Poreč Monuments a Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radno Vrijeme Prodavaonica Od 23.03.2020

Radno vrijeme prodavaonica od 23.03.2020. Radno vrijeme prodavaonica od 23.03.2020. Mjesto Adresa Pon - pet Subota Nedjelja Višnjevac Bana Josipa Jelačića 137 08,00-17,00 08,00-13,00 08,00-13,00 Osijek Ive Tijardovića 4a 08,00-17,00 08,00-17,00 08,00-13,00 Osijek Stjepana Radića 33 08,00-17,00 08,00-13,00 ZATVORENO Osijek Sjenjak bb 08,00-17,00 08,00-17,00 08,00-13,00 08,00-13,00 Osijek Trg Ljudevita Gaja bb Ne radi ponedjeljkom 08,00-13,00 08,00-13,00 Osijek J.J.Strossmayera 192 08,00-17,00 08,00-13,30 08,00-13,00 Osijek Kamila Firingera 12 08,00-13,30 ZATVORENO ZATVORENO Osijek Josipa Rajhl-Kira 12 08,00-17,00 08,00-17,00 08,00-13,00 Osijek I.G.Kovačića 3 08,00-17,00 08,00-14,00 08,00-13,00 Osijek Vukovarska ulica 2 ZATVORENO ZATVORENO ZATVORENO Osijek Prolaz J.Leovića 1 08,00-17,00 08,00-14,00 08,00-13,00 Osijek Sv. Leopolda Mandića 111a 08,00-16,00 08,00-13,00 ZATVORENO Osijek Ribarska 1 08,00-17,00 08,00-13,00 ZATVORENO Osijek Trg Slobode 3 08,00-17,00 08,00-14,00 08,00-13,00 Osijek Marjanska 22 08,00-17,00 08,00-13,00 08,00-13,00 08,00-13,00 Osijek Trg Ljudevita Gaja bb Ne radi ponedjeljkom 08,00-13,00 08,00-13,00 Osijek Hrvatske Republike 19 08,00-17,00 08,00-14,00 ZATVORENO Osijek Sv. -

Investment Opportunity in Investment Opportunity in Motovun Area

Investment opportunity in Motovun area Motovun Situated in the center of heart-shaped Istria, one of the best-developed tourist regions and the biggest peninsula in Croatia, is the humble municipality of Motovun. Such location makes it close to other well-known tourist hotspots at the coast while keeping a more peaceful and easy-going surrounding. Poreč, Pula, and Rijeka are less than an hour's drive away and the nearest sea is less than 30 minutes' drive away. Situated in the heart of the peninsula, with mountain Učka on the east, the Adriatic Sea on the west and the river Mirna flowing through it, Motovun area has a unique continental climate with 4 distinct seasons. Old Motovun town, or Montona, is the best-preserved medieval town in Istria and dates to the 12th century A.D. Motovun sits atop the 277-meter high hill and is the center of Motovun municipality. While the whole municipality has a little over 1000 residents, it has more than 400 000 tourists a year who enjoy in what Motovun municipality offers. 1 Architecture The old town of Motovun is the best-preserved medieval town in Istria. The towers and city gates contain elements of Romanesque, Gothic, and Renaissance styles. The outer fortification wall, built in the 13th century, remains mostly intact to this day. The parish church of St. Stephen erected in place of an older church where, as the legend says, the margrave Engelbert of Istria and his wife countess Matilda were buried. Due to the mannerist elements of its façade, Motovuners consider it built after the design of the famous Venetian architect Andrea Palladio. -

