Japan-India Security Cooperation Building a Solid Foundation Amid Uncertainty Shutaro Sano1 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vb W Previous Ag

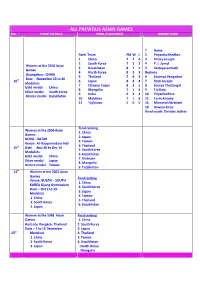

ALL PREVIOUS ASIAN GAMES No. EVENT DETAILS FINAL STANDINGS INDIAN TEAM ? Name Rank Team Pld W L 2 Priyanka Khedkar 1 China 7 7 0 3 Princy Joseph 2 South Korea 7 5 2 4 P. J. Jomol Women at the 2010 Asian 3 Kazakhstan 8 7 1 5 Kattuparambath Games 4 North Korea 8 5 3 Reshma Guangzhou - CHINA 5 Thailand 7 4 3 6 Soumya Vengadan Date November 13 to 26 16th 6 Japan 8 4 4 7 Shibi Joseph Medalists 7 Chinese Taipei 8 3 5 8 Soorya Thottangal Gold medal China 8 Mongolia 7 1 6 9 Tiji Raju Silver medal South Korea 9 India 6 2 4 10 Priyanka Bora Bronze medal Kazakhstan 10 Maldives 7 1 6 12 Terin Antony 11 Tajikistan 5 0 5 16 Minomol Abraham 18 Aswani Kiran Head coach: Devidas Jadhav Final ranking Women at the 2006 Asian 1. China Games 2. Japan DOHA - QATAR 3. Taiwan Venue Al-Rayyan Indoor Hall 4. Thailand 15th Date Nov 26 to Dec 14 5. South Korea Medalists 6. Kazakhstan Gold medal China 7. Vietnam Silver medal Japan 8. Mongolia Bronze medal Taiwan 9. Tadjikistan 14th Women at the 2002 Asian Games Final ranking Venue: BUSAN – SOUTH 1. China KOREA Gijang Gymnasium 2. South Korea Date :- Oct 2 to 13 3. Japan Medalists 4. Taiwan 1 China 5. Thailand 2 South Korea 6. Kazakhstan 3 Japan Women at the 1998 Asian Final ranking Games 1. China Host city Bangkok, Thailand 2. South Korea Date :- 7 to 15 December 3. Japan 13th Medalists 4. -

Introduction

CHAPTER – 1 INTRODUCTION Delhi is a symbol of India’s culturally rich past and thriving present. Apart from being a political centre of India, Delhi is also a commercial, transport and cultural hub, making it a city most cherished and visited by all. These factors have given the route to host the inaugural 1951 Asian Games, 1982 Asian Games, 1983 NAM Summit, 2010 Men's Hockey World Cup, 2010 Commonwealth Games, 2012 BRICS Summit, one of the major host cities of the 2011 Cricket World Cup, which have glorified Delhi’s fame all over the world. It has state-of-the-art healthcare, transport, and public services. Delhi represents a beautiful amalgamation of ancient culture and modernity. 2. A varied history has left behind a rich architectural and cultural heritage in Delhi. In the words of famous Urdu poet, Mir Taqi Mir, Delhi’s streets were not alleys but parchment of a painting, every face that appeared, seemed to be a masterpiece. On one side it has Old Delhi, narrow lanes rich in history and fragrances of food as unique as Old Delhi, and on the other side, it has New Delhi which has lush green areas of the Lutyens and diplomatic zones. 3. Delhi has also been famous for its various gardens and botanical parks. The Garden of Five Senses, the Lodi Gardens, the Mughal Gardens, the Buddha Jayanti Park, and Nehru Park are some of the gardens famous among the people of the city. The city has several historical monuments that are highly treasured by the country. Delhi is home to some of the nation’s best collection of art galleries and museums, which showcase everything from ancient antiquities to contemporary art. -

SHIVAJI UNIVERSITY, KOLHAPUR Board of Sports and Physical Culture (B.O.S.P.C.) Members of the Committee

