Latvia and the USA: from Captive Nation to Strategic Partner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LATVIA in REVIEW July 26 – August 1, 2011 Issue 30

LATVIA IN REVIEW July 26 – August 1, 2011 Issue 30 CONTENTS Government Latvia's Civic Union and New Era Parties Vote to Participate in Foundation of Unity Party About 1,700 people Have Expressed Wish to Join Latvia's Newly-Founded ZRP Party President Bērziņš to Draft Legislation Defining Criteria for Selection of Ministers Parties Represented in Current Parliament Promise Clarity about Candidates This Week Procedure Established for President’s Convening of Saeima Meetings Economics Bank of Latvia Economist: Retail Posts a Rapid Rise in June Latvian Unemployment Down to 12.3% Fourteen Latvian Banks Report Growth of Deposits in First Half of 2011 European Commission Approves Cohesion Fund Development Project for Rīga Airport Private Investments Could Help in Developing Rīga and Jūrmala as Tourist Destinations Foreign Affairs Latvian State Secretary Participates in Informal Meeting of Ministers for European Affairs Cabinet Approves Latvia’s Initial Negotiating Position Over EU 2014-2020 Multiannual Budget President Bērziņš Presents Letters of Accreditation to New Latvian Ambassador to Spain Society Ministry of Culture Announces Idea Competition for New Creative Quarter in Rīga Unique Exhibit of Sand Sculptures Continues on AB Dambis in Rīga Rīga’s 810 Anniversary to Be Celebrated in August with Events Throughout the Latvian Capital Labadaba 2011 Festival, in the Līgatne District, Showcases the Best of Latvian Music Latvian National Opera Features Special Summer Calendar of Performances in August Articles of Interest Economist: “Same Old Saeima?” Financial Times: “Crucial Times for Investors in Latvia” L’Express: “La Lettonie lutte difficilement contre la corruption” Economist: “Two Just Men: Two Sober Men Try to Calm Latvia’s Febrile Politics” Dezeen magazine: “House in Mārupe by Open AD” Government Latvia's Civic Union, New Era Parties Vote to Participate in Foundation of Unity Party At a party congress on July 30, Latvia's Civic Union party voted to participate in the foundation of the Unity party, Civic Union reported in a statement on its website. -

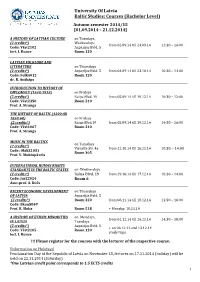

University of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level)

University Of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level) Autumn semester 2014/15 [01.09.2014 – 21.12.2014] A HISTORY OF LATVIAN CULTURE on Tuesdays, (2 credits*) Wednesdays from 02.09.14 till 24.09.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst2102 Azpazijas Bvld. 5 lect. I. Runce Room 120 LATVIAN FOLKLORE AND LITERATURE on Thursdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. 5 from 04.09.14 till 23.10.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: Folk4012 Room 120 dr. R. Auškāps INTRODUCTION TO HISTORY OF DIPLOMACY (1648-1918) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 10:30 – 12:00 Code: Vēst2350 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga THE HISTORY OF BALTIC (1200 till 1850-60) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd.19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 14:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst1067 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga MUSIC IN THE BALTICS on Tuesdays (2 credits*) Visvalža Str. 4a from 21.10.14 till 16.12.14 10:30. – 14:00 Code : MākZ1031 Room 305 Prof. V. Muktupāvels INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS STANDARTS IN THE BALTIC STATES on Wednesdays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 29.10.14 till 17.12.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: JurZ2024 Room 6 Asoc.prof. A. Kučs RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT on Thursdays OF LATVIA Azpazijas Bvld. 5 (2 credits*) Room 320 from 06.11.14 till 18.12.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Ekon5069 Prof. B. Sloka Room 518 + Monday, 10.11.14 A HISTORY OF ETHNIC MINORITIES on Mondays, from 01.12.14 till 16.12.14 14:30 – 18:00 IN LATVIA Tuesdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. -

