GIPE-108324.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The London Gazette, December 6, 1881

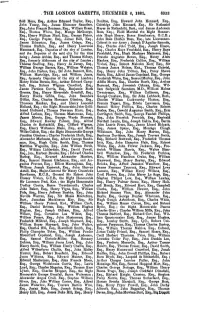

. THE LONDON GAZETTE, DECEMBER 6, 1881. 6553 'field Hora, Esq., Arthur Edmund Taylor, Esq., Doulton, Esq., Howard John Kennard, Esq., John Young, Esq., James Ebenezer Saunders, Coleridge John Kennard, Esq., Sir .Nathaniel Esq., John Francis Bontems, Esq., William Brass, Meyer de Rothschild, Bart, and James Anderson Esq., Thomas "White, Esq., Mungo McGeorge, Rose, Esq.; Field Marshal the Right Honour- Esq., Henry William Nind, Esq., George Fisher, able Hugh Henry, Baron Strathnairn, G.C.B. j Esq., George Pepler, Esq., James Bell, Esq., John Rose Holden Rose, Esq., late Lieutenant- James Edmeston, Esq., James Crispe, Esq., Colonel in our Army ; Joseph D'Aguilar Samuda, Thomas Rudkin, Esq., and Henry Lawrence Esq., Charles John Todd, Esq., Joseph Hoare, Hammack, Esq.. Deputies of the city of London, Esq., Charles Kaye Freshfield, Esq., Henry Raye and the Deputies of the said city for the time Freshfield, Esq., Hugh Mackaye Matheson, Esq., being ; James Abbiss, Esq., and Thomas Sidney, Francis Augustus Bevan, Esq., Henry Alers Esq., formerly Aldermen of the city of London ; Hankey, Esq., Frederick Collier, Esq., William Thomas Snelling, Esq., Henry de Jersey, Esq., Vivian, Esq., Robert Malcolm Kerr, Esq., Sir William George Barnes, Esq., William Webster, Thomas James Nelson, Knt., Thomas Gabriel, Esq., John Parker, Esq., Sir John Bennett, Knt., Esq., Henry John Tritton, Esq., Percy Shawe William Hartridge, Esq., and William Jones, Smith, Esq., Alfred James Copeland, Esq., George Esq., formerly Deputies of the city of London; Frederick White, Esq., Samuel Morley, Esq., John Henry Hulse Berens, Esq., Arthur Edward Camp- Alldin Moore, Esq., Charles Booth, Esq., Arthur bell, Esq., Robert Wigram Crawford, Esq., Burnand, Esq., Jeremiah Colman, Esq., Wil- James Pattison Currie, Esq., Benjamin Buck liam Sedgwick Saunders, M.D., William Holme Greene, Esq., Henry Riversdale Grenfell, Esq., Twentyman, Esq., William Collinson, Esq., Henry Hucks Gibbs, Esq., John Saunders George Croshaw, Esq., Sir John Lubbock. -

Whitehall, April^8-, 1842;

Hicks, Walter Anderson Peacock, Robert West- Venables, Josia.h, Wilson, Alfred Wils.cm, . wood, Thomas Quested Finqis, James, Ranishaw, Lea Wilson, Edward Lawford, Peter Laurie, Edward William Stevens, John Atkinson, James Southby Wilson, Richard Lea Wilson, Robert Ellis, William Bridge, John Brown, Edward Godson, Thomas Peters, James Walkinshaw, Joseph Somes, jun., Pewtress, Joshua Thomas Bedford, Henry John Samuel Gregson, William Hughes Hughes, jun., Eltnes, John William tipss, William Muddel), Henry Alexander Rogers, George Magnay, John Master- Prichard, Benjamin Stubbing, Henry Smith, man, jun., Daniel Mildred, Frederick Mildred, John. • Thomas Watkins, and George Wright, Esqi's., Meek Britten, Richard Lambert Jones, David Wij- Deputies of • the city of London, and the liams Wire, Charles Pearson, Thomas Saunder?, and. Deputies thereof for the time being ; John Garratt, James Cosmo Melville, Esqrs. Edward Tickner, Robert Williams, James Brogden, and Stephen Edward Thornton, Esqis., Sir Thomas Neave, Bart., Jeremiah Olive, Jeremiah Harman, ' Isaac Solly, Andrew Loughnan, Abel Chapman, Whitehall, April 25, 1842. Cornelius Buller, Wilj'mm Ward, and Melvil Wilson, . Esqrs,, Sir John Henry Felly, Bart., William Cotton, .The Queen has been graciously pleased, 'np'-n Robert Barclay, Edward Henry Chapman, Henry the nomination of his Grace the Duke of NorioJk, Davidson, Charles Pasr.oe Grenfell, Abel Lewes Earl Marshaland Hereditary Marshal of England,. Gower, Thomson Hankey, junr., John Oliver to appoint Edward Howard Gibbon, Esq. Moworay. Hanson, John Benjamin Heath, Kirkman Daniel Herald of Arms Extraordinary. • Hodgson, Charles Frederick Hiith, Alfred Latham, James Malcolmson, • Jauies Morris, Sheffield .Neave, George Warde. Norman, John .Horsley Palmer, James Pattison, • Christopher Pearse, Henry James Foreign-Office, May, 2, 1842: , Prescdtt, and Charles Pole, Esqrs., Sir John Rae Read, Bart., William R. -