SHIVAJI UNIVERSITY, KOLHAPUR Board of Sports and Physical Culture (B.O.S.P.C.) Members of the Committee Prof. Devanand Shinde Hon’ble Vice-Chancellor & Chairman, BOSPC Dr. V. D. Nandavadekar Registrar Dr. P. T. Gaikwad Head, Department of Sports B.O.S.P.C. Experts Dr. S. S. Hunswadkar Shri. S. S. Mali Rajaram College, Kolhapur Arts & Commerce College, Kasegaon 1 OUR INSPIRATION Krida Maharshi Olympian Late Meghnath Bronze Medalist Nageshkar Late Khashaba D. Jadhav nd Birth: 02 Aug 1910 th Died on 21st Dec 1987. Birth: 15 Jan. 1926 Died on 14th Aug 1984. He was a leading renowned sports personality of Kolhapur. He not only He was an Indian wrestler, who won the remained an extra-ordinary player of first bronze medal for India since 1900 Cricket, Football, Hockey and Athletics, in the Individual sports - Wrestling in but he has dedicated his entire life for Men’s Freestyle Bantam weight the promotion of sports and physical category at the 1952 Summer Olympics culture in Kolhapur and in its vicinity. held in Helsinki. He has played a major role in He has received the Arjuna Award for developing the Sports Department and Wrestling in 2001. establishing major part of existing In 1955 he joined the police force as a sports infrastructure and facilities in Sub-Inspector and after serving for 27 our university. He took initiative to years he retired as Asst. Police introduce Compulsory P.E. Exam at 1st Commissioner. He has also won several year of the Degree Course in this competitions held within police University. -

Colours of Passion

COLOURS OF PASSION 70 110-208_LastingStrides0-208_LastingStrides 7700 111/9/071/9/07 111:04:011:04:01 AAMM Ng Liang Chiang. C. Kunalan. Chee Swee Lee. K. Jayamani. These are some of the names which readily come to mind whenever one talks about track and fi eld in Singapore. This is hardly surprising as they, in their hey days, were among the best athletes in the region. Whether it was Liang Chiang reigning supreme in the 110m hurdles at the 1951 Asian Games in New Delhi or Chee Swee Lee making her mark as a champion in the 400m at the 1974 Asian Games in Tehran, these athletes kept the Singapore fl ag fl ying high. Often they did this while also endearing themselves to fans. For example, Kunalan, who won three gold medals (100m, 200m and 4x400m relay) at the 1969 SEAP Games in Rangoon, was known as much for his likeable nature as his exploits on the track. On her part, Jayamani, who emerged as a star with gold medals in the 1977 SEA Games in Kuala Lumpur as well as the 1979 SEA Games in Jakarta, was unfailingly modest about her achievements. Behind the success of these athletes were dedicated coaches whose careers were so intimately linked to those of their athletes that their names were uttered in the same breath. For instance, mention C. Kunalan and Chee Swee Lee and one thinks almost immediately of coaches Tan Eng Yoon and Patrick Zehnder. Similarly, the feats of athletes like Jayamani and P. C. Suppiah were often associated with the hard work and dedication of their coach, Maurice Nicholas. -

Inventarisasi Tokoh Sejarah Dan Budaya Wilayah Kerja Balai Pelestarian Nilai Budaya Kepulauan Riau

INVENTARISASI TOKOH SEJARAH DAN BUDAYA WILAYAH KERJA BALAI PELESTARIAN NILAI BUDAYA KEPULAUAN RIAU Penulis: Anastasia Wiwik Swastiwi Sita Rohana Dedi Arman KEMENTERIAN PENDIDIKAN DAN KEBUDAYAAN DIREKTORAT JENDERAL KEBUDAYAAN BALAI PELESTARIAN NILAI BUDAYA KEPULAUAN RIAU 2018 INVENTARISASI TOKOH SEJARAH DAN BUDAYA WILAYAH KERJA BALAI PELESTARIAN NILAI BUDAYA KEPULAUAN RIAU Penulis: Anastasia Wiwik Swastiwi Sita Rohana Dedi Arman ISBN 978-602-51182-1-0 Editor : Sita Rohana Zulkifli Harto Desain Sampul dan Tata Letak : Ardiyansyah Nanda Darius Percetakan : CV. Genta advertising Jalan D.I. Panjaitan No. 4 Tanjungpinang Penerbit : Balai Pelestarian Nilai Budaya Kepulauan Riau Redaksi : Balai Pelestarian Nilai Budaya Kepulauan Riau Wilayah Kerja : Prov. Kepri, Riau, Jambi dan Kep. Babel Jalan Pramuka No. 7 Tanjungpinang Telp./Fax : 0771-22753 Pos-el : [email protected] Laman : kebudayaan.kemdikbud.go.id/bpnbkepri Cetakan Pertama : November 2018 Hak cipta dilindungi undang-undang Dilarang memperbanyak karya tulis dalam bentuk dan dengan cara apapun tanpa ijin tertulis dari penerbit SAMBUTAN KEPALA BALAI PELESTARIAN NILAI BUDAYA KEPULAUAN RIAU Syukur Alhamdulillah, senantiasa kita panjatkan ke khadirat Allah Yang Maha Kuasa; karena atas bimbingan dan ridho-Nyalah buku “INVENTARISASI TOKOH SEJARAH DAN BUDAYA” dapat disusun dan diterbitkan. Sejumlah fakta terkait INVENTARISASI TOKOH SEJARAH DAN BUDAYA yang dipaparkan dalam buku ini merupakan hasil kajian peneliti Balai Pelestarian Nilai Budaya (BPNB) KePulauan Riau. Berbagai upaya telah dilakukan untuk meningkatkan kualitas hasil kajian dimaksud sehingga hasil akhirnya dapat tersaji dengan lugas, akurat dan dapat dijadikan sumber bacaan atau referensi kesejarahan serta sumber informasi bagi penelitian lebih lanjut. Hal ini sejalan dengan salah satu tusi (tugas dan fungsi) BPNB antara lain melakukan kajian dan kemudian dikemas dalam bentuk buku serta bentuk terbitan lainnya dan disebarluaskan ke masyarakat, tidak saja untuk masyarakat lokasi kajian, akan tetapi disebarkan juga kepada masyarakat luas. -

IOC President Praises OCA

Official Newsletter of the Olympic Council of Asia Edition 52 - March 2021 WIN-WIN DOHA, RIYADH OCA GENERAL ASSEMBLY NAMES TWO ASIAN GAMES HOST CITIES Inside the OCA | OCA Games Update | NOC News | Women In Sport Contents Inside Sporting Asia Edition 52 – March 2021 3 President’s Message 9 4 – 9 Six pages of NOC News in Pictures 10 – 16 OCA Games Update 10 – 15 19th Asian Games Hangzhou 2022 16 Asian Youth Games Shantou 2021 12 17 – 24 39th OCA General Assembly Muscat 2020 17 OCA President’s welcome message 18 – 19 It’s a win-win situation 20 – 21 Muscat Photo Gallery 23 22 OCA Order of Merit/AYG Tashkent 2025 23 IOC President praises OCA 24 General Assembly Notebook 25 – 27 Inside the OCA 28 28 – 31 Women in Sport 32 – 33 Road to Tokyo 34 – 35 News in Brief 36 – 37 Obituary 38 – 39 OCA Sports Diary 32 40 Hangzhou 2022 OCA Sponsors’ Club * Page 02 President’s Message OCA WILL EMERGE STRONGER FROM PANDEMIC PROBLEMS Sporting Asia is the official newsletter of the Olympic Council of Asia, published quarterly. Executive Editor / Director General Husain Al-Musallam [email protected] Director, Int’l & NOC Relations Vinod Tiwari [email protected] Director, Asian Games Department Haider A. Farman [email protected] Editor IT Director t was very disappointing to postpone two This will make it a busy year for our NOCs, Amer Elalami I Jeremy Walker [email protected]@ocasia.org of our OCA games in quick succession. with the Beijing Winter Olympics in Febru- ary, AIMAG 6 in March and our 19th Asian Executive Secretary The 6th Asian Beach Games in Sanya, China Games in Hangzhou, China in September. -

40 an ANALYTICAL STUDY of 1St ASIAN GAMES HELD IN

I J R S S I S, Vol. II, Issue (4), Nov 2015: 40-43 ISSN 2347 – 8209 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCHES IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND INFORMATION STUDIES © VISHWASHANTI MULTIPURPOSE SOCIETY (Global Peace Multipurpose Society) R. No. MH-659/13(N) www.vmsindia.org AN ANALYTICAL STUDY OF 1 st ASIAN GAMES HELD IN INDIA DURING 1951 Arun Motghare Dr. Arun Motghare Mahavidyalaya, Kondha-Kosra, Tal. Pauni, Dist. Bhandara [email protected] Abstract: 4th March 1951 is the day to be written in the golden letters not only for Indian sports history but for the history of Asian games. The first president of Indian republic Dr. Rajendra Prasad inaugurated the first Asian games in the newly constructed National stadium at New Delhi in the great enthusiasm. 600 male female players of the 11countries in Asia saluted it. The researcher has studied the following tools for his research, International game and India (book), Asian games 1951, Asian Games; Statistical Digest. In first Asian games India was on 2 nd number. Japan got the first place. India got 15 Gold medals, 16 silver medals and 21 Bronze medals in the game. Iran got the third place. 24 players from Japan Iran India and Bramhadesh participated in it and Japanese player in 5 hours 22 minute 226 seconds. 40 players participated in it and Iran players outplayed all in this event. 6 nations participated in this. In the finals India beat Iran team in a thrilling match by 1 goal. Five nations participated in this. Games were played in league system. Philippines team scored the maximum points and was the winner. -

Major Dhyanchand National Stadium, New Delhi, India

REFERENCE Major Dhyanchand National Stadium, New Delhi, India Application Field Product systems used / Size . Water Vapour Permeable Water Vapour Permeable Flooring Flooring Car Park Area Stadium Tiers Structure Type Products: Epoxy BS 2000, Epoxy BS 3000 . Stadiums/Arenas/Sports Venues Scope of Work Client Brief description The stadium tiers were coated by Central Public Works Department Major Dhyanchand National Stadium using Remmers Epoxy BS (CPWD) is a field hockey stadium at New 2000/Epoxy BS 3000 system Delhi, India. It originally held 25,000 during the reconstruction work Specifier people. It is named after former done for the 2010 Hockey World Indian field hockey player, Dhyan CPWD Cup. Also the car park area of the Chand. It served as the venue for Installer the 1st Asian Games in 1951. The stadium was done with Remmers stadium was built in 1933 as a Epoxy BS 2000/Epoxy BS 3000 Startech Flooring & Chemical multipurpose stadium and named system before the advent of the Services, Gurgaon the Irwin Amphitheatre. It was Common Wealth Games 2010. designed by Anthony S. DeMillo. It Completion was renamed National Stadium before the 1951 Asian Games, 2009-2010 Dhyan Chand's name was added in 2002. The Dhyan Chand Stadium was the host venue for the 2010 Men's Hockey World Cup. It was also the hockey venue of the 2010 Commonwealth Games. The stadium underwent a major reconstruction project before the Hockey World Cup 2010. On 24 January 2010 it became the first venue for the 2010 Commonwealth Games to be unveiled. The stands, which were earthen embankments, were demolished and a new rectangular seating bowl was constructed in its place. -

Football Link

SPECIAL EDITION FEATURE - INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL 2012 THE FOOTBALL LINK IN THE PIPELINE | 25 /// INTERNATIONAL CLUBS | 5 /// SOCIAL INITIATIVES | 9 TRUE TO THE PLAYER. TRUE TO THE GAME. This magazine aims to highlight the opinions and interests of football lovers across India. This special edition covers TheFootballLink International Festival 2012 held at the Thyagaraj Stadium, New Delhi from the 6th to 13th of October. By spreading the message of football, TheFootballLink provides a platform for football enthusiasts to connect with each other and organize various initiatives in football; to support, participate and contribute to the growth of the game. 03 CONTENTS 05 PRELUDE 01 LEGACY OF INDIAN FOOTBALL An insight into the glorious past of Indian football FEATURE 08 05 INTERNATIONAL CLUB PARTNERS AC Milan Junior Camp, Italy & Manchester City Football Club, England 11 SPONSORS/PARTNERS An overview of the contributors to the International Festival 2012 13 MEDIA COVERAGE The largest football festival ever organized in 17 India 15 TESTIMONIALS International Coaches, Scouts & Agents sharing their experiences 17 CYCLE OF FOOTBALL Business, Social & Performance aspects of Football 23 INSIGHT 21 pAST INITIATIVES Initiatives organized by TheFootballLink 23 BOOK PREVIEW Stop Dribbling, Pass Now! 25 IN THE pipELINE Find out what the future holds in store for TFL 27 SPOTLIGHT 27 CAN FOOTBALL A campaign revolving around 6 questions to highlight ways in which football can benefit our country Legacy of Indian Football ootball started its journey in India when IFA-Shield Trophy. The AIFF got affiliation Fthe British rulers brought it with them from the international governing body and in no time, it became popular among for Football, FIFA in 1948 and it was also the masses. -

Jul–Sep 2015

Vol. 11 Issue biblioasia02 2015 JUL–SEP 02 / The Singapore Dream 04 / Sporting Legends 12 / Living the Singapore Story 20 / Trailblazers of Dance 26 / The Mad Chinaman 32 / Father of Malay Journalism Pushing Boundaries BiblioAsia Director’s Note Editorial & CONTENTS Vol. 11 / Issue 02 Jul–Sep 2015 Production Singapore’s stellar performance at the 28th Southeast Asia (SEA) Games is proof that Managing Editor our athletes have the guts and gumption to push the boundaries and achieve sporting Francis Dorai excellence. Singapore’s haul of 259 medals – 84 gold, 73 silver and 102 bronze – which put us in second place at the medal standings behind Thailand – is no mean feat for a tiny Editors OPINION nation whose athletes had to compete against the region’s elite. Singapore delivered its Veronica Chee Stephanie Pee best showing since the 1993 Games – when it won 164 medals – and in the process broke more than 100 SEA Games as well as many national and personal records. Editorial Support This issue of BiblioAsia, aptly themed “Pushing Boundaries”, celebrates the achieve- Masamah Ahmad ments and personal stories of Singaporeans – athletes, entertainers, dancers, civil serv- ants, the ordinary man in the street – especially those who defied the odds and overcame Design and Print adversity to fulfil their dreams. Oxygen Studio Designs Pte Ltd Former journalist Chua Chong Jin relives the glory days of some of Singapore’s Contributors 02 iconic names in sports, such as weightlifter Tan Howe Liang who won a silver at the 1960 Chua Chong Jin, Seizing the Singapore Dream Rome Olympics; high-jumper Lloyd Valberg, the first athlete to represent Singapore at the Han Foo Kwang, Parag Khanna, Olympics in 1948; and sprinter C. -

Sports Newsletter

APEC Sports Newsletter 03 October 2017 ISSUE Women and Sports Foreword / 02 APEC Economies' Policies / 03 -Summary Report: 2017 APEC International Conference on Women and Sport / 03 - Policy and Best Practice Sharing from Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Philippine, Papua New Guinea, Chinese Taipei and Vietnam / 07 Perspectives on Regional Sports Issues / 39 -Summary of 2017 Taipei Summer Universiade / 39 -Activities of the "Host Town Initiative" and Introduction of "beyond2020" Program / 42 -Singapore's Public-Private Partnerships in Sports: A Dream, Come True / 45 -Insights into the Asian Games / 50 -Thailand to Host 2017 Sport Accord Convention / 56 ASPN Related Events / 59 APEC Economies' Perspectives on ASPN Related Foreword Policies Regional Sports Issues Events Foreword This April and July, ASPN has released two editions of the APEC Sports Newsletter to explore the education and career planning of youth athletes and to share best practices of youth entrepreneurship in all economies. In recent years, as women awareness has been gaining momentum across the globe, cultivation of personal inner value and professional capability has been receiving much focus. Echoing the trend, Chinese Taipei released its official "Women's Sports Participation Advocacy White Paper" earlier this year. This is the high time that we have deep discussion on issues regarding women in sports. As mentioned in the 2016 APEC Leaders' Declarations, "We recognize women's vital contribution to economic and social development and we commit to strengthen our efforts to support the mainstreaming of gender equality and women's empowerment across APEC's work, to ensure that women enjoy equal access to quality education and economic resources." The value of sports lies not only in biological health maintenance, but also in its strength in promoting confidence, communication, coordination capabilities and cultivating self-esteem and leadership, by way of sports participation. -

Japanese Women and Sport: Beyond Baseball and Sumo

Kietlinski, Robin. "Notes." Japanese Women and Sport: Beyond Baseball and Sumo. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2011. 147–174. Globalizing Sport Studies. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 24 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781849666701.0010>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 24 September 2021, 20:54 UTC. Copyright © Robin Kietlinski 2011. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. Notes Chapter 1 Introduction: Why women’s sport? Why Japan? 1 Image can be seen on the Japan Post website (Japanese only): http://www.post. japanpost.jp/kitte_hagaki/stamp/design_stamp/2000/image/20c_des_5l.jpg [accessed 4 August 2011]. 2 See French (2003). 3 Another telling fi gure is that in 2004 there were ten per cent more female than male delegates representing Japan at the Summer Olympics in Athens. Japan was one of the very few nations at these Olympics with more female than male athletes. 4 Fujita 1968: 93. 5 Cha 2009: 25. 6 For example, Korean athletes in occupied Korea in the 1920s formed athletic clubs that were strongly associated with independence movements, as sport was one of the few ways that Koreans were permitted by the Japanese to congregate in groups. Sporting bouts between occupied Koreans and their Japanese colonizers came to be seen as symbolic fi ghts for Korea’s independence from Japan (Cha 2009: 25). 7 The New York Times , 3 August 1928. 8 Books written in English