Helsinki Watch Committees in the Soviet Republics: Implications For

FINAL REPORT T O NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARC H TITLE : HELSINKI WATCH COMMITTEES IN THE SOVIET REPUBLICS : IMPLICATIONS FOR THE SOVIET NATIONALITY QUESTIO N AUTHORS : Yaroslav Bilinsky Tönu Parming CONTRACTOR : University of Delawar e PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATORS : Yaroslav Bilinsky, Project Director an d Co-Principal Investigato r Tönu Parming, Co-Principal Investigato r COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 621- 9 The work leading to this report was supported in whole or in part fro m funds provided by the National Council for Soviet and East European Research . NOTICE OF INTENTION TO APPLY FOR COPYRIGH T This work has been requested for manuscrip t review for publication . It is not to be quote d without express written permission by the authors , who hereby reserve all the rights herein . Th e contractual exception to this is as follows : The [US] Government will have th e right to publish or release Fina l Reports, but only in same forma t in which such Final Reports ar e delivered to it by the Council . Th e Government will not have the righ t to authorize others to publish suc h Final Reports without the consent o f the authors, and the individua l researchers will have the right t o apply for and obtain copyright o n any work products which may b e derived from work funded by th e Council under this Contract . ii EXEC 1 Overall Executive Summary HELSINKI WATCH COMMITTEES IN THE SOVIET REPUBLICS : IMPLICATIONS FOR THE SOVIET NATIONALITY QUESTION by Yaroslav Bilinsky, University of Delawar e d Tönu Parming, University of Marylan August 1, 1975, after more than two years of intensive negotiations, 35 Head s of Governments--President Ford of the United States, Prime Minister Trudeau of Canada , Secretary-General Brezhnev of the USSR, and the Chief Executives of 32 othe r European States--signed the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperatio n in Europe (CSCE) . -

Read More on Baltic International

INNOVATIONS TEAM aimed at innovations EXCELLENT OF EXPERTS and excellence SERVICE 25 REASONS WE ARE PROUD OF know-how truly individual high and experience quality service FAMILY BANK a bank owned SUPPORT by family TRUST TO STARTUPS and devoted we appreciate we believe in future to families trust of clients of start-ups and employees ESG JOY OF 25YEAR Environmental. WORKING EXPERIENCE GOOD Social. TOGETHER Let’s celebrate RESOURCE BASE Government. we love to work 25th anniversary strong resource base together! on May 3 and OUR WAY and sound development entire year 2018! OF SUCCESS, CHALLENGES RELIABILITY SUSTAINABILITY we are reliable, AND gold level open and honest in Sustainability index long-term business VICTORIES partner PATRONS SUPPORT OF CULTURE TO LITERATURE WINNERS SUCCESSION AND ART we believe in power #WinnersBorninLatvia we believe in importance care for succession of literature of families and succession of national values SMART EXPERTISE INVESTMENTS helps to find OFFICE we invest with our clients the best solutions IN THE HEART in a smart way OF OLD RIGA for our customers working in the rhythm of the heartbeats of Riga RESPECTFUL SHAREHOLDERS we trust our shareholders, RESPONSIBILITY STRONG TEAM GREEN SPORTIVE AND COMPETITIVE and they trust us responsible for wealth good team of energetic THINKING ENTHUSIASTIC PRODUCTS management of our clients and loyal experts care for nature we enjoy working wide spectrum and ourselves and sporting together and competitive features Business review 2017 CONTENTS 3 Valeri Belokon, Chairman of Supervisory Board 5 Viktor Bolbat, Deputy Chairman of Management Board 7 Bank financial results review 10 Overall review of Latvian economy 13 Developments on global financial markets 15 Baltic International Bank: support to the society, environment, and the world 19 Baltic International Bank — 25! VALERI BELOKON e Chairperson of the Supervisory Board of Baltic International Bank Whatever you do in life, do it with all your heart. -