January 2013 Abdul Bangura, Howard University, John Birchall

THE JOURNAL OF SIERRA LEONE STUDIES – Volume 2 – Edition 1 – January 2013 Editorial Panel Abdul Bangura, Howard University, John Birchall, Ade Daramy, David Francis, University of Bradford, Lansana Gberie, Dave Harris, School of Oriental and African Studies University of London, Philip Misevich, St John’s University, New York, John Trotman. Dedication I recently made contact with Professor John Hargreaves, who some of you will know was the last Editor of this Journal. He was delighted to hear of its re-appearance and so we have dedicated this edition to John and thank him for his scholarship and dedication to the academic life of Sierra Leone. In this edition Monetary Policy and the Balance of Payments: Econometric Evidence from Sierra Leone - Samuel Braima, Head of Economics Department, Fourah Bay College, University of Sierra Leone and Robert Dauda Korsu, Senior Economist, West African Monetry Agency. Addressing Organised Crime in Sierra Leone: The Role of the Security-Development Nexus - Sacha Jesperson, London School of Economics and Political Science. Book Review A Critique of Epistemologies of African Conflicts: Violence, Evolutionism and the War in Sierra Leone (New York: Palgrave, 2012) - Lans Gberie A new section We are pleased to introduce an end section that focuses on issues that will be of interest to those currently studying Sierra Leone and those who will follow this generation. In this edition we have: The naming of Sierra Leone - Peter Andersen Edward Hyde, Murray Town - pilot in The Battle of Britain. The chase for Bai Bureh - The London Gazette, 29th December, 1899. Peer Reviewed Section In this edition we have included a range of different articles. -

A Biographical Dictionary of Nineteenth Century Antique and Curiosity Dealers

This is a repository copy of A Biographical Dictionary of Nineteenth Century Antique and Curiosity Dealers. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/42902/ Book: Westgarth, MW (2009) A Biographical Dictionary of Nineteenth Century Antique and Curiosity Dealers. Regional Furniture, XXIII . Regional Furniture Society , Glasgow . Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/42902/ Published book: Westgarth, MW (2009) A Biographical Dictionary of Nineteenth Century Antique and Curiosity Dealers. Regional Furniture, XXIII . Regional Furniture Society White Rose Research Online [email protected] 148132:97095_book 6/4/10 10:11 Page cov1 REGIONAL FURNITURE 2009 148132:97095_book 6/4/10 10:11 Page cov2 THE REGIONAL FURNITURE SOCIETY FOUNDED 1984 Victor Chinnery President Michael Legg Vice President COUNCIL David Dewing Chairman Alison Lee Hon. -

