguistics has been read and approved by the undersigned members of the faculty of the Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics Paul Kroeger (Supervising Professor) a Tod Allman Japet Allen 6-Am-2o14 Date signed SYNTACTIC ERGATIVITY IN NEHAN By John J. Glennon Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with major in Applied Linguistics Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics December 2014 © 2014 John J. Glennon All Rights Reserved CERTIFICATE I acknowledge that use of copyrighted material in my thesis may place me under an such material exceeds usual fair obligation to the copyright owner, especially when use of use provisions. I hereby certify that I have obtained the written permission of the of thesis has copyright owner for any and all such occurrences and that no portion my been copyrighted previously unless properly referenced. I hereby agree to indemnify and hold harmless the Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics from any and all claims that violation. may be asserted or that may arise from any copyright Signature Argys_z0/ Date THESIS DUPLICATION RELEASE I hereby authorize the Graduate Institute of Applied Linguisties Library to duplicate this thesis when needed for research and/or scholarship. Agreed: Refused: ABSTRACT Syntactic Ergativity in Nehan John J. Glennon Master of Arts with major in Applied Linguistics The Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics, December 2014 Supervising Professor: Paul Kroeger In this thesis, I argue that Nehan is a syntactically ergative language. -

Terra Australis 26

terra australis 26 Terra Australis reports the results of archaeological and related research within the south and east of Asia, though mainly Australia, New Guinea and island Melanesia — lands that remained terra australis incognita to generations of prehistorians. Its subject is the settlement of the diverse environments in this isolated quarter of the globe by peoples who have maintained their discrete and traditional ways of life into the recent recorded or remembered past and at times into the observable present. Since the beginning of the series, the basic colour on the spine and cover has distinguished the regional distribution of topics as follows: ochre for Australia, green for New Guinea, red for South-East Asia and blue for the Pacific Islands. From 2001, issues with a gold spine will include conference proceedings, edited papers and monographs which in topic or desired format do not fit easily within the original arrangements. All volumes are numbered within the same series. List of volumes in Terra Australis Volume 1: Burrill Lake and Currarong: Coastal Sites in Southern New South Wales. R.J. Lampert (1971) Volume 2: Ol Tumbuna: Archaeological Excavations in the Eastern Central Highlands, Papua New Guinea. J.P. White (1972) Volume 3: New Guinea Stone Age Trade: The Geography and Ecology of Traffic in the Interior. I. Hughes (1977) Volume 4: Recent Prehistory in Southeast Papua. B. Egloff (1979) Volume 5: The Great Kartan Mystery. R. Lampert (1981) Volume 6: Early Man in North Queensland: Art and Archaeology in the Laura Area. A. Rosenfeld, D. Horton and J. Winter (1981) Volume 7: The Alligator Rivers: Prehistory and Ecology in Western Arnhem Land. -

Project Final Evaluation: “Improving Community Climate Resilience in Nissan”, Autonomous Region of Bougainville, Papua New Guinea

Project Final Evaluation: “Improving Community Climate Resilience in Nissan”, Autonomous Region of Bougainville, Papua New Guinea Edward Boydell and Ingvar Anda June 2017 (DRAFT to CARE) Authors & Contributors This final evaluation report was prepared for CARE International in Papua New Guinea by Edward Boydell – and Ingvar Anda – Hau Meni & Associates - www.haumeni.com Fieldwork and data collection conducted by Edward Boydell, Chris Binabat, Rebecca Jinro, Loretta Titus and Naomi Basika. This paper is made possible by the generous support of the American people, through the United States Agency for International Development Disclaimer The views in this paper are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent those of the CARE or its programs, USAID, the Government of the United States of America /any other partners. Cover page photo: detail of a carving by the Pinepel Cultural Group, highlighting the various components of the project. This was presented to CARE during the project closure ceremony in March 2017. Image: E. Boydell. 2 Executive Summary CARE International in PNG is supporting women and men living on Nissan and Pinepel Island to build resilience to the impacts of climate change. The communities that live on these remote coral atolls in the Autonomous Region of Bougainville are highly exposed to the impacts of climate change. Support has been provided the ”Improving Community Resilience in Nissan” project since April 2015. The overall objective of the project is: “Increased community resilience to the impacts of climate change, through improved coastal and marine resource management and enhanced livelihoods in Nissan District” The project is funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through the Pacific American Climate Fund (PACAM). -