Conde, Jonathan (2018) an Examination of Lithuania's Partisan War Versus the Soviet Union and Attempts to Resist Sovietisation

Conde, Jonathan (2018) An Examination of Lithuania’s Partisan War Versus the Soviet Union and Attempts to Resist Sovietisation. Masters thesis, York St John University. Downloaded from: http://ray.yorksj.ac.uk/id/eprint/3522/ Research at York St John (RaY) is an institutional repository. It supports the principles of open access by making the research outputs of the University available in digital form. Copyright of the items stored in RaY reside with the authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full text items free of charge, and may download a copy for private study or non-commercial research. For further reuse terms, see licence terms governing individual outputs. Institutional Repository Policy Statement RaY Research at the University of York St John For more information please contact RaY at [email protected] An Examination of Lithuania’s Partisan War Versus the Soviet Union and Attempts to Resist Sovietisation. Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Research MA History at York St John University School of Humanities, Religion & Philosophy by Jonathan William Conde Student Number: 090002177 April 2018 I confirm that the work submitted is my own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the works of others. This copy has been submitted on the understanding that it is copyright material. Any reuse must comply with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and any licence under which this copy is released. @2018 York St John University and Jonathan William Conde The right of Jonathan William Conde to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 Acknowledgments My gratitude for assisting with this project must go to my wife, her parents, wider family, and friends in Lithuania, and all the people of interest who I interviewed between the autumn of 2014 and winter 2017. -

Latvia the Claim for Independence Leva JÄ Kobsone* * Desk Officer

Latvia The Claim for Independence leva J�kobsone* The legal basis for de facto renewal of sovereignty of the Republic of Latvia was laid on 4 May 1990, one year before the collapse of the Soviet Union. On this date the Declaration of the Supreme Soviet of the Latvian SSR On the Renewal of the Independence of the Republic of Latvia proclaimed the renewal of independence of the State establishing a transition period for the restoration of de facto independence. The Declaration stated that the incorporation of the Republic of Latvia in the Soviet Union was illegal with respect to general principles of international law and that the Republic of Latvia continued to exist de jure as the subject of international law during the occupation by the Soviet Union. The Declaration partly restated the legal force of the constitutional basis of the pre-war Republic - the Satversme (Constitution). The Declaration expressed the desire: ' (...) To recognize the supremacy of the fundamental principles of intemafional law over national law. To consider illegal the Treaty of August 23, 1939 between the USSR and Germany, and the subsequent liquidation of the sovereignty of the Republic of Latvia on June 17, 1940 which was the result of the USSR military aggression. To declare null and void from the moment of adoption the Decision of July 21, 1940 of the Saeima of Latvia 'On the Republic of Latvia's Joining the USSR'. (...) To guarantee citizens of the Republic of Latvia and those of other States permanently residing in Latvia social, economic and Cultural rights, as well as those political rights and freedoms which comply with the universally recognized international human rights instruments (...). -

Importance of European Remembrance for the Future of Europe

European Parliament 2019-2024 TEXTS ADOPTED P9_TA(2019)0021 Importance of European remembrance for the future of Europe European Parliament resolution of 19 September 2019 on the importance of European remembrance for the future of Europe (2019/2819(RSP)) The European Parliament, – having regard to the universal principles of human rights and the fundamental principles of the European Union as a community based on common values, – having regard to the statement issued on 22 August 2019 by First Vice-President Timmermans and Commissioner Jourová ahead of the Europe-Wide Day of Remembrance for the victims of all totalitarian and authoritarian regimes, – having regard to the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted on 10 December 1948, – having regard to its resolution of 12 May 2005 on the 60th anniversary of the end of the Second World War in Europe on 8 May 19451, – having regard to Resolution 1481 of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe of 26 January 2006 on the need for international condemnation of crimes of totalitarian Communist regimes, – having regard to Council Framework Decision 2008/913/JHA of 28 November 2008 on combating certain forms and expressions of racism and xenophobia by means of criminal law2, – having regard to the Prague Declaration on European Conscience and Communism adopted on 3 June 2008, – having regard to its declaration on the proclamation of 23 August as European Day of Remembrance for the Victims of Stalinism and Nazism adopted on 23 September 20083, 1 OJ C 92 E, 20.4.2006, p. 392. 2 OJ L 328, 6.12.2008, p. -