Southside Virginian

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from LYRASIS members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/southsidevirgini1198283 THE SOUTHSIDE VIRGINIAN OCTOBER 1982 VOLUME 1, NUMBER 1 Reprinted May, 1991 THE SOUTHSIDE VIRGINIAN Volume 1 October 1?82 Number 1 Contents 1 From the Editors 2 Brunswick County Will Book 2 3 Amelia County Tithable List for 1737 15 Urquhart Family Cemetery, Southampton County 22 Account Book of Estates put into the Hands of the 23 Sheriff's Office, Nansemond County, 18^0- 1845 Register of Births and Deaths of William Browne and 24 Ann his wife of "Cedar Fields", Surry County. Some Importations from Lunenburg County Order Books 25 Wills from Southampton County Loose Papers 26 ^ Removals from Delinquent Tax Lists 30 Greensville County Powers of Attorney 31 Black Creek Baptist Church, Southampton County, ^3 Register of Births Queries 48 Lyndon H. Hart, J. Christian Kolbe, editors Copyright 1982 The subscription price is $15.00 per annum. All subscriptions begin with the October issue of the volume. Issues are not sold separately. Correspondence should be addressed: Box 118, Richmond, Virginia 23201. This is a reprint. For subscription information, contact: The Southside Virginian, P.O. Box 3684, Richmond, VA ' 23235. I FROM THE EDITORS The Southside Virginian is a genealogical quarterly devoted to to research in the counties of Southside Virginia, including the counties of Princess Anne, Norfolk, Nansemond, Isle of Wight, Southampton, Surry, Sussex, Prince George, Chesterfield, Dinwiddle, Powhatan, Greensville, Amelia, Nottoway, Brunswick, Cumberland, Prince Edward, Mecklenburg, Charlotte, Halifax, Henry, Pittsylvania. The purpose of this quarterly is to promote scholarly genealogical research in Southside Virginia by making available to its subscribers transcriptions and abstracts of county, church, and cemetery records. -

BUCKINGHAMSHIRE POSSE COMITATUS 1798 the Posse Comitatus, P

THE BUCKINGHAMSHIRE POSSE COMITATUS 1798 The Posse Comitatus, p. 632 THE BUCKINGHAMSHIRE POSSE COMITATUS 1798 IAN F. W. BECKETT BUCKINGHAMSHIRE RECORD SOCIETY No. 22 MCMLXXXV Copyright ~,' 1985 by the Buckinghamshire Record Society ISBN 0 801198 18 8 This volume is dedicated to Professor A. C. Chibnall TYPESET BY QUADRASET LIMITED, MIDSOMER NORTON, BATH, AVON PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY ANTONY ROWE LIMITED, CHIPPENHAM, WILTSHIRE FOR THE BUCKINGHAMSHIRE RECORD SOCIETY CONTENTS Acknowledgments p,'lge vi Abbreviations vi Introduction vii Tables 1 Variations in the Totals for the Buckinghamshire Posse Comitatus xxi 2 Totals for Each Hundred xxi 3-26 List of Occupations or Status xxii 27 Occupational Totals xxvi 28 The 1801 Census xxvii Note on Editorial Method xxviii Glossary xxviii THE POSSE COMITATUS 1 Appendixes 1 Surviving Partial Returns for Other Counties 363 2 A Note on Local Military Records 365 Index of Names 369 Index of Places 435 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The editor gratefully acknowledges the considerable assistance of Mr Hugh Hanley and his staff at the Buckinghamshire County Record Office in the preparation of this edition of the Posse Comitatus for publication. Mr Hanley was also kind enough to make a number of valuable suggestions on the first draft of the introduction which also benefited from the ideas (albeit on their part unknowingly) of Dr J. Broad of the North East London Polytechnic and Dr D. R. Mills of the Open University whose lectures on Bucks village society at Stowe School in April 1982 proved immensely illuminating. None of the above, of course, bear any responsibility for any errors of interpretation on my part. -

David Kynaston's Till Time's Last Sand: a History of the Bank of England, 1694-2013: a Review Essay

Charles R. Bean David Kynaston's till time's last sand: a history of the Bank of England, 1694-2013: a review essay Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Bean, Charles R. (2018) David Kynaston's till time's last sand: a history of the Bank of England, 1694-2013: a review essay. American Economic Review. ISSN 0002-8282 © 2018 American Economic Association This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/90516/ Available in LSE Research Online: October 2018 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. David Kynaston’s Till Time’s Last Sand: A History of the Bank of England, 1694-2013. A review essay by Charles R Bean* 28 August 2018 Abstract This essay reviews Till Time’s Last Sand, David Kynaston’s history of the Bank of England from its foundation in 1694 to the present day. -