Krajnovic Gortan Rajko

CULTURAL MANIFESTATION BASED ON RURAL TOURISM DEVELOPMENT- ISTRIAN EXAMPLE Aleksandra Krajnovi ćtel, Ph.D. Institute for Agriculture and Tourism – External Collaborator C. Hugues 8, 42 440 Pore č, Croatia Phone: +385 91 5465 536 E-mail address: [email protected] Ivana Paula Gortan-Carlin, M.Sc. Institute for Agriculture and Tourism Pore č – extern assistant „Department of Cakavian Assembly for Music“ Novigrad Podravska 23, 52466 Novigrad, Croatia Phone: +385 91 5247 555 E-mail address: [email protected] Mladen Rajko, Graduate Economist Institute for Agriculture and Tourism – External Collaborator C. Hugues 8, 42 440 Pore č, Croatia Phone: +385 91 1626 090 E-mail address: [email protected] Key words : Cultural Manifestation, Maintainable (Responsible) Tourism, Rural Tourism, Rural Tourist Destination 1. INTRODUCTION The competitiveness of Istrian rural areas as a tourism product is not satisfactory, as demonstrated by the stagnation of agritourism – the backbone of rural tourism – and the closing of farms, which has been occurring in recent years. The situation is even worse in some parts of Croatia. Increasing the competitiveness of rural tourism requires enhacing the recognizability of the rural destination. The best means to achieve this objective is "upgrading" agritourism – the basic product of rural tourism – with additional content. The above considerations lead to the following question: Which content is adequate for this type of tourism? This paper aims to show that cultural and entertainment events can contribute significantly to enhancing the basic product of rural tourism by conferring "added value" upon the destination. Cultural, entertainment, sports and other events can thus become an important factor in the sustainable development of tourism, especially in the valorisation of cultural heritage through tourism, thereby increasing the opportunities for its conservation, preservation and promotion, and addressing both tourists and the local population. -

Croatia Departures from Spring 2021

Croatia Departures from Spring 2021 Moving Encounters, Exploring the World Since 1992, 145 countries, 6 continents An industry leader for nearly 30 years, Classical Movements is happy to now offer additional tours for individuals and small groups, enabling lovers of the arts to travel around the world and experience the finest of local culture. Živjeli! The Balkan Peninsula is known around the world for its fascinating history and culture. Classical Movements has been hosting tours to Croatia since 1995, the first American tour company to do so. Balkan music, dance, and traditional food and costume have enchanted the world for centuries, and the migration of countless peoples through the region has left its mark. Experience the warmth and exceptional beauty of Croatia, from the renowned Plitvice Lakes, to the exquisite inland hills, to the almost-tropical beaches of the seemingly endless coast. Stop by lush vineyards, trek through ancient towns, and marvel at the incredible UNESCO World Heritage sites you will see on your tour. Home to movie sets and monasteries alike, the hospitality and luxurious climate of Croatia will leave you wanting more. PRICING, DATES, and INCLUSIONS (Subject to change) PRICE does not include airfare or airport transfers From $3,317.00 - $4,325.00 per person Prices are for small-group tours of 10-30 passengers. Bookings and pricing for individual groups of 2 or more passengers available on request. Prices subject to change based on fluctuations in the travel industry due to COVID-19. DATES May 25 - June 6, 2021 | July 5-17, 2021 | August 31 - September 12, 2021 or choose your own dates Date ranges indicate start of services to end of services and hotel nights provided. -

Hidden Istria

source: hidden europe 40 (summer 2013) text and pictures © 2013 Rudolf Abraham FEATURE www.hiddeneurope.co.uk Hidden Istria by Rudolf Abraham osip Zanelli walks slowly with me through Draguć is one of the most photogenic locations the lush grass in front of his stone house to anywhere in this corner of Croatia. J the diminutive Church of Sveti Rok, on the Vineyards spill down the hillside towards a edge of the village of Draguć. This little com- lake to the west called Butoniga jezero. The water 22 munity in Istria was once an important centre for is framed by a double rainbow that comes and the cultivation of silkworms, though nowadays it goes as rain clouds slowly give way to sunshine. is a quiet, little-visited place with fewer than 70 Standing in the small porch of the church, Josip inhabitants. It deserves to be in the limelight, for unlocks the old wooden door with a large key, and waves me inside to look at the cycle of 16th- A: Josip Zanelli unlocks the Church of Sveti Rok at Dragu. The church is famous for its cycle of 16th-century century frescoes which decorate the walls of its frescoes (photo by Rudolf Abraham). simple, dimly lit interior — an Adoration of the hidden europe 40 summer 2013 Trieste S Piran Sale Žejane Buzet Paladini Dragu Opatija Rijeka R : Istria in context. Our map shows historic Istria in its Pore entirety from the Golfo di Trieste to the southern tip of the Beram Istrian peninsula. Places mentioned in the text are marked Šunjevica on the map (map scale 1:1,000,000). -

