Archetypal Patterns of Politics in Third Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

Iacs2017 Conferencebook.Pdf

Contents Welcome Message •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 4 Conference Program •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 7 Conference Venues ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 10 Keynote Speech ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 16 Plenary Sessions •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 20 Special Sessions •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 34 Parallel Sessions •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 40 Travel Information •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 228 List of participants ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 232 Welcome Message Welcome Message Dear IACS 2017 Conference Participants, I’m delighted to welcome you to three exciting days of conferencing in Seoul. The IACS Conference returns to South Korea after successful editions in Surabaya, Singapore, Dhaka, Shanghai, Bangalore, Tokyo and Taipei. The IACS So- ciety, which initiates the conferences, is proud to partner with Sunkonghoe University, which also hosts the IACS Con- sortium of Institutions, to organise “Worlding: Asia after/beyond Globalization”, between July 28 and July 30, 2017. Our colleagues at Sunkunghoe have done a brilliant job of putting this event together, and you’ll see evidence of their painstaking attention to detail in all the arrangements -

Reflections on Progressive Media Since 1968

THIRD WORLD NEWSREEL Reflections on Progressive Media Since 1968 CREDITS 2008 Editor: Cynthia Young 2018 Editors: Luna Olavarría Gallegos, Eric Bilach, Elizabeth Escobar and Andrew James Cover Design: Andrew James Layout Design: Luna Olavarría Gallegos Cover Photo: El Pueblo Se Levanta, Newsreel, 1971 THIRD WORLD NEWSREEL BOARD OF DIRECTORS Dorothy Thigpen (former TWN Executive Director) Sy Burgess Afua Kafi Akua Betty Yu Joel Katz (emeritus) Angel Shaw (emeritus) William Sloan (eternal) The work of Third World Newsreel is made possible in part with the support of: The National Endowment for the Arts The New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the NY State Legislature Public funds from the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council The Peace Development Fund Individual donors and committed volunteers and friends TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. TWN Fifty Years..........................................................................4 JT Takagi, 2018 2. Foreword....................................................................................7 Luna Olavarría Gallegos, 2015 3. Introduction................................................................................9 Cynthia Young, 1998 NEWSREEL 4. On Radical Newsreel................................................................12 Jonas Mekas, c. 1968 5. Newsreel: A Report..................................................................14 Leo Braudy, 1969 6. Newsreel on Newsreel.............................................................19 -

2 Postcolonial and Transnational Approaches to Film and Feminism

2 POSTCOLONIAL AND TRANSNATIONAL APPROACHES TO FILM AND FEMINISM Sandra Ponzanesi Since the 1990s, feminist film studies has expanded its analytic paradigm to interrogate the representation of race, ethnicity, religion, sexuality, and the nation (Wiegman 1998). This has included a new understanding of the role of audiences, consumption, and participatory culture, and a shift from textual analysis to broader cultural studies perspectives that include the role of institutions, reception, and technology. This is especially due to the contribution of black feminism in the US (see Hollinger 2012), and its critique of psychoanalysis as a Western universalistic framework of patriarchy (see Gaines 1986; Doane 1991; hooks 1992; Young 1996; Kaplan 1997), and the rise of postcolonial studies following the milestone publication of Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978) and its aftermath. The development of postcolonial studies strongly impacted the way of analyzing rep- resentations of the Other, asking for a rethinking of long-standing tropes and stereotypes about cultural difference, and also the gendering and racialization of otherness. This ushered in methodological interrogations on how visual representations are implicated in the policing of boundaries between East and West, between Europe and the Rest, the self and the other. The postcolonial paradigm is called upon to challenge the implicit and intrinsic Eurocentrism of much media representation and film theory (Shohat & Stam 1994), which implies a colonization of the imagination, where the Other is structurally and ideologically seen as deviant. Eurocentrism shrinks cultural heterogeneity into a single paradigmatic perspective in which Europe, and by extension the West, is seen as a unique source of meaning and ontological reality. -