Alternativeislandnamesmel.Pdf

Current Name Historical Names Position Isl Group Notes Abgarris Abgarris Islands, Fead Islands, Nuguria Islands 3o10'S 155oE, Bismarck Arch. PNG Aion 4km S Woodlark, PNG Uninhabited, forest on sandbar, Raised reef - being eroded. Ajawi Geelvink Bay, Indonesia Akib Hermit Atoll having these four isles and 12 smaller ones. PNG Akiri Extreme NW near Shortlands Solomons Akiki W side of Shortlands, Solomons Alcester Alacaster, Nasikwabu, 6 km2 50 km SW Woodlark, Flat top cliffs on all sides, little forest elft 2005, PNG Alcmene 9km W of Isle of Pines, NC NC Alim Elizabeth Admiralty Group PNG Alu Faisi Shortland group Solomons Ambae Aoba, Omba, Oba, Named Leper's Island by Bougainville, 1496m high, Between Santo & Maewo, Nth Vanuatu, 15.4s 167.8e Vanuatu Amberpon Rumberpon Off E. coast of Vegelkop. Indonesia Amberpon Adj to Vogelkop. Indonesia Ambitle Largest of Feni (Anir) Group off E end of New Ireland, PNG 4 02 27s 153 37 28e Google & RD atlas of Aust. Ambrym Ambrim Nth Vanuatu Vanuatu Anabat Purol, Anobat, In San Miguel group,(Tilianu Group = Local name) W of Rambutyo & S of Manus in Admiralty Group PNG Anagusa Bentley Engineer Group, Milne Bay, 10 42 38.02S 151 14 40.19E, 1.45 km2 volcanic? C uplifted limestone, PNG Dumbacher et al 2010, Anchor Cay Eastern Group, Torres Strait, 09 22 s 144 07e Aus 1 ha, Sand Cay, Anchorites Kanit, Kaniet, PNG Anatom Sth Vanuatu Vanuatu Aneityum Aneiteum, Anatom Southernmost Large Isl of Vanuatu. Vanuatu Anesa Islet off E coast of Bougainville. PNG Aniwa Sth Vanuatu Vanuatu Anuda Anuta, Cherry Santa Cruz Solomons Anusugaru #3 Island, Anusagee, Off Bougainville adj to Arawa PNG Aore Nestled into the SE corner of Santo and separated from it by the Segond Canal, 11 x 9 km. -

Fisheries Management Act 1998 the National Beche-De-Mer Fishery

Fisheries Management Act 1998 The National Beche-de-mer Fishery Management Plan I, Honorable Andrew Baing M.P Minister for Fisheries by virtue of the powers conferred by Section 28 of the Fisheries Management Act 1998, and all other powers me enabling set out the revised national bêche-de-mer fishery management plan. This plan supersedes the previous plan and takes effect from the date of notification in the National Gazette. Background Description of the Fishery The increasing demand for bêche-de-mer from Asian market and their over-exploitation in some of the neighboring Pacific Island Countries has caused the introduction of tough management regime to control the harvest of the fishery, but more importantly maintain resources sustainability. In the past only a handful of beche-de-mer species were considered most valuable, but rapid declined in abundance of these group in the last 20 years has led the less favoured species being harvested increasingly. Today there are currently 20 different species being harvested commercially in PNG. There has been a marked declined in the volume of high value species and an increase in the volume of the low value species taken. The opening of the market to new species that traditionally had no commercial value has dramatically impacted on the volume of export. Figures for 2000 showed PNG exported about 607mt valued about K16.2 million. Of that the low value species accounted for 61% (370mt) and high value species made up the remaining. In 2001 PNG exported 484mt value about K17.2 million and again the low value species accounted for more than 60% of the total export.