An Adriatic Journey: from Trieste to Dubrovnik – 2022

An Adriatic Journey: from Trieste to Dubrovnik – 2022 18 SEP – 3 OCT 2022 Code: 22230 Tour Leaders Dr Christopher Gribbin, Martin Muhek Physical Ratings Enjoy Croatia’s Plitvice Lakes & one of the Mediterranean’s loveliest coasts with Dalmatia’s rich heritage of classical, medieval & Venetian monuments & towns incl. Hvar Island. Overview Dr Christopher Gribbin shows how Greek, Roman, Byzantine, Croat, Venetian, Austro-Hungarian and Turkish culture and trade travelled the sparkling Adriatic as you journey along Croatia's magnificent panoramic coastline. For the Croatian part of the tour, Chris will be accompanied by Martin Muhek, who brings a profound knowledge of the Balkan region to ASA tours. Visit 10 UNESCO World Heritage Cultural Sites: Ancient Roman and early Christian city of Aquileia: with brilliant mosaics in the 1000-year-old Patriarchal Basilica and an archaeological museum housing one of the most important collections of Roman artefacts in the world. Plitvice Lakes National Park: one of Europe's scenic wonders. Euphrasian Basilica, Porec: a masterpiece of the Byzantine world with mosaics to rival Ravenna. Historical centre of Trogir: a tiny island city, the Adriatic's best-preserved Romanesque-Gothic complex. Trogir Cathedral's portal sculptures are a particular delight. Old City of Dubrovnik: with spectacular city walls and a rich heritage as a great maritime power. Learn how this city-state avoided dominion by Venice and the Ottomans, and appreciate masterpieces of Venetian architecture in the city's churches and palaces. Diocletian's monumental palace at Split: the 4th-century Roman emperor's palace later transformed into a medieval fortified town and now forms the heart of the city of Split. -

Croatian Regions, Cities-Communes, and Their Population in the Eastern Adriatic in the Travelogues of Medieval European Pilgrims

359 Croatian Regions, Cities-Communes, and Their Population in the Eastern Adriatic in the Travelogues of Medieval European Pilgrims Zoran Ladić In this article, based on the information gathered from a dozen medieval pilgrim travelogues and itineraries,1 my aim has been to indicate the attitudes, impressions, and experiences noted down by sometimes barely educated and at other times very erudite clerical and lay pilgrims, who travelled to the Holy Land and Jerusalem as palmieri or palmarii2 ultra mare and wrote about the geographical features of the Eastern Adriatic coast, its ancient and medieval monuments, urban structures, visits to Istrian and Dalmatian communes, contacts with the local population, encounters with the secular and spiritual customs and the language, the everyday behaviour of the locals, and so on. Such information is contained, to a greater or lesser extent, in their travelogues and journals.3 To be sure, this type of sources, especially when written by people who were prone to analyse the differences between civilizations and cultural features, are filled with their subjective opinions: fascination with the landscapes and cities, sacral and secular buildings, kindness of the local population, ancient monuments in urban centres, the abundance of relics, and the quality of 1 According to the research results of French historian Aryeh Graboïs, there are 135 preserved pilgrim journals of Western European provenance dating from the period between 1327 and 1498. Cf. Aryeh Graboïs, Le pèlerin occidental en Terre sainte au Moyen Âge (Paris and Brussels: De Boeck Université, 1998), 212-214. However, their number seems to be much larger: some have been published after Graboïs’s list, some have been left out, and many others are preserved at various European archives and libraries. -

Istria, Croatia Poreč, a Place Where All the Values of Traditional and Modern Mediterranean Come Together