Manifest Density: Decentering the Global Western Film

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2018 Manifest Density: Decentering the Global Western Film Michael D. Phillips The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2932 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] MANIFEST DENSITY: DECENTERING THE GLOBAL WESTERN FILM by MICHAEL D. PHILLIPS A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 Michael D. Phillips All Rights Reserved ii Manifest Density: Decentering the Global Western Film by Michael D. Phillips This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. __________________ ________________________________________________ Date Jerry W. Carlson Chair of Examining Committee __________________ ________________________________________________ Date Giancarlo Lombardi Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Paula J. Massood Marc Dolan THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Manifest Density: Decentering the Global Western Film by Michael D. Phillips Advisor: Jerry W. Carlson The Western is often seen as a uniquely American narrative form, one so deeply ingrained as to constitute a national myth. This perception persists despite its inherent shortcomings, among them its inapplicability to the many instances of filmmakers outside the United States appropriating the genre and thus undercutting this view of generic exceptionalism. -

Javier De Taboada Harvard University Del Tercer Cine Al Cine

REVISTA DE CRÍTICA LITERARIA LATINOAMERICANA Año XXXVII, No 73. Lima-Boston, 1er semestre de 2011, pp. 37-60 TERCER CINE: TRES MANIFIESTOS Javier de Taboada Harvard University Resumen En los años 60, el cine latinoamericano se distancia de su tradición previa, construida a imitación del modelo industrial de Hollywood, e irrumpe en el pa- norama del cine mundial. Nuevos cineastas plantean un cine político que abor- de las cuestiones sociales urgentes del momento y que rompa radicalmente la pasividad del espectador. La actividad de estos cineastas fue tanto práctica co- mo teórica, esta última expresada en manifiestos que replantean todo el proce- so de realización cinematográfica, desde su producción hasta su exhibición. El presente trabajo analiza tres de los más influyentes de estos manifiestos, explo- rando sus posibilidades, límites y contradicciones. Palabras clave: Fernando Solanas, Octavio Getino. Glauber Rocha, Julio García Espinosa, Tercer Cinema, manifiestos, Nuevo Cine Latinoamericano. Abstract In the 60s, Latin American cinema distances itself from its previous tradition, modeled around Hollywood’s industry, and emerges into the landscape of World Cinema. New filmmakers propose a political cinema that addresses the urgent social problems of the time and radically breaks with the passivity of the spectator. The activity of these filmmakers was both practical and theoretical, the latter expressed in manifestos which rethink the whole filmmaking process, from production to exhibition. This essay analyzes three of the most influential -

Toward a Third Cinema Now, Then, Armed Struggle Allows These Communities to Reenter History

popular sentiment. Mother, How beautiful to fight for liberty! There is a message of justice in each bullet I shoot, Old dreams that take wing like birds. sings Jorge Rebelo of Mozambique. How will the new culture develop? Only time will tell. One fact is certain: we have not completely lost the ancient thread of our authentic culture; the cultures of Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea are not dead. We still have a heritage. In spite of the slave trade, military conquest, and administrative occupation, in spite of forced labor and detribalization, the village communities have preserved in differing states of alteration their traditional culture. Isn't it true that the new culture born in the heat of battle will be a process of confirmation of the nations of Angola, Mozambique, Guinea, and Cape Verde? Certainly, since cultural community - together with language, territory, and economic life - is the fourth aspect of nationhood. This schema defined by Stalin continues to guide our investigations and today makes us view the national community as a relative linguistic,- politico-economic, and cultural unit. We know the process by which Portuguese colonialization prevented our dif- ferent countries from attaining a national existence. The most common result of colonialization is the break in the historical con- new tinuity of the old bonds between men, from both a family and an ethnic viewpoint. The colonial status which unites men in a market economy at e the lowest level, which depersonalizes them culturally, negates nationhood. Toward a Third Cinema Now, then, armed struggle allows these communities to reenter history. -

List of Digital Theatres for UFO Movies India Ltd

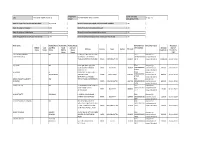

List of Digital Theatres For UFO Movies India Ltd. S.No. THEATRE_CODE THEATRE_NAME ADDRESS1 CITY ACTIVE PAYEE_CODE DISTRICT STATE COMPANY_NAME CMP_CODE SEATING INS_DATE WEB_CODE Main Road, Tagarapuvalasa, Ganesh 1 TH1177 Vizaq, Pin - 531162, Andhra Visakhapatnam Y 1 Visakhapatnam ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 537 9/26/2011 3235 (Tagarapuvalasa) Pradesh Bowdava Road, Vizag, Pin - 2 TH1178 Gokul Visakhapatnam Y 1 Visakhapatnam ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 515 9/26/2011 3244 530004, Andhra Pradesh Main Road, Parvathipuram, Sri Veerabhadra 3 TH1180 Dist-Vijayanagaram, Pin Parvathipuram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 396 9/26/2011 3698 Picture Palace Code - 535501 AP Radhamadhav Chipurupalli, 4 TH1181 Theatre Vizianagaram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 517 9/26/2011 3717 Vijayanagaram (Chipurupalli) 5 TH1182 N.C.S. Theatre A/C Vizianagaram, Pin - 535001 Vizianagaram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 577 9/26/2011 2696 Sri Vasavi Kala Main Road, Bobbili, 6 TH1183 Vizianagaram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 475 9/26/2011 2700 Mandir (Bobbili) Vizianagaram, Sri Ramanaah 7 TH1184 Theatre Devarapalli, West Godavari Vizianagaram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 371 9/26/2011 2689 (Devarapalli) Main Road, Moidha Sri Satya Theatre 8 TH1185 Junction, Nellimarla, Vizianagaram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 258 9/26/2011 2588 (Nellimarla) Vizianagaram, Pin - 535217 LakshmiLakshmi KKrishnarishna 9 TH1186 Janagoan, Warangal, AP Janagoan Y 1 Warangal ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 747 9/26/2011 832 Deluxe Sri Venkateshwara Main Road, Maripeda - 10 TH1187 Maripeda Y 1 Warangal ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 459 9/26/2011 2653 Theatre 506315, Dist Warangal Main RoadRoad,, MariMaripeda,peda, Dist.-Dist. -

Preservation of Culture Through Promotion of Linguistic Cinema In

International Journal of Advanced Mass Communication and Journalism 2020; 1(1): 33-38 E-ISSN: XXXX-XXXX P-ISSN: XXXX- XXXX IJAMCJ 2020; 1(1): 33-38 Preservation of culture through promotion of © 2020 IJAMCJ www.masscomjournal.com linguistic Cinema in India: A critical analysis Received: 08-11-2019 Accepted: 09-12-2019 Dr. Neeraj Karan Singh and Ambar Pandey Dr. Neeraj Karan Singh Faculty of Journalism & Mass Communication, Swami Abstract Vivekenand Subharti In India, cinema is very near to the lives of people or we can say that it is in the heart of the people. University, Meerut, The large screen provides an alternative, an escape from the realities of day-to-day life. People cry, Uttar Pradesh, India. laugh, sing, dance and enjoy emotions through cinema. The Cinema of India comprises of films made from corner to corner in India. Film has huge acclaim in the nation. Upwards of 1800 motion pictures Ambar Pandey in various languages are framed in consistently. The quantity of movies made and the quantity of Faculty of Journalism & Mass tickets are selling. Indian film is the biggest film industry on the planet in 2011 over 3.5 billion tickets Communication, Swami were sold over the world. Indian movies have an expansive all through Southern Asia and are realistic Vivekenand Subharti in standard films crosswise over different pieces of Asia, Europe, the Greater Middle East, North University, Meerut, America, Eastern Africa, and somewhere else. Indian film is viewed as the world's biggest film Uttar Pradesh, India. industry with profound respect to the quantity of movies it produce and the quantity of individuals working inside the film government. -

