Working Papers Conflicting Conceptualisations Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Timetable

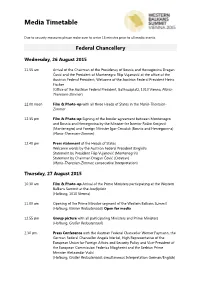

Media Timetable Due to security measures please make sure to arrive 15 minutes prior to all media events. Federal Chancellery Wednesday, 26 August 2015 11.55 am Arrival of the Chairman of the Presidency of Bosnia and Hercegovina Dragan Čović and the President of Montenegro Filip Vujanović at the office of the Austrian Federal President; Welcome of the Austrian Federal President Heinz Fischer (Office of the Austrian Federal President, Ballhausplatz, 1010 Vienna, Maria- Theresien-Zimmer) 12.00 noon Film & Photo-op with all three Heads of States in the Maria-Theresien- Zimmer 12.35 pm Film & Photo-op Signing of the border agreement between Montenegro and Bosnia and Hercegovina by the Minister for Interior Raško Konjević (Montenegro) and Foreign Minister Igor Crnadak (Bosnia and Herzegowina) (Maria-Theresien-Zimmer) 12.40 pm Press statement of the Heads of States Welcome words by the Austrian Federal President (English) Statement by President Filip Vujanović (Montenegrin) Statement by Chairman Dragan Čović (Croatian) (Maria-Theresien-Zimmer; consecutive Interpretation) Thursday, 27 August 2015 10.30 am Film & Photo-op Arrival of the Prime Ministers participating at the Western Balkans Summit at the Josefsplatz (Hofburg, 1010 Vienna) 11.00 am Opening of the Prime Minister segment of the Western Balkans Summit (Hofburg, Kleiner Redoutensaal) Open for media 12.55 pm Group picture with all participating Ministers and Prime Ministers (Hofburg, Großer Redoutensaal) 2.30 pm Press Conference with the Austrian Federal Chancellor Werner Faymann, the -

Österreich Hat Eine Bundeskanzlerin

Ausg. Nr. 185 • 5. Juni 2019 Das unparteiische, un ab hängige Ma ga - zin für Österrei cherinnen und Österrei - cher in aller Welt erscheint zehn Mal im Jahr in vier verschiedenen pdf-Formaten http://www.oesterreichjournal.at Österreich hat eine Bundeskanzlerin Foto: HBF / Carina Karlovits Peter Lechner Foto: HBF Die bisherige Verfassungsgerichtshof-Präsidentin Brigitte Bierlein – im Bild mit Bundespräsident Alexander Van der Bellen – wird nach Enthebung der ÖVP/FPÖ- Koalitionsregierung mit ihrer Regierungsmannschaft bis zur Einsetzung einer im September neu zu wählenden Bundesregierung unser Land nach innen und außen repräsentieren. Seite 46 Sie sehen hier die Variante A4 mit 72 dpi und geringer Qualität von Bildern und Grafiken ÖSTERREICH JOURNAL NR. 185 / 05. 06. 2019 2 Die Seite 2 Liebe LeserInnen, liebe Landsleute, während wir an der vorliegenden Ausgabe gearbeitet haben, ist uns die Regierung „abhandengekommen“. Das bedeutet, daß in einigen Beiträgen über Regierungsmitglieder berichtet wird, die zum Zeitpunkt unseres Er- scheinens nicht mehr ihre Funktionen innehatten. Apropos Regierung: ab der Seite 46 fassen wir zusammen, wie es zum Bruch der Koaltionsregierung gekommen ist und zeichnen den Weg bis zur Angelo- Wahl zum Europäischen Parlament 3 bung der Übergangsregierung unter Bundeskanzlerin Brigitte Bierlein nach. Liebe Grüße aus Wien Michael Mössmer Der Inhalt der Ausgabe 185 Wahl zum EU-Parlament 2019 3 Tourismusforum Burgenland 69 Van der Bellen trifft Putin 11 »Blaufränkischland pur« Kampf gegen Antisemitismus stündlich Wien/Deutschkreutz 70 als zentrales Anliegen 13 Eisenstadts Bürgerbudget 71 Neuwahl im September 46 Fest der Freude 15 FH Burgenland: erste Promotion 72 Aus dem Außenministerium 18 Jo und der krumme Teufel 73 Europa ist ein Europa der Regionen 23 ORF: »Die große Burgenland Tour« 74 UNESCO-Welterbe Präsentation 24 Salon Europa Forum Wachau 25 Die Zauberflöte in St. -

Dissertation / Doctoral Thesis

DISSERTATION / DOCTORAL THESIS Titel der Dissertation /Title of the Doctoral Thesis The dark side of campaigning. Negative campaigning and its consequences in multi-party competition. verfasst von / submitted by Mag. Martin Haselmayer angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doktor der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) Wien 2018 / Vienna 2018 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / A 784 300 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Dissertationsgebiet lt. Studienblatt / Politikwissenschaft / Political Science field of study as it appears on the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang C. Müller Assoc. Prof. Thomas Meyer, PhD Contents 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 The road thus far: Research on negative campaigning 4 Enhancing the understanding of negative campaigning 16 Implications 22 Plan of the dissertation 27 2 Sentiment Analysis of Political Communication: Combining a Dictionary Approach with Crowdcoding ............................................................................................................. 29 Introduction 30 Measuring sentiment in political texts 31 Employing crowdcoding to create a sentiment dictionary 34 Building a negative sentiment dictionary 35 Scoring sentences and texts 40 Validating the procedure 41 Applications 45 Conclusions 50 3 Friendly fire? Negative Campaigning Among Coalition Partners ........................... -

Austria Election Preview: Sebastian Kurz and the Rise of the Austrian ‘Anti-Party’ Page 1 of 4

LSE European Politics and Policy (EUROPP) Blog: Austria election preview: Sebastian Kurz and the rise of the Austrian ‘anti-party’ Page 1 of 4 Austria election preview: Sebastian Kurz and the rise of the Austrian ‘anti-party’ Austria goes to the polls on 15 October, with the centre-right ÖVP, led by 31-year-old Sebastian Kurz, currently ahead in the polls. Jakob-Moritz Eberl, Eva Zeglovits and Hubert Sickinger provide a comprehensive preview of the vote, writing that although polling is consistent with the idea the ÖVP and Kurz are the probable election winners, a noteworthy number of voters are still undecided. Kurz becoming the next chancellor is thus not as set in stone as Angela Merkel’s win in Germany was. Credit: Michael Tholen (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) Austria’s last parliamentary election in September 2013 resulted in two new parties gaining parliamentary representation, the populist Team Stronach (founded by billionaire Frank Stronach) and the liberal NEOS, while the BZÖ, Jörg Haider’s party which was in government between 2002 and 2006, failed to pass the threshold for parliamentary representation. The governing parties, the Social Democrats (SPÖ) and the People’s Party (ÖVP), recorded all-time lows in support, but still formed a coalition after the election. Team Stronach, however, deteriorated into insignificance very soon afterwards. Since then, however, Austrian voters have become increasingly dissatisfied with the performance of the SPÖ- ÖVP government. Eventually, the so-called refugee crisis in 2015 led to the right-wing populist FPÖ surging into first place in the polls. Soon after, in 2016, both government parties suffered a heavy defeat in the presidential elections, when their candidates gained only around 10% of the vote each, and failed to participate in the second, decisive round of the contest. -

Nationalrates 28

Nn ATIO ALRAT Bilanz 2008–2013 XXIV. GESETZGEBUNGSPERIODE DES NATIONALRATES 28. Oktober 2008 bis 28. Oktober 2013 Bilanz XXIV. GESETZGEBUNGSPERIODE DES NATIONALRATES (2008–2013) Impressum: Herausgeberin/Medieninhaberin/Herstellerin: Parlamentsdirektion Adresse: Dr. Karl Renner-Ring 3, 1017 Wien Konzeption: Gerhard Marschall Redaktion: Barbara Blümel, Harald Brunner, Gudrun Faudon-Waldner, Ute Krycha-Weilinger, Andreas Pittler, Dieter Weisser Fotoredaktion: Ute Krycha-Weilinger, Bernhard Zofall Layout/Graphik einschließlich Titelbild: Dieter Weisser Titelfoto: Stefan Olah Statistik Info-Grafiken: Harald Brunner Statistik (Zahlen): Hans Achter Externes Lektorat: PROperformance KG onlinelektorat, [email protected] Druck: Gutenberg-Werbering GmbH ISBN: 978-3-901991-27-1 Wien, im Oktober 2013 INHALT Editorial Nationalratspräsidentin Barbara Prammer: Bilanz fällt positiv aus ................................................. 5 Bilanz der Gesetzgebungsperiode Gastkommentar Theo Öhlinger: Demokratie ist ein mühsames Geschäft .......................................... 6 Finanz- und Wirtschaftspolitik Aktives Parlament in Zeiten der Krise ............................................................................. 10 Gastkommentar Norbert Feldhofer: Österreichische Stabilisierungspolitik......................................... 11 Gastkommentar Harald Waiglein: Neue finanz- und wirtschaftspolitische Steuerungsarchitektur .................. 13 Gastkommentar Klaus Liebscher: Europäische und österreichische Reaktionen auf die Finanzkrise................. 14 -

GENERAL ELECTIONS in AUSTRIA 29Th September 2013

GENERAL ELECTIONS IN AUSTRIA 29th September 2013 European Elections monitor The Social Democratic Party’s “grand coalition” re-elected in Austria Corinne Deloy Translated by Helen Levy Like their German neighbours (with whom they share the same satisfactory economic results) the Austrians chose to re-elect their leaders in the general elections on 29th September. Both countries are also due to be governed by grand coalitions rallying the two main political parties – one on the left and the other on the right – during the next legislature. Results As expected the outgoing government coalition formed With 5.8% of the vote (11 seats), the Team Stronach by the Social Democratic Party (SPÖ) of outgoing for Austria, a populist, eurosceptic party founded in Chancellor Werner Faymann and the People’s Party September 2012 by Austro-Canadian businessman (ÖVP) of Vice-Chancellor Michael Spindelegger, came Frank Stronach, will be making its debut in the Natio- out ahead in the election. The SPÖ won 27.1% of the nal Council (Nationalrat), the lower chamber of parlia- vote and 53 seats (five less in comparison with the ment, likewise the Neos-New Austria, a liberal party previous election on 28th September 2008); the ÖVP created on 27th October 2012 by Matthias Strolz, a won 23.8% and 46 seats (- 4). The election illustrates former ÖVP member and supported by the industrialist the continued decline in the electorate of both parties: Hans Peter Haselsteiner, which won 4.8% of the vote together they achieved the lowest score in their his- and 9 seats. tory, mobilizing just half of the electorate (50.9%, i.e. -

Austrian Federalism in Comparative Perspective

CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 24 Bischof, Karlhofer (Eds.), Williamson (Guest Ed.) • 1914: Aus tria-Hungary, the Origins, and the First Year of World War I War of World the Origins, and First Year tria-Hungary, Austrian Federalism in Comparative Perspective Günter Bischof AustrianFerdinand Federalism Karlhofer (Eds.) in Comparative Perspective Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) UNO UNO PRESS innsbruck university press UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Austrian Federalism in ŽŵƉĂƌĂƟǀĞWĞƌƐƉĞĐƟǀĞ Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 24 UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Copyright © 2015 by University of New Orleans Press All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage nd retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, LA 138, 2000 Lakeshore Drive. New Orleans, LA, 70148, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America Book design by Allison Reu and Alex Dimeff Cover photo © Parlamentsdirektion Published in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe University of New Orleans Press by Innsbruck University Press ISBN: 9781608011124 ISBN: 9783902936691 UNO PRESS Publication of this volume has been made possible through generous grants from the the Federal Ministry for Europe, Integration, and Foreign Affairs in Vienna through the Austrian Cultural Forum in New York, as well as the Federal Ministry of Economics, Science, and Research through the Austrian Academic Exchange Service (ÖAAD). The Austrian Marshall Plan Anniversary Foundation in Vienna has been very generous in supporting Center Austria: The Austrian Marshall Plan Center for European Studies at the University of New Orleans and its publications series. -

Austria Aims for Tax Agreement with Liechtenstein by Stefanie Steiner and Christian Wimpissinger

Volume 66, Number 5 April 30, 2012 (C) Tax Analysts 2012. All rights reserved. Tax Analysts does not claim copyright in any public domain or third party content. Austria Aims for Tax Agreement With Liechtenstein by Stefanie Steiner and Christian Wimpissinger Reprinted from Tax Notes Int’l, April 30, 2012, p. 414 Reprinted from Tax Notes Int’l, April 30, 2012, p. 414 COUNTRY (C) Tax Analysts 2012. All rights reserved. Tax Analysts does not claim copyright in any public domain or third party content. DIGEST Austria Aims for Tax Agreement With stein by Austrian taxpayers are held by foundations, which number about 50,000 in a country less than Liechtenstein double the size of Manhattan (160 square kilometers). The Austrian government has announced its inten- Foundations offer a particular feature that appeals to tion to negotiate a bilateral withholding tax agreement some taxpayers: The beneficiaries generally are not with Liechtenstein and to finalize it by the end of identified in public documents. An Austria- April. Liechtenstein agreement that is based on the rationale The Liechtenstein agreement should focus not only of the Swiss agreement but focuses on foundations on bank accounts, but even more, on undeclared invest- would be much more complicated to administer. While ments held in Liechtenstein foundations (stiftungen), the the banking market consists of a specific number of Austrian government said. However, Finance Secretary banks with access to a large number of customers, the Andreas Schieder noted that unlike the negotiations number of foundations, as previously noted, is ex- with Switzerland, talks with Liechtenstein might be tremely high, and each foundation has only a small more cumbersome, both legally and politically. -

Congress of Vienna Program Brochure

We express our deep appreciation to the following sponsors: Carnegie Corporation of New York Isabella Ponta and Werner Ebm Ford Foundation City of Vienna Cultural Department Elbrun and Peter Kimmelman Family Foundation HOST COMMITTEE Chair, Marifé Hernández Co-Chairs, Gustav Ortner & Tassilo Metternich-Sandor Dr. & Mrs. Wolfgang Aulitzky Mrs. Isabella Ponta & Mr. Werner Ebm Mrs. Dorothea von Oswald-Flanigan Mrs. Elisabeth Gürtler Mr. & Mrs. Andreas Grossbauer Mr. & Mrs. Clemens Hellsberg Dr. Agnes Husslein The Honorable Andreas Mailath-Pokorny Mr. & Mrs. Manfred Matzka Mrs. Clarissa Metternich-Sandor Mr. Dominique Meyer DDr. & Mrs. Oliver Rathkolb Mrs. Isabelle Metternich-Sandor Ambassador & Mrs. Ferdinand Trauttmansdorff Mrs. Sunnyi Melles-Wittgenstein CONGRESS OF VIENNA 2015 | 2 Presented by the The CHUMIR FOUNDATION FOR ETHICS IN LEADERSHIP is a non-profit foundation that seeks to foster policies and actions by individuals, organizations and governments that best contribute to a fair, productive and harmonious society. The Foundation works to facilitate open-minded, informed and respectful dialogue among a broad and engaged public and its leaders to arrive at outcomes for a better community. www.chumirethicsfoundation.ca CONGRESS OF VIENNA 2015 | 2 CONGRESS OF VIENNA 2015 | 3 CONGRESS OF VIENNA 2015 | 4 UNDER THE DISTINGUISHED PATRONAGE OF H.E. Heinz Fischer, President of the Republic of Austria HONORARY CO-CHAIRS H.E. Josef Ostermayer Minister of Culture, Media and Constitution H.E. Sebastian Kurz Minister of Foreign Affairs and Integration CHAIR Joel Bell Chairman, Chumir Foundation for Ethics in Leadership CONGRESS SECRETARY Manfred Matzka Director General, Chancellery of Austria CHAIRMAN INTERNATIONAL ADVISORY COUNCIL Oliver Rathkolb HOST Chancellery of the Republic of Austria CONGRESS OF VIENNA 2015 | 4 CONGRESS OF VIENNA 2015 | 5 CONGRESS OF VIENNA 2015 | 6 It is a great honor for Austria and a special pleasure for me that we can host the Congress of Vienna 2015 in the Austrian Federal Chancellery. -

PDF-Dokument

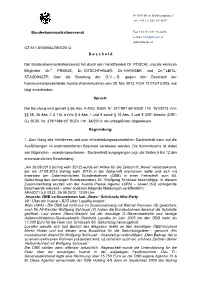

A-1014 Wien, Ballhausplatz 2 Tel. +43 (1) 531 15-4277 Bundeskommunikationssenat Fax +43 (1) 531 15-4285 e-mail: [email protected] www.bks.gv.at GZ 611.810/0004-BKS/2013 B e s c h e i d Der Bundeskommunikationssenat hat durch den Vorsitzenden Dr. PÖSCHL und die weiteren Mitglieder Dr.in PRIMUS, Dr. GITSCHTHALER, Dr. KARASEK und Dr.in LEITL- STAUDINGER über die Berufung der Ö.V. – B. gegen den Bescheid der Kommunikationsbehörde Austria (KommAustria) vom 28. Mai 2013, KOA 12.015/13-005, wie folgt entschieden: Spruch: Die Berufung wird gemäß § 66 Abs. 4 AVG, BGBl. Nr. 51/1991 idF BGBl. I Nr. 161/2013, iVm §§ 35, 36 Abs. 1 Z 1 lit. b iVm § 4 Abs. 1 und 5 sowie § 10 Abs. 4 und 5 ORF-Gesetz (ORF- G), BGBl. Nr. 379/1984 idF BGBl. I Nr. 84/2013, als unbegründet abgewiesen. Begründung: 1. Zum Gang des Verfahrens und zum entscheidungswesentlichen Sachverhalt kann auf die Ausführungen im erstinstanzlichen Bescheid verwiesen werden. Die KommAustria ist dabei von folgendem - unwidersprochenen - Sachverhalt ausgegangen (vgl. die Seiten 5 bis 12 des erstinstanzlichen Bescheides): „Am 26.09.2013 [richtig wohl 2012] wurde ein Artikel für die Zeitschrift „News“ vorab bekannt, der am 27.09.2013 [richtig wohl 2012] in der Zeitschrift erscheinen sollte und sich mit Inseraten der Österreichischen Bundesbahnen (ÖBB) in einer Festschrift zum 60. Geburtstag des damaligen Bundeskanzlers Dr. Wolfgang Schüssel beschäftigte. In diesem Zusammenhang wurden von der Austria Presse Agentur (APA) – soweit [für] vorliegende Beschwerde relevant – unter anderem folgende Meldungen veröffentlicht: APA0271 5 II 0232, 26.09.2012, 12:09 Uhr: „Inserate: ÖBB co-finanzierten laut „News“ Schüssels 60er-Party Utl.: Über ein Inserat - BZÖ über Lopatka empört Wien (APA) - Die ÖBB hat nicht nur im Zusammenhang mit Werner Faymann (S) geworben, auch für Alt-Kanzler Wolfgang Schüssel (V) haben die Bundesbahnen dereinst die Schatulle geöffnet. -

Between Affluence and Influence Examining the Role of Russia and China in Austria

Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies Occasional Paper Between Affluence and Influence Examining the Role of Russia and China in Austria Tessa Szyszkowitz Between Affluence and Influence Examining the Role of Russia and China in Austria Tessa Szyszkowitz RUSI Occasional Paper, July 2020 Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies ii Examining the Role of Russia and China in Austria 189 years of independent thinking on defence and security The Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) is the world’s oldest and the UK’s leading defence and security think tank. Its mission is to inform, influence and enhance public debate on a safer and more stable world. RUSI is a research-led institute, producing independent, practical and innovative analysis to address today’s complex challenges. Since its foundation in 1831, RUSI has relied on its members to support its activities. Together with revenue from research, publications and conferences, RUSI has sustained its political independence for 189 years. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author, and do not reflect the views of RUSI or any other institution. Published in 2020 by the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution – Non-Commercial – No-Derivatives 4.0 International Licence. For more information, see <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/>. RUSI Occasional Paper, July 2020. ISSN 2397-0286 (Online). Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies Whitehall London SW1A 2ET United Kingdom +44 (0)20 7747 2600 www.rusi.org RUSI is a registered charity (No. -

Österreichischer Islamophobiebericht 2018

ÖSTERREICHISCHER ISLAMOPHOBIEBERICHT 2018 FARID HAFEZ BERICHT ÖSTERREICHISCHER ISLAMOPHOBIEBERICHT 2018 COPYRIGHT © 2019 Alle Rechte sind vorbehalten. Alle Rechte dieser Veröffentlichung Gehören der Stiftung SETA - Stiftung für Politik-, Wirtschaft- und Gesellschaftsforschungen (SETA) Kein Teil des Werkes darf in irgendeiner Form ganz oder teilweise elektronisch bzw. mechanisch (durch Fotokopie, Niederschrift, speichern von Informationen oder ein anderes Verfahren) ohne schriftliche Genehmigung von SETA gedruckt, vervielfältigt, veröffentlicht, reproduziert, verbreitet bzw. vertrieben werden. Es darf nur mit Quellenangabe zitiert werden. SETA - Veröffentlichungen 149 I. Druck: Januar 2020 ISBN: 978-625-7040-12-9 Ausführung: Erkan Söğüt Titelbild: shutterstock Druckerei: Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık A.Ş., Istanbul SETA | STIFTUNG FÜR POLITISCHE, WIRTSCHAFTLICHE UND GESELLSCHAFTLICHE FORSCHUNG Nenehatun Cd. No: 66 GOP Çankaya 06700 Ankara TÜRKEI Tel: +90 312 551 21 00 | Fax: +90 312 551 21 90 www.setav.org | [email protected] | @setavakfi SETA | Istanbul Defterdar Mh. Savaklar Cd. Ayvansaray Kavşağı No: 41-43 Eyüpsultan İstanbul TÜRKEI Tel: +90 212 395 11 00 | Fax: +90 212 395 11 11 SETA | Washington D.C. 1025 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 1106 Washington D.C., 20036 USA Tel: 202-223-9885 | Fax: 202-223-6099 www.setadc.org | [email protected] | @setadc SETA | Kairo 21 Fahmi Street Bab al Luq Abdeen Flat No: 19 Kairo ÄGYPTEN Tel: 00202 279 56866 | 00202 279 56985 | @setakahire SETA | Brüssel Avenue des Arts 27, 1000 Brüssel BELGIEN Tel: