Memoirs of the Memorable

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JUNE 1962 The

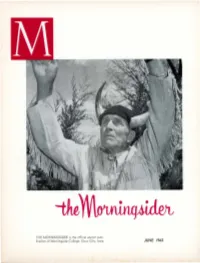

THE MORNINGSIDERis the official alumni publ- ication of Morningside College, Sioux City, Iowa JUNE 1962 The President's Pen The North Iowa Annual Conference has just closed its 106th session. On the Cover Probably the most significant action of the Conference related to Morningside and Cornell. Ray Toothaker '03, as Medicine Man Greathealer, The Conference approved the plans for the pro raises his arms in supplication as he intones the chant. posed Conference-wide campaign, which will be conducted in 1963 for the amount of $1,500,000.00, "O Wakonda, Great Spirit of the Sioux, brood to be divided equally between the two colleges over this our annual council." and used by them in capital, or building programs. For 41 years, Mr. Toothaker lhas played the part of Greathealer in the ceremony initiating seniors into The Henry Meyer & Associates firm was em the "Tribe of the Sioux". ployed to direct the campaign. The cover picture was taken in one of the gardens Our own alumnus, Eddie McCracken, who is at Friendship Haven in Fort Dodge, Iowa, where Ray co-chairman of the committee directing the cam resides. Long a highly esteemed nurseryman in Sioux paign, was present at the Conference during the City, he laid out the gardens at Friendship Haven, first three critical days and did much in his work plans the arrangements and supervises their care. among laymen and ministers to assure their con His knowledge and love of trees, shrubs and flowers fidence in the program. He presented the official seems unlimited. It is a high privilege to walk in a statement to the Conference for action and spoke garden with him. -

Esther (Seymour) Atu,Ooa

The Descendants of John G-randerson and Agnes All en (Pulliam,) Se1f11JJ)ur also A Sho-rt Htstory of James Pull tam by Esther (Seymour) Atu,ooa Genealogtcal. Records Commtttee Governor Bradford Chapter Da,u,ghters of Amertcan Bevolutton Danvtlle, Illtnots 1959 - 1960 Mrs. Charles M. Johnson - State Regent Mrs. Richard Thom,pson Jr. - State Chatrman of GenealogtcaJ Records 11rs. Jv!erle s. Randolph - Regent of Governor Bradford Chapter 14rs. Louis Carl Ztllman)Co-Chairmen of Genealogical. Records Corruntttee Mrs. Charles G. Atwood ) .,;.page 1- The Descendants of John Granderson and Agnes Allen (PuJ.liat~) SeymJJur also A Short History of JOJTJSS ...Pall tarn, '1'he beginntng of this genealogy oos compiled by Mrs. Emrra Dora (Mansfield) Lowdermtlk, a great granddaughter of John Granderson ar~ Agnes All en ( Pu.11 iam) SeymJJur.. After the death of }!rs. Lowdermtlk, Hrs. Grace (Roberts) Davenport added, to the recordso With t'he help of vartous JCJ!l,tly heads over a pertod of mcre than three years, I haDe collected and arrari;Jed, the bulk of the data as tt appears in this booklet. Mach credtt ts due 11"'-rs. Guy Martin of Waverly, Illtnots, for long hours spent tn copytn.g record,s for me in. 1°11:organ Oounty Cou,rthou,se 1 and for ,~.,. 1.vorlt in catalogu,tn,g many old country cemetertes where ouP ktn are buried. Esther (SeymDur) Atluooa Typi!IIJ - Courtesy of Charles G. Atwood a,,-.d sec-reta;ry - .l'efrs e El ea?1fJ7' Ann aox. Our earl1est Pulltam ancestora C(]lTl,e from,En,gland to vtrsgtnta, before the middle of the sel)enteenth century. -

Mundella Papers Scope

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 6 - 9, MS 22 Title: Mundella Papers Scope: The correspondence and other papers of Anthony John Mundella, Liberal M.P. for Sheffield, including other related correspondence, 1861 to 1932. Dates: 1861-1932 (also Leader Family correspondence 1848-1890) Level: Fonds Extent: 23 boxes Name of creator: Anthony John Mundella Administrative / biographical history: The content of the papers is mainly political, and consists largely of the correspondence of Mundella, a prominent Liberal M.P. of the later 19th century who attained Cabinet rank. Also included in the collection are letters, not involving Mundella, of the family of Robert Leader, acquired by Mundella’s daughter Maria Theresa who intended to write a biography of her father, and transcriptions by Maria Theresa of correspondence between Mundella and Robert Leader, John Daniel Leader and another Sheffield Liberal M.P., Henry Joseph Wilson. The collection does not include any of the business archives of Hine and Mundella. Anthony John Mundella (1825-1897) was born in Leicester of an Italian father and an English mother. After education at a National School he entered the hosiery trade, ultimately becoming a partner in the firm of Hine and Mundella of Nottingham. He became active in the political life of Nottingham, and after giving a series of public lectures in Sheffield was invited to contest the seat in the General Election of 1868. Mundella was Liberal M.P. for Sheffield from 1868 to 1885, and for the Brightside division of the Borough from November 1885 to his death in 1897. -

The Development of Provided Schooling for Working Class Children

THE DEVELOPMENT OF PROVIDED SCHOOLING FOR WORKING CIASS CHILDREN IN BIRMINGHAM 1781-1851 Michael Brian Frost Submitted for the degree of Laster of Letters School of History, Faculty of Arts, University of Birmingham, 1978. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. SYNOPSIS This thesis considers the development of 'provided 1 schooling for working class children in Birmingham between 1781 and 1851. The opening chapters critically examine the available statistical evidence for schooling provision in this period, suggesting how the standard statistical information may be augmented, and then presenting a detailed chronology of schooling provision and use. The third chapter is a detailed survey of the men who were controlling and organizing schooling during the period in question. This survey has been made in order that a more informed examination of the trends in schooling shown by the chronology may be attempted. The period 1781-1851 is divided into three roughly equal periods, each of which parallels a major initiative in working class schooling; 1781-1804 and the growth of Sunday schools, 1805-1828 and the development of mass day schooling through monitorial schools, and 1829- 1851 and the major expansion of day schooling. -

Founder and First Organising Secretary of the Workers' Educational Association; 1893-1952, N.D

British Library: Western Manuscripts MANSBRIDGE PAPERS Correspondence and papers of Albert Mansbridge (b.1876, d.1952), founder and first organising secretary of the Workers' Educational Association; 1893-1952, n.d. Partly copies. Partly... (1893-1952) (Add MS 65195-65368) Table of Contents MANSBRIDGE PAPERS Correspondence and papers of Albert Mansbridge (b.1876, d.1952), founder and first organising secretary of the Workers' Educational Association; 1893–1952, n.d. Partly copies. Partly... (1893–1952) Key Details........................................................................................................................................ 1 Provenance........................................................................................................................................ 1 Add MS 65195–65251 A. PAPERS OF INSTITUTIONS, ORGANISATIONS AND COMMITTEES. ([1903–196 2 Add MS 65252–65263 B. SPECIAL CORRESPONDENCE. 65252–65263. MANSBRIDGE PAPERS. Vols. LVIII–LXIX. Letters from (mostly prominent)........................................................................................ 33 Add MS 65264–65287 C. GENERAL CORRESPONDENCE. 65264–65287. MANSBRIDGE PAPERS. Vols. LXX–XCIII. General correspondence; 1894–1952,................................................................................. 56 Add MS 65288–65303 D. FAMILY PAPERS. ([1902–1955]).................................................................... 65 Add MS 65304–65362 E. SCRAPBOOKS, NOTEBOOKS AND COLLECTIONS RELATING TO PUBLICATIONS AND LECTURES, ETC. ([1894–1955])......................................................................................................... -

Stanley Families.Pdf

FAMILY ENTER All DATA IN THIS ORDER: NAMES: WATSON, John Henry Vv GROUP DATES: 14 Apr 1794 PI ACES: Shoron. Windir, Vt ^ RECORD To indicate that a child is an ancestor of the family representative, place an "X" behind the number pertaining to th^child. 1 0) 10$ •ni" 2*9 SB o 112 2 C H- 5«1 s ^ >C® 22* c ">3:2 3 »2 ®- -=5 • a D n PJ 2Si o (A > a w s® c T 5> 2 S» m ®2 ^ « JO - 2 ? O D o e\ (A b *5- >N > Z > 2 I <s Z n E "" 0 '0 a h 'A s V ??g is Q N r* 5 N ^ c < N I 0 2 5 b Z a 5^ > - Z = V cn s h- is > , > c> I; 21 OC HCA in ZD PICA Pl> a az D (ri i: : :h > ' ' Z th 1 i > N I IL nv < $ s zl 0 m Z 2 lO 0\ u- FAMILY ENTER ALL DATA IN THIS^RDER: V, ^ ^NAMES: WATSON. John Henry GROUP DATES: 14 Apr 179^ y ^ ^ ^lACES: Shoron. Windsr, Vl ^ RECORD To indicate that a child it an ancestor of the family representative, place an "X" behind the number pertaining to that child. XO^ o» o n 5 i "n ■r\: >1 X ms " CH- >!l >c® a o (on -tm =1 o m PJ znl T® (A _ *ri > a w i® c 7 "(ri m 2 ®z O a - N 2 ? O 0 (A > 1 (A V. z ~ n i V n I X "N ei' > s N a ds <$> 2 Is r> 9D H. -

DISPENSATION and ECONOMY in the Law Governing the Church Of

DISPENSATION AND ECONOMY in the law governing the Church of England William Adam Dissertation submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Wales Cardiff Law School 2009 UMI Number: U585252 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U585252 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 CONTENTS SUMMARY............................................................................................................................................................IV ACKNOWLEDGMENTS..................................................................................................................................VI ABBREVIATIONS............................................................................................................................................VII TABLE OF STATUTES AND MEASURES............................................................................................ VIII U K A c t s o f P a r l i a m e n -

Holders of Ministerial Office in the Conservative Governments 1979-1997

Holders of Ministerial Office in the Conservative Governments 1979-1997 Parliamentary Information List Standard Note: SN/PC/04657 Last updated: 11 March 2008 Author: Department of Information Services All efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy of this data. Nevertheless the complexity of Ministerial appointments, changes in the machinery of government and the very large number of Ministerial changes between 1979 and 1997 mean that there may be some omissions from this list. Where an individual was a Minister at the time of the May 1997 general election the end of his/her term of office has been given as 2 May. Finally, where possible the exact dates of service have been given although when this information was unavailable only the month is given. The Parliamentary Information List series covers various topics relating to Parliament; they include Bills, Committees, Constitution, Debates, Divisions, The House of Commons, Parliament and procedure. Also available: Research papers – impartial briefings on major bills and other topics of public and parliamentary concern, available as printed documents and on the Intranet and Internet. Standard notes – a selection of less formal briefings, often produced in response to frequently asked questions, are accessible via the Internet. Guides to Parliament – The House of Commons Information Office answers enquiries on the work, history and membership of the House of Commons. It also produces a range of publications about the House which are available for free in hard copy on request Education web site – a web site for children and schools with information and activities about Parliament. Any comments or corrections to the lists would be gratefully received and should be sent to: Parliamentary Information Lists Editor, Parliament & Constitution Centre, House of Commons, London SW1A OAA. -

List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007

Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007 A - J Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 A complete listing of all Fellows and Foreign Members since the foundation of the Society A - J July 2007 List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 The list contains the name, dates of birth and death (where known), membership type and date of election for all Fellows of the Royal Society since 1660, including the most recently elected Fellows (details correct at July 2007) and provides a quick reference to around 8,000 Fellows. It is produced from the Sackler Archive Resource, a biographical database of Fellows of the Royal Society since its foundation in 1660. Generously funded by Dr Raymond R Sackler, Hon KBE, and Mrs Beverly Sackler, the Resource offers access to information on all Fellows of the Royal Society since the seventeenth century, from key characters in the evolution of science to fascinating lesser- known figures. In addition to the information presented in this list, records include details of a Fellow’s education, career, participation in the Royal Society and membership of other societies. Citations and proposers have been transcribed from election certificates and added to the online archive catalogue and digital images of the certificates have been attached to the catalogue records. This list is also available in electronic form via the Library pages of the Royal Society web site: www.royalsoc.ac.uk/library Contributions of biographical details on any Fellow would be most welcome. -

Rutland Record 29 (2009)

RR29 Cover:Layout 1 22/10/2009 16:22 Page 1 Rutland Record 29 Journal of the Rutland Local History & Record Society RR29 Cover:Layout 1 22/10/2009 16:22 Page 2 Rutland Local History & Record Society The Society is formed from the union in June 1991 of the Rutland Local History Society, founded in the 1930s, and the Rutland Record Society, founded in 1979. In May 1993, the Rutland Field Research Group for Archaeology & History, founded in 1971, also amalgamated with the Society. The Society is a Registered Charity, and its aim is the advancement of the education of the public in all aspects of the history of the ancient County of Rutland and its immediate area. Registered Charity No. 700723 PRESIDENT Edward Baines CHAIRMAN Dr Michael Tillbrook VICE-CHAIRMAN Robert Ovens HONORARY SECRETARY c/o Rutland County Museum, Oakham, Rutland HONORARY TREASURER Dr Ian Ryder HONORARY MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY Mrs Enid Clinton HONORARY EDITOR Tim Clough HONORARY ARCHIVIST Dr Margaret Bonney EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE The Officers of the Society and the following elected members: Mrs Audrey Buxton, Mrs Elizabeth Bryan, Rosemary Canadine, David Carlin, Robert Clayton, Hilary Crowden, Dr Peter Diplock, Mrs Kate Don, Michael Frisby (webmaster), Charles Haworth, Mrs Jill Kimber, Chris Wilson EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Edward Baines, Tim Clough (convener), Dr Peter Diplock (assistant editor), Robin Jenkins, Robert Ovens, Professor Alan Rogers (academic adviser), Dr Ian Ryder, Dr M Tillbrook ARCHAEOLOGICAL GROUP Mrs Kate Don (convener) HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT GROUP Mr D Carlin (convener) HONORARY MEMBERS Sqn Ldr A W Adams, Mrs B Finch, Mrs S Howlett, P N Lane, B Waites Enquiries relating to the Society’s activities, such as membership, editorial matters, historic buildings, archaeology, or programme of events, should be addressed to the appropriate Officer of the Society. -

Descendants of Felix Seymour

Descendants of Felix Seymour Prepared by: Thomas N. Oatney Table of Contents Descendants of Felix Seymour 1 First Generation 1 Second Generation 1 Third Generation 1 Fourth Generation 2 Fifth Generation 7 Sixth Generation 25 Seventh Generation 56 Eighth Generation 91 Ninth Generation 113 Tenth Generation 122 11th Generation 127 Name Index 128 Produced by: Thomas Oatney tom @ oatney . org : 24 Mar 2021 Descendants of Felix Seymour First Generation 1. Felix Seymour was born in 1725 in England and died in Feb 1798 in Hampshire County, VA at age 73. Felix married Margaret Renick in 1752. Margaret was born in 1734 in Lancaster County, PA and died in 1798 in Hardy County, (W) VA at age 64. Children from this marriage were: 2 M i. John Seymour was born on 7 May 1754 in Hardy County, (W)VA and died in 1755 in VA at age 1. 3 M ii. Richard Seymour was born on 25 Aug 1755 in Hardy County, (W)VA and died in 1811 in (W)VA at age 56. + 4 M iii. Thomas Seymour was born on 28 Jan 1756 in Hardy County, (W)VA, died on 16 Apr 1831 in Licking County, OH at age 75, and was buried in Cedar Hill Cemetery, Newark, Licking County, OH. 5 M iv. Abel Renick Seymour was born on 5 May 1760 in Hardy County, (W)VA and died in 1823 in Hardy County, (W)VA at age 63. 6 M v. George Seymour was born on 11 Aug 1762 in Hardy County, (W)VA, died on 5 May 1839 in OH at age 76, and was buried in Welton Cemetery, Groveport, Franklin County, OH. -

Acq. by Mar. Early 18Th C., Built Mid-18Th C., Sold 1914) Estates: 4528 (I) 2673

742 List of Parliamentary Families Seat: Prehen, Londonderry (acq. by mar. early 18th c., built mid-18th c., sold 1914) Estates: 4528 (I) 2673 Knox [Gore] Origins: Descended from an older brother of the ancestor of the Earls of Ranfurly. Mary Gore, heiress of Belleek Manor (descended from a brother of the 1 Earl of Arran, see Gore), married Francis Knox of Rappa. One of their sons succeeded to Rappa and another took the additional name Gore and was seated at Belleek. 1. Francis Knox – {Philipstown 1797-1800} 2. James Knox-Gore – {Taghmon 1797-1800} Seats: Rappa Castle, Mayo (Knox acq. mar. Gore heiress 1761, family departed 1920s, part demolished 1937, ruin); Moyne Abbey, Mayo (medieval, burned 1590, partly restored, acq. mid-17th c., now a ruin); Belleek Manor (Abbey, Castle), Mayo (rebuilt 1831, sold c. 1942, hotel) Estates: Bateman 30592 (I) 11082 and at Rappa 10722 (I) 2788 (five younger sons given 1,128 acres worth £408 pa each in mid-19th c.) Title: Baronet 1868-90 1 Ld Lt 19th Knox Origins: Cadet of the Rappa line. 1. John Knox – {Dongeal 1761-68 Castlebar 1768-74} 2. Lawrence Knox – Sligo 1868-69 Seat: Mount Falcon, Mayo (acq. 19th c., built 1876, sold 20th c., hotel) Estates: Bateman 5589 (I) 2246. Still owned 93 acres in 2001. LA TOUCHE IRELAND Origins: Huguenot refugees who came from Amsterdam to Ireland with William III’s army. One fought at the Boyne. Sheriff 1797. They operated a poplin factory in Dublin from 1694 and then became bankers (1712) and country gentlemen simultaneously in the 18th and 19th centuries.