Bagehot for Central Bankers Laurent Le Maux

Bagehot for Central Bankers Laurent Le Maux To cite this version: Laurent Le Maux. Bagehot for Central Bankers. 2021. hal-03201509 HAL Id: hal-03201509 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03201509 Preprint submitted on 19 Apr 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Bagehot for Central Bankers Laurent Le Maux* Working Paper No. 147 February 10th, 2021 ABSTRACT Walter Bagehot (1873) published his famous book, Lombard Street, almost 150 years ago. The adage “lending freely against good collateral at a penalty rate” is associated with his name and his book has always been set on a pedestal and is still considered as the leading reference on the role of lender of last resort. Nonetheless, without a clear understanding of the theoretical grounds and the institutional features of the British banking system, any interpretation of Bagehot’s writings remains vague if not misleading—which is worrisome if they are supposed to provide a guideline for policy makers. The purpose of the present paper is to determine whether Bagehot’s recommendation remains relevant for modern central bankers or whether it was indigenous to the monetary and banking architecture of Victorian times. -

The London Gazette, December 29, 1399

..86*50 THE LONDON GAZETTE, DECEMBER 29, 1399. Consolidated Chapelry of All Saints South well as those rendered by the Officers, Non-commis • Merstham.' sioned Officers, and Men of the Imperial Troops, " We therefore humbly pray that Your Majesty and Sierra Leone Frontier Police, and by the will be graciously pleased to take the premises District Commissioners and other officials in the into Your Royal consideration and to make such service of this Government, mentioned by him in Order in respect thereto as to Your Majesty iu his Despatch. Your Royal wisdom shall seem meet, 3. I also beg to bring to your most favourable " The SCHEDULE to which the foregoing notice the efficient manner in which the Senior Representation has reference. Naval Officers, viz.:—Captain A. L. Winsloe, . " The Consolidated Chapelry of All Saints Her Majesty's ship "Blake," Captain F. H. South Merstbam comprising :— Henderson, Her Majesty's ship "Fox," and " All that portion of the parish of Merstbam iu Captain R. S. Rolleston, Her Majesty's ship the county of Surrey and in the diocese of "Phoebe," co-operated with tlie Officer Co'm- Rochester which is bounded upon the south-west manding Troops and myself, and the valuable by the hereinafter described portion of the parish services rendered by Her Majesty's ships " Fox," of Gatton upon the south-east by the parish of « Phoebe," " Blonde," " Tartar," and " Alecto." Nutfield upon the east by the parish of Blechingley 4.' On the occasion of a reirifbrcemerit" of the all in the county and diocese aforesaid and upon 1st West India Regiment having been sent to the remaining sides that is to say upon the north Port Lokko on the 3rd March last, Captain and upon the north-west by an imaginary line Henderson, at my request, detailed a gun force to commencing at the point near the lodge at the cover the passage of the troops up the Lokko Creek entrance to the house and grounds called Coppice under Lieutenant F. -

Dame Patricia Laid to Rest PAGE 4

Established October 1895 Dame Patricia laid to rest PAGE 4 Saturday June 20, 2020 $1 VAT Inclusive Efforts on to improve CHICKEN GLUT Barbados’ water supply EFFORTS are on to improve the quality,reliability and efficiency of Barbados’ potable water sup- ply, as well as its wastewater system. Just yesterday, the Barbados Water Supply CAUSESWITH over 600,000 currently working at 40 per cent BusinessCUT and Entrepreneur- as supermarkets were wary of Infrastructure Rehabilitation kilograms of frozen chicken of its capacity due to the closure ship, Dwight Sutherland. being shut down at a moment’s Project was launched at the in stock, Chickmont Foods of many hotels and restaurants “You cannot stop the notice, so they were hesitant to Barbados Water Authority’s Limited will be slashing its during the national shutdown production of poultry buy fresh meats cause they did (BWA) Bowmanston Pumping days of operation to just two caused by the COVID-19 immediately, so while the not know if they were going to Station in St. John. per week. pandemic. country shut down, we were be stuck with it. Barbados is a Minister of Energy and Water Explaining the reason behind He highlighted the delayed still producing. You have fresh chicken market, so if you Resources, Wilfred Abrahams, the glut of this commodity, effect the shutdown had on the different ages of chickens on the cannot produce fresh, you have noted that the project, which is General Manager of Chickmont poultry industry during a tour farm and different ages of eggs to freeze it,” Albecker noted. being financed by the European Foods, Edward Albecker, said of the plant yesterday with in the hatchers aging. -