Czechoslovak-Polish Relations 1918-1968: the Prospects for Mutual Support in the Case of Revolt

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1977 Czechoslovak-Polish relations 1918-1968: The prospects for mutual support in the case of revolt Stephen Edward Medvec The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Medvec, Stephen Edward, "Czechoslovak-Polish relations 1918-1968: The prospects for mutual support in the case of revolt" (1977). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5197. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5197 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CZECHOSLOVAK-POLISH RELATIONS, 191(3-1968: THE PROSPECTS FOR MUTUAL SUPPORT IN THE CASE OF REVOLT By Stephen E. Medvec B. A. , University of Montana,. 1972. Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1977 Approved by: ^ .'■\4 i Chairman, Board of Examiners raduat'e School Date UMI Number: EP40661 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

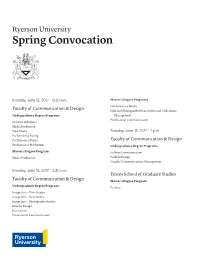

Ryerson University Spring Convocation

Ryerson University Spring Convocation Monday, June 12, 2017 • 9:30 a.m. Master’s Degree Programs Documentary Media Faculty of Communication & Design Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Undergraduate Degree Programs Management Professional Communication Creative Industries Media Production New Media Tuesday, June 13, 2017 • 1 p.m. Performance Acting Performance Dance Faculty of Communication & Design Performance Production Undergraduate Degree Programs Master’s Degree Program Fashion Communication Media Production Fashion Design Graphic Communications Management Monday, June 12, 2017 • 2:30 p.m. Yeates School of Graduate Studies Faculty of Communication & Design Master’s Degree Program Undergraduate Degree Programs Fashion Image Arts – Film Studies Image Arts – New Media Image Arts – Photography Studies Interior Design Journalism Professional Communication Convocation Program Monday, June 12, 2017 • 9:30 a.m. Eagle Staff Carrier Mace Carrier and Bedel Tracey King Cynthia Ashperger Aboriginal Human Resources Consultant Director Ryerson Aboriginal Student Services Acting Program School of Performance Convocation Ceremony Invocation Family and friends are requested to rise when the In the toil of thinking; in the serenity of books; in the academic procession enters, and remain standing until messages of prophets, the songs of poets and the wisdom the conclusion of the invocation. of interpreters; in discoveries of continents of truth whose margins we may see; we delight in free minds and in their Following the convocation address, the graduands will thinking. rise for the general presentation of candidates and then resume their seats. Afterwards, graduands will be called In the majesty of the moral order; in the faith that right and presented for the awarding of certificates, and will triumph; in the courage given us when we ally undergraduate and graduate degrees. -