PorečIstria, Croatia Poreč, a place where all the values of traditional and modern Mediterranean come together. The charm of the old town with its mosaics and sights under the auspices of UNESCO, the tradition of wine and olives cultivation, local varieties and groceries, quiet coves, long coastline and green interior riches that we have inherited and preserved. But what specifically defines our past and builds our future is the art of providing a warm welcome since 1845, when Poreč was enlisted as tourist destination and when the first travel guide with a description of the town was printed. This town was preparing for more than 150 years for your arrival Poreč Istria, Croatia • mediterranean town, western coast of the Istrian peninsula, Croatia • tourism tradition since 1844 • Euphrasian Basilica – World Heritage Site with valuable mosaics, under the auspices of UNESCO • around 20,000 inhabitants • 37 kilometres of coastline • more than 3,850 sunshine hours per year • sea temperature during summer up to 28 degrees Celsius • the warmest month is August, 30 degrees Celsius • mild winters • 21 beaches awarded with Blue Flag, international symbol of preserved sea and coastline (20% of all Croatia’s Blue Flags!) SOME OF THE WORLD’S FAMOUS MOSAICS THAT ADORN OUR TOWN ARE ASSEMBLED IN THE 3RD CENTURY. AND SOME WILL BE ASSEM- Content Poreč, old town center 12 Activities 24 BLED UPON YOUR VISIT. Trips 42 Beaches and sea 48 Gourmet 52 Entertaiment 60 THOSE ARE MOSAICS 68 Accommodation THAT WERE CREATED BY EXPERIENCES, TILES WHICH WE COMPLE- MENT EACH DAY OVER AND OVER AGAIN WHILE EXPECTING YOU. -

Gems of Istrian Coast

Head office Slovenia Dunajska cesta 109, Ljubljana T: +386 1 232 11 71 E: [email protected] LIBERTY ADRIATIC Croatia offices Zagreb : Ilica 92/1; T: +385 91 761 08 85 www.liberty-adriatic.com Dubrovnik : Na Rivi 30a; T: +385 98 188 21 32 www.impact-tourism.net E: [email protected] Serbia office Terazije 45, Belgrade T: +381 11 334 13 48 E: [email protected] GEMS OF ISTRIAN COAST 3 days / 2 nights Discovering Slovenian coast and top sites of Croatian Istria TOUR HIGHLIGHTS • Visit Piran, Slovenian little Adriatic treasure • Get in touch with history in Porec, a UNESCO World Heritage Site • Enjoy Rovinj, one of the most “photogenic” towns in the Mediterranean GENERAL INFORMATION SLOVENIA The country of Slovenia lies in the heart of the enlarged Europe. It has a border with Italy, Austria, Hungary and Croatia. The capital Ljubljana is a modern, fresh, young, creative and surprising city. Slovenia, a green and diverse country between the Alps and the Mediterranean, boasts all the beauties of the Old World. When you want to experience Europe in one stroke, come to Slovenia. In just 20,273 square kilometres there are snow- covered mountains, a sea coast bathing in the Mediterranean sun, beautiful karst caves and thermal springs, narrow white-water canyons and wide slow moving rivers, high mountain lakes and lakes that disappear mysteriously underground at the start of summer, ancient villages and medieval cities, the antique castles and modern entertainment, countless vineyards with top quality wines, and the only primeval forest in Europe. -

Izvještaj O Radu Savjeta Mladih Grada Pazina Za 2019. Godinu

Izvještaj o radu za 2019. godinu Sadržaj Uvodne napomene ................................................................................................................................... 2 1. Saziv Savjeta mladih (2019. – 2022.) ................................................................................................. 3 2. Aktivnosti Savjeta mladih u 2019. godini .......................................................................................... 5 2.1. Osposobljavanje i umrežavanje ..................................................................................................... 6 2.2. Jačanje rada s mladima na lokalnoj razini ................................................................................... 10 2.3. Sudjelovanje u radu gradskih tijela ............................................................................................. 12 2.4. Suradnja s udrugama ................................................................................................................... 13 2.5. Promocija rada ............................................................................................................................. 16 3. Financijsko izvješće .......................................................................................................................... 17 1 Uvodne napomene Savjet mladih Grada Pazina osnovan je 24. prosinca 2007. godine temeljem Zakona o savjetima mladih („Narodne novine“ broj 23/07). Savjet mladih Grada Pazina (u daljnjem tekstu: Savjet mladih) osnovan je kao savjetodavno -