Rechtsgeschichte Legal History

Zeitschrift des Max-Planck-Instituts für europäische Rechtsgeschichte Rechts R Journal of the Max Planck Institute for European Legal History geschichte g Rechtsgeschichte Legal History www.rg.mpg.de http://www.rg-rechtsgeschichte.de/rg28 Rg 28 2020 183 – 198 Zitiervorschlag: Rechtsgeschichte – Legal History Rg 28 (2020) http://dx.doi.org/10.12946/rg28/183-198 Dieter Ziegler * DiePeelscheBankakteunddieStabilitätder Finanzmärkte in England, 1844–1890 [The Peel’s Act and the Stability of English Financial Markets, 1844–1890] * Ruhr-Universität Bochum, [email protected] Dieser Beitrag steht unter einer Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Abstract This article examines the evolution of central banking in England during the 19th century. Although the Bank of England was, during the period examined in this contribution, a privately- owned and privileged company, its money market operations (at least from 1873 onward) are always interpreted as the gradual adaption of the duties of a modern central bank, including the role as the »bankers’ bank«. The fact that it was also in com- petition with discount houses and commercial banks on the money market is, however, largely neglected. Contrary to conventional wisdom, this article analyses the Bank of England operations under the rationale of a utility-maximising institu- tion which had to hide that its principal business objectivewasahighandstabledividend. Keywords: Bank Charter Act of 1844, Bank of England, lender of last resort, Walter Bagehot □× Fokus focus Dieter Ziegler DiePeelscheBankakteunddieStabilitätder Finanzmärkte in England, 1844–1890 DerLondonerFinanzmarktwiesim›langen der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts zunächst nicht viel 19. Jahrhundert‹ eine beeindruckende Stabilität mehr hieß, als die Konvertibilität der Währung auf.NatürlichereignetensichauchindieserZeit durchdieBildungausreichender(Währungs-)Me- Bankenzusammenbrüche, darunter auch recht tallreserven bei der Zentralnotenbank zu sichern. -

The Baring Archive Series Hc3 British Isles

THE BARING ARCHIVE SERIES HC3 BRITISH ISLES House Correspondence – British Isles HC3 3.1 1817 12 Aug, London: Joseph Waugh & Sons to Barings About shares in the purchase of cochineal in South America, to be made by Reid Irving & Co. The shares to be one third each to Barings, Reid Irving and Waugh; with details of the conditions of purchase 3.2 1823-38, Gibraltar: John Duguid & Co, merchants, of Gibraltar, to Alexander Baring and to Barings 1823-32: Explaining adverse balances with Barings; the failure of Duguid Holland & Co, Buenos Aires [see HC4.1.4]; proposal to Barings to take up a mortgage on property in Gibraltar 1836-37: Visit to England of John Duguid; his death in London, 17 May 1837; reorganisation of the business under John Robert Duguid, the eldest son 1838: Seeking an extension of credit; credit extended to £3000; failure of Duguid & Co; debt to Barings of £14,500 3.3 1823-34, Austin Friars London: Thomson Bonar & Co to Barings 1823 8 Oct: About a contract with the Russian government whereby Thomson Bonar, Barings and others have obtained a monopoly of Russian government copper at St Petersburg 1827 15 Oct: Enclosing account of Horace Gray of Boston, Massachusetts [see HC5.1.12] for Georgia cotton shipped from Boston to St Petersburg for the Imperial Manufactory of Alexandroffsky 3.4 1824-29, London: Documents about the joint speculation in tobacco from Virginia, Maryland and Kentucky, undertaken by Barings and Kymer Patrey & Co, tobacco brokers, of Mincing Lane, London The documents are: correspondence; accounts; notices of receipt of tobacco at the docks at London and Liverpool; sales of tobacco; valuations of tobacco held in bond The correspondence includes: 1825 29 Jul: Kymer Patrey to Barings.