Speaker of the Saeima, Two Deputy Speakers, a Secretary and a Deputy Secretary

The Presidium of the Saeima The work of the Saeima is managed by the Presidium, which is elected by the Saeima at the beginning of its term of office. The Presidium of the Saeima consists of five members of the Saeima – the Speaker of the Saeima, two Deputy Speakers, a Secretary and a Deputy Secretary. Nominations for the positions in the Saeima Presidium are submitted by Saeima members in writing, and voting on the nominees for each position is held simultaneously by secret ballot and by using ballot papers. The nominee who receives the most votes is deemed elected; however, the number of votes should not be less than the absolute majority of votes of the members present. Members of the Presidium are usually elected from the ru- ling parties represented in the Saeima; however, the Speaker In order to coordinate the activities of parliamentary of the Saeima may also be elected from the party which has groups and political blocs, as well as to settle matters not gained the largest number of seats in the Saeima. which are not covered by the Rules of Procedure, the The Presidium of the Saeima determines the internal ru- Council of Parliamentary Groups is formed. It consists les of the Saeima, gives opinions on the documents sub- of the Saeima Presidium and one Saeima member from mitted and forwards these documents as prescribed by each parliamentary group and political bloc. Decisions of the Rules of Procedure, prepares the agenda of Saeima the Council of Parliamentary Groups are only advisory. sittings, as well as confirms planned business trips. -

Captive Nations Week” of the William J

The original documents are located in Box 34, folder “Captive Nations Week” of the William J. Baroody Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 34 of the William J. Baroody Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library Captive Nations Week, 1975 By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation The history of our Nation reminds us that the traditions of liberty must be protected and preserved by each generation. Let us, therefore, rededicate ourselves to . the ideals of our own democratic heritage. In so doing, we manifest our belief that all men everywhere have the same inherent right to freedom that we enjoy today. In support of this sentiment, the Eighty-sixth Congress, by a joint resolution approved July 17, 1959 (73 Stat. 212), authorized and requested the President to proclaim the third week in July of each year as Captive Nations Week. NOW, THEREFORE, I, GERALD R. -

160 KAZACHONAK Katsiaryna / КАЗАЧЁНОК Катарина Latvian

Альманах североевропейских и балтийских исследований / Nordic and Baltic Studies Review. 2016. Issue 1 KAZACHONAK Katsiaryna / КАЗАЧЁНОК Катарина Latvian Society of Archivists / Латвийское общество архивистов Latvia, Riga / Латвия, Рига [email protected] COOPERATION OF LATVIAN BELARUSIANS WITH THE NON-BELARUSIAN POLITICAL ORGANIZATIONS OF LATVIA IN 1928—31 СОТРУДНИЧЕСТВО БЕЛОРУСОВ ЛАТВИИ С НЕБЕЛОРУССКИМИ ЛАТВИЙСКИМИ ПОЛИТИЧЕСКИМИ ОРГАНИЗАЦИЯМИ В 1928—1931 ГГ. Аннотация: В статье рассматривается вопрос о характере отношений представителей белорусского меньшинства Латвии с политическими партиями Латвии в период предвыборных кампаний в парламент второго и третьего coзывов. Именно в это время белорусы начали интенсивно искать контакты с другими политическими организациями Латвии. Поддержка белорусами социал-демократов и коммунистов была закономерна и обуславливалась социальной структурой белорусского меньшинства Латвии. В начале 1930-х гг. белорусы сделали попытку расширить свои контакты через взаимодействие с другими гражданскими партиями Латвии, которые, хотя и были левыми, выражали некоторые идеи, ранее не характерные для белорусских политических организаций (Латгальского объединения прогрессивных крестьян, Партии крестьян-христиан). Это свидетельствует, с одной стороны, о разочаровании в белорусских национальных политических партиях, а с другой стороны, о более глубокой интеграции белорусов в латвийское общество. Статья написана на основе архивных документов и периодической печати того времени, много информации из источников публикуется впервые. Kewords / Ключевые слова: Latvia, Latgalе, Belarusian minority, Belarusian political parties, parliamentary elections, the 3rd Saeima, the 4th Saeima / Латвия, Латгалия, белорусское меньшинство, белорусские политические партии, парламентские выборы, Третий Сейм, Четвёртый Сейм. In the 1920s and 1930s the Belarusians were one of the largest national minorities in Latvia. The majority of Belarusians lived in region of Latgale (the eastern part of Latvia) and Ilūkste Municipality (southeastern Latvia, part of Zemgale region).