CIN COMPANY NAME First Name Middle Name Last Name Father

COMPANY DATE OF AGM CIN L29130MH1962PLC012340 FAG BEARINGS INDIA LIMITED 25-Apr-13 NAME (DD-MON-YYYY) Sum of Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend 383752.00 Sum of interest on unpaid and unclaimed Dividend 0.00 Sum of matured Deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured Debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 First name Father/Husb Father/Hus Father/Husb Folio Number Investment type Proposed Middle Last and First band and Last of Securities Amount date of Address Country State District PIN Code Name Name Name Middle Name Due(in Rs.) transfer to Name Name IEPF TH CENTURY FINANCE NIL IIT HOUSE OPP VAZIR GLASS FAG Amount for CORPORATION LT WORKS OFF M VASANJI 000000000001 unclaimed and ROAD,ANDHERI(E) MUMBAI INDIA MAHARASHTRA 400059 0874 unpaid dividend 11000.00 01-Jun-2014 A C DAVE NA BANK OF INDIA SOCIETY FAG Amount for NEAR SHARDA MANDIR INDIA GUJARAT 380007 00000000000 unclaimed and 200.00 01-Jun-2014 ROAD PALDI 01023 unpaid dividend A SANKAR R DOOR NO.70 FIRST STREET FAG Amount for ARUMUGAM VARNAPURAM INDIA TAMIL NADU 638301 00000000000 unclaimed and 400.00 01-Jun-2014 BHAVANI(P.O.) ERODE 27628 unpaid dividend ABDUL KADAR ALLARAKH NA SHIVAJI ROAD, KOPARGAON. FAG Amount for RANGREJ INDIA MAHARASHTRA 413709 000000000000 unclaimed and 480.00 01-Jun-2014 0479 unpaid dividend ABIDA A DESAI NA 14 KHURSHID PARK SARKHEJ FAG Amount for ROAD AHMEDABAD IN3012761073 unclaimed and INDIA GUJARAT 380055 20.00 01-Jun-2014 -

Cinema Novo and New/Third Cinema Revisited: Aesthetics, Culture and Politics Author(S): Ana Del Sarto Source: Chasqui, Vol

Cinema Novo and New/Third Cinema Revisited: Aesthetics, Culture and Politics Author(s): Ana del Sarto Source: Chasqui, Vol. 34, Special Issue No. 1: Brazilian and Spanish American Literary and Cultural Encounters (2005), pp. 78-89 Published by: Chasqui: revista de literatura latinoamericana Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/29742031 Accessed: 05-03-2017 15:36 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Chasqui: revista de literatura latinoamericana is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Chasqui This content downloaded from 140.233.2.215 on Sun, 05 Mar 2017 15:36:17 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms CINEMA NOVO AND NEW/THIRD CI? NEMA REVISITED: AESTHETICS, CUL? TURE AND POLITICS Ana Del Sarto Bowling Green State University During the 1960s, three dissimilar but interrelated aesthetic projects were conflated under the rubric of what later became known as the New Latin American Cinema: Imperfect Cinema from Cuba, New Cinema and, later, Third Cinema from Argentina and Cinema Novo from Brazil. As the title of my essay states, I will only focus my analysis on a comparison between Cinema Novo and New/Third Cinema.1 Both shared a general context of emergence and similar theoretical purposes; however, in practice many differences arose mainly related to the specific characteristics of each local context and the concrete articulations between the aesthetic, the cultural and the political. -

STUDY on the IMPACT of CREATIVE LIBERTY USED in INDIAN HISTORICAL SHOWS and MOVIES H S Harsha Kumar HOD, Department of Journalis

INTERNATIONALJOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARYEDUCATIONALRESEARCH ISSN:2277-7881; IMPACT FACTOR :6.514(2020); IC VALUE:5.16; ISI VALUE:2.286 Peer Reviewed and Refereed Journal: VOLUME:10, ISSUE:1(4), January :2021 Online Copy Available: www.ijmer.in STUDY ON THE IMPACT OF CREATIVE LIBERTY USED IN INDIAN HISTORICAL SHOWS AND MOVIES H S Harsha Kumar HOD, Department of Journalism, Government First Grade College Vijayanagar, Bangalore Introduction Historical references in movies, shows are the latest trends in the entertainment industry. In India there are more than 150 movies and 40 T.V shows approximately produced on the historical events and records. Many of these produced by the various makers to retell the tales of glory and valour of India’s great heroes do provide justice to the heroes to some extent. Authentic and accurate depictions for the sake of knowledge or even getting the glimpses of the history is not the outcome of these shows or movies. Various inconsistencies, differences and various inaccuracies regarding the script, scenes and execution, laymen are often misdirected towards concepts. The idea of creative liberty or artistic license used by the writers to make the best of the historical references provided may cause discrepancies or irregularities difficult to accept by the people or some intellectuals. But, to demand accuracy and authenticity from the Indian historical is, for its fans, to miss the point. The genre, after all, is that the descendant of Indian traditions of myth, folklore, ballads and popular history, which have combined to inform us more about an imagined past than an actual one.