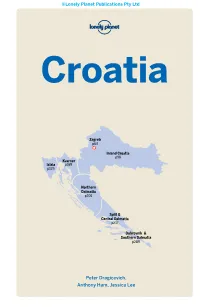

Croatia-10-Preview.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Croatia Zagreb p64 #_ Inland Croatia p98 Kvarner Istria p169 p125 Northern Dalmatia p206 Split & Central Dalmatia p237 Dubrovnik & Southern Dalmatia p289 Peter Dragicevich, Anthony Ham, Jessica Lee PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Croatia . 4 ZAGREB . 64 Buzet . 153 Croatia Map . .. 6 Sights . 65 Roč . 156 Hum . 156 Croatia’s Top 17 . 8 Tours . 79 Pazin . 157 Need to Know . 16 Festivals & Events . 81 Sleeping . 83 Svetvinčenat . 159 What’s New . 18 Eating . 85 Labin & Rabac . 160 If You Like . 19 Drinking & Nightlife . 87 Month by Month . 22 Entertainment . 92 KVARNER . 169 Itineraries . 26 Shopping . 93 Rijeka . 171 Outdoor Activities . 36 Around Rijeka . 176 Croatia’s Islands . 44 INLAND CROATIA . 98 Risnjak National Park . 176 Volosko . 177 Travel with Children . 52 Around Zagreb . 99 Samobor . 99 Opatija . 178 Eat & Drink Like a Local . 55 Mt Medvednica . 102 Učka Nature Park . .. 180 Lošinj & Cres Islands . .. 181 Regions at a Glance . 60 Zagorje . 103 Klanjec . 104 Beli . 182 Krapinske Toplice . 104 Cres Town . 183 IASCIC/SHUTTERSTOCK © IASCIC/SHUTTERSTOCK Krapina . 105 Valun . 185 Varaždin . 107 Lubenice . 186 Međimurje . 111 Osor . 186 Slavonia . 112 Nerezine . 187 Ðakovo . 113 Mali Lošinj . 187 Osijek . 114 Veli Lošinj . 190 Baranja . 119 Krk Island . 192 Vukovar . 121 Malinska . 192 Ilok . 123 Krk Town . 193 Punat . 195 KOPAČKI RIT NATURE PARK P119 ISTRIA . 125 Vrbnik . 195 Baška . 196 Istria’s West Coast . 127 East Kvarner Coast . 198 Pula . 127 JUSTIN FOULKES/LONELY PLANET © PLANET FOULKES/LONELY JUSTIN Crikvenica . 198 Brijuni Islands . 134 Senj . 199 Vodnjan . 135 Rab Island . 200 Bale . 136 Rab Town . -

11 Unesco Sites Tour

11 UNESCO SITES TOUR Visit 11 UNESCO SITES TOUR web page Visit 4 countries with 11 UNESCO sites in just 13 days! Explore the Škocjan Caves in Slovenia, hike around the OVERVIEW Plitvice Lakes, walk across the Mostar bridge, Dubrovnik city walls and explore Kotor Bay. DAY Ljubljana arrival Arrival at Ljubljana airport, where you'll be met by the local guide/driver who will take you to the hotel. Free 1 time for relaxation and, in the afternoon, sightseeing tour of the old town. Overnight in Ljubljana. DAY Ljubljana – Lakes Bled & Bohinj – Ljubljana In the morning we start the private tour in Slovenia with a drive to Bled to admire the beautiful Alpine lake with its charming island and castle 130 metres above the lake. We then drive deeper into the Julian Alps to 2 explore another Alpine pearl – Bohinj, with a cable car ride to Mt. Vogel. In the evening transfer to Ljubljana. DAY Ljubljana – Idrija – Ljubljana After breakfast, we drive towards Idrija to visit the UNESCO protected mercury mine which used to be one of the largest in the world. Visit of the mine and short walk through the town centre. In the afternoon we drive 3 back to Ljubljana. Overnight in Ljubljana. DAY Ljubljana – Škocjan Caves – Poreč – Rovinj Our drive takes us to another UNESCO site in Slovenia – the Škocjan Caves. Later we head towards Croatia and its northern coastal region, Istria. Our next visit is Poreč and the Euphrasian Basilica from the 6th century 4 – another UNESCO site. In the afternoon drive to and overnight in